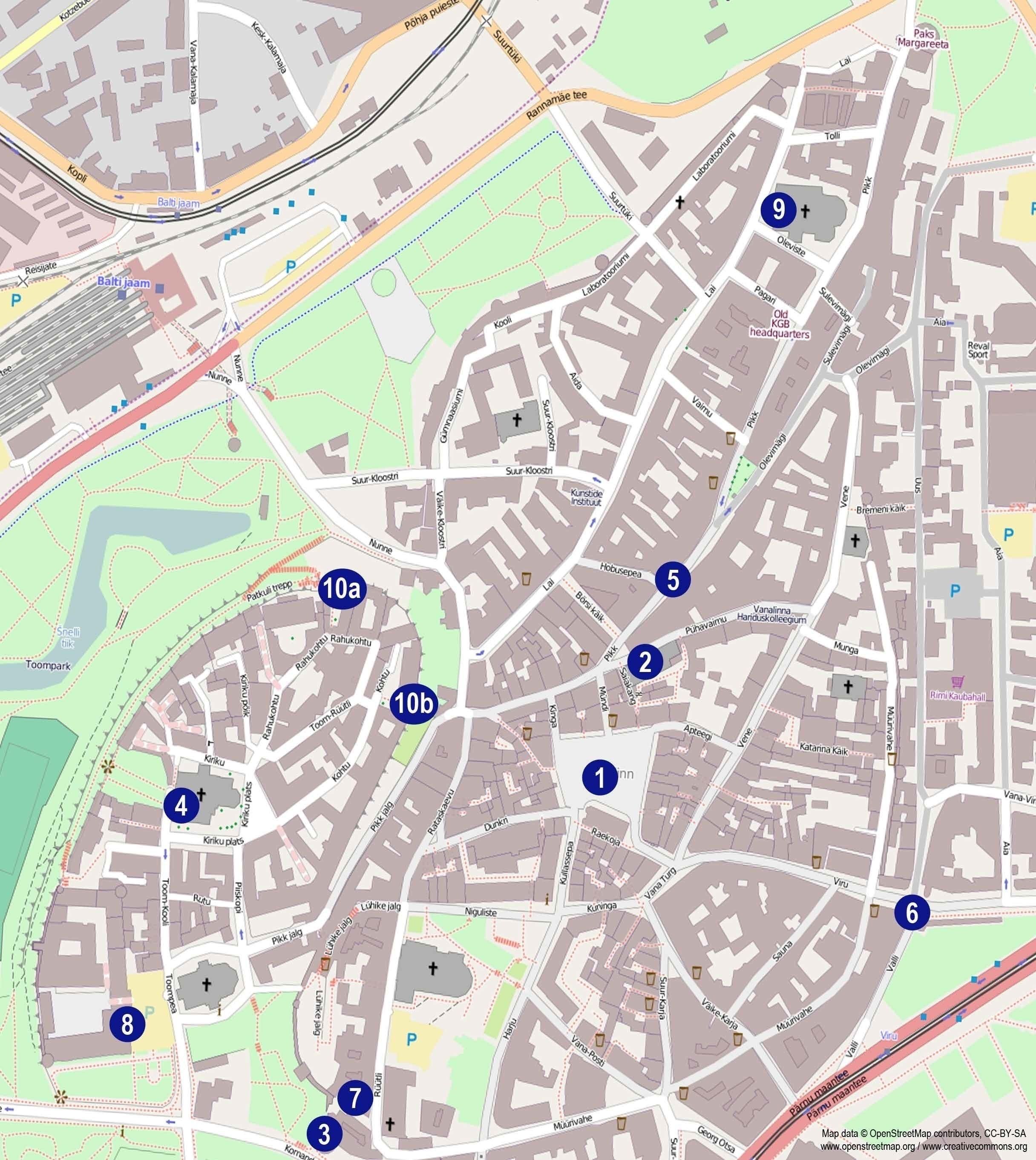

1. Town Hall Square and Pharmacy

2. Holy Ghost Church

3. Kiek in de Kök

4. Dome Church

5. Medieval Guild Houses

6. Viru Gates

7. Executioner’s House

8. Toompea Castle

9. St. Olaf’s Church

10. Viewing Platforms of Toompea

History of Tallinn

Christmas and New Year’s Eve

Flag, Coat of Arms, and Anthem of Estonia

Estonian Humor and Jokes

Welcome to the WanderStories™ tour of the top 10 sights in Tallinn. We are now ready to take you on your personal tour.

We will also tell you the brief history of Tallinn and several additional stories about the national symbols of Estonia, Estonian cuisine, holidays, even jokes.

We, at WanderStories™, are storytellers. We don’t tell you where to eat or sleep, we don’t intend to replace a typical travel reference guide. Our mission is to be the best local guide that you would wish to have by your side when visiting the sights. So, we meet you at the sight and take you on a tour.

WanderStories™ travel guides are unique because our storytelling style puts you alongside the best local guide who tells you fascinating stories and unusual facts recreating the passion and sacrifice that forged the beauty of these places right here in front of you, while a wealth of high quality photos, historic pictures, and illustrations brings your tour vividly to life.

Our promise:

• when you visit these top sights in Tallinn with this travel guide you will have the best local guide at your fingertips

• when you read this travel guide in the comfort of your armchair you will feel as if you are actually visiting these top sights in Tallinn with the best local guide

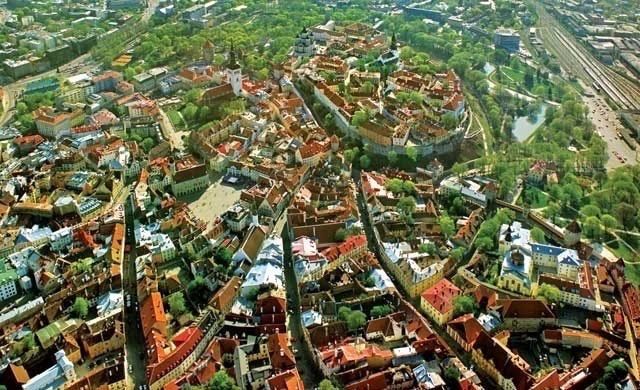

The historical center (Old Town) of Tallinn is in the UNESCO World Heritage List. There is only one thing to do now – visit!

Let’s go!

Your guide, WanderStories

Once you have read this book please review it, we truly appreciate your feedback.

Please subscribe to the FREE WanderStories™ travel e-magazine, Armchair Travel Guide at: wanderstories.com/travel-magazine

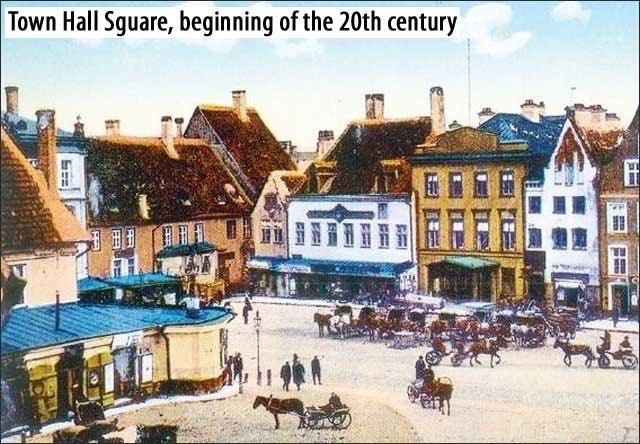

Town Hall Square and Pharmacy (No. 1 on the map)

Address: Raekoja plats

59°26'15.3"N 24°44'43.7"E

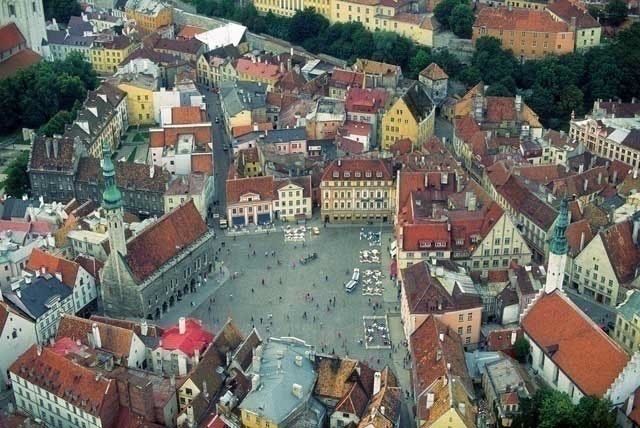

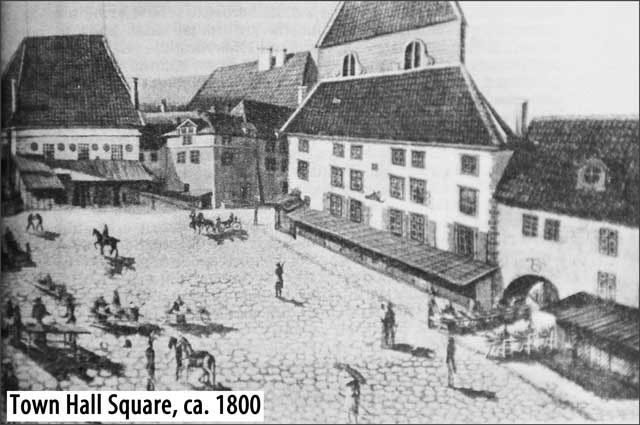

Town Hall Square has remained the heart of Tallinn for over 800 years.

As trading increased in importance in the 13th century, more houses, storehouses and shops were built.

A market was set up and continued in the square until 1896. It got its current name – Town Hall Square, only in 1923.

Already in the 13th century the square was full of daily hustle and bustle with shoemakers on the west side and street stalls selling different items.

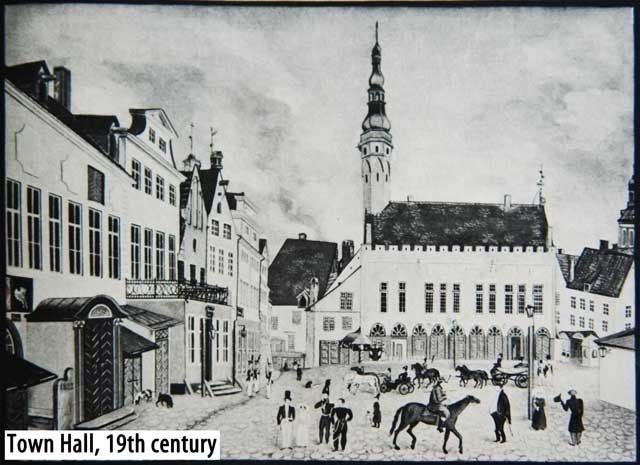

On the south side of the square is the Town Hall, which used to be the most important building in the whole of Tallinn.

This 700-year-old building is the only medieval town hall in the whole of the Baltic region and is one of only a handful in Europe dating back to the 14th century.

The development of town halls is closely linked with trade. This can be seen in the covered arcade of Tallinn’s own Town Hall, which was constructed to allow trading to continue even in bad weather.

For most of its history, the Town Hall has acted as the judicial and administrative center for the town. It is not known when exactly the first Town Hall building was erected, but it was first mentioned in written documents in 1322. Since then, there have been changes and additions and by the end of the 14th century, it was more or less as you see it today.

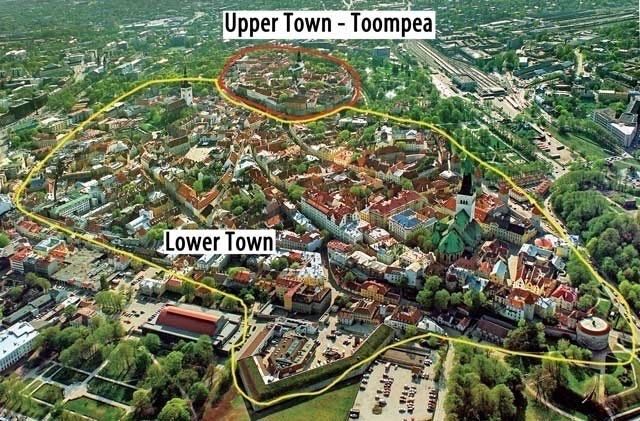

Tallinn’s Town Council resided in the Town Hall building until 1970. Although Estonia was governed from Toompea (the Upper Town of Tallinn), Tallinn’s subordination to Toompea was more formal than real.

In 1433, a major fire destroyed nearly the entire town, although miraculously, the Town Hall was preserved, even though it had a wooden roof.

In 1780, the building again survived when lightning struck the roof, went through a window of the assembly room and out another. Unfortunately, another bolt of lightning hit the guardroom, killing a guard there instantly.

Look up to the very top of the spire and you can see an impressive weathervane called Old Toomas (Vana Toomas), named after a legendary town guard. He had first come to prominence when, while still a young lad, he had proved to be a crack shot with a bow at the annual parrot-shooting contest. The parrots were wooden, not live ones!

The original weathervane, dating back to 1530, was destroyed in a 1944 air raid.

The magnificent dragon head waterspouts were added to the facade in 1627.

The interior is well worth a visit, both for its contents and its architecture. You may even be lucky enough to attend a concert here.

Several famous historical characters have been received here, including: the Swedish King Gustaf Adolf, and from Russia, Tsar Peter the Great, Empress Catherine II, and Tsar Nicholas II.

The Town Council has always taken care of law and order in Tallinn. During the Middle Ages, there were town laws forbidding unreasonable luxury and splendor, particularly when it came to weddings, christenings and funerals. We’re not sure if this was because of envy, jealousy, modesty, or something else.

In 1324, the Town Council ordered that wedding guests were to be limited to no more than 60. Those who broke the law had to pay a fine of three silver marks to support the building of the town wall. With this money one could have bought two strong horses.

Only 12 ladies were allowed to take part in a baby shower. The fine for neglecting this was one silver mark.

The Town Council also dictated the dress code. What one could wear depended on one’s rank and social class. To break the rules meant huge fines.

In 1650, the rules were not correctly followed at the wedding of Bernhard Hetling’s daughter, Anna. The bridal couple wore too fancy wedding clothes. As the groom was a wine merchant, four different kinds of wine were served. The fine for all this luxury was huge, plus the wedding clothes were confiscated.

Regardless of these rules, the funerals of blue-blooded noblemen were always spiced with luxury and riches. The magnificent funeral parade was followed by a demonstration of the dead man’s weapons. His favorite horse followed behind the coffin. The horse followed even into the church to the funeral service. During the ceremony, cannons were fired and church bells rang.

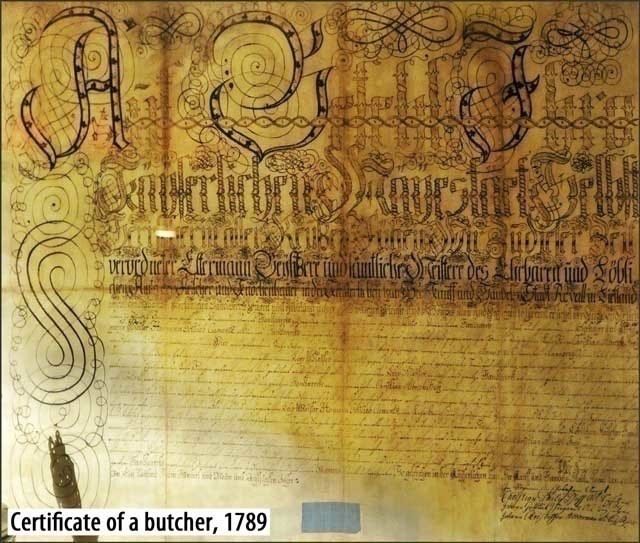

The Town Council enforced laws covering merchants and trades people. For example, butchers were only allowed to sell good quality fresh meat. If it was sub-standard in any way, it was confiscated and sent to the poor of the town.

If you wanted to check that you hadn’t been cheated, you could take the length of cloth that you’d bought and measure it by the instrument attached to the Town Hall wall.

Fixed price laws were enforced by the Town Council. Any craftsman who asked too much for his wares had to pay a fine – 3 times the official price of the product.

There were also restrictions on masters from other towns, who were not allowed to sell products which were already being produced by local craftsmen. It was believed that this protected local masters, such as tailors, tin casters, or shoemakers from becoming destitute.

The only people who were allowed to trade in the town of Tallinn were the ones with a vocational certificate. Those without, so-called guild rabbits, could not trade at all. They were punished if they broke these rules.

So you can see that consumer protection was well-organized here. Anyone who disobeyed the trading laws could expect to be punished. Forgers usually had to pay a fine, a relatively mild punishment. However, poor quality work was considered a serious crime in Tallinn and those considered guilty were cast out of town.

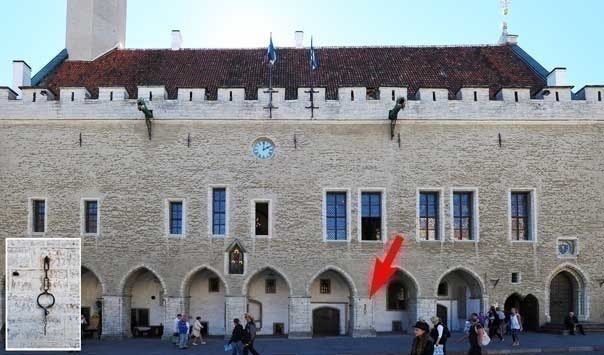

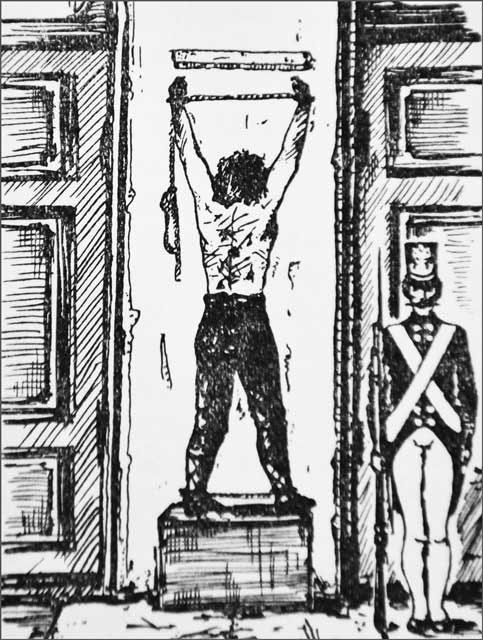

You can see an iron collar attached to one of the columns of the Town Hall building.

Those guilty of petty crimes were punished here.

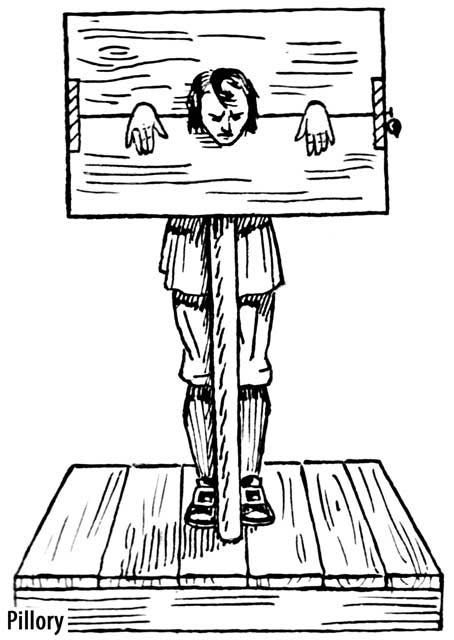

In the center of the square, a pillory stood until the end of the 1820s.

A large carved stone once marked the spot where it was located.

People suffered on the pillory for a variety of crimes. As trade was such a vital part of life, many crimes related to trade, such as selling poor quality goods, warranted the pillory. A wooden statue of a man holding a rod, placed on top of the pillory, was a constant reminder to the merchants trading here.

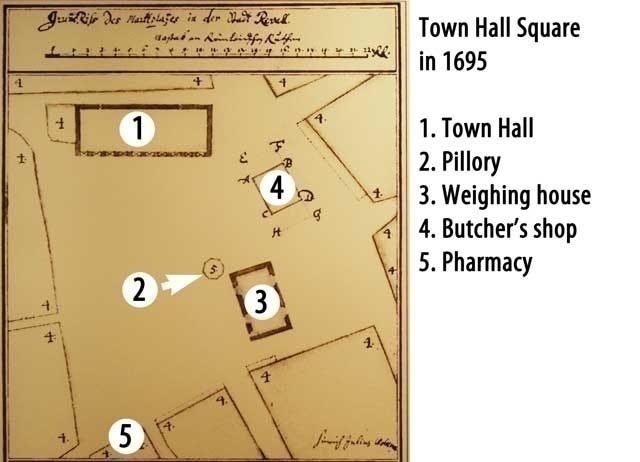

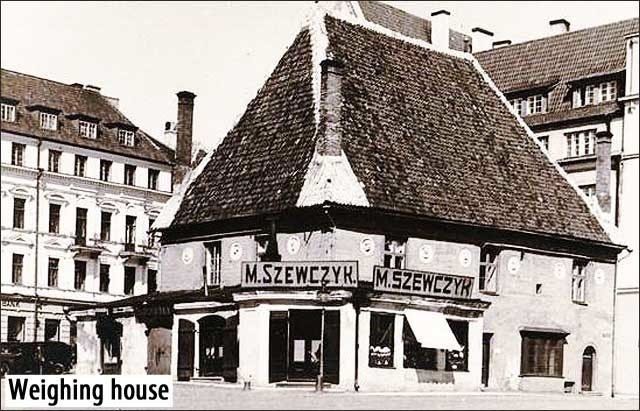

Directly opposite the Town Hall, there was a 14th century weighing house.

There, until the middle of the 17th century, imported and exported goods were weighed and measured. Unfortunately, it was destroyed in 1944 during the war.

A foundry was also based in the square before being removed to Rataskaevu Street in the 15th century. All sorts of metal items were made there, including church bells for Tallinn and elsewhere.

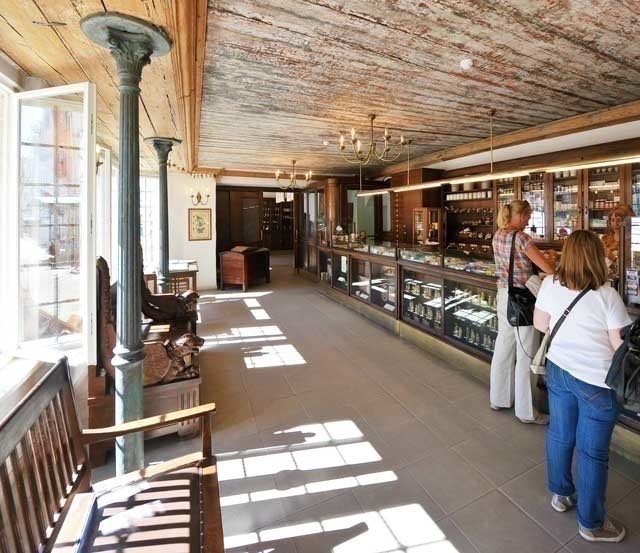

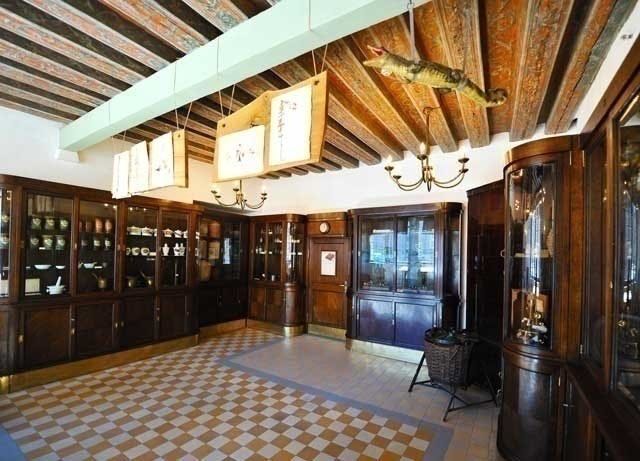

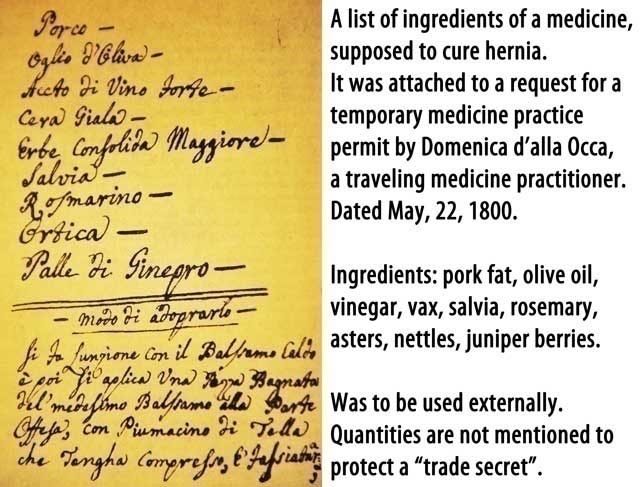

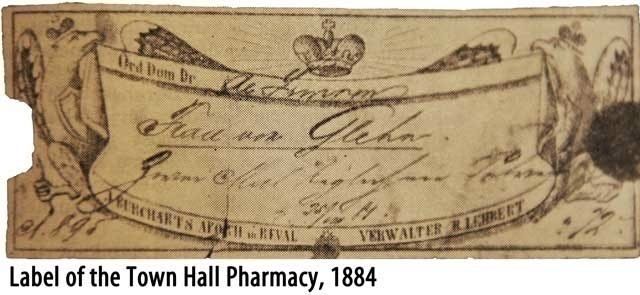

On the north side of the square is the Town Hall Pharmacy. This pharmacy is one of the oldest in Europe to maintain its original function. It was first mentioned in written documents in 1422, although it is believed to be even older.

The present facade of the building dates from the 17th century.

At the end of the 16th century, there were no doctors at all in Tallinn so sick people had to rely on the pharmacists. In 1710, when plague killed very many people, these pharmacists were overwhelmed with patients.

In 1689, Johan Burchart bought the building from the Town Council for a vast sum.

His coat of arms can be seen in the far room of the present day pharmacy.

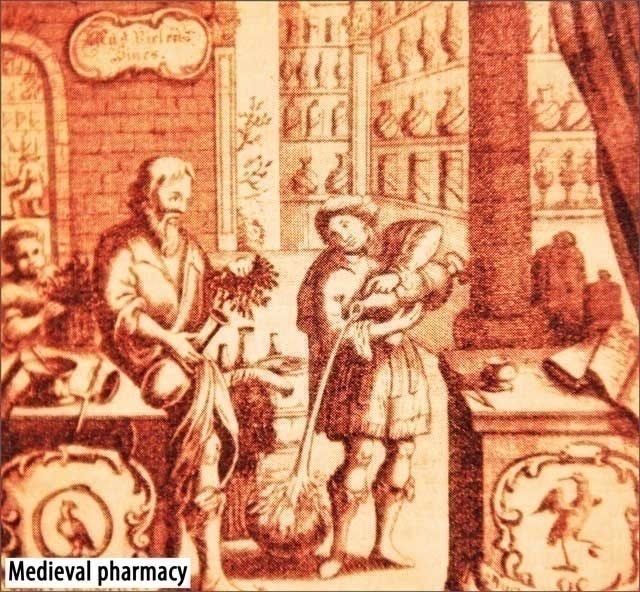

During the Middle Ages, one could get an assortment of medicines from the pharmacy to cure a variety of ailments.

On sale were the following: powdered unicorn horn, pike eyes, pieces of mummy from faraway Egypt, dog excrement bleached white, spirit of urine, skull salt, the blood of a billy-goat, the fat of a snake, dried toads, burned bees, angleworm oil, stallion hooves, scorched hedgehogs, and deer penis.

It was also believed that color was important in curing an illness. So the following precious stones, matched to the color of the illness, would be prescribed: yellow beryl for jaundice, sapphire for plague sores, and purple amethyst to get rid of alcoholism.

Spices were not only sold to cure illness, but also to add taste to bland foods and to disguise the bad taste of wine. The pharmacy even sold its own brand of klarett (claret), made from Rhenish wine with added spices.

Aqua vitae or vodka was also on sale. When it comes to vodka, the Estonians have a saying: “If you don’t have a fatal disease, you can always turn to vodka for help!”

There are other old buildings to note in Town Hall Square, such as the house at No. 13, which was built in the 15th century when the Town Council ordered all wooden buildings to be rebuilt in stone because of the fire risk.

No. 12, to the left, has been preserved as one of the oldest craftsman’s dwellings in the town. In the 14th century, this corner shop was owned by a fur dealer.

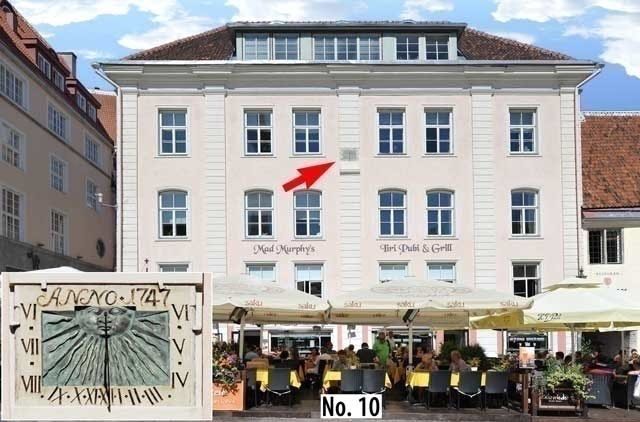

No. 10 is significant for the sundial attached to the facade, while No. 15 used to house the office of the Town Council.

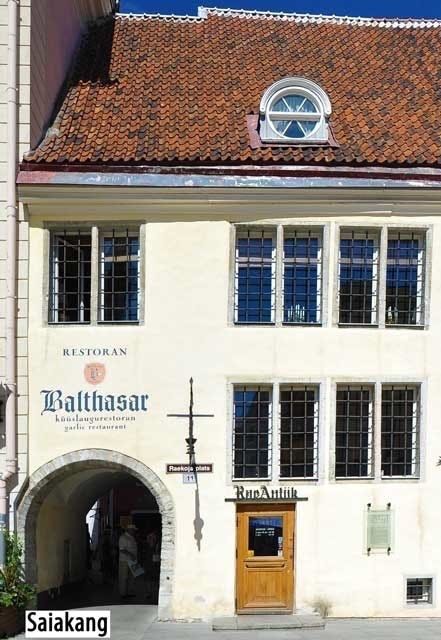

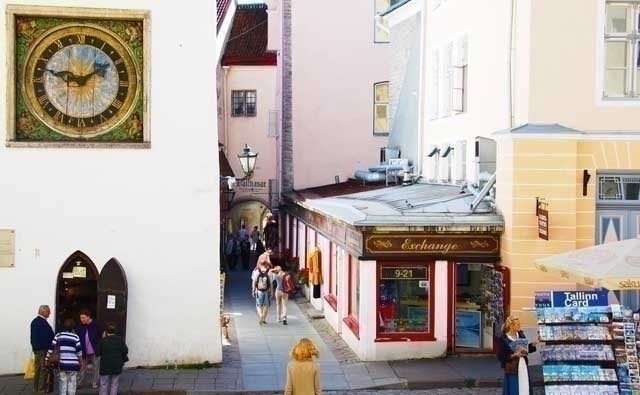

Town Hall Square is connected to Pikk Street by a short, narrow pedestrian lane called Saiakang. If you’re hungry, you can sit down in a cafe here and have a cup of coffee and a yummy pastry. If you came 600 years ago, you could have bought bread here.

This street has had several names in different languages: in Estonian, its name can be translated as bread passage or bread archway. In German it was Weckengang; in Russian, Bulotshnoi Rjad or Hlebnoi Pereulok. All these names are connected with bread and describe how narrow the lane is.

Saiakang is one of the oldest streets in Tallinn and existed in the far-gone era when Tallinn was called Kalevinlinna or Kolõvan back in the 14th century.

It’s been used for centuries by pedestrians. A rotating barrier facing Pikk Street was set up to prevent vehicle access. The other end, leading into Town Hall Square, was left unblocked so that shops and businesses could be re-supplied.

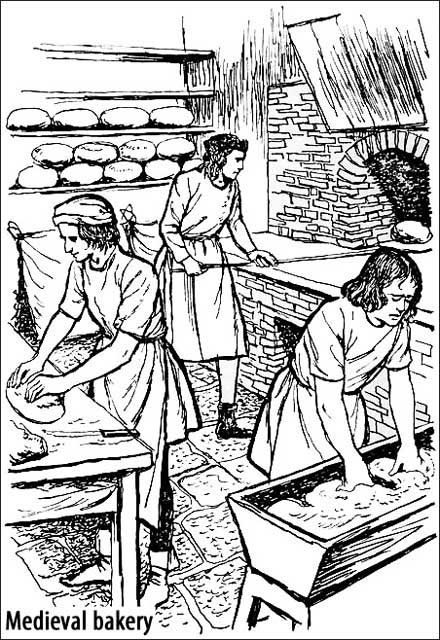

Why bread passage? It was recorded in 1374 that there were eight shops altogether selling bread here.

Amongst others, a special kind of bread, called timp bread, was sold here. This was a small square loaf with four horns and was made out of cooked dough. It probably originates from the town of Enger in Germany, where it was the custom for children to hand out timp bread during the Feast of Epiphany. It’s also mentioned in Estonian folklore and literature, and is still used in everyday speech. For example, if someone is tired of the long ride to town, they can be cheered up by others with the saying, “The horns of the town bread are already in sight!”

Originally, the bread passage shops were made of wood. By the end of the 17th century, these had been replaced with stone. They were for rent only to Tallinn citizens, who could rent just one shop. Curiously, these shops were rented on a rotational basis, because some were better located than others, so that everyone could earn an equal profit.

Those who rented were usually older women from the common folk. As the old German saying puts it, “She prattles like an old woman from bread passage.”

In the 15th century, three timp bread loaves cost one pfennig. At this time, from his daily salary, an apprentice of a master could purchase twelve timp loaves and a simple carpenter, ten.

Bakers had to use good quality flour to bake bread. The different kinds of bread had their own specific weight and had to be marked with the personal sign of the master baker.

From time to time, the guild masters of the Bakers Guild came from the Town Hall to inspect the timp bread. These couldn’t be burned or moldy. The flour had to be pure with no worms in it. Poor quality baking was not sold but cut into pieces and sent to the St. James Almshouse lepers.

After 1896, the shops were sold and rebuilt into two bigger stores. At the present No. 3, there used to be three shops and at No. 5, five shops during the Middle Ages.

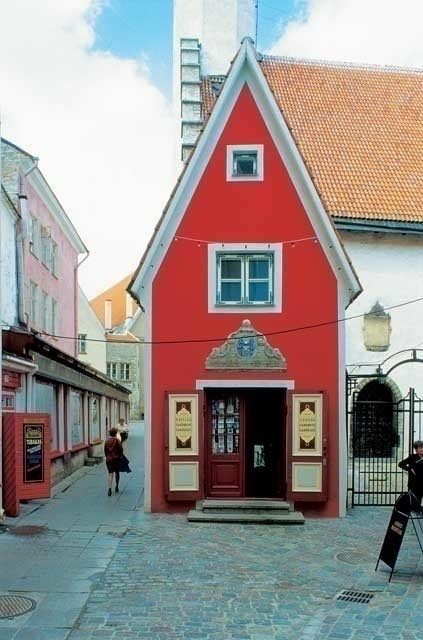

Land for building on the corner of Saiakang and Pühavaimu Street was always very valuable and several important merchants and personages wanted this land. Finally, Burgomaster Berhard Hetling, by means of subterfuge, was able to purchase the land. After the deal, Hetling built a small stone house there, which you can still see next door to the church.

Certain activities were considered not suitable for the area, so no inns or pubs were permitted, as was anything to do with alcohol.

This may now be the ideal opportunity to sample bread passage wares, just as people did hundreds of years ago.

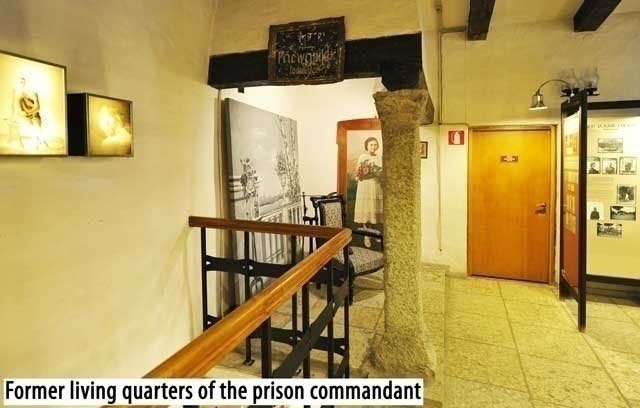

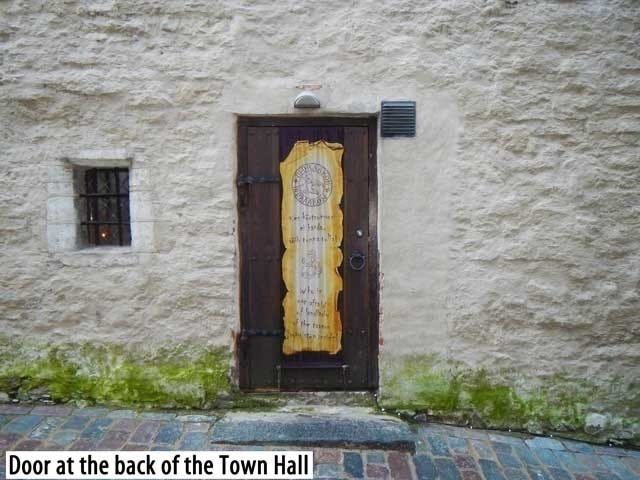

Town Council’s Prison, at Raekoja Street 4/6, is behind the Town Hall. At the end of the 17th and the beginning of the 18th centuries, this street was also called by a name which can be translated as Parsley Street, because the street’s residents used to keep their vegetables in the cellars. But this is not the reason why the street is so well-known.

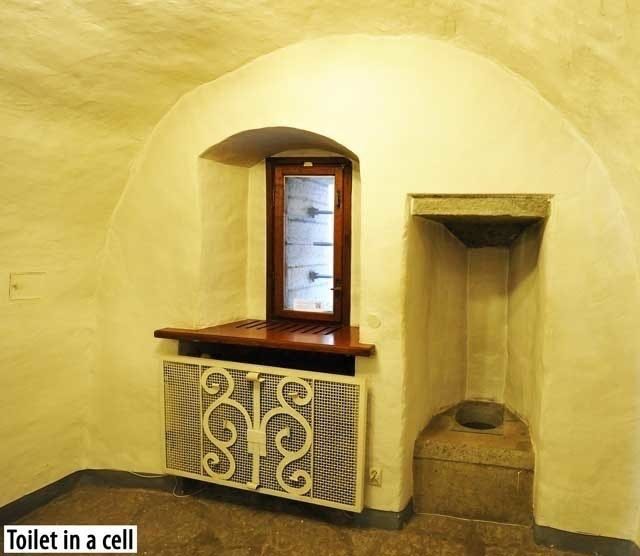

From the Middle Ages up to the beginning of the 19th century, No. 6 housed the town’s lockup and the living quarters for the prison commandant.

This house has been called by several names: the torturer’s house, the judge’s house, and the common people’s lockup. For a short time, it was used to imprison poor people who had been arrested for petty crimes. On the other hand, rich citizens were detained at the Weighing House in Town Hall Square.

For more serious crimes, people could be locked up in the bakery cellars of Saiakang, in Marstall at Rüütli Street, or at the town wall towers at Müürivahe, Laboratooriumi and Vene Streets.

During the 14th century, the lockup was once used to detain people arrested for vandalizing the building and verbally abusing the prison guard’s helper’s wife.

Any common person found walking outside after the 9 p.m. curfew could be locked up too.

Craftsmen and apprentices could also end up there for dishonoring their guild by getting drunk at their workplace. As punishment, they were locked up for three days, getting only bread and water. Fighting and injuring someone could lead to a spell in the clink as well.

The vaulted rooms here were used as prison cells. The most serious offenders, while awaiting the verdict of the Town Council court, were chained to an iron collar fastened to the wall.

To facilitate the court process, a door was built at the back of the Town Hall to give easier access.

This door led to the Town Hall torture chamber and from there, to the hall used when the court was in session.

For a while, this street was fenced off to citizens who had been fouling it using human waste. One can only guess that this improper behavior was due to hatred toward the executioner’s helper, who had his residence in the same street. A gate at the end of the street was locked at night. In the middle of the 18th century, one executioner’s assistant built some pigpens in the street, which were used for over 20 years before being pulled down. After this, the street again became open to everyone.

For 800 years, Town Hall Square has been a focal point for important festivals and ceremonies.

With the celebration of St. John’s Day on June 24, a two-week annual fair began with a colorful flag-waving procession led by aldermen (members of the Town Council) accompanied by the rattle of drums and the blare of horns.

It’s still the same today, with concerts, a Christmas market and special events such as welcoming the winners of the Olympic Games home. Queen Elizabeth II of Great Britain was also entertained here with a music concert in 2006.

So, stand in the square and drink in all this history!

To many, Estonia is just a blank spot on the map of European cuisine, compared to say, Swedish meatballs, Norwegian salmon and Italian pizza, not to mention the French cuisine. One recent slogan calls Estonian food simple and tasty.

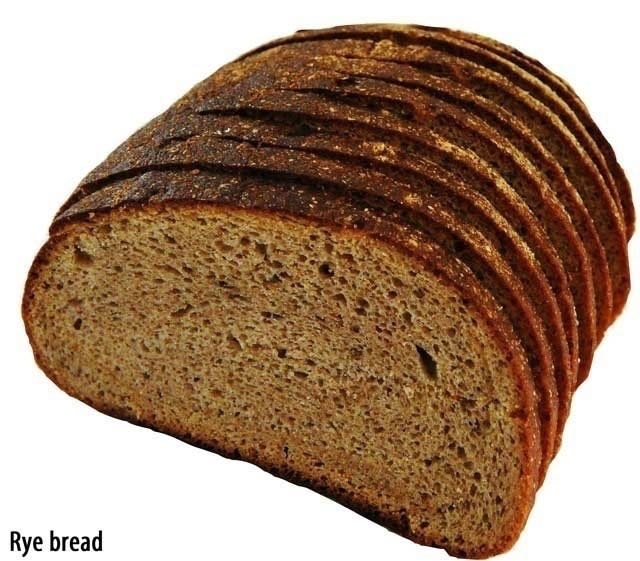

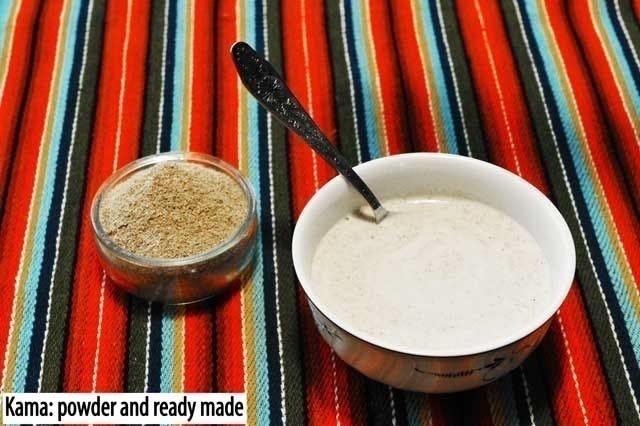

The question, what is real Estonian grub, has been hotly debated. There are several recipes that could be considered as national food: boiled pork with vegetables, grain porridge with potatoes and bacon, oven-roasted pork with sauerkraut, blood pudding and dark barley bread. There is also a dish called kama, made of flour consisting of rye, oats, barley, and pea-meal with added fermented milk (kefir) and sugar to taste. Some of these recipes are ancient, while some are comparatively new, and others have been adapted from foreign sources. Estonian cooking is greatly influenced by German and Russian cuisines.

The food here is similar to that found in other northern European countries – hearty peasant fare that helps to cope with hard physical labor and harsh weather conditions.

Whatever could be eaten was. During the Middle Ages, Estonians were omnivorous, just like the bear, still found in large numbers in the dense forests of Estonia.

Although we don’t know much about ancient times, barley was an important nutrient. It was nutritious and cheap and was used to make porridge and gruel, as well as a good quality beer. Some rye was also produced and was the main grain for bread. Estonian peasants also ate peas, beans, and lentils. Meat came from cows, pigs, horses and game, if it could be caught.

Obviously, the richer you were, the better you ate. It also depended on whether you lived in the town or the country. A poor man’s staple diet was porridge or gruel.

A special dark rye bread, found only in Estonia (to some extent also in neighboring Latvia), is still highly valued. If someone is eating, it is polite to say, “May you have plenty of bread!” or jätku leiba in Estonian, which is basically the same as bon appetit. It doesn’t matter if one is eating a banana or caviar, it’s still polite to say this. If you happen to drop a piece of bread, you must pick it up and give it a kiss.

Meat was rarely present on a peasant’s table. Animals were butchered in autumn and the meat was either smoked or salted to preserve it through the winter months. Out of a pig’s head and its legs, a veritable feast was prepared. This is still eaten on Shrove Tuesday. A pea and bean soup was also served with pork. Sausages too, made a great holiday fare. Two kinds of special ones were served: white pudding, made of grain with a bit of meat added to it, and blood sausage. The latter is still a popular dish at Christmas time.

As Estonia borders the sea, there is never a lack of fish. Mainly small salted herrings.

For vegetables, Estonians ate cabbages and turnips. Cabbage was eaten fresh. The first sauerkraut was only prepared here from the 19th century. Turnips were baked under the ashes of a fire. Even though Estonia is known as the Potato Republic, for Estonian farmers grow a lot of potatoes, this vegetable wasn’t known here until the end of the 19th century. Since then, potatoes have become a staple for Estonians.

Sour milk, beer, and light ale were regular drinks for the common people.

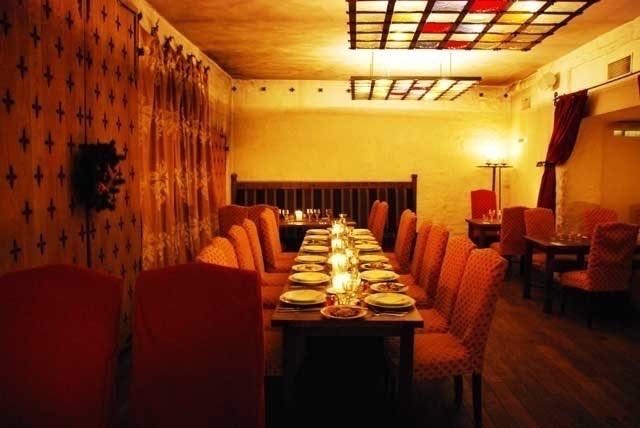

Bread was the main course for the poor man, while the Tallinn citizen ate bread with other foodstuffs. The townsfolk liked all kinds of meat – mutton, goat, pork, beef, veal, and poultry. Game and cheese were considered gourmet fare. On feast days, the tables groaned with rich food. Luxury foods included fish in jelly and dishes dyed with various pigments. There always had to be a surprise dish, such as swan or peacock. Firstly, the skin and feathers were removed, the bird was fried and then put back in its skin. The feathers were dyed golden and decorated. Leftovers were distributed to the poor.

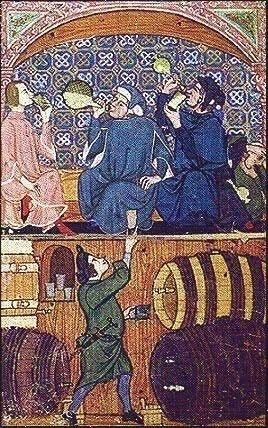

But, it seemed that a full stomach was not as important as a thick head, caused by being drunk. Wine and beer flowed like rivers in medieval Tallinn. There were very expensive southern wines, also the spiced ones with honey and seasonings. The most beloved fortified wine was klarett (claret). It tasted good and it definitely made you tipsy.

Oceans of beer were consumed during major celebrations. For instance, in the middle of the 16th century, 300 liters (80 gallons) of beer were drunk in the Great Guild every day, and during the May Count festivities, 1,700 liters (450 gallons) of beer and wine were quaffed.

What we now consider to be the national food of Estonia originated mainly in the middle of the 19th century and formed part of the peasants’ table. At this time, porridge and soup were made of grain harvested in the fields. Porridge still forms part of our breakfast.

Kama is a unique Estonian dish. It’s made of a flour consisting of rye, oats, barley, and pea-meal, which is boiled, dried, and ground. Originally, it was mixed with sour milk, although today, fermented milk (kefir) or yogurt is more commonly used. You can add salt or sugar to taste. This comes highly recommended and you can buy it from almost any grocery store in Tallinn.

Estonian eating habits have been developed over the centuries, with outside influences playing their part. The modern Estonian gladly eats potato salad, liver pate, pancakes, meat dumplings, and borshch, the thick Russian beetroot soup. Fortunately, along with foreign food, Estonians still like their own native dishes.

Is the talk of food making you hungry? If so, no problem. Tallinn has many fine restaurants serving food ranging from gourmet to honest, everyday grub. Find yourself somewhere, outdoors (only during summer) or indoors, settle down and…jätku leiba!

1. Town Hall Square and Pharmacy

2. Holy Ghost Church

3. Kiek in de Kök

4. Dome Church

5. Medieval Guild Houses

6. Viru Gates

7. Executioner’s House

8. Toompea Castle

9. St. Olaf’s Church

10. Viewing Platforms of Toompea

10a. Patkuli Piewing Platform

10b. Kohtuotsa Viewing Platform

Travel guides that show you around and tell stories, not just history.

Dear Traveler, please review this book, we truly appreciate your feedback.

Are you exploring famous landmarks in cities around the world? Are you looking for more insight than a typical guidebook provides you? Perhaps you would like your own personal tour guide but prefer to visit places at your own pace? Are you curious about how people lived in those palaces and castles? Maybe you just want to understand people from different cultures better? Well, we have exactly what you need, we tell WanderStories™.

WanderStories™ is the best local guide for you, showing you around and telling stories of famous and interesting sights, in an e-book on your tablet, smartphone, or computer.

WanderStories™ travel guides are unique because our storytelling style puts you alongside the best local guide who tells you fascinating stories, while a wealth of high quality photos, historic pictures, and illustrations brings your tour vividly to life.

WanderStories™ travel guides are e-books that include lots of photos, maps, and illustrations and tell you the stories behind the history of the places you will visit, like the best personal tour guides would do. In fact, they do it so well that you can visit the most extraordinary places around the world without even leaving the comfort of your armchair. Wherever you are, you can experience the excitement of history being recreated around you as the story unfolds.

You will get to know how real people, emperors and sultans, concubines and eunuchs, slaves and executioners, lived in the palaces you will visit; what gods the monks worshipped in these temples; how generals and soldiers, crusaders and gladiators fought and won…or died. You will learn about local traditions and customs, holidays and festivals, cuisine, even jokes.

Whether you’re at home, on your travels, or walking in the historic setting itself, WanderStories™ is the best personal, local guide on your tablet, smartphone, laptop, or computer.

We, at WanderStories™, are storytellers. Our mission is to be the best local guide that you would wish to have by your side when visiting the sights.

Our promise:

• when you visit a city with a WanderStories™ travel guide you will have the best local guide at your fingertips

• when you read a WanderStories™ travel guide in the comfort of your armchair you will feel as if you are actually visiting the best sights in the city with the best local guide

Please get WanderStories™ travel guides at: wanderstories.com

Please subscribe to the FREE WanderStories™ travel e-magazine, Armchair Travel Guide at: wanderstories.com/travel-magazine

Tallinn audio guide is available at: audioguideworld.com

Sample from: Tallinn Stories Top 10

Copyright © 2014 WanderStories

Photos and illustrations provided by WanderPhotos™, exceptions are as follows:

Flickr user jurvetson is the author of the following photo:

All of the following photos are courtesy of Tallinn City Tourist Office & Convention Bureau:

Allan Alajaan is the author of the following photos:

Arne Maasik is the author of the following photos:

Toomas Volmer is the author of the following photos:

Ain Avik is the author of the following photos:

Maret Põldveer is the author of the following photos:

Kirsti Eerik is the author of the following photos:

Marko Leppik is the author of the following photos:

Jaak Nilson is the author of the following photos:

Sheila Barry is the author of the following photos:

Jüri Seljamaa is the author of the following photos:

Karel Koplimets is the author of the following photos:

Kaido Haagen is the author of the following photos:

Toomas Tuul is the author of the following photos:

Author unknown:

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or distributed in any form by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems without permission in writing from the publisher.

Disclaimer. Although the authors and publisher have made every effort to provide up-to-date and accurate information, and have taken all reasonable care in preparing these publications, they accept no responsibility for loss, injury or inconvenience sustained by any person relying on or using our publications, and make no warranty about the accuracy or completeness of their content and, to the maximum extent permitted, disclaim all liability arising from their use.