St. Peter’s Basilica

Vatican Museums

Roman Forum

Pantheon

Castel Sant’Angelo

Trevi Fountain

Capitoline Museums

Piazza Navona

Villa Farnesina

History of Rome

Italian Cuisine

Italian Traditions and Customs

Italian Holidays and Celebrations

Italian Jokes and Humor

What Makes Italians Italian

Welcome to the WanderStories™ tour of the top 10 sights in Rome: St. Peter’s Basilica, the Vatican Museums, the Colosseum, the Roman Forum, the Pantheon, the Castel Sant’Angelo, the Trevi Fountain, the Capitoline Museums, Piazza Navona, and the Villa Farnesina. We are now ready to take you on your personal tour of these world famous landmarks.

We will also tell you the history of Rome and several additional stories about Italian cuisine, traditions and customs, holidays and celebrations, humor and jokes, and what makes Italians Italian.

We, at WanderStories™, are storytellers. We don’t tell you where to eat or sleep, we don’t intend to replace a typical travel reference guide. Our mission is to be the best local guide that you would wish to have by your side when visiting the sights. So, we meet you at the sight and take you on a tour.

WanderStories™ travel guides are unique because our storytelling style puts you alongside the best local guide who tells you fascinating stories and unusual facts recreating the passion and sacrifice that forged the beauty of these places right here in front of you, while a wealth of high quality photos, historic pictures, and illustrations brings your tour vividly to life.

Our promise:

• when you visit these top 10 sights in Rome with this travel guide you will have the best local guide at your fingertips

• when you read this travel guide in the comfort of your armchair you will feel as if you are actually visiting these top 10 sights in Rome with the best local guide

Welcome to Rome – the Eternal City, which was according to legend founded in 753 B.C.E. by two twin brothers – Romulus and Remus.

The history of Rome is that of wars and struggles for power, of magnificent buildings and feats of engineering. Some sights that you see today are well over two thousand years old and yet they are still standing, bringing the magnificent history of the city’s past to life.

Throughout its long history Rome has always been a center of power, culture, and religion. Today, it has an immensely rich historical heritage and cosmopolitan atmosphere, making it one of Europe’s most visited, famous, influential, and beautiful capital cities.

The historic center of Rome is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

There is only one thing to do now – visit!

Let’s go!

Your guide, WanderStories

Once you have read this book please review it, we truly appreciate your feedback.

Please subscribe to the FREE WanderStories™ travel e-magazine, Armchair Travel Guide at: wanderstories.com/travel-magazine

Colosseum

Address: Colosseo, Piazza del Colosseo

41°53'24.8"N 12°29'32.1"E

The enormous arena of the Colosseum is the largest remaining symbol of imperial Rome still in existence today.

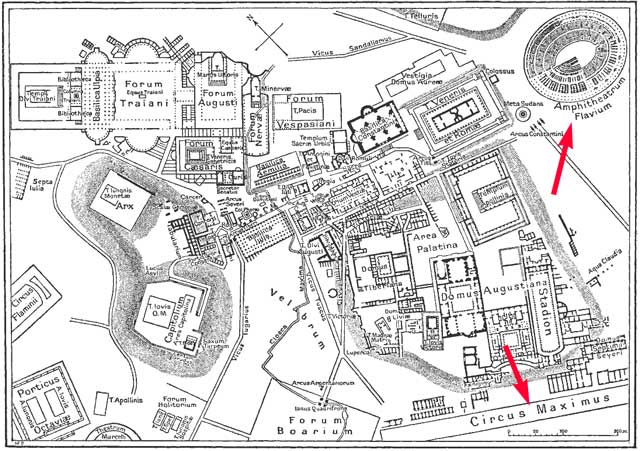

It is situated to the east of the Roman Forum.

On the other sides, across the busy city traffic, it is surrounded by the Esquiline, Caelian, and Palatine hills.

Once a place for triumphs, games, and executions, the arena was a display of wealth and strength on a gigantic scale.

Today, the four-story structure is only a glimpse of its former glory.

Although the marble facings, beautifully painted stucco walls, and elegant statues have been taken to enhance other buildings throughout the city, enough of the original amphitheater still remains to help create an image of what it was like at the height of the Roman Empire.

The best view of the Colosseum is from the northwest, where you have a good perspective of the scale with the four floors still visible.

Let’s walk around the outside past the Arch of Constantine and enter via the main entrance in the west.

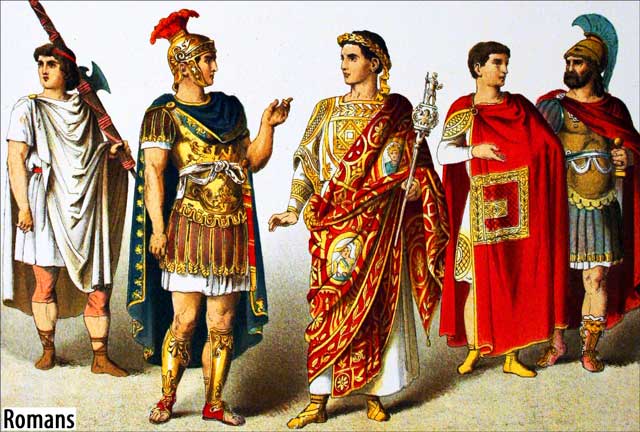

This is the way plebeians – the ordinary Roman citizens, would have entered the grand Colosseum, lavishly decorated with statues of horses, eagles – which signified the power of Rome – and ancient gods such as Hercules and Apollo.

They would enter through one of 76 entrances, the entrance number was indicated on their ticket.

Each doorway was clearly numbered to allow thousands of people to enter in an orderly manner.

The tickets were in the form of small clay discs which were stamped with details of the locus – the seat number, gradus – the row number, and cuneus – the sector number. For example: LOC X – meaning seat number 10, GRAD V – row number 5, CVN III – sector number 3.

Tickets were free, but everyone had to have a ticket to attend. Tickets were distributed to organizations, institutions and groups, who in turn distributed them to the Roman citizens. As the games were popular, there was also a black market, where tickets would be sold, with high prices for some of the most important games.

There were also four other entrances. Two were for the gladiators – Porta Sanivivaria, the Gate of Life, which led to their barracks and Libitina, the Gate of Death, the gate where corpses and the defeated, badly injured, but still living, left the grounds.

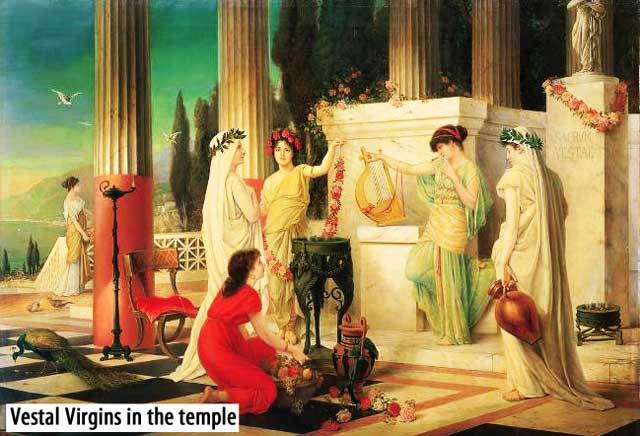

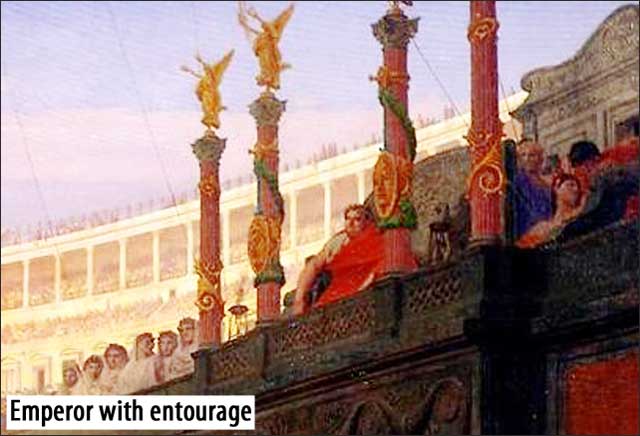

The other two entrances were for the emperor’s entourage, which included magistrates, senators, priests, and the Vestal Virgins.

The Vestal Virgins were six women, aged from six years old and upward, who served the goddess Vesta. They kept the fire of Vesta – the goddess of the hearth (fireplace), home, and family – constantly burning in the temple. It was believed that if the fire went out, Rome would fall.

The Vestals were also extremely powerful, they were able to free condemned prisoners or slaves by touching them, their words were unquestioned, and anyone threatening them harm would be killed.

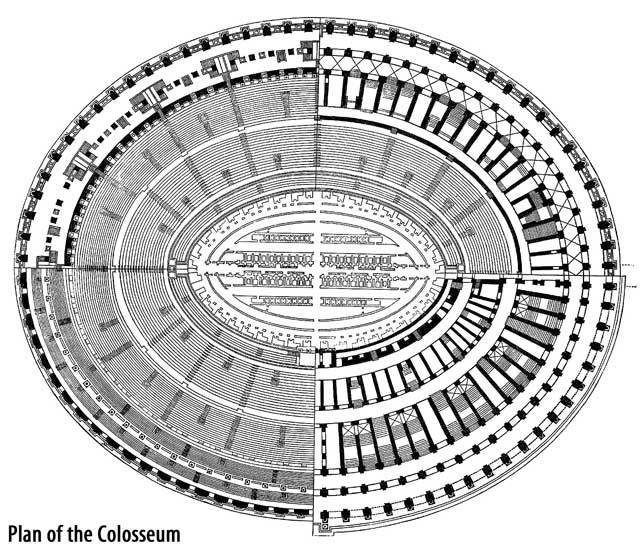

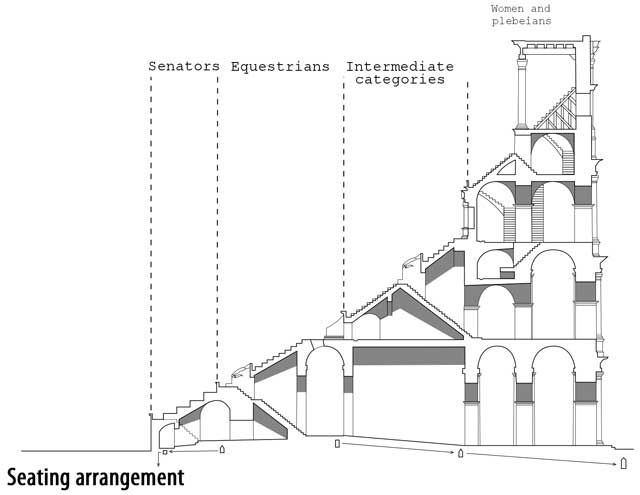

Roman kalendarium, or chronicles, suggest that the amphitheater was able to seat 87,000 spectators.

However, modern historians suggest that seating for 50,000 is a more accurate figure.

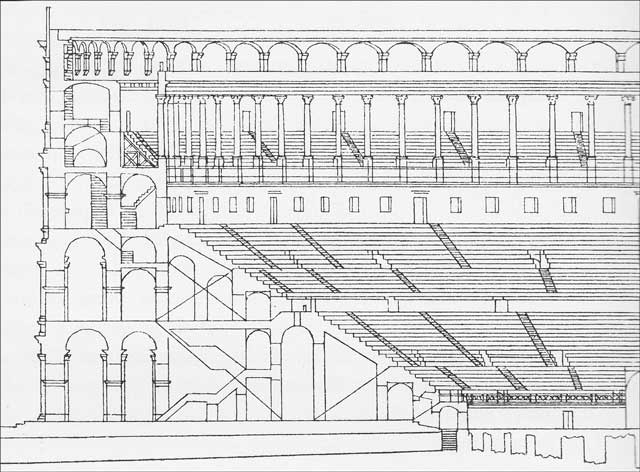

The amphitheater was constructed over four levels with arcades running around the perimeter.

There was access to the upper levels via steep stairways, and entrances to the seating area by 80 numbered passageways.

The four levels of seating had segregations for each of the different classes. The very highest was for women, the poor, and slaves.

This level had square windows, some of which can still be seen today on the northern side of the building.

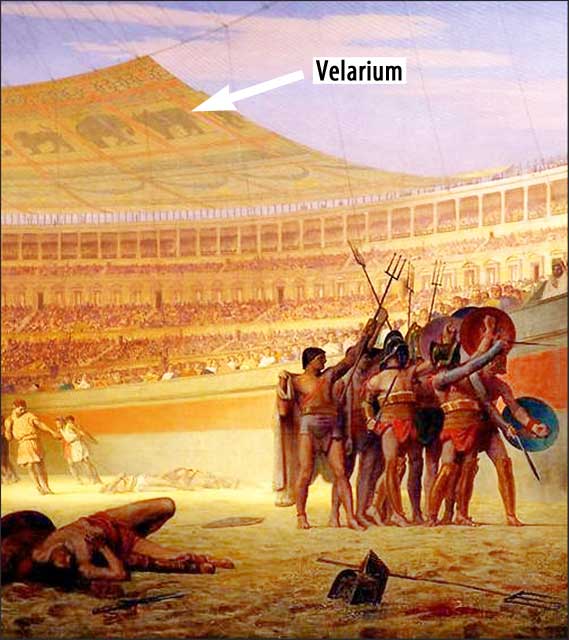

Above this floor, on the outside of the building, there were 240 brackets and sockets which anchored the velarium, or sails, onto wooden masts projecting out above the walls to create shade or to provide protection from the rain. The sails were hoisted into place by strong sailors of the emperor’s fleet.

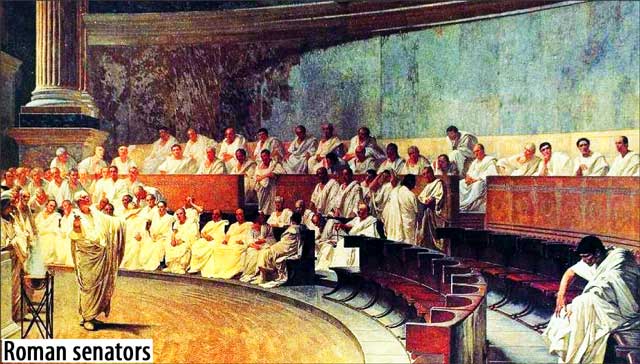

The third floor was for the plebeians, the second floor was for the rich Romans with valuable property, and the first floor, next to the arena, was for the senators, the emperor, and the Vestal Virgins.

Among these levels, there were also separate segregations. For example, on the second and third floors there were sections for boys who had not reached manhood and would sit with their tutors, another section for soldiers, and another for visiting foreign dignitaries.

The emperor and the Vestal Virgins sat in boxes on the short, central axes to the north. The remainder of the area was where the senators would sit, wearing their white togas edged with burgundy piping.

Some would bring their own chairs and sit on wide, open platforms; others would sit in the middle section, which had built-in marble seating.

On these seats, there were inscriptions of the senator’s names who sat there; other parts had seat numbers.

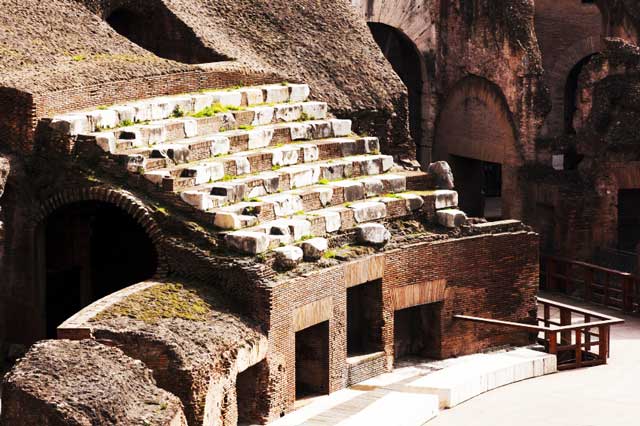

A small part of the seating area has been reconstructed.

At the second floor, you can see pieces of stone taken from this central seating area.

Among these pieces of stone is one with the inscription: “GRODIABLABI REGINIVC ETSP” and an almost heart-shaped symbol with a feather. This is the inscription and the demarcation sign of Senator Marcellus from the 6th century. The inscription acted like a seat number at a theater today – this would have been his seat.

But despite slaves and women being allowed to view the events, albeit from afar, there were a few classes of society who were banned from visiting the Colosseum altogether: gravediggers, actors, and anyone who had formally been a gladiator were among such people.

Today, the arena floor is open with its tunnels clearly visible, but in the Roman days, the series of 80 vertical shafts were covered with a hard wooden floor and trap doors, all hidden by a thick layer of sand.

Some of the shafts were used to bring stage effects, gladiators and animals in cages, to just below the arena floor; other shafts were used to channel water into the arena.

The display on the second floor is where you will find a number of stone weights, which were used along with a series of pulleys to open and close the trap doors.

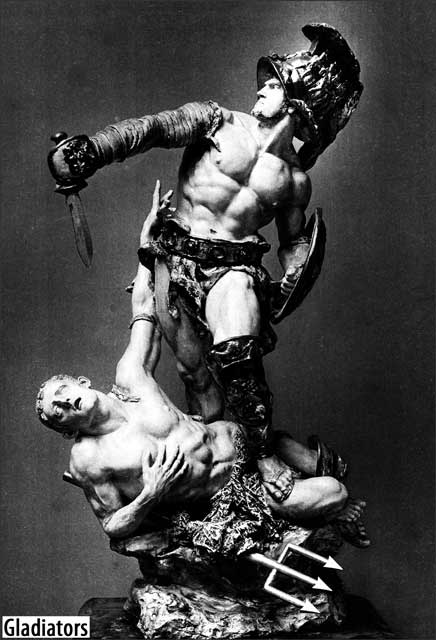

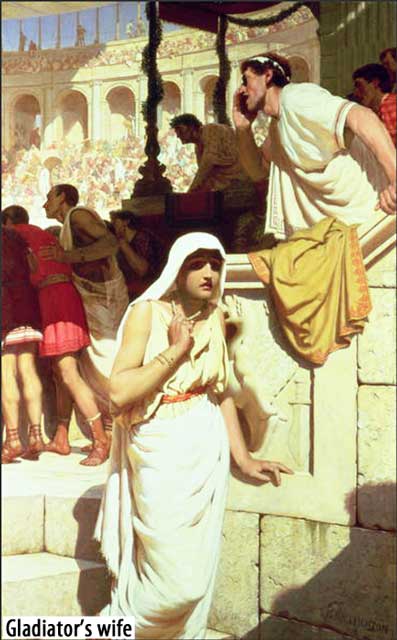

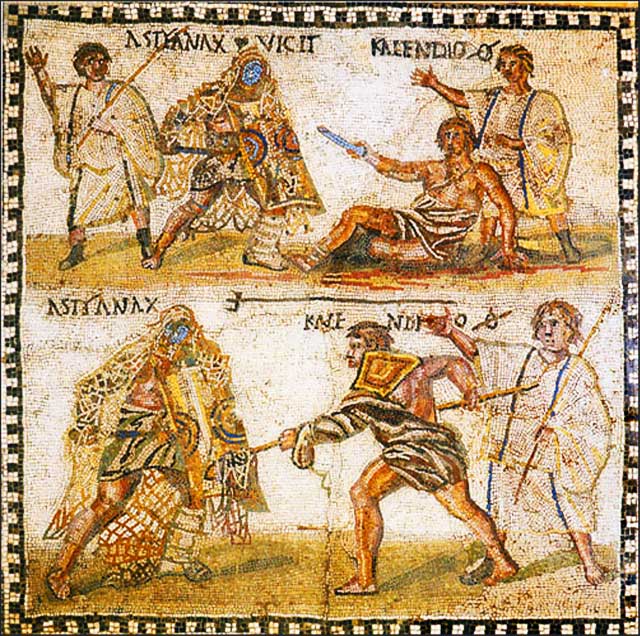

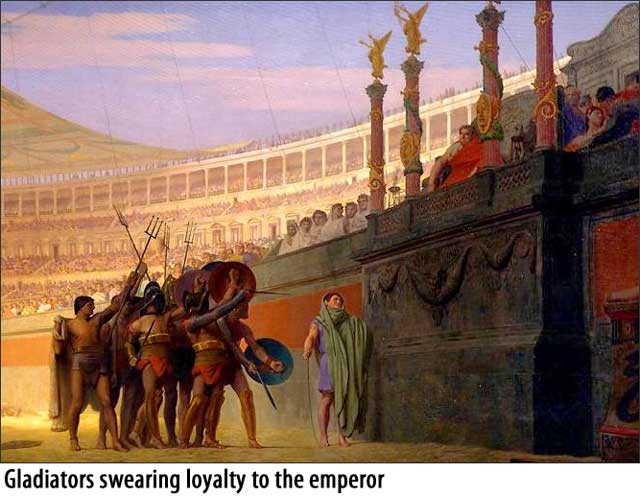

The most famous people of the Colosseum were, naturally, the gladiators. Usually, gladiators were condemned slaves or paid volunteers, schooled fighters who swore allegiance to a master and represented them in battle.

Gladiators went to gladiator school, a place to learn the techniques of how to fight and create a show. Ludus Magnus, or the Great Gladiatorial Training School, was the largest of the gladiatorial schools in Rome. It was situated next to the Colosseum and was connected to it by an underground gallery.

For the poor or for foreign citizens, the opportunity to learn a trade, to eat regularly and to have somewhere to sleep was a compelling enough reason to become a gladiator. But for paid volunteers the initiative was, for the most part, the promise of fame and fortune. If they were as successful as they hoped, the winners would become rich and adored by the public; they would be showered with gifts and prize money; women would faint, overcome with emotion and desire for such a strong, brave man at their feet.

Although some Roman men disliked the gladiators, perhaps because they were seen to be strong and able to attract women, they also secretly admired them. It was thought that the gladiator’s blood had special healing powers and that any man who drank it would receive greater sexual vigor. That made the gladiator’s blood both expensive and much sought after. It was also supposed to heal epilepsy.

However, very few of the gladiators reached divine status, and for most there was an extremely high probability that their lives would be cut short; the average gladiator only lived to be 30 years of age. Some combats would be a fight to the death, while others would be a matter of fate. The decision of whether a gladiator lived or died in these cases would be up the emperor, or the crowd. Those who were seen to fight well were often, but not always, spared. If a gladiator wanted to admit defeat, he did so by raising a hand and then it was the emperor or the crowd who would determine his outcome.

Gladiators were trained never to ask for forgiveness, never to cry out, and to accept death with dignity. Suffering a dignified death ensured that the gladiator’s soul was saved from sin and he was not branded as dishonorable or weak. To cry out was an absolute disgrace.

For those who died well, their departure from the arena was graceful, and once in the morgue, their armor would be removed, and their throat cut, just to make sure that they were dead. They also received an expensive cremation with offerings. On the other hand, gladiators who disgraced themselves were dragged from the arena either before or after being hit on the head with a large wooden club or hammer and their body dumped in the river or on wasteland.

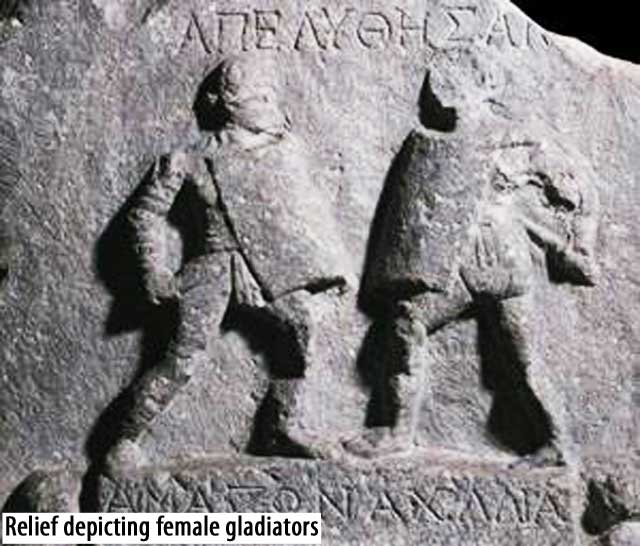

Women gladiators were known as gladiatrices or amazones, after the fierce tribeal women of the Amazon. Just like their male counterparts, they were recruited from prisoners of war and slaves, but sometimes wealthy Roman women fought in the arena.

For much of the time of the Roman Empire women were considered weak and needed to be under the control of their fathers or husbands. It is believed that their male guardians forced or encouraged their women to fight, in order to attract powerful Roman families to marry them.

Later, when women had some freedom, they may also have fought for thrills or excitement, although never for money, because if they did it would have made them as low as common prostitutes or actors.

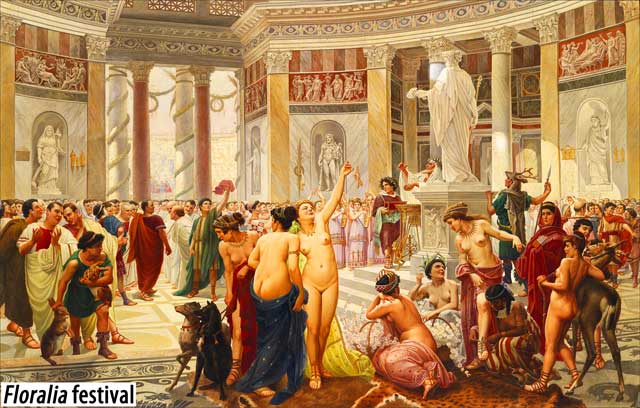

One of the best opportunities for women to be seen in the arena, and in the theaters of Rome, was a festival started by Julius Caesar known as Floralia. The festival honored Flora, the goddess of flowers, and included performances and plays by women and games in the arena known as Ludi Florales.

Spartacus was, and probably still is today, the most famous Roman gladiator, although he died 100 years before the Colosseum was built and obviously did not fight there. He rebelled against the Romans and their love of cruel sports; he escaped and raised an army, fought proudly, but eventually, along with many of his army, was killed.

There were other famous gladiators too, for instance Flamma, from Syria, who died at the age of 30. In his life as a gladiator, he fought 34 times, won 21 of those fights, and was defeated on only four occasions.

And then, there were Priscus and Verus, the two gladiators who performed on the very first day of the opening games of the Colosseum, back then known as Amphitheatrum Flavium. Priscus was a slave born in Gaul, an area in western Europe, and Verus was a prisoner who worked as a stonemason in the Colosseum. Verus volunteered to become a gladiator because, as he saw it, it was the only way he could escape the terrible working and living conditions; the heat and dust were killing him, and he knew he would die, one way or another.

The two gladiators entered the ring to roars from the crowd, their shields and swords highly polished and glistening. The men bowed to their emperor and the fighting began.

Both men were equally matched, strong, young and agile; they moved quickly striking and ducking with accuracy.

The contest continued in this way for a long time, neither one of them able to get the upper hand, until Verus lost his shield. The crowd gasped, was it the end? They had been taught well, and the rules of gladiator contests were known and adhered to by both of them – Priscus threw down his own shield.

Both men carried on fighting, but now they had no protection from their sword’s sharp edges, their arms and legs became slashed and bloody.

Then, in an attack by Verus, Priscus lost his sword; he was defenseless. Surely, that was the end. But Verus threw down his sword, the crowd cheered, and the fight continued with fists until they were both near the end of their strength.

Never before had the crowd seen such a fight. The men were tired and could fight no more, and at the same instant, they both raised their hands to admit defeat. Now it was for the emperor to decide what should happen to them. For the first and last time in history, Emperor Titus decided to declare both men victorious. He sent them wooden swords, the symbol of freedom, and palm branches, the symbol of victory. They were free.

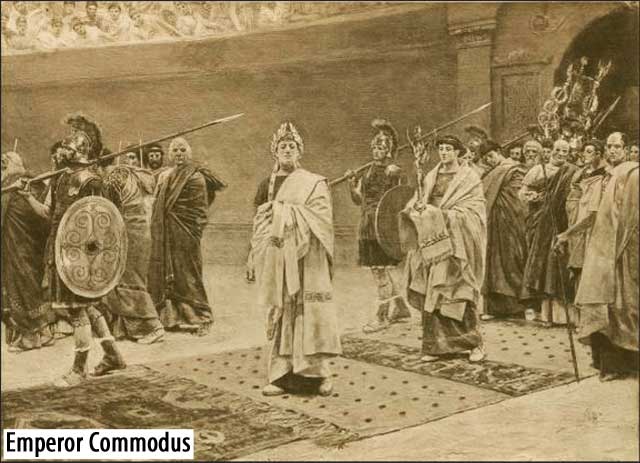

There were other, rather surprising gladiators too. Some of Rome’s emperors also enjoyed showing off their skills in the arena. Emperors Titus and Hadrian were said to have either publicly or privately performed in the arena, but it was Emperor Commodus, a dishonorable, crude, and cruel emperor who was the most renowned of all.

Emperor Commodus engaged in all kinds of different gladiatorial contests, much to the dislike of the Senate and many of the plebeians. He thought himself to be the resurrection of Hercules, the god of war.

He dressed and fought as a secutor gladiator, heavily armored with a short sword, who fought against opponents known as retiarius gladiators who had only light armor, a net, and a trident. He also fought as a bestiaries, or animal hunter, and this is one of the reasons he is remembered. On one occasion, he killed over 100 lions in one day, although he did this from a platform erected in the arena, so there was never much danger to himself.

On another occasion, and because he hated his senators so much, after killing an ostrich and cutting off its head, he crossed the arena and held it up before the disgusted senators. Then he shook his head and wagged his finger; implying one of the senators could be next if they displeased him.

After this gossip raged around the city, it was said that the reason he was interested in acting as a gladiator was that his mother, Faustina the Younger, had had an affair with the gladiator Martinaus and from that affair Commodus was born.

It was not unusual for Roman women to fall in love with a gladiator, and perhaps the story of Faustina the Younger is true and understandable. Gladiators appealed to women because of their strength and bravery; they were seen as real men, as opposed to, for instance, a boring senator. All over Rome, walls were covered with graffiti like: “Caladus the Thracian makes the girls sigh” and “Crescens the net fighter holds the hearts of girls.”

But it wasn’t just the women and girls who were attracted to the gladiators. The Syrian born emperor, Emperor Elagabalus, who became leader of the empire at the age of 15, also loved a gladiator.

Elagabalus became emperor in 218 and reigned for only four years under the name Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus, but in that time he had four wives and fell in love with a slave gladiator, charioteer Hierocles, declaring him his husband.

The story goes that during a gladiator fight in the arena, Hierocles fell in front of the emperor’s balcony, his long, blond hair tumbling from his helmet, and from that moment he became the emperor’s longest standing lover. But this kind of behavior was not appreciated by the masses, especially when the emperor declared, “I am delighted to be called the mistress, the wife, the queen of Hierocles.” There were also other stories that, as a husband, Hierocles beat the emperor as any man would beat his wife (back in those days).

Elagabalus’s lifestyle also brought an end to himself. He was captured by Roman soldiers, beheaded, and his body dragged through the streets before finally being thrown into the River Tiber. He was only 18 years old.

Most gladiators only fought in two or three sessions each year, with each lasting between 10 and 15 minutes on average. Combats could be one on one, or a group of fighters in the arena together. Victors received a palm branch, the symbol of victory, and an award from the sponsor, such as a crown, a gold coin, or a golden bowl. An impressive fighter would sometimes have the honor of a laurel crown and prize money.

Gladiators who lived long enough to die a natural death were buried in segregated cemeteries away from Roman citizens, their bodies said to be impure.

Just like today, details of forthcoming events would be advertised on notice boards giving details of the sponsor, date, the reason for the games, and the number of gladiator fights that would take place. There were also details of other highlights such as executions, music, facilities, and free gifts that spectators would receive. These included the use of the sunshade, water sprinklers, food, drink, and sweets.

The night before an event the gladiators enjoyed a feast with family and friends; this was to be a symbolic last meal for some of them.

On the day of the event, a comprehensive program was available for those who could read. Even some of the plebeians and poorest citizens of Rome could read and write, with the richer families having their children educated with private tutors or sent abroad to Greece to study. The program showed details of the gladiators, how many fighting sessions they had won, how many they had lost, and their area of specialty. This information was used to determine betting odds, and those spectators with enough money could place bets on the result of each fight.

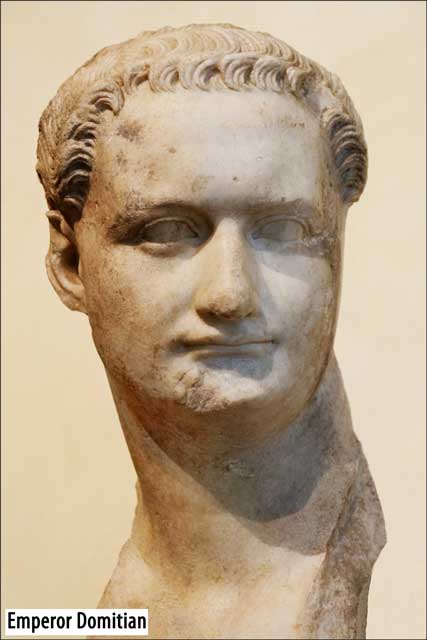

The last of the Flavian emperors, Domitian, liked to spice up his events, and in particular he enjoyed games which involved torch-lit fights between dwarves and women. These fights were part of the main act with bare-chested women fighting without helmets and many without armor.

The Roman people loved their games, even those who hated bloodshed found the atmosphere exciting. The emperors knew that providing entertainment for the people was an excellent way to stay popular, and so the Colosseum continued to delight for many centuries, but it also had its fair share of misfortune.

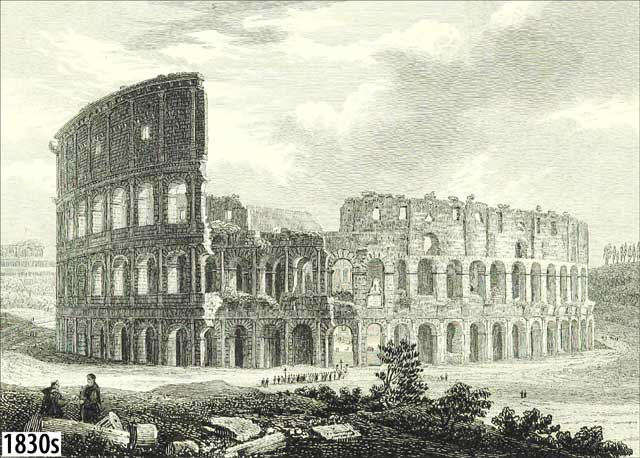

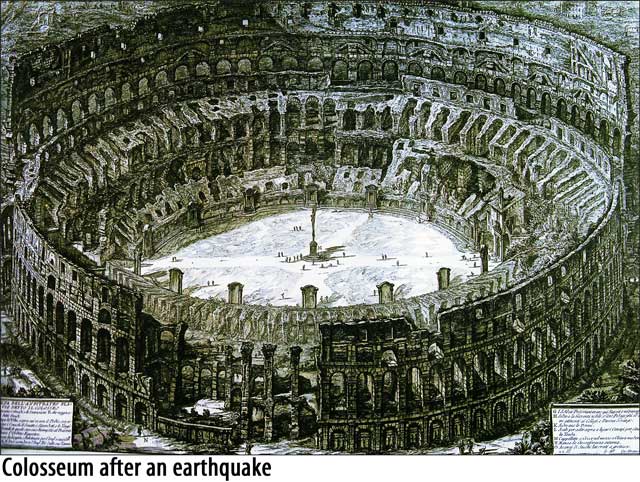

In 217, a lightning storm struck the heart of Rome. The fourth floor of the Colosseum, which was largely constructed from wood, was hit by lightning and the entire top floor was destroyed by fire. The fire also burned and blackened a large area of the lower levels so badly that the brick and travertine, in the area to the right of the northern entrance, had to be replaced, and the arena was not fully functional again until 240.

Despite this and other unfortunate events, use of the Colosseum continued for many years afterward, but in the end, the novelty of murder, animal slaughter, and fighting dwarfs became monotonous; the people wanted other types of entertainment. In 404, the last of the gladiator combats was fought, and in 523 the animal fights were banned. From this point, the Colosseum went into decline; it was left abandoned to the homeless, animals, and wild flowers.

The Colosseum also suffered severe damage from a great number of earthquakes; the largest in 1362, that caused the south side of the outer wall to collapse. Huge piles of rubble, brick, and travertine lay on the ground, but not for long. Citizens took advantage of the free building material which had suddenly become available, and soon pieces of the Colosseum were being taken to decorate private homes. However, it wasn’t just the citizens who took materials, the rulers of Rome also allowed materials to be taken and used to build roads, bridges, and houses; Palazzo Venezia and the Ponte Sisto bridge were two such constructions.

In the 16th century, an amusing idea came from the enterprising pope, Pope Sixtus V. He had an idea of turning the Colosseum into a wool factory to provide alternative employment for Rome’s prostitutes.

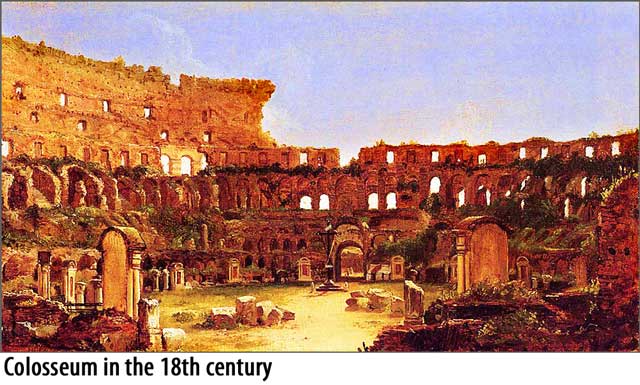

By the 18th century, there was very little stone left to be taken from the site and protection of what remained took over. The last surviving remnant of the outer wall on the northern side was reinforced with two brick supports, which added strength to what remained.

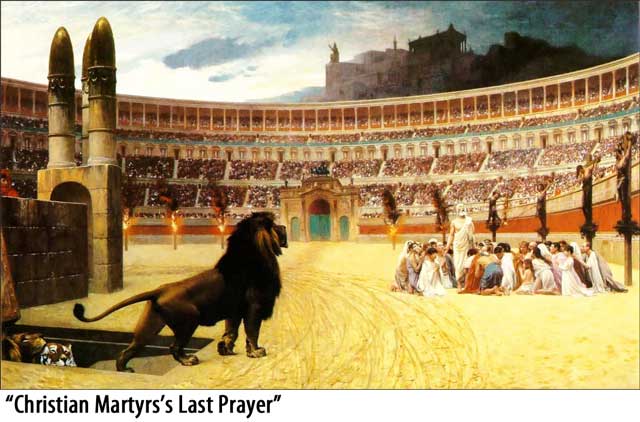

But it was not just the Romans who were interested in the Colosseum; from the 6th century the Church became involved in all matters concerning the mighty building, because on some occasions the Colosseum had been used as the site for the public executions of Christian martyrs.

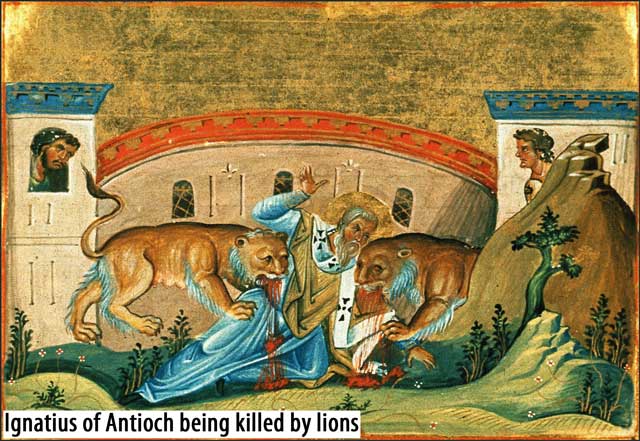

For instance, Ignatius of Antioch was killed and eaten by lions there. This is why Christian leaders wanted to make the Colosseum sacred. After the building had been abandoned by the Romans, religious orders used the space to establish a small church and used the land as a cemetery; the vaulted area under the arena was used as workshops and housing.

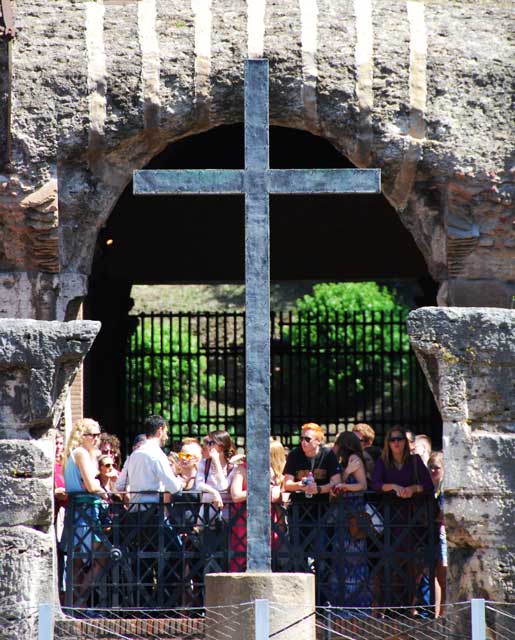

The cross stands there as a remembrance of those times.

On the outer wall is a plaque dedicated to Pope Benedict XIV.

He was responsible for declaring the Colosseum a national monument in 1749 and therefore saving it from ruin.

He was also the one who installed the big cross and 14 others, which have been removed.

Today the religious connection still continues with the pope starting a Good Friday procession and Mass from the site.

The Colosseum is the symbol of Rome and of course one of the city’s top places to visit. During its lifetime it has seen mighty rulers come and go; it has also seen death and violence.

Today, it is not excited Romans who visit for beast hunts and gladiatorial contests, but visitors of a different kind who come here to witness the remains of an incredible building and try to recreate an image of what happened here in its heyday.

The Colosseum certainly is an impressive building.

However, it was not the first, nor the largest arena to be built in Rome. That honor fell to the Circus Maximus, a mostly wooden construction five times the size of the Colosseum.

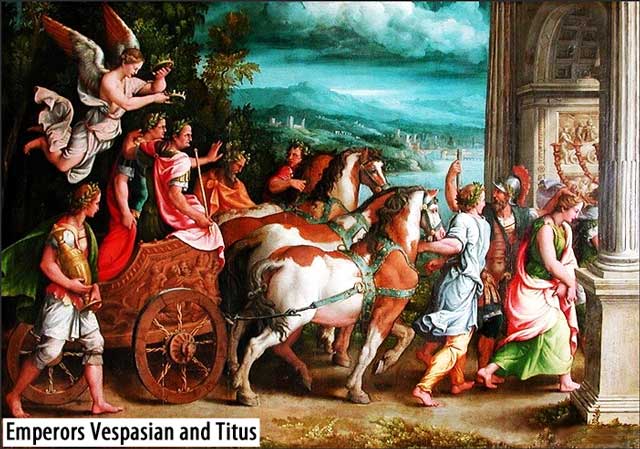

But, despite there already being one vast arena, which held chariot races and gladiator events, Emperor Vespasian started work on a new amphitheater in 70.

This was to be a permanent structure, not one made of wood, a magnificent oval auditorium, 189 meters (620 feet) long, 153 meters (502 feet) wide and 48 meters (157 feet) high. This was to be an amphitheater covered with over 100,000 cubic meters (3,5 million cubic feet) of travertine, which in turn was held in place by 300 tons of iron clamps.

Travertine was, and still is, used as a substitute for marble. It can be used, as it was in the Colosseum, as a thick tile to cover brick, just like tiling a bathroom. It can be used to carve statues, or it can be used in blocks to build arches, steps, or even whole buildings.

It is a white or cream limestone created by volcanic springs found between Rome and Tivoli to the east and can be polished to produce a shiny finish, giving the same effect as marble, or left unpolished to look like limestone.

Nine years into the project, in 79, Emperor Vespasian died and his son Titus became emperor.

At that time, the Colosseum already had three floors and was almost complete; all that Emperor Titus needed to do was to add the fourth and final floor. He did this within the first year of his reign, so in less than ten years the arena was finished.

Gleaming and new, it was named Amphitheatrum Flavium, after the family name of the emperors responsible for its construction, Emperor Vespasian, and his sons Titus and Domitian.

The mighty amphitheater opened its doors for the first time with an extravagant celebration lasting for 100 days. In true Roman style, this was the first of many spectacular events involving gladiators, exotic animals, musicians, and performing oddities, such as people with small heads, large bodies, or the obese.

The stadium was packed with 50,000 spectators all dressed in their finest togas, there were senators and noblemen, foreign dignitaries, and citizens of standing.

Farther away from the arena, on the upper floors were the plebeians, or ordinary citizens of Rome, and finally the plebeian women and slaves, who would watch the games from a distance.

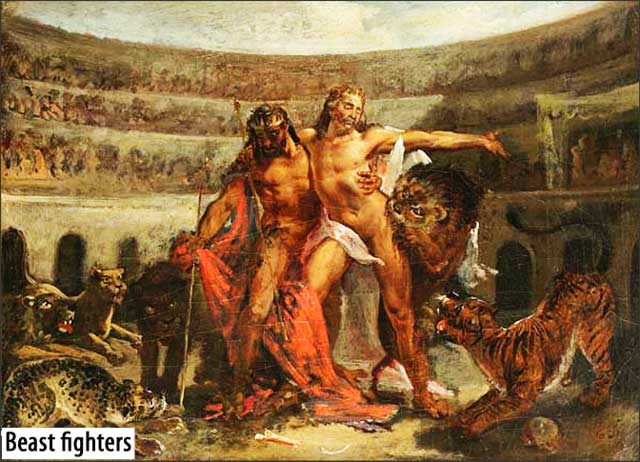

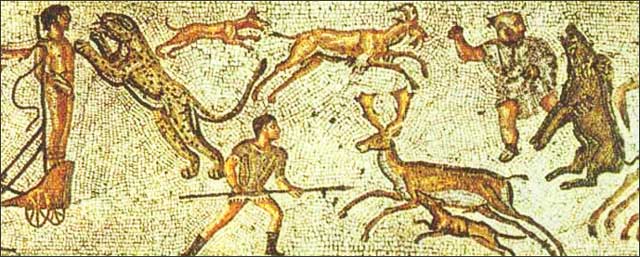

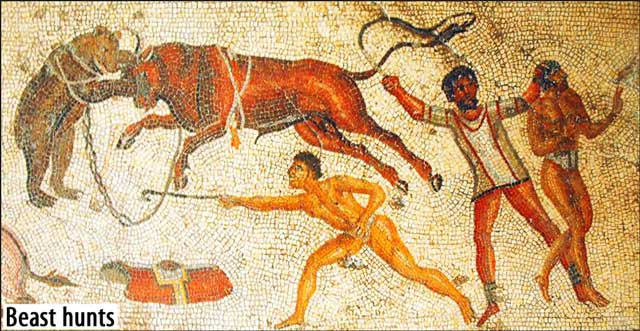

Excitement filled the air. The expectation was high at the thought of elaborate events, which included hunts with animals imported from Africa known as venatio, a word in Latin meaning a hunting game or chase.

There were strange looking creatures with long necks, others with strong, muscled bodies and aggressive roars, and some with sharp teeth that were found in rivers. To the plebeians these were mythical creatures from faraway lands.

The animal hunters were gladiators trained at the scholae bestiarum; one such school was close to the Colosseum, known as Ludus Matutinus.

They were special gladiators known as secutores, or chasers, retiarius, or net fighters, and bestiarii, or beast fighters.

These gladiators resembled barbarians armed with spears, knives, and sometimes whips. Their arms and legs were wrapped in leather straps, they wore canvas loincloths, helmets with visors and a decorative crest on top; sometimes they also wore sandals on their feet.

Although fighting tigers, lions, and other large beasts may sound dangerous, many gladiators volunteered to become beast hunters as it was less dangerous than other forms of fighting which often included a fight to the death.

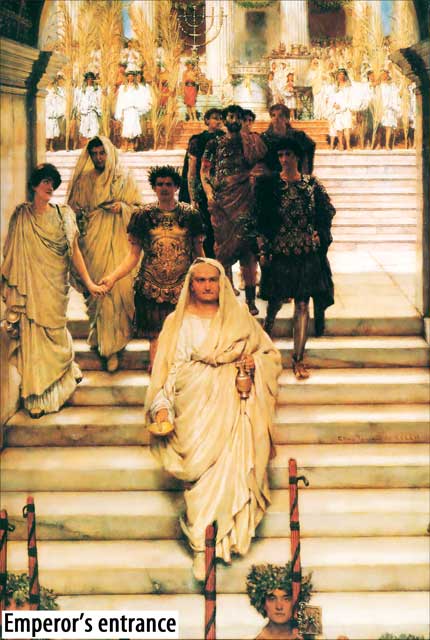

All the events were different, but the most elaborate started with the entrance of the emperor dressed in his finest robes. The crowd roared; they knew that this spectacular was to be one of the best, their host was generous and no expense would be spared for their enjoyment.

After the emperor’s grand entrance came a procession of slaves carrying images of both the emperor and the gods who were there to protect and entertain. There was Diana – the goddess of hunting; Jupiter – the king of all the gods; Charon – the ferryman to hell, in Roman times known as Hades; the god of wine – Bacchus; and the god of poetry, tales, and music – Apollo.

Next came the trumpeters playing fanfares and a scribe to record the events of the day, and then, the games could truly begin.

First there were informal, warm up sessions of fighting with unsharpened instruments. Then comedy fights between dwarves, but this was just a prelude of things to come.

Then came the beast hunts. Animals were pitted against gladiators who were trained on how to perform a daring show, where they appeared to take great risks and prove themselves to be brave, without actually causing too much danger to themselves.

Some of the animals were left unharmed and allowed to leave the arena to fight another day, others were not so lucky. In one event, it was recorded that 5,000 beasts were killed in just one day.

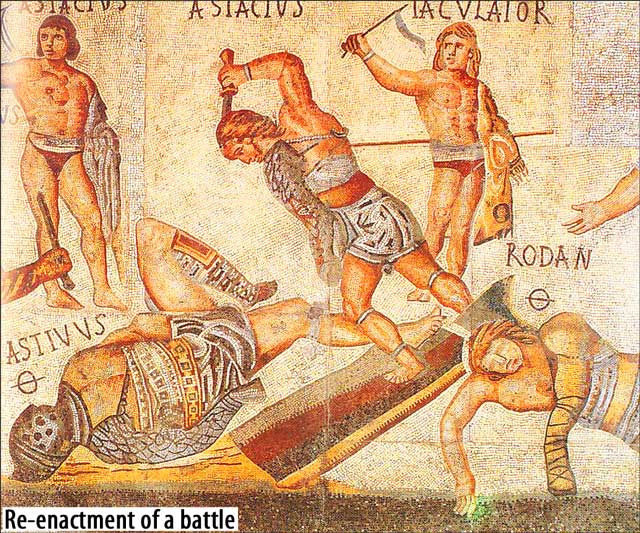

Next came the re-enactments, which were accounts of actual battles fought and won by the Roman legions, as well as mythological battles from Greek and Roman stories. The battles were gruesome, true to life and death, as many of the actors lost their lives just as the Roman soldiers had done in the real battles.

Usually the minor and most dangerous parts were played by slaves, criminals, and undesirable people dressed in military uniform, with the lead roles of Greek soldiers and Thracian soldiers, who fought with spears, being taken by gladiators.

Many battles were re-enacted, but two of the most popular were the battles between the Syracusans and the Athenians, and the battle of the Roman army against Hannibal, which also involved elephants.

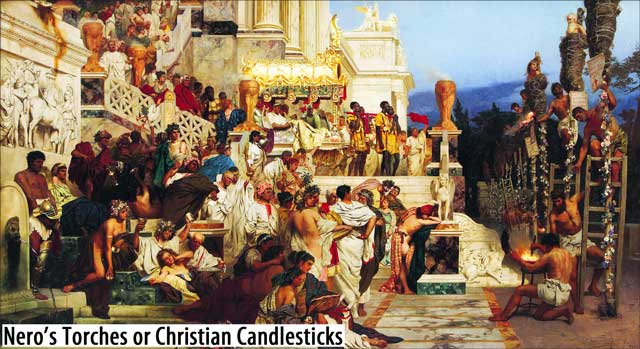

During some events, executions also took place. The executions, which were also held in other arenas throughout the city, were of criminals, army deserters, traitors, runaway slaves, and Christians, who were said to be guilty of antisocial behavior because they worshiped only one God. The Romans worshiped many gods, just as the Greeks had done.

The Romans sought out the Christians, persecuting and crucifying them just like their leader Jesus and his followers, and on some occasions the Colosseum was used as the site for their public executions.

These executions were inspired by mythology and included being burned to death, being nailed on a cross, stoning, or being eaten alive by beasts, which was known as damnatio ad bestia.

The worst and most cruel emperor, Emperor Nero, nailed his most hated victims, the Christians, to a cross and burned them alive to act as torches at dusk to light the arena.

The excitement would begin to grow even further with the entrance of the gladiators. They paraded around the arena in their extravagant purple and gold cloaks and lined up to swear loyalty to the emperor, “Hail Emperor! We men who are about to die salute thee.” This was the final and most extravagant part of the ceremony.

The gladiators marched off to wait their turn to fight, and when they re-entered the arena, they did so to a fanfare of trumpets and cheers from the crowd. They wore their finest armor adorned with feathers, precious stones, and covered with expensive metals, their slaves carrying large highly-decorated swords, which were a demonstration of both the gladiators’ wealth and power.

There would be special bouts of fighting involving left-handed gladiators who fought right-handed opponents.

In between the matches, musicians would entertain the crowds who would also enjoy gifts of food and wine offered by the sponsor of the event.

Not all the games in the Colosseum were sponsored by the emperor; anyone with enough money to put on a spectacle was encouraged to do so. Many of Rome’s richest citizens were the senators. They believed that the more money they spent on providing the best games, the more votes they would receive at election time, so an incredible amount of effort was put into creating memorable events throughout the year that the plebeians would appreciate.

This was known as panem et circenses, which translates to bread and circuses. These were the words used to describe the way of influencing power over the Roman people by offering them pleasures such as food and entertainment, keeping them quiet and peaceful, but at the same time giving them the opportunity to voice themselves in these places of performance.

This was especially true of Julius Caesar, although this was before the Colosseum was built. He was famous for organizing magnificent games and borrowing lots of money to pay for them. But, because the people believed he had done it for them, he got their votes and was able to pay back everything he owed; other rulers followed this example.

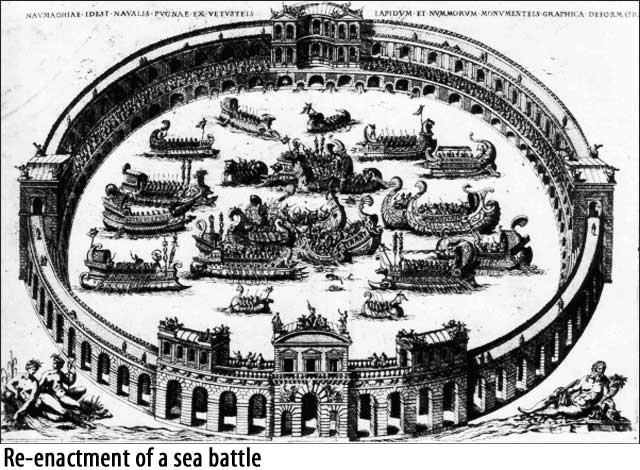

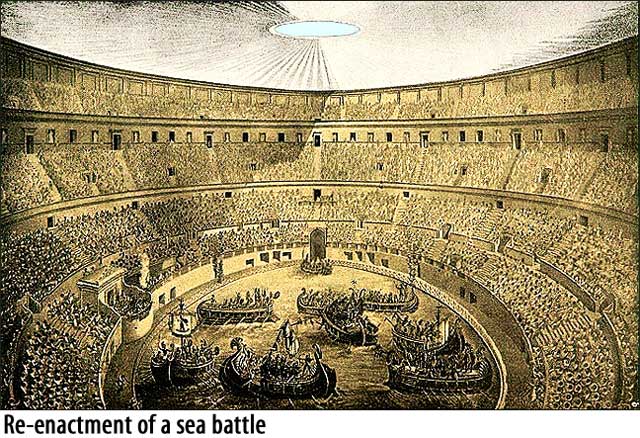

During each of the annual events or celebrations, different games and matches were held. In addition to the animal hunts and grand fights of the gladiators, there were sylvae, or recreations of natural scenes with real plants and animals from around the world. Many naumachiae, or sea battles, were re-enacted on lakes within the city, but the Colosseum was also used as a venue for such events.

During the 100 days of opening celebrations, Emperor Titus filled the arena with water and brought in bulls, horses, and domestic animals who had been taught to swim. He also staged a sea battle, which replicated the battle between the Corcyreans and Corinthians.

It is believed that, because of its size, the Colosseum could only reproduce small battles or battles where ships were made to scale rather than full size versions.

But how did Amphitheatrum Flavium become known as the Colosseum? This dates back to long before the Colosseum was even built.

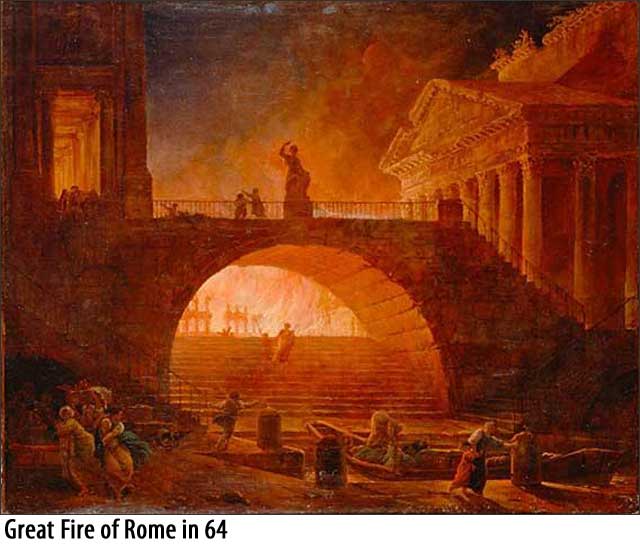

Following the Great Fire of Rome in 64, the emperor of the day, Emperor Nero, confiscated large amounts of his citizen’s private land and claimed it for himself.

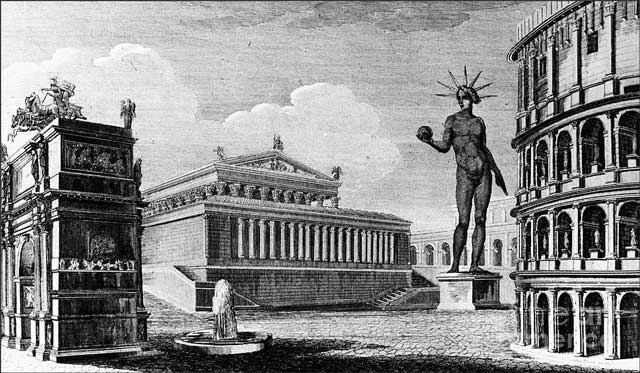

On some of this land, in the center of the city, he built a magnificent palace, the Domus Aurea. In its grounds, he built aqueducts to channel water to a series of gardens with artificial lakes and pavilions, and in one garden he built a statue, the Colossus of Nero. The Colossus was 30 meters (100 feet) high with a face modeled on Nero and the body of Helios, the sun god.

The Flavian family inherited these confiscated lands, but unlike Nero, they were compassionate toward their people and wanted to restore their land back to them.

As well as being compassionate, they also wanted to celebrate the grand victory of their battle in Jerusalem, so the gardens and lake were laid flat, and the Amphitheatrum Flavium, an amphitheater for the people, was constructed.

But the name was yet to be changed to the Colosseum. In the 8th century a monk, Venerable Bede, made a statement in Latin: “Quamdiu stat Colisaeus, stat et Roma; quando cadet colisaeus, cadet et Roma; quando cadet Roma, cadet et mundus.” This translates to: “As long as the Colossus stands, so shall Rome; when the Colossus falls, Rome shall fall; when Rome falls, so falls the world.”

Venerable Bede was talking about the statue, the Colossus, but over the years, the name was transposed to the Colosseum, as by the year 1000 the statue had fallen, Rome was still strong, and the name Colosseum had stuck to the amphitheater.

Italian Traditions and Customs

Every country has its own traditions, customs, and etiquette, and Italy is no different, the country revolves around tradition. There is a meaning behind everything, much of which is closely linked with Catholic religion.

Italian etiquette, customs, and traditions are, in most cases regional and date back centuries. However in some circumstances, as time moves on, they are slowly being changed to create a new way of doing things.

With huge regional differences, Italy does not really have a set etiquette, and something, which would be considered rude in one region, may be thought of as polite in another. But in general, Italians are happy if you show respect for their family and friends, their religion, and if you pay attention to their clothes (and yours).

It is known as bella figura or the good impression, and if you compliment them on this you will be a friend for life.

If you’re invited to the house of an Italian, giving flowers is not common, but it is polite; however, there are a few things to remember about flowers. Chrysanthemums are symbols of sorrow and death, as is a bouquet containing only three flowers. It is considered rude to give yellow flowers as these symbolize anger and jealousy. Red flowers suggest love and secrecy, so unless you’re in love with your host, choose another color.

Italians pay attention to good quality gifts.

They especially appreciate luxury chocolate or expensive wine.

Once received they will open the gift at once, as leaving it unwrapped or not paying attention to it is usually considered impolite. The last piece of advice regarding the giving of gifts is never to wrap a gift in purple, as this is a sign of bad luck.

As the family is one of the most important things to an Italian, a baby is cause for great joy. When a baby is born, its parents usually put fiocci or a large shaped bow (a ribbon tied nicely) in a prominent place outside the house as a sign; blue for a boy, pink for a girl.

Parents, relatives, and friends do not buy many gifts or items for the baby before it is born; some may not even set up its nursery until the very last minute so as to ensure the healthy arrival of the child (Italians are a bit superstitious).

Once the baby has been born it is then showered with presents.

Very soon the baby is baptized, but not before a name is chosen. In Italy, there is an old tradition, which often causes family members to have the same name, as the first son is named after its father’s father. The second son is named after its mother’s father, the first daughter is named after its father’s mother, and the second daughter is named after its mother’s mother. Men of the family are always thought of as highly important, so if a girl is the first born some parents (wanting to show respect for the paternal grandfather) and also for good luck, give the girl a female variation of her father’s father’s name (her grandfather’s name). For example if the grandfather’s name was Angelo, she would be Angela, Carla for Carlo, Giuseppina for Giuseppe, Vincenza for Vincenzo, and so on. Other children are often named after the patron saint of the day to please the saints, they can be named after other relatives, or even the day of the week such as Domenica or Domenico meaning Sunday.

As you can imagine giving the paternal grandfather’s name to all the firstborn sons of the big family can be very confusing, especially when families have two or more grown up sons who all become fathers. To solve the confusion, Italians use nicknames. The tradition is still practiced in many places, especially in the smaller towns and villages. Nicknames are usually derived from the child’s personal characteristics and they are known by this nickname throughout their life, one example would be the nickname Orso Rosso (red bear) for a child who is always angry.

Today in modern families people are beginning to get away from naming traditions and nicknames, and while respectful of their Italian custom, they are beginning to exercise free will with regard to naming their children.

Once a name has been given, the child is then baptized, usually into the Catholic faith.

The parents choose a godmother, madrina, and a godfather, padrino, whose duty it is to make sure that the child is raised in a proper religious manner.

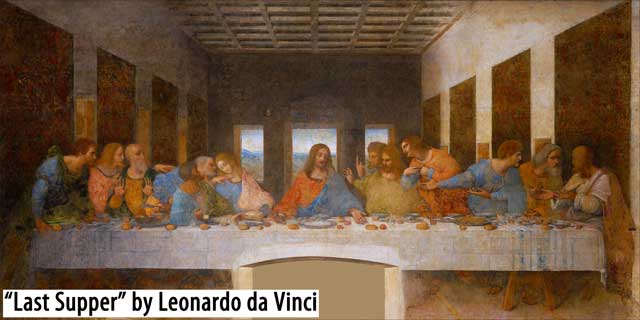

The next stage in a child’s life, usually around the age of seven or eight, is the first communion, which is almost as important as a marriage.

The first communion is when a Catholic child takes the “body and blood” of Jesus Christ for the first time to remember Christ’s last supper.

The first communion is one of the more strict traditions and has been celebrated in the same way for centuries.

The child wears elaborate clothing.

Girls wear white first communion gowns made of silk and place veils over their heads, boys wear suits with ties.

Relatives offer food and gifts, these can be a mixture of conventional gifts – religious items such as Bibles, silver cups, statues, and rosaries. Often, family heirlooms – things which are handed down through the family – are also given to the child.

Today, besides these gifts, children are also showered with expensive smartphones, tablets, watches, and electronic goods, rather like at Christmas.

Following the first communion, a party with food, music, and dancing is always given, and as you would expect, this party is for all family and friends so it can be an extremely large gathering, which goes on for many hours.

The tradition of the first communion is to serve pizzelle, a sweet waffle made especially for the children.

Birthdays are not surrounded by tradition, unless of course it is an 18th birthday, but even then the celebration is not as grand as other times in a child’s life.

Large parties are common, parties which invariably involve eating and dancing.

Perhaps the most different thing about an 18th birthday is that meals tend to be buffet style rather than the traditional sit down meal.

One thing that is a tradition on birthdays, however, is to pull the ears of the child according to the number of years of their age, so 18 years gets 18 ear pulls.

Tradition in the marriage ceremony is another area where couples are starting to exercise their own ideas rather than doing things according to tradition and by the book.

It is also true that each region has a different tradition and way of doing things, but here are a few customs which are common and have not died out in many areas.

In general, permission of the bride’s family has to be sought before an official engagement can be made.

Some couples may be engaged but do not buy a ring until nearer their marriage, others buy one straight away. It is traditional for the groom’s family to provide the ring, or the means to pay for it.

The wedding itself is usually held at a morning Mass in a church.

There are several superstitions and traditions, for instance a ribbon will be tied on the door of the church to symbolize the bond between the couple.

As green brings good luck, usually one of the wedding party wears something green, however small.

Traditionally, marriages should not take place during Lent or Advent, they should also be avoided in May and August, which only leaves just over six months of the year to have a ceremony. Sundays were thought to be the best and most auspicious day to marry.

In Veneto, it is customary for the couple getting married to walk to church together. The people of the town place obstacles in their path to see how the bride will react in domestic situations. For example, if she picks up a broom she will keep a clean house and if she stops to help a child that has been put in her way she will be a good mother.

In Veneto, and in other regions, the couple have to cut a log of wood in half using a double-handed saw before they reach the church, this represents their partnership in marriage. To ward off evil and jealous spirits, the groom may carry a piece of iron in his pocket and the bride wears a veil.

The tradition of the veil began in ancient Rome when it was used to hide the bride from any spirits that would corrupt her. The bridesmaids also wore similar outfits so that the evil spirits could not distinguish who was the true bride.

In Roman times it was customary that the bride was carried into her new home by the bridegroom.

Another Roman custom was that the bride threw nuts at all the men she had rejected as husbands as she left the church.

The bride may also carry buste, a satin bag in which guests place envelopes of money. This was customary before the giving of gifts, as it helped pay for the lavish ceremony and the reception afterward. Sometimes the bride would also wear her buste after the ceremony at the reception and if a man wanted to dance with her he could do so in exchange for placing money in the bag.

The ceremony is followed by a daylong reception and feast.

Food, as you would expect, also plays an important and symbolic part in the marriage celebrations. Foods which promote fertility and good luck are often tossed at the newly married couple.

Confetti, almonds covered in a crunchy sweet icing and tied in mesh bags are such things; an alternative is wanda, twists of fried dough powdered with sugar, although these are not thrown.

Sparkling wine, Prosecco, and drinks are served to the guests by the best man before the dinner begins. With these drinks, the guests make a toast to the happy couple.

They raise their glasses and shout “Per cent’anni!” that means “For a hundred years!”

There is also another traditional toast made by a male guest after a few glasses of wine, “Evviva gli sposi!” – “Hurray for the newlyweds!” This toast is shouted at any time during the reception whenever the sound of raised voices becomes less (it will never be quiet); guests respond with thunderous cheering and clapping, and the noise levels rise once more.

The menu at the wedding reception is nearly as important as the wedding itself.

At other celebrations there may be up to eight courses, but at a wedding, guests may be served as many as 14 different courses with wine and other drinks.

After dinner a multi-layered wedding cake is served with espresso.

Once the eating has finished the celebrations move on to another key Italian wedding custom, tarantella, which is the couple’s first dance set to traditional Italian music.

The couple stand in the middle of the room whilst the guests surround them and dance in a circle.

Before the reception is over there is one more custom to be completed, the bride and groom break a glass.

The number of shattered pieces suggests how many years of happiness the couple will share.

Italian funerals follow the rules of the Catholic Church. Traditionally this will be a Mass with last rites and an open casket so that mourners can kiss the forehead of the deceased person.

In most cases, the funeral is the day following the death. The body of the deceased is brought home and placed in a quiet room where visitors can come and pay their last respects. Posters announcing the death are put up around the vicinity of the deceased person’s home giving details of the time and location of the service.

Custom says that at funerals everyone wears black; while this is traditional it is not always the case. In the countryside many people have no need for a suit, or they may be working in the fields and come straight from whatever they are doing to the funeral, so in many cases people will wear ordinary clothes.

All funerals are somber occasions, and at many services you can expect to witness what is known as prefiche, an act historically performed by women. Prefiche is when the women who accompany the funeral procession pull their hair, wail, and throw themselves onto the coffin in great sadness. This is especially true with Mafia funerals, those who have died in an accident, and those of children; when a person has died of old age prefiche is less common.

After the service, mourners follow the coffin to the gravesite.

Here, the body is interred in a small house-like structure in a block, rather than being buried in the ground.

Cremation is also becoming increasingly common.

After the ceremony, mourners attend a reception held at the family’s home, bringing with them food to comfort the family and to feed the guests.

But the funeral is not the only time when the deceased is mourned. On November 2 Il Giorno dei Morti (Day of the Dead) is celebrated. This is when the graveyards are full of people who decorate the graves and light candles for their loved ones.

In addition, every year on the anniversary of their death, messa di suffraggio, a special Mass to honor the deceased person is held and small pictures of them are given out, so as not to forget.

Travel guides that show you around and tell stories, not just history.

Dear Traveler, please review this book, we truly appreciate your feedback.

Are you exploring famous landmarks in cities around the world? Are you looking for more insight than a typical guidebook provides you? Perhaps you would like your own personal tour guide but prefer to visit places at your own pace? Are you curious about how people lived in those palaces and castles? Maybe you just want to understand people from different cultures better? Well, we have exactly what you need, we tell WanderStories™.

WanderStories™ is the best local guide for you, showing you around and telling stories of famous and interesting sights, in an e-book on your tablet, smartphone, or computer.

WanderStories™ travel guides are unique because our storytelling style puts you alongside the best local guide who tells you fascinating stories, while a wealth of high quality photos, historic pictures, and illustrations brings your tour vividly to life.

WanderStories™ travel guides are e-books that include lots of photos, maps, and illustrations and tell you the stories behind the history of the places you will visit, like the best personal tour guides would do. In fact, they do it so well that you can visit the most extraordinary places around the world without even leaving the comfort of your armchair. Wherever you are, you can experience the excitement of history being recreated around you as the story unfolds.

You will get to know how real people, emperors and sultans, concubines and eunuchs, slaves and executioners lived in the palaces you will visit; what gods the monks worshipped in these temples; how generals and soldiers, crusaders and gladiators fought and won…or died. You will learn about local traditions and customs, holidays and festivals, cuisine, even jokes.

Whether you’re at home, on your travels, or walking in the historic setting itself, WanderStories™ is the best personal, local guide on your tablet, smartphone, laptop, or computer.

We, at WanderStories™, are storytellers. Our mission is to be the best local guide that you would wish to have by your side when visiting the sights.

Our promise:

• when you visit a city with a WanderStories™ travel guide you will have the best local guide at your fingertips

• when you read a WanderStories™ travel guide in the comfort of your armchair you will feel as if you are actually visiting the best sights in the city with the best local guide

Please get WanderStories™ travel guides at: wanderstories.com

Please subscribe to the FREE WanderStories™ travel e-magazine, Armchair Travel Guide at: wanderstories.com/travel-magazine

Sample from: Rome Tour Guide Top 10

Copyright © 2015 WanderStories

Photos and illustrations provided by WanderPhotos™, exceptions are as follows:

Siren-Com is the author of the following photo:

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or distributed in any form by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems without permission in writing from the publisher.

Disclaimer. Although the authors and publisher have made every effort to provide up-to-date and accurate information, and have taken all reasonable care in preparing these publications, they accept no responsibility for loss, injury or inconvenience sustained by any person relying on or using our publications, and make no warranty about the accuracy or completeness of their content and, to the maximum extent permitted, disclaim all liability arising from their use.