Eiffel Tower

Louvre

Musée d’Orsay

Arc de Triomphe

History of Paris

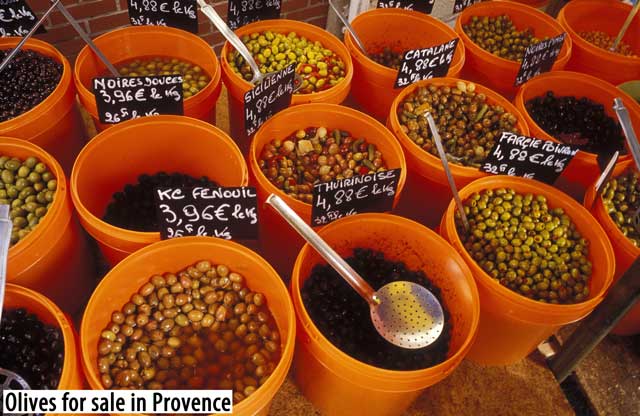

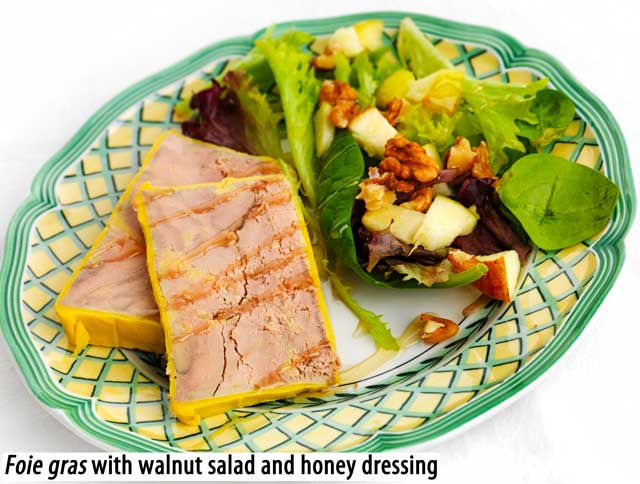

French Cuisine

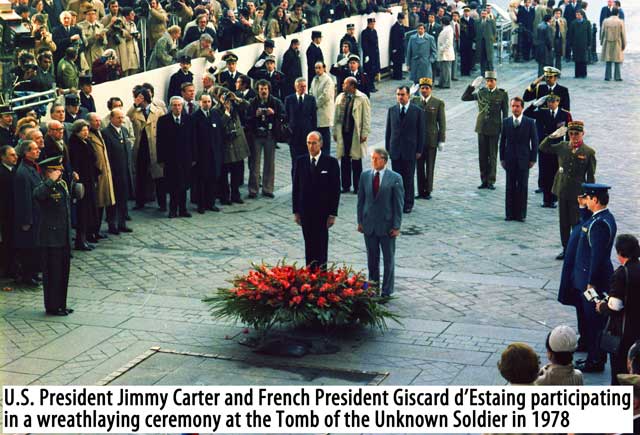

French Traditions and Customs

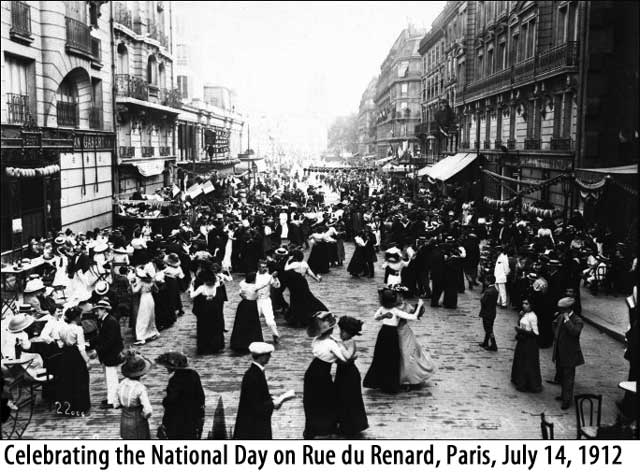

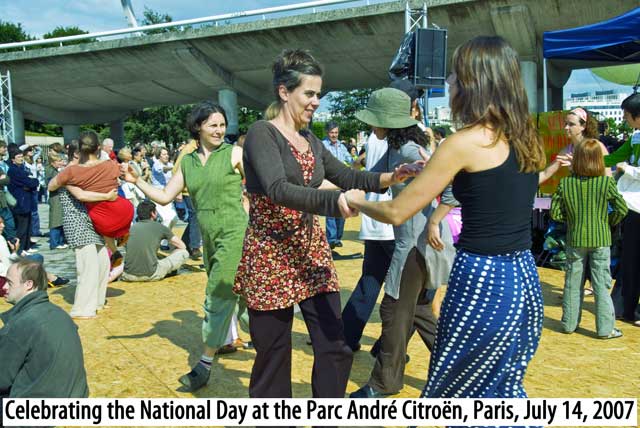

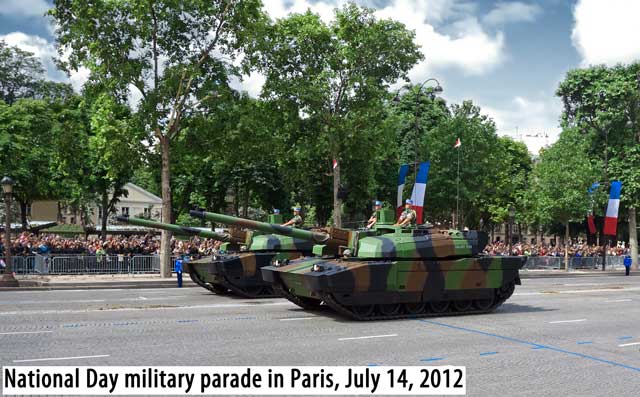

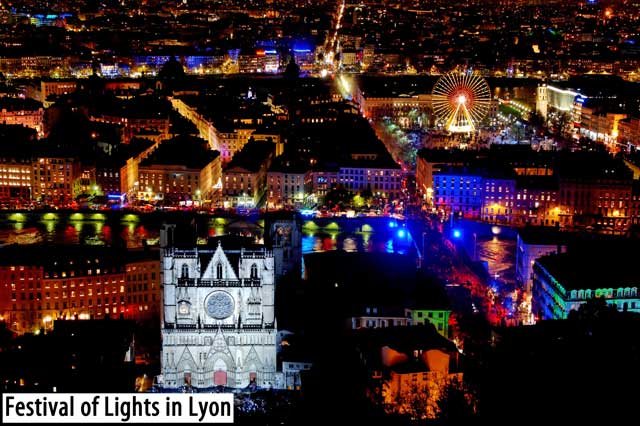

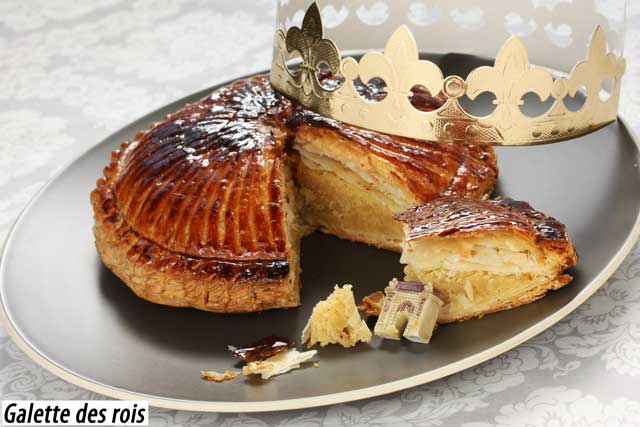

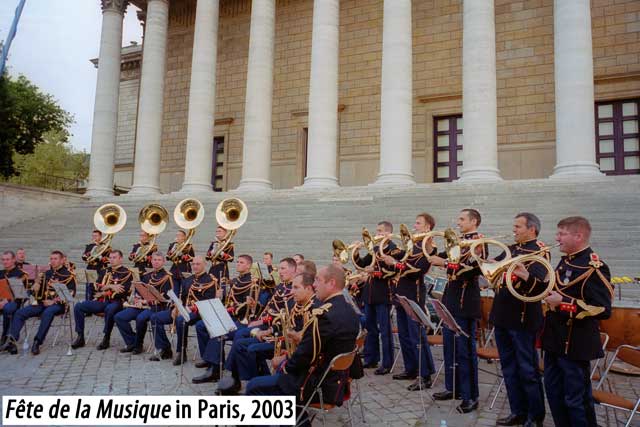

French Holidays and Celebrations

French Humor

What Makes the French so French

Welcome to the WanderStories™ tour of the top 5 sights in Paris: the Eiffel Tower, the Louvre, Notre-Dame, the Musée d’Orsay, and the Arc de Triomphe. We are now ready to take you on your personal tour of these world famous landmarks.

We will also tell you the brief history of Paris and several additional stories about French cuisine, traditions and customs, holidays and celebrations, humor, and what makes the French so French.

We, at WanderStories™, are storytellers. We don’t tell you where to eat or sleep, we don’t intend to replace a typical travel reference guide. Our mission is to be the best local guide that you would wish to have by your side when visiting the sights. So, we meet you at the sight and take you on a tour.

WanderStories™ travel guides are unique because our storytelling style puts you alongside the best local guide who tells you fascinating stories and unusual facts recreating the passion and sacrifice that forged the beauty of these places right here in front of you, while a wealth of high quality photos, historic pictures, and illustrations brings your tour vividly to life.

Our promise:

• when you visit these top sights in Paris with this travel guide you will have the best local guide at your fingertips

• when you read this travel guide in the comfort of your armchair you will feel as if you are actually visiting these top sights in Paris with the best local guide

Paris is considered to be one of the best-loved and most beautiful cities in the world. With a history riddled with intrigue, war, revolution and scandal, its attraction is irresistible to the traveler.

Paris has a glamorous image as one of the world’s major tourist destinations and as a center for culture, fashion, luxury goods, and of course everything romantic. With its ancient and more recent history, fabulous architecture and marvelous heritage, visiting Paris is definitely an unforgettable experience. There is only one thing to do now – visit!

Let’s go!

Your guide, WanderStories

Once you have read this book please review it, we truly appreciate your feedback.

Please subscribe to the FREE WanderStories™ travel e-magazine, Armchair Travel Guide at: wanderstories.com/travel-magazine

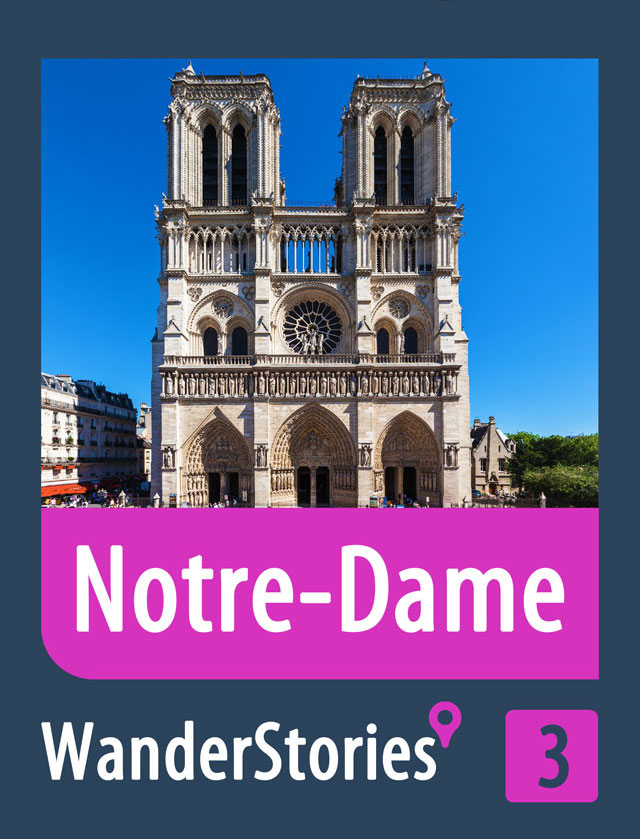

Notre-Dame

Address: Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris, 6, Place du Parvis Notre-Dame

48°51'11.9"N 2°20'56.6"E

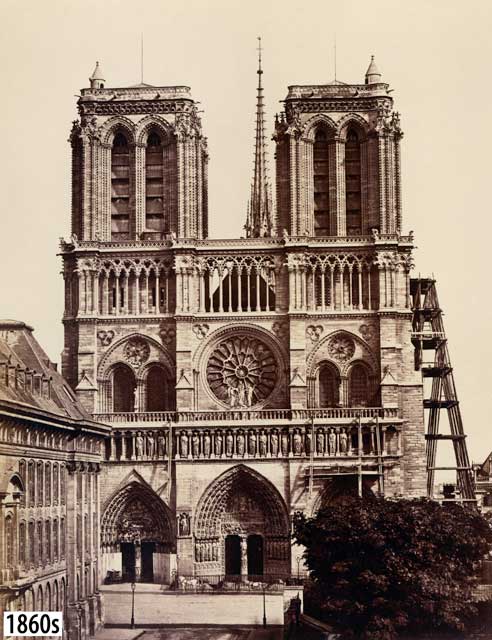

The Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris is among the most visited tourist sites in the world.

Standing in front of the cathedral, you can’t help but feel like everyone else who visits here, whether pilgrim or tourist, the magic of this inspirational Gothic building.

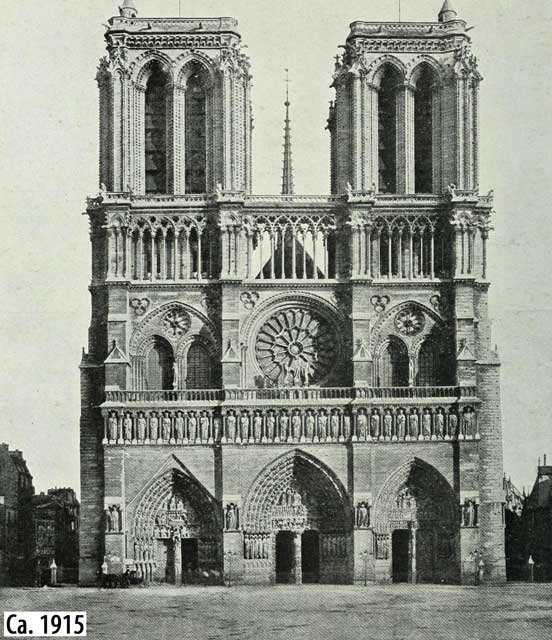

Notre-Dame is widely considered to be one of the finest examples of French Gothic architecture, and it is among the most well-known church buildings in the world.

Long before the first foundation stone of the cathedral was laid in 1163, this was a sacred site for other civilizations. The Parisii tribes living here as early as the 4th century B.C.E. worshipped a mixture of gods and nature spirits. The most important of those was Cernunnos, the horned god, but it was probably Toutatis, a god of winds, journeys, and boundaries, who was worshipped here, on the bank of the river.

Then the Romans conquered the area and built a temple to Jupiter in the 1st century.

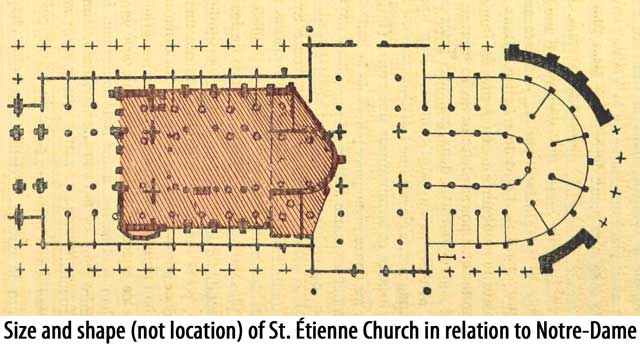

The Roman temple was later replaced by a large Christian basilica with five naves, dedicated to St. Étienne (also known as St. Stephen). It is not known if this basilica was built in the 4th century and was later renovated or whether it was built in the 7th century with reused elements. But it is known it was magnificent, inside there were marble columns and the walls were decorated with mosaics.

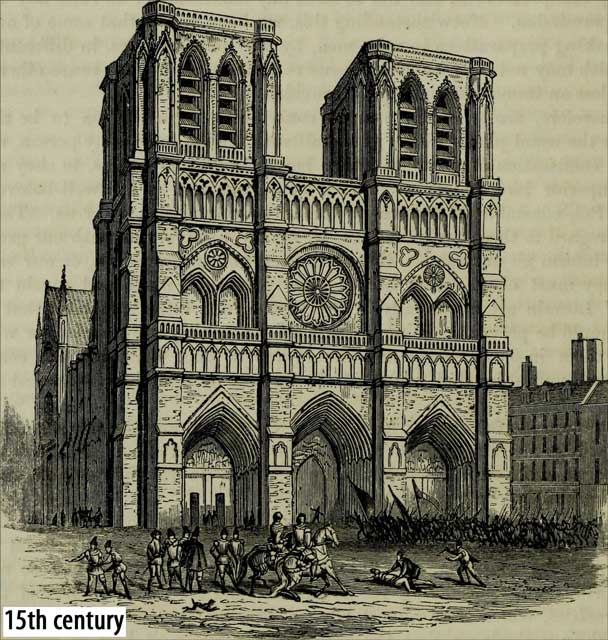

In the early 12th century Maurice de Sully, bishop of Paris, decided to build a new cathedral for the expanding population. The foundation stone of the cathedral was laid in the presence of Pope Alexander III in 1163. But building such a huge cathedral was a long process and it was not completed until around 1345.

It is believed that Notre-Dame was built on a ley line, a sacred Earth meridian. These meridians connect ancient places of worship, such as the site of the Louvre aligned to the site of the Arc de Triomphe on an east to west axis. Notre-Dame, similarly, is connected on a northeast to southwest line to Chartres Cathedral. Sacred geometry was thought to bring the individual closer to the divine, and sacred sites, whether ancient pyramids, Roman temples, or Christian churches were considered thresholds between the mundane and the spiritual.

Building Notre-Dame was a feat both of labor and love. From its early construction, the first stonemasons and planners could only imagine how it would look to their ancestors some two hundred years later when it was finally completed. The local quarry workers, cart-loaders, or those who treaded the great mechanical wooden wheels to raise the stone walls, would never have seen a plan, but they would have seen their beloved cathedral slowly taking shape over the years.

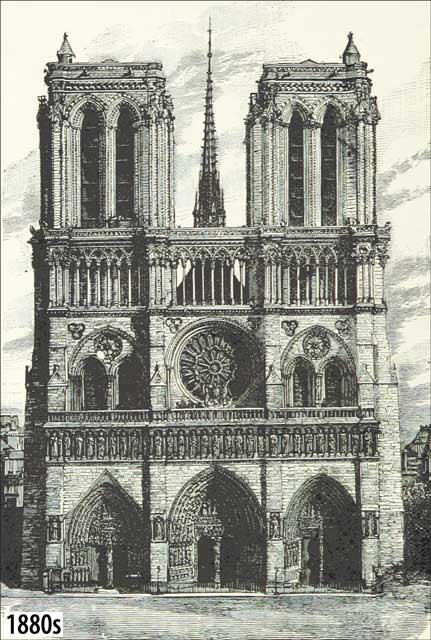

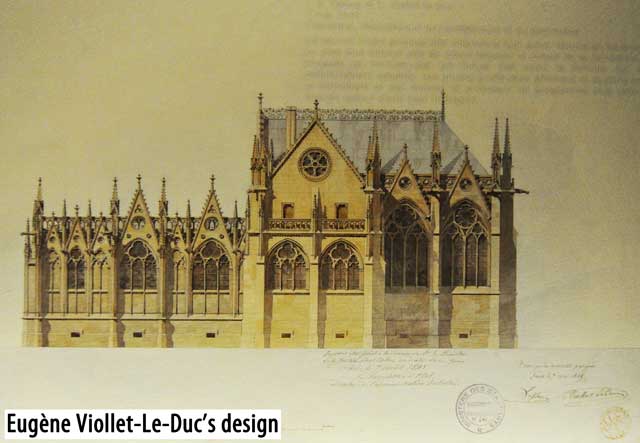

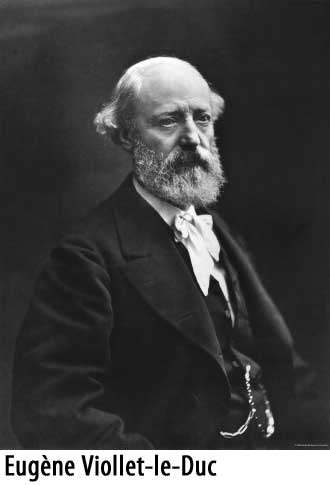

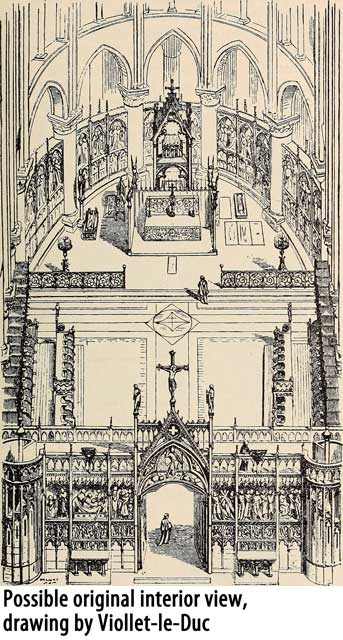

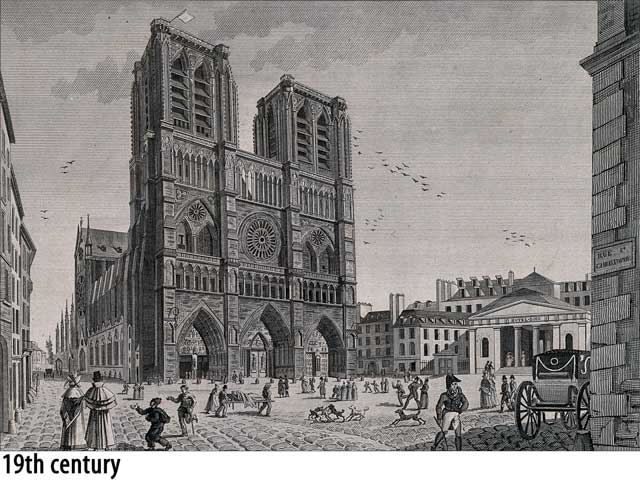

But what you see today is the architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc’s 19th century restoration of the Gothic dream of medieval Paris.

Let’s first admire the three magnificently carved portals, each dedicated to a specific Christian allegory.

Many of the original statues over the entrances were damaged in 1793, during the Revolution, when the cathedral was dedicated to le Culte de la Raison, the Cult of Reason, and later to le Culte de l'Être Suprême, the Cult of the Supreme Being. Lady Liberty replaced the Virgin Mary and for a few years the cathedral was used as a warehouse to store food.

The cults were banned and religion restored when Napoléon Bonaparte (Napoléon I) crowned himself emperor in 1804, here in Notre-Dame, beside his beloved Josephine.

The left portal is dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

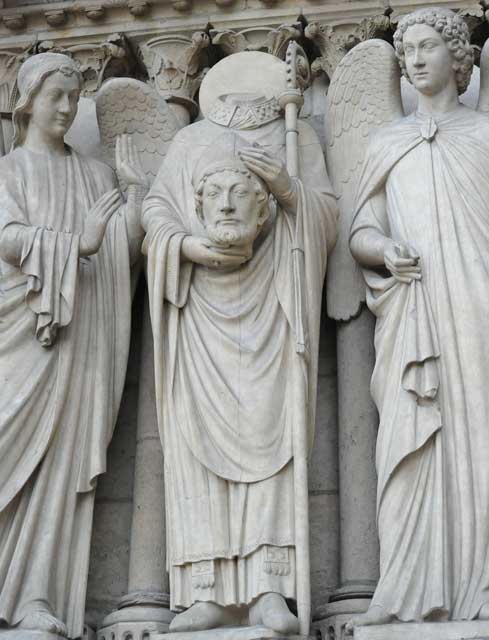

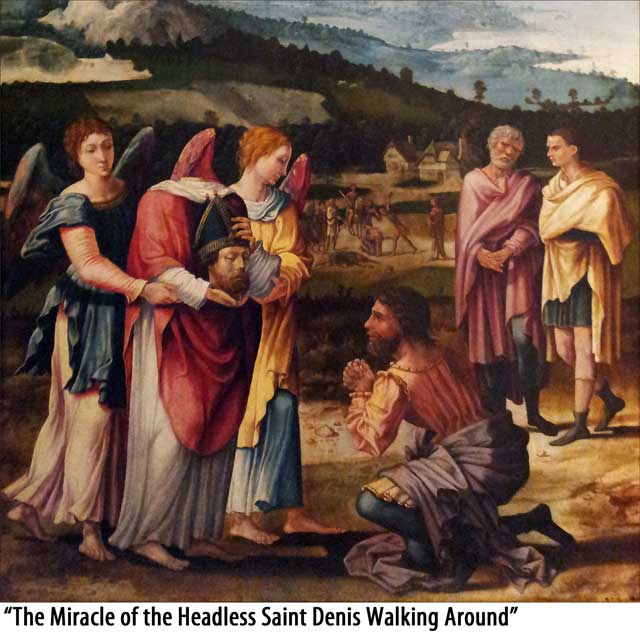

On the left side you can see four figures. Two are angels, and one appears to be a man holding his own head!

The early Roman settlers weren’t at all happy that the Christians were trying to convert them from their pagan beliefs. In fact, as a lesson to all those who preached Christianity throughout the city, Bishop Denis was beheaded along with several other martyrs up on the so-called “hill of martyrs,” now known as Montmartre.

Legend tells that Denis wasn’t quite ready to meet his maker. He picked up his head and tucked it under his arm. Walking for several kilometers (or miles) around Paris, he washed the blood from his head in the Seine River and proved the miracle of his Christian faith, before he collapsed and died.

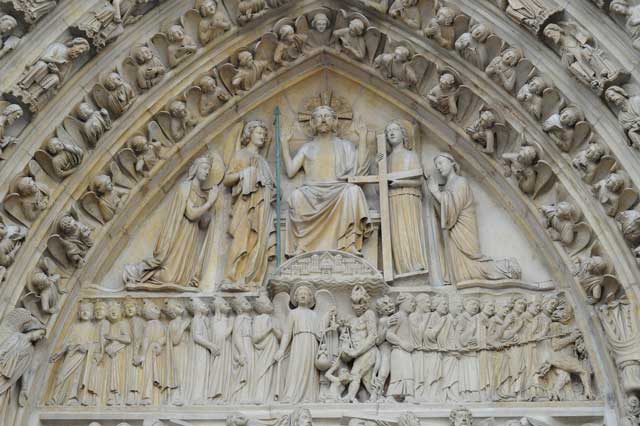

The middle portal shows scenes from the Last Judgment.

The dead are being revived, their souls weighed and judged. And then some souls are led by Christ to heaven.

And some are, alternatively, led by the devil to the right.

The right side is where hell is.

The right portal is dedicated to St. Anne, the mother of the Virgin Mary.

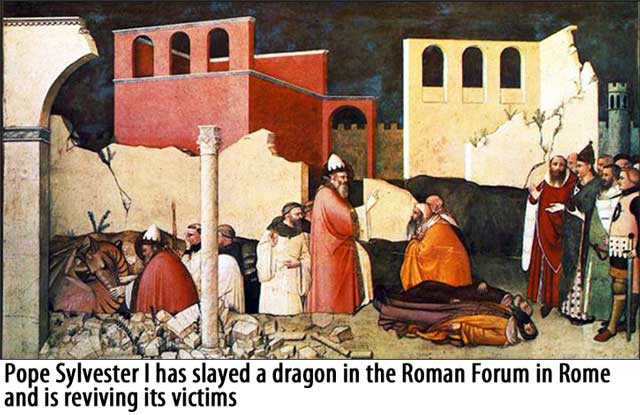

On the central pillar you can see a statue of St. Marcel, the 4th century bishop of Paris. Beneath his feet is a serpent. The original statue was destroyed in the Revolution, and it had an even more fearsome serpent and a less pious looking bishop.

A legend tells of how Marcel fought and eventually destroyed a great monster serpent living in the Seine River. The serpent had spent many nights hunting and eating the inhabitants of the city. Lying in wait for the serpent on the banks of the Seine, Marcel drank large quantities of wine to calm his nerves.

As the serpent arose from the muddy waters, he pushed his bishop’s scepter straight into the serpent’s mouth, poured the rest of the wine down its throat, destroyed the monster, and saved his people.

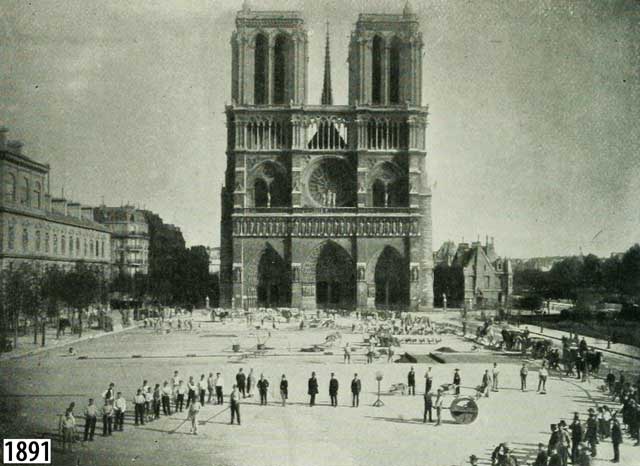

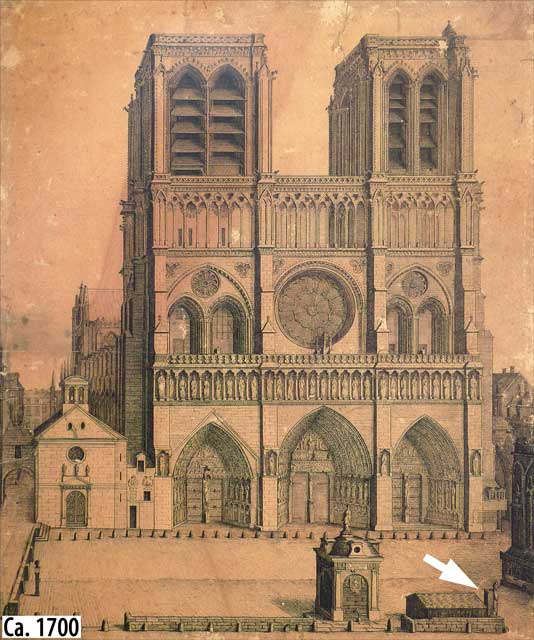

The Place du Parvis Notre-Dame, the square in front of Notre-Dame, is always full of people.

Most of them are queuing up for visiting the cathedral.

The Place du Parvis, meaning Paradise Square, was created in the 19th century to showcase Notre-Dame Cathedral.

But it wasn’t always such a light, airy, and open square.

In the past, the land here was crowded with tightly packed, polluted streets and alleys. These were all demolished over the centuries for the various reconstructions of Paris.

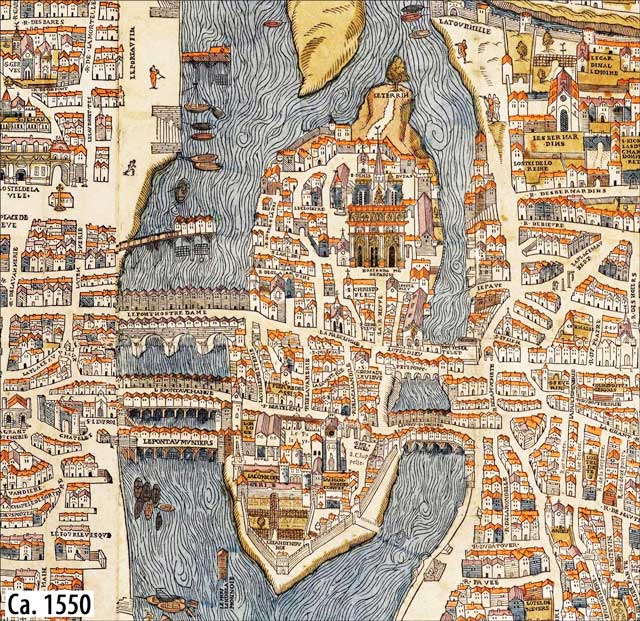

In medieval days, the new cathedral was surrounded by narrow courtyards, wooden houses, and gabled buildings dotted with chimneys and weather vanes. There were tiny shops, called échoppes, among the medieval tangle of timber-framed cottages packed together tightly like a deck of cards. The timber frame houses had carved beams and niches on each corner of the street where statues were placed of the Madonna or favored saints.

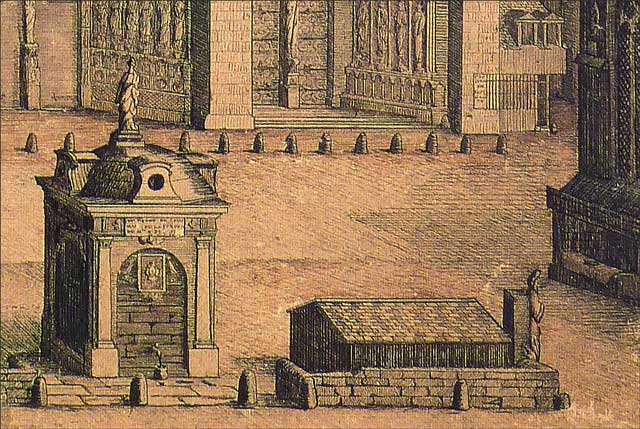

Before going inside and soaking up the atmosphere of Notre-Dame, let’s find the zero point, a marker in the square, which often gets overlooked by passing visitors.

Some 20 meters (66 feet) into the square from the cathedral’s central portal, there is a brass plaque in the paving stone.

Around the plaque is an inscription “POINT ZÉRO DES ROUTES DE FRANCE” (“the point zero of French routes”). Laid in 1924, it marks the point from which all distances in France are measured from the exact center of Paris, here. But one must not confuse this with the famous Arago medallions, which are aligned with the Paris meridian.

The point zero plaque is considered a lucky place to make a wish. Couples stand here to kiss, others dance under the full moon.

There’s also a belief that if you stand on this spot as a tourist, it means you’re going to come back to Paris again.

But there’s more to this marker than meets the eye. Until the 18th century, a mysterious statue stood at this very spot. The statue was of a man or god, holding a book and accompanied by a serpent, attached to a stone column.

No one knows when it first appeared in the square, but it dated from the pre-Roman period. During the 12th and 13th centuries of medieval Paris, as the construction of Notre-Dame mounted stone by stone, people called the statue Monsieur Legris. The origin of the name is not clear, but le gris means gray. Most scholars believe it was because so many years of weather erosion and pollution had given the stone a gray appearance.

Over the years, the stone was so weathered that he was barely recognizable. The local people would jokingly tell pilgrims who were ever trying to find their way out of the web of streets that Monsieur Legris would show them the way and point to the disfigured statue.

Historians and scholars have suggested various identifications for the statue. Some say it was Hercules or Asclepius, the Greek god of medicine. Others suggest Jesus Christ, Guillaume de Paris, St. Geneviève, and perhaps most relevant of all, the Roman god of boundary stones and journey endings, Terminus. Another contender was Mercury, the god of travel and trade.

The statue was Hermes Trismegistus to the Hermeticists, an esoteric cult of the Renaissance. Hermes Trismegistus means three times great Hermes, and this divine figure had the answer to all that was known in the universe. The Hermeticists were rather like freemasons. They had a secret way of transferring their divine knowledge through symbols and alchemical metaphors.

Hermeticists were despised and treated as heretics by the Catholic Church. Through the centuries they included well-known initiates such as the astrologers and alchemists, John Dee and Robert Fludd, and later, the scientist, Sir Isaac Newton, poet W. B. Yeats, and a well-known alchemist, Flamel.

For alchemists, gray signified fire, one of the five elements and part of the alchemical process for achieving divine knowledge. Interestingly, the statue was later nicknamed “Maitre Pierre” or the “Master Stone” which also refers to the philosopher’s stone, the alchemist’s key to divine union.

When a fountain was erected next to the statue in 1625, an inscription in Latin on the statue read, translated, “Approach those of you who are altered, and if by chance my waters are not enough, go to the temple, and the goddess you invoke will prepare eternal waters for you.”

Curious though this inscription is, let’s try and put some facts together. Monsieur Legris was also known as “Vendeur des Jeunes” or “Seller of Fasts” where fast means to not eat. He was also known as “le Jeuneur” or “the Faster.” This inscription may be a simple Christian reminder of the need to fast and pray if you’re ever going to get close to the holy waters of God. Another explanation was that it is time to go into the cathedral and devote yourself to the Virgin Mary. But yet, as the Latin word diva in the inscription means goddess, it is suggesting a pagan link behind this mystery. The Virgin Mary was hardly considered a goddess or diva by the Romans, who worshipped Cybele and Maia long before the Christians worshipped Mary.

Whatever the case, the mysterious Monsieur Legris is here no more, but in a way he pointed out to the pilgrims back then, and maybe to us now, that there may be more to the visit to Notre-Dame than just going in and then coming out.

A satirical pamphlet published in 1649 by the anti-Royalists, when the young Louis XIV was under the politically corrupt wing of Cardinal Mazarin, was entitled “An Oracle Given by the Faster of Notre-Dame” and which listed all the remedies needed to “cure” the country of its cardinals and kings. Maybe this statue has always been an oracle for messages from the gods?

Sadly the Monsieur Legris statue was removed and destroyed in 1748, when it was decided to enlarge the square and demolish many of the houses. It was replaced by a triangular marker with the emblem of Notre-Dame at its center. At the time, during the on-going war of Austrian succession, it became the zero point for measuring distances to the network of military outposts and camps along a series of milestones, approximately every two kilometers (1.2 miles), from this central point of Paris. It has continued in that tradition up to today. Yet, maybe Monsieur Legris had always been there to point the way to anywhere in the universe?

The space in front of Notre-Dame was at one time also the scene of many executions. For instance, in 1587, under the reign of King Henry IV, Dominique Miraille, an Italian, and the Lady of Étampes, his mother-in-law, were condemned to be hanged and afterward burned in front of Notre-Dame for the crime of magic.

The Parisians at the time were astonished at the execution and one of them wrote in his journal, “…for this sort of vermin have always remained free and without punishment, especially at the court, where those who dabble in magic are called philosophers and astrologers.”

These days, instead of horrible executions, during Christmas time the square hosts the traditional Christmas tree.

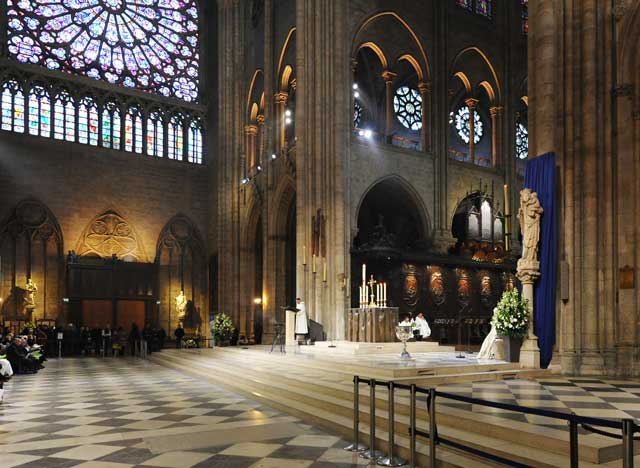

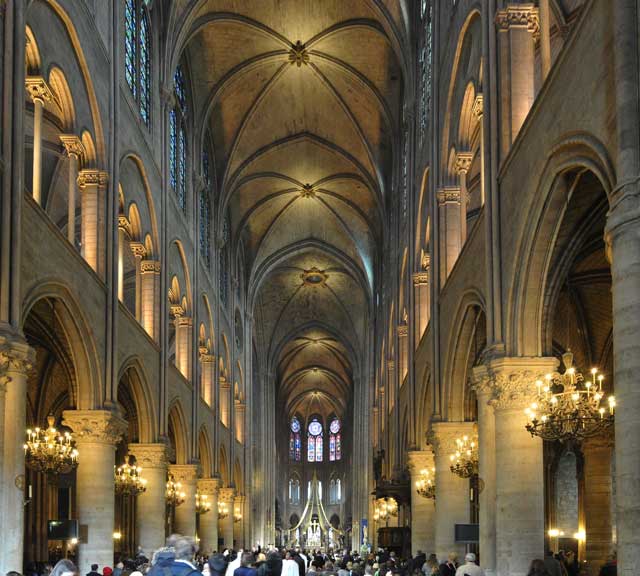

Standing in the middle of the central nave facing the choir in the distance you get a good look at the impressive interior of the cathedral, which is 130 meters (427 feet) long and 48 meters (157 feet) wide. You can take in the majesty of the building, its stained glass windows, its perfect symmetry.

And above is an enormous vaulted ceiling, 35 meters (115 feet) high.

Its history and extraordinary architecture are one thing, but you may feel a little emotional in such beautiful surroundings too.

Notre-Dame remains an active Catholic church.

There are different religious services held daily.

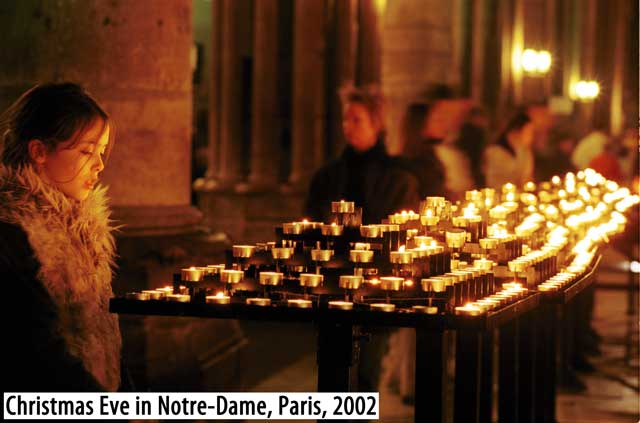

As is usual with Catholic churches, there are more worshippers attending the Masses on Sundays and during Christmas and Easter.

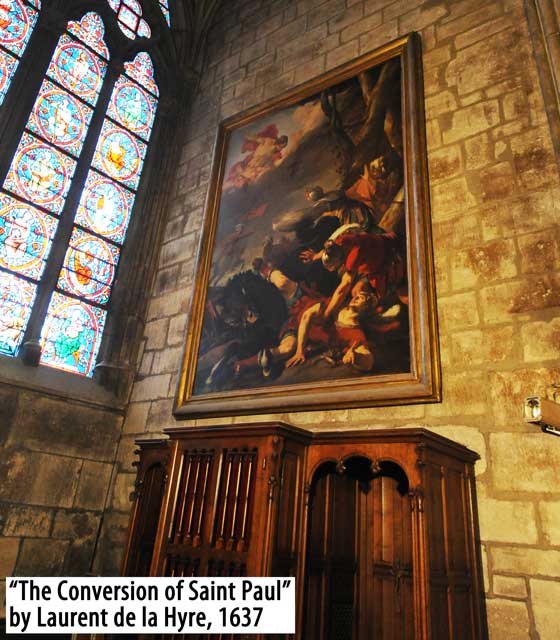

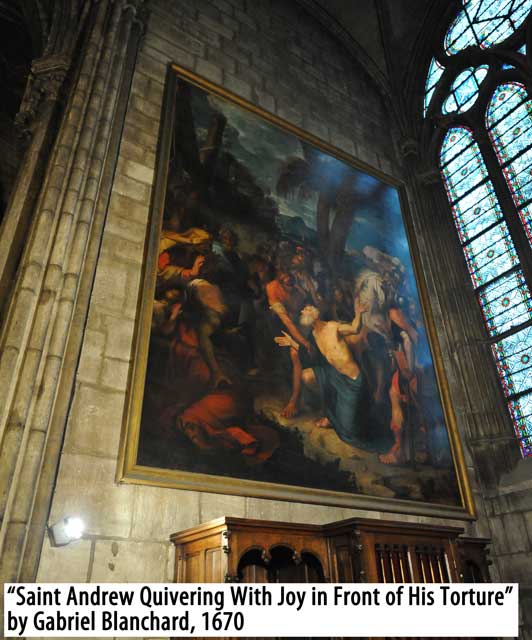

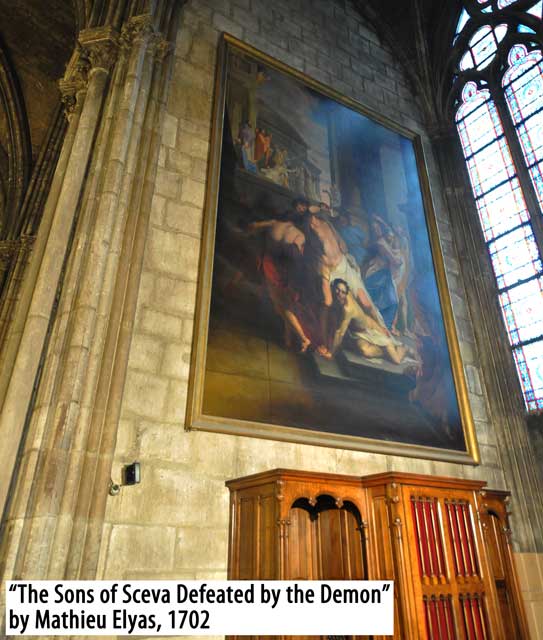

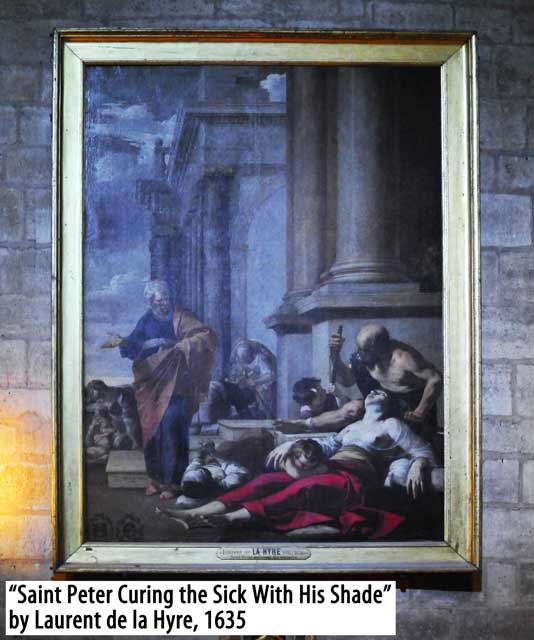

In the chapels in the outer isles are displayed the so-called Mays of Notre-Dame. These are huge oil paintings, like “The Conversion of Saint Paul” painted by Laurent de la Hyre, which was donated to Notre-Dame in 1637 and is now in one of the first chapels on the right dedicated to St. Anne, the mother of the Virgin Mary.

The Goldsmith’s Guild of Paris started a tradition of donating gifts to the cathedral on the first day of May, in honor of the Virgin Mary, in 1449.

This tradition took on various forms over the centuries. In the beginning it was simply a young green tree, decorated with banners and ribbons and placed in front of the cathedral’s High Altar, representing new growth and the birth of Jesus. As the years went by, the May gifts became more elaborate and works of art or poetry were placed in golden caskets or hung from jewel-encrusted sacred boxes. By the 16th century small depictions of scenes from the Old Testament were included too.

From 1630 until 1708, large oil paintings, three or more meters (10 or more feet) high, were donated as Mays.

In 1793, the Revolution seized the paintings and they were either hidden away, lost, or destroyed.

During the Revolution, much of gold or silver treasures in France were melted down, and the goldsmiths, wisely, like many others, went underground in an attempt to dissociate themselves from the Church or royalty.

After the restoration of the monarchy, the Goldsmith’s Guild reformed and was favored by Napoléon I and particularly by Napoléon III who commissioned many of the gold vessels found in the Notre-Dame treasury today. Many Mays were found and distributed to museums in Paris, including the Louvre. Thirteen are now on permanent display in Notre-Dame.

In 1949, the guild gave Notre-Dame a green tree as a reminder of the first May offering, as well as an exquisite silver and gold goblet which is kept in the cathedral’s treasury.

Very few people, mostly members of royalty, archdeacons, archbishops, and generals, have been buried in the cathedral. For instance Queen Isabelle of France, the wife of Phillip II, who died in 1190; the 12th century Geoffrey II, the son of Henry II, King of England; and the 16th century French poet, Joachim du Bellay, who probably got his plot inside the cathedral because he had once been a Notre-Dame canon. Also the heart of the mother of Francis I, the 16th century Louise of Savoy, was once entombed in a crypt below the High Altar in a lead box under a copper tomb.

During restoration work in the middle of the 19th century, most of the tombs were moved to the central choir crypt, below the marble floor. Some tombs are also in the chapels around the nave.

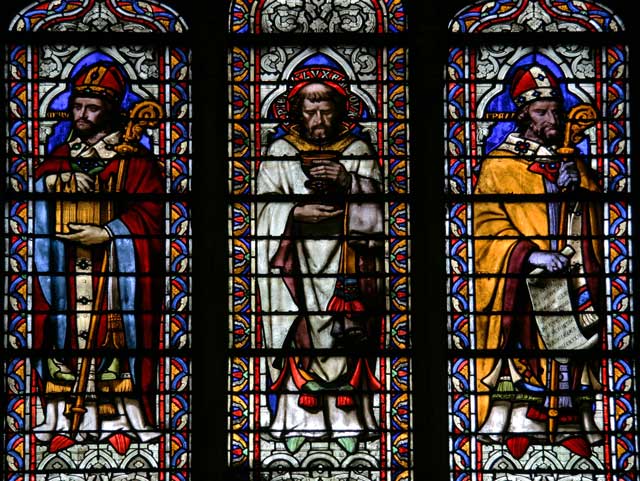

Throughout the cathedral there are many beautiful stained glass windows, varying in size and shape.

They are works of art by themselves and well worth taking some time to look at.

Besides the daily religious services many grand events and even theatrical performances have taken place in Notre-Dame during the many centuries.

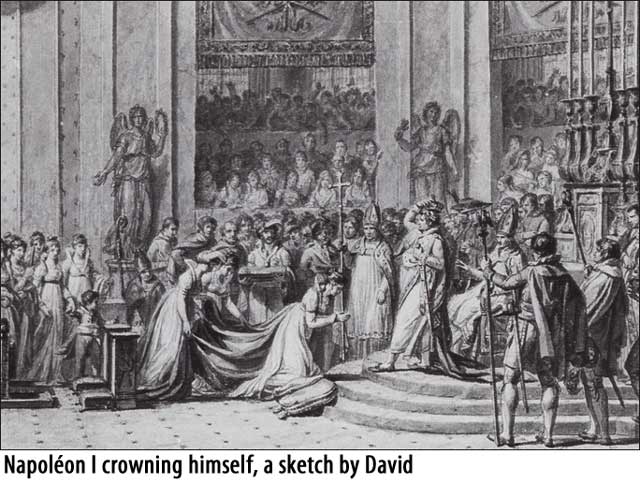

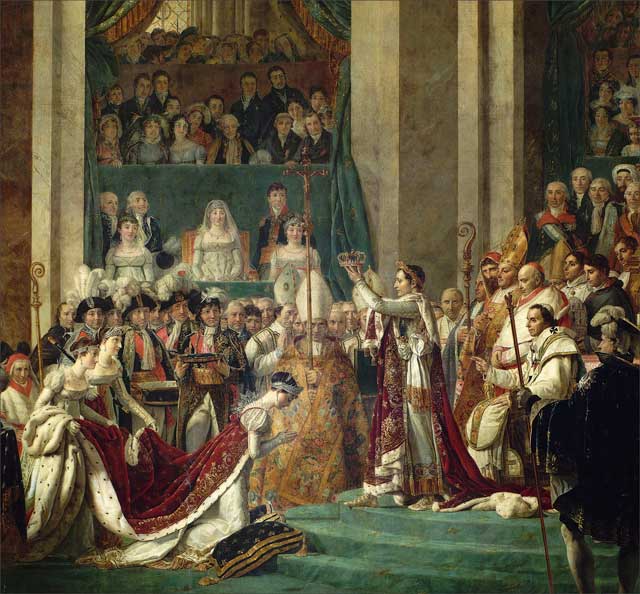

Probably the most imposing ceremony ever witnessed within the walls of Notre-Dame was the coronation of Napoléon Bonaparte (Napoléon I) on Sunday, December 2, 1804.

The artist, Jacques-Louis David, has depicted this event on his famous painting, commissioned by Napoléon I himself.

The whole event was pompous and started when Pope Pius VII set out with his entourage at 10 a.m., much earlier than the emperor, in order that the ecclesiastical and royal processions should not clash. The pope was accompanied by numerous clergy, gorgeously attired and ornamented, whilst his escort consisted of detachments of the Imperial Guard.

When the pope entered the cathedral, there were assembled the deputies of the towns, the representatives of the magistracy and the army, numerous bishops with their clergy, members of the Senate, the Council of State, and the representatives of the different European powers. When the pope, preceded by the cross and by the insignia of his office, appeared, the whole assembly rose from their seats, and five hundred instrumentalists and vocalists gave forth with sublime effect the sacred chant “Tu es Petrus.” The pope walked slowly toward the altar, before which he knelt, and then took his place on a throne that had been prepared for him to the right of the altar. The 60 prelates of the French Church presented themselves in succession to salute him, and the arrival of the imperial family began.

The cathedral was magnificently decorated. At the foot of the altar stood two plain armchairs which the emperor and empress were to occupy before the ceremony of crowning. The central door of Notre-Dame was closed, because the back of the imperial throne was placed against it, just opposite the altar, raised upon a staircase of 24 steps and placed between imposing columns, on which the emperor and empress were to seat themselves when crowned.

The emperor did not arrive until considerably late and the position of the pope was a painful one during this long delay. The emperor arrived in a carriage which seemed entirely made of glass and bearing a crown. He wore a plumed hat and a short mantle. He was not to assume the imperial robes until he had entered the cathedral. Escorted by his marshals on horseback, he advanced slowly amidst the acclamations of immense crowds, delighted to see their favorite general at last invested with imperial power. On reaching the cathedral, Napoléon I stepped out from his carriage and walked. Beside him was borne the grand crown, in the form of a tiara, modeled after that of Charlemagne (Charles the Great or Charles I), the king of the Franks. Up to this point Napoléon I had worn only the crown of the Caesars – a simple golden laurel. Having entered the church to the sound of solemn music, he knelt, and then passed on to the chair which he was to occupy before taking possession of the throne.

The ceremony then began. The scepter, the sword, and the imperial robe had been placed on the altar. The pope anointed the emperor on the forehead, the arms, and the hands; then blessed the sword, which he then put on Napoléon I, and the scepter, which he placed in Napoléon I’s hand; and finally started to take up the crown.

Napoléon I, however, then seized the crown from the pope and crowned himself.

Next, he took the crown of the empress, approached Josephine, and as she knelt before him, placed it with visible tenderness upon her head, whereupon she burst into tears.

Napoléon I next proceeded toward the grand throne, and, as he ascended it, was followed by his brothers, bearing the train of his robe. Then the pope, according to custom, advanced to the foot of the throne to bless the new sovereign and to chant the very words which greeted Charlemagne in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome in 800, when the Roman clergy proclaimed him Emperor of the Romans, “Vivat in æternum semper Augustus!” At this chant shouts of “Vive l’empereur! – Long live the emperor!” resounded through the arches of Notre-Dame, while the thunder of cannon announced to all Paris the solemn moment of Napoléon I’s consecration.

The painting took David more than two years to finish. When Napoléon I went to see the finished version, he said to the painter, “Very good, very good indeed, David. You have exactly seized my idea. You have made me a French knight. I am obliged to you for transmitting to future ages the proof of an affection I wished to give to her who shares with me the responsibilities of government.”

David had originally represented Pope Pius VII with his hands on the knees, as if taking no part in the solemn scene. Napoléon I, however, insisted on the painter giving the pope a more active pose saying, “I did not bring him here from such a distance to do nothing!”

It is said that when the picture was exhibited a critic pointed out to David that he had made the empress younger and prettier than she really was. “Go and tell her so!” was the reply.

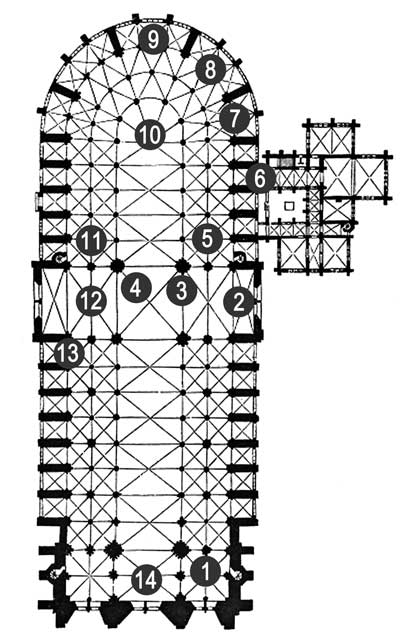

Let’s now take a tour of Notre-Dame, around the outer aisle, starting from the right (No. 1 on the plan of the cathedral).

Lined along the walls are various chapels dedicated to specific saints.

You can light a candle to your friends or family, or those you have lost, at any chapel of your choice as you walk around.

The point where the transept crosses the nave symbolizes the right angle of the cross of Jesus (No. 2).

Here you can see a beautiful statue of the famous Jeanne d’Arc (Joan of Arc).

Jeanne d’Arc has been honored as a political heroine. She has also become a symbol of female valor and courage.

Born to a poor family in 1412, Jeanne first heard an angel’s voice in her father’s garden when she was a child. Her spiritual and military crusade, toward the end of the Hundred Years’ War between England and France, had a long-lasting influence on the political destiny of the period. The war was a succession dispute between royal families, which lasted nearly one hundred years, culminating in 1437, not long after Jeanne’s tragic death in 1431.

King Henry V of England had invaded northern France and won the Battle of Agincourt in 1415. When Jeanne received her visions her hometown, Orleans, was under siege by the English. Whether through God’s messages or pure luck, Jeanne’s campaign tactics against the English worked and the siege of Orleans was lifted. Her further crusades were also successful, she helped defeat the English in Reims and Troyes. Jeanne’s campaigns continued, but her luck ran out. She was captured and sold to the English for 10,000 livres, equivalent to around $100,000 of today.

Under the tricks and lies of the corrupt Inquisition, led by the vengeful Bishop Cauchon, her trial was a mockery. Her clothing was the one thing that the ingenious Cauchon eventually used as his main prosecution weapon. While campaigning and in battle or on horseback, Jeanne had worn men’s clothes or dressed in armor to protect herself from battle wounds, but also from the lecherous advances of most of the frustrated male army. Her apparent refusal to wear female attire gave Cauchon the chance to convict her of the “cross-dressing” charge, and pronounced her a heretic. She was condemned to death and burned at the stake. Her Paris allies demonstrated against her unlawful fate in front of Notre-Dame, but it wasn’t until the English were driven from Rouen in 1449, 18 years later, that an appeal was made and she was given a posthumous acquittal. It was declared that she had been convicted by a corrupt court, itself a heresy against the Catholic Church. Cauchon was denounced, and Jeanne was elevated to martyrdom status.

However, it was only in 1909 that she was sanctified here in the cathedral, and it wasn’t until 1920 that she was finally given sainthood by the Catholic Church.

The other statue here is of St. Thérèse d’Avila. She never fought battles, nor did she change the course of political history, but she did revive a cult of mystical spirituality in the Catholic Church.

Thérèse was born in Avila near Madrid in Spain, in 1515. She ran away from home when she was a little girl in attempt to martyr herself in the hands of the bloodthirsty Moors at war with the Spanish. She was stopped in time and sent to a nunnery where it was thought she would be safe. Like many other mystics in history, she began to suffer from nutritional problems, denying herself food or drink to prove her love for Jesus. She wrote of many visions and mystical experiences, known as ecstasies, the term coming from a Greek word that means standing outside oneself.

In her writings, Thérèse recounts how she saw an angel, not very tall, marvelous and beautiful. In his hand the angel held a long golden spear, with a flame of fire. He thrust the burning spear into her, sometimes in her heart, at others into her belly, and as he drew out the spear, it felt as if he was drawing out her entrails. But at the same time, she was filled with the fire and love of God. The pain was so intense that she moaned and cried out, but because it was such an exquisite pain, she wanted it to go on forever. Whatever kind of mystical or physical experience Thérèse was recalling, her passion hit the right chord and the Catholic Church embraced this mystical approach to prayer and devotion.

But whether Jeanne d’Arc’s visions were real, or Sainte Thérèse’s ecstasies were true, both women were still only human beings. So perhaps, just like the goddesses, divas, or the Virgin Mary, they are also the true notre dames or our ladies of this cathedral.

Next to the pillar you can see the statue of the Virgin Mary holding the infant Jesus (No. 3), known as Notre-Dame de Paris (Our Lady of Paris).

Notre-Dame Cathedral is so called in honor of the Virgin Mary, Our Lady. There are over 30 statues of Mary throughout the cathedral, but this is the location where a statue of the Virgin was placed at the end of the 12th century. Sadly, the original statue was destroyed in the Revolution in 1793. This replacement was actually sculpted in the 14th century, and came from the close-by Chapelle Saint Aignan.

Chapelle Saint Aignan, once part of the canon’s cloisters, was founded in 1116 by Étienne de Garlande, an archdeacon of Notre-Dame and chancellor to Louis VI. The statue was taken from there in 1818 and placed on the facade of Notre-Dame, on the central pillar of the Portal of the Virgin. Then in 1855, when the great restoration of the cathedral’s Gothic glory took place, it was finally moved to this key spot.

Strangely, you can see Mary not smiling, but sad, as if she knows the fate that will await her child.

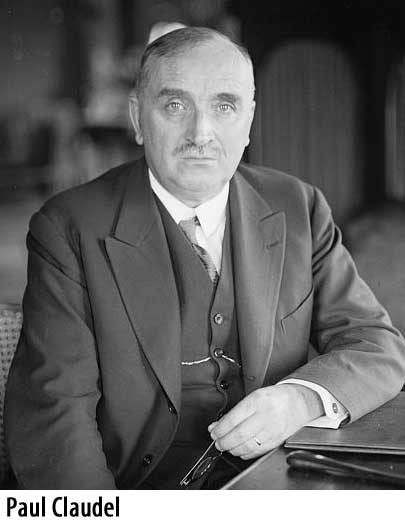

It was also here, exactly beside this same pillar, that the French writer, poet, and diplomat Paul Claudel stood on a cold, winter’s day and where he had a revelation, which would change his life forever.

Born in Paris in 1868, Paul Claudel was the brother of Camille Claudel, the talented but tragic sculptor. Despite being brought up as a Catholic, Paul refused to believe in God and hated his family’s religious faith. But when Paul was 18, he reluctantly joined in the Christmas celebrations outside the cathedral. He recalls how he was fairly skeptical about the whole affair, pushed around by the crowd and with nothing much better to do, he entered the cathedral to see what all the fuss was about. For a while, he enjoyed listening to the children singing in the choir.

Standing exactly here, by this pillar, he was suddenly overcome by a powerful force, as if he had been touched by something divine, and at that moment he believed in God. He was so overwhelmed by this force and this belief, that it changed his life, his convictions, and his goals forever. Claudel became a devout Catholic and wanted to enter a Benedictine monastery. But for most of his life, when not writing his spiritually inspired poetry, he devoted himself to the Catholic faith and right-wing politics, while working as a French diplomat around the world.

Yet Claudel wasn’t all goodness and light as his amazing Christian revelation might suggest. It was Paul Claudel who along with his mother committed his sister, Camille, to a psychiatric hospital in 1913. Camille destroyed most of her own artistic work because of her failed love affair with the famous sculptor Rodin. It was true she had bouts of paranoia and was emotionally unstable; but she was considered a genius, and many of Rodin’s friends believed that Paul Claudel made sure she never left the hospital again because he was jealous of her extraordinary talent. He even refused anyone else to visit her except himself. She spent the next 30 years of her life there until her death.

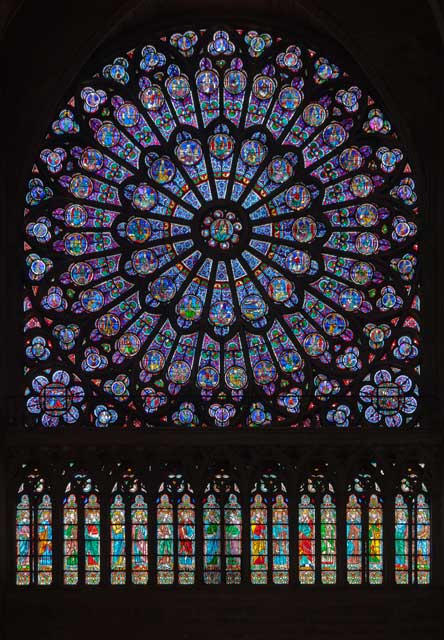

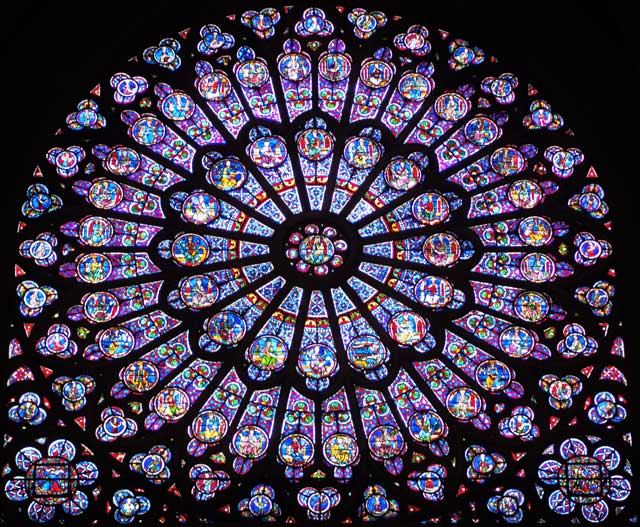

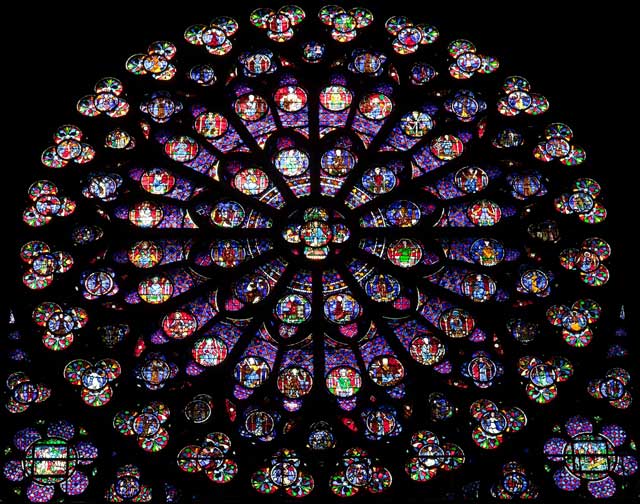

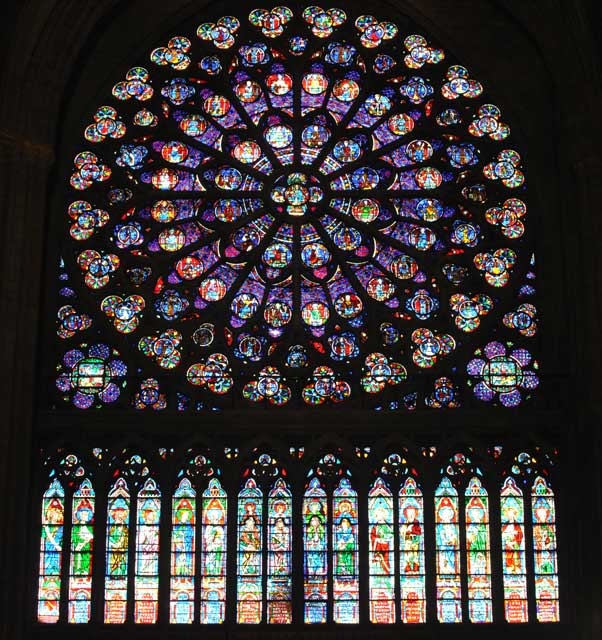

Across the nave, high above the doors, you can see the huge and magnificent North Rose Window, 13 meters (43 feet) in diameter.

The rose window features biblical figures from the Old Testament.

Different prophets, kings, and high priests surround the Virgin in the center.

The Virgin Mary is holding the infant Jesus Christ.

At the entrance to the choir, on a raised liturgical platform, you can see the modern altar (No. 4), a fabulous bronze chest crafted by sculptor and artist, Jean Touret. This altar is a recent work, consecrated by Cardinal Jean-Marie Lustiger on June 16, 1989.

The striking altar chest is decorated with the four apostles – Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, and the four great prophets from the Old Testament – Ezekiel, Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Daniel. The mystical number, four, and its multiples, is a recurring theme in Notre-Dame.

Jean Touret considered himself an artisan and has said, “As artisans, we invent nothing, we discover, we reveal. Life is encapsulated in the material we use, we have to respect it.”

Cardinal Lustiger has pointed out that the altar was placed in the center of the cathedral, at the exact crossing of the transept and nave, as a symbol of the mystery of the Eucharist.

The Eucharist is the consecration of bread and wine, representing the body and blood of Christ respectively. In the sacrament, meaning in that moment of administering the bread, known as the host, and the wine known as the chalice, a blessing is made.

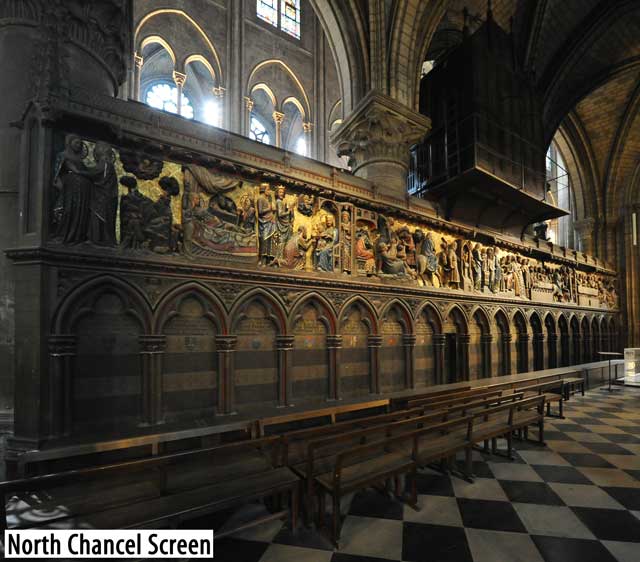

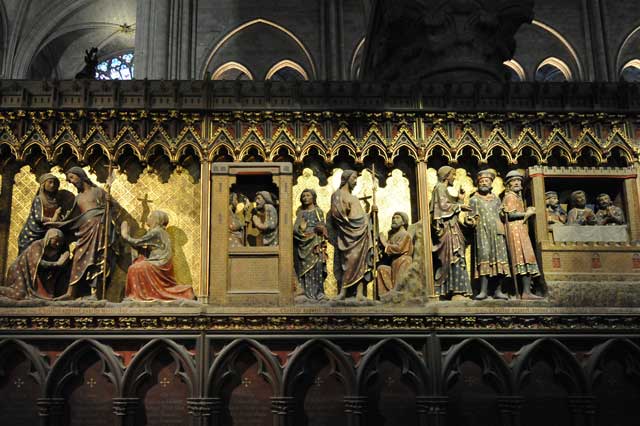

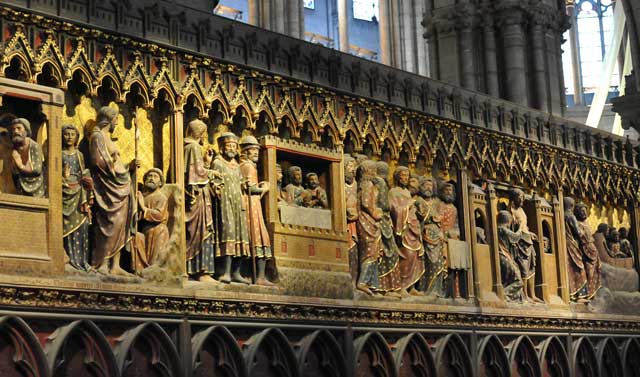

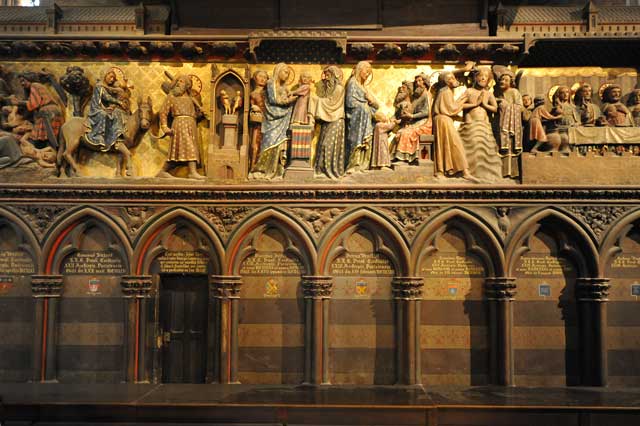

The South Chancel Screen (No. 5) is one of two surviving parts of a stone screen, which originally enclosed the chancel and provided canons at prayer with peace and solitude from noisy congregation.

From 1300 to 1350, three artists produced this set of nine panels with sculptures, depicting the appearances of the risen Christ.

The colors were repainted during the restoration work in the 19th century.

On the panels the risen Christ appears to Mary Magdalene, to the holy women, to Peter and John, to two disciples at Emmaus, to the Apostles, to Thomas, to the Apostles by the Sea of Tiberias, to the Apostles and disciples in Galilee, and on the day of Ascension.

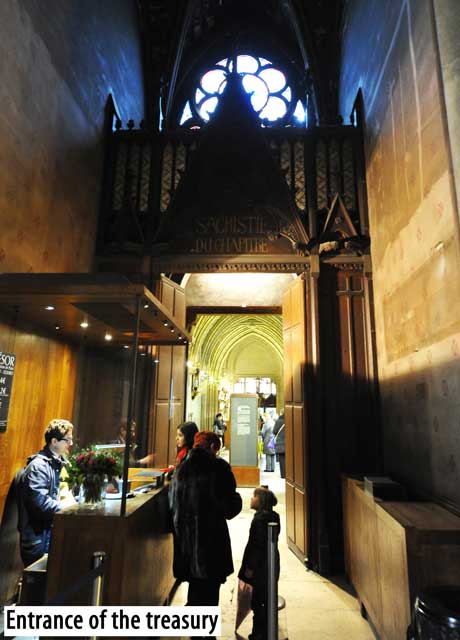

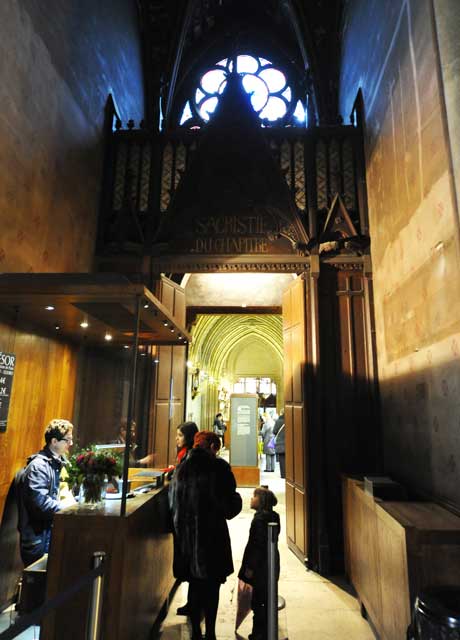

Next, you come to the entrance of the Notre-Dame treasury (No. 6), which is well worth a visit. If you decide to enter, then read this chapter about the treasury and what it contains.

Moving on, in the Chapel of St. Guillaume (No. 7) you can see the impressive mausoleum of Claude-Henry Harcourt, who was a Lieutenant General in the king’s army and died in 1769. He was one of a long family line of Harcourts, going back to the early Normans. This memorial was sculptured by the renowned French sculptor Pigalle in 1776.

An angel with a torch in one hand holds open the lid of the tomb with the other. Harcourt leans out, struggling to unwrap himself from his funeral shrouds as he reaches out to grasp the hand of his wife.

Lady Harcourt seems upset to be meeting her husband in this way, which is hardly surprising!

Entitled “Reunion Conjugal” or “Marriage Reunion,” Pigalle shows Death, the skeleton figure to the back of the tomb, holding up an hourglass. Death reminds the countess that the count’s time is up, and their next reunion will only be in eternity. The angel’s flame will be extinguished, and the tomb will close forever.

The chapel was restored in the late 1990s and is richly decorated with the letter “H,” the monogram of the Harcourt family.

Toward the end of the right nave is the Chapel of the Holy Sacrament (No. 8).

This chapel is reserved for meditation and prayer.

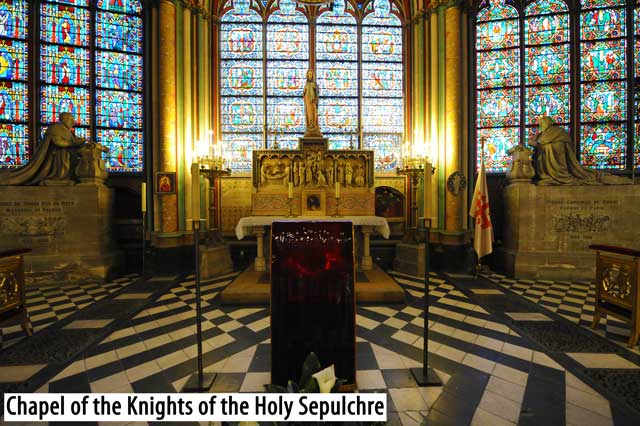

At the end of the nave is the Chapel of the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre (No. 9).

Here lays Notre-Dame’s most precious treasure – the holy Crown of Thorns.

It is impossible to state with any certainty that the crown is authentic, though its documented history dates back to the 4th century.

Behind, the altar is topped with a statue of Our Lady of Seven Sorrows, holding in her hands the nails and crown that wounded the feet, hands, and head of her son, Jesus Christ.

There are also three marvelous stained glass windows in this chapel.

On the right wall, there is a 14th century fresco depicting the Virgin and St. Nicaise, the former patron saint of the chapel.

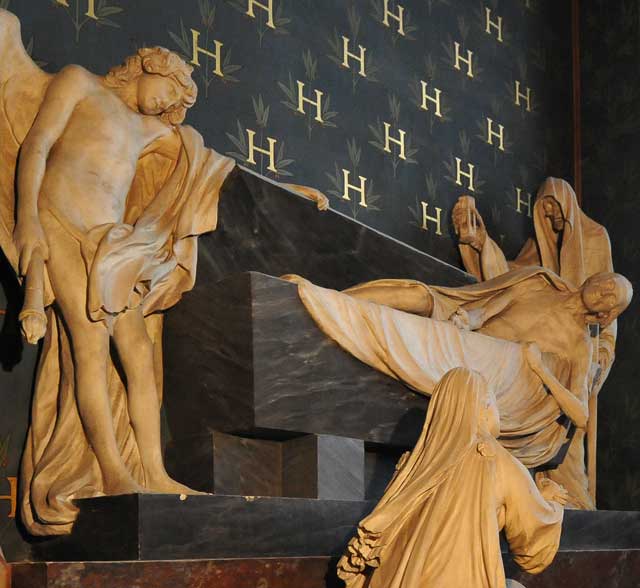

In the center of the choir area is the magnificent “Pietà” (No. 10), a sculpture depicting the Virgin Mary holding her dead son Jesus Christ, down from the Cross after the crucifixion.

After King Louis XIII’s long-awaited son, the later Louis XIV, was born in 1638, the king, in his gratitude to God, pledged to reconstruct the High Altar of Notre-Dame. But he died before carrying his vow into effect, and Louis XIV undertook to accomplish it for him some 50 years later. It was a huge project that lasted until 1708 and during which the architects destroyed the Gothic choir and built a new choir in baroque style.

On a gilded base is the Virgin Mary, dead Jesus on her lap, raising her eyes to heaven with confidence. She is both sad and expectant at the same time, as remembering the promise of resurrection that was made to him.

On the right, King Louis XIII offers Mary his crown and scepter.

On the left, King Louis XIV is kneeling.

Behind, in front of the columns, six bronze angels carry the instruments of the Passion of Christ.

The choir stalls are decorated with beautiful carvings.

These date from the same reconstruction project of the 14th and 15th centuries.

The carvings depict, mostly, the scenes from the life of the Virgin Mary.

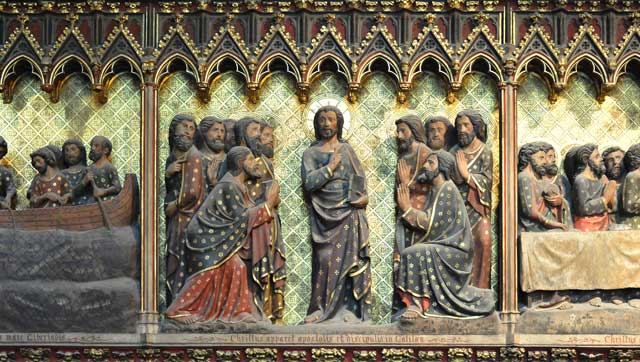

Next, you come to the North Chancel Screen (No. 11).

It was made together with the South Chancel Screen in the 14th century.

Its sculpted scenes continue from the southern screen and depict the accounts in the four gospels of the New Testament.

The colors were repainted by Viollet-le-Duc during the major restoration work in the 19th century.

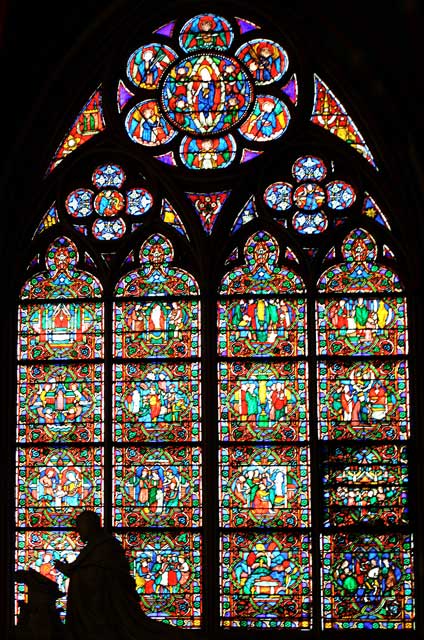

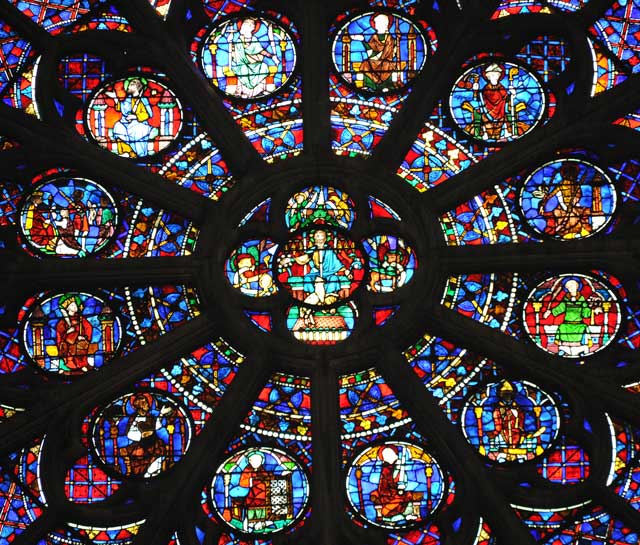

Back in the transept you can look across to the South Rose Window (No. 12), the best known of Notre-Dame’s windows.

The light streams beautifully down through the stained glass.

The South Rose Window was made to complement its opposite, the northern window, which was constructed earlier. King Louis IX, canonized as St. Louis, commissioned the South Rose Window as a gift to the cathedral and the designer Jean de Chelles completed it in 1260.

This window is made up of multiples of four. There are 84 panes, and each pane is divided into four circles. Then the math gets complicated. There are 12 medallions in the first circle, the second has 24, and then we get to even more intricate multiples of 24 and 48 with smaller panels of glass.

The number four is an important symbolic number in Christianity, both its earlier Hebrew association with the Greek word tetragammatron, meaning four letter word and referring to YHWH, or God, and in the Bible with the four great prophets of the Old Testament, and the four evangelists of the New Testament. In the biblical Book of Revelations, there are four angels standing at the four corners of the earth, holding the four winds of the heavens.

And then four’s multiple 12, with the 12 apostles at the Last Supper, and the 12 signs of the zodiac and so on.

Originally the window was dedicated to the New Testament, and the 12 apostles made up the 12 points of the first inner circle.

After problems with stonework of the surrounding wall in the 16th century, the window was propped up on wooden poles until 1725, when it was restored by glassmaker Guillaume Brice. But the workmanship was not up to standard, and it began to collapse again after a fire in the bishopric during the 1831 uprising. It was not until 1861 that work began again. Viollet-le-Duc was given the task. But the stonework restoration took up so much time that Alfred Gérente, the glass restorer, never quite got the hang of where to place the apostles and the other main characters. The 12 apostles are now jumbled in with the other figures in the inner circles, where martyrs, saints, and virgins all rival for the best bit of stained glass to shine their light.

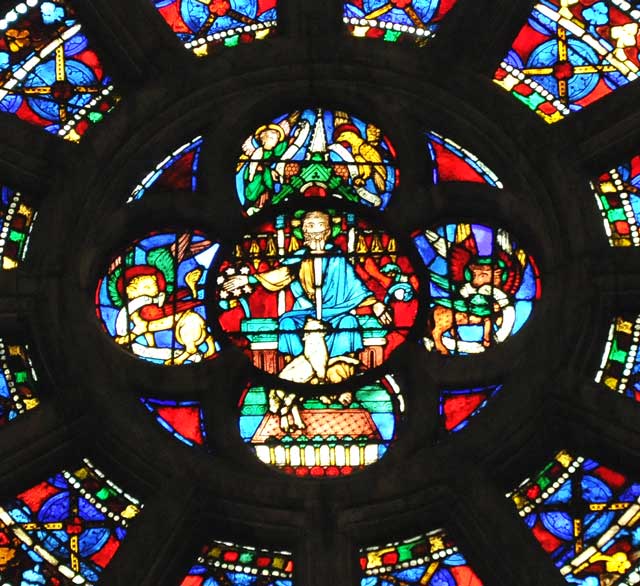

The central rose medallion depicts Christ of the Apocalypse, with the sword of truth ejected from his mouth and the stars shining on his wounded hand.

Inspired by a window in Chartres Cathedral, Viollet-le-Duc designed the heavenly court below.

With its 16 prophets lined up in a row like a line of dolls below the rosette, the four great prophets of the Old Testament: Ezekiel, Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Daniel take center stage, and above them, in the rosette, are the four evangelists of the New Testament: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.

This was a rather neat way of linking the Old and New Testaments, as suggested by the Bishop of Chartres Bertrand himself, to show that even though the Christian evangelists saw the highest truths, it was only because they were elevated to that vision by the greatness of the prophets of old.

It is interesting to remember that originally, the window was commissioned to represent only the New Testament, yet the changing face of the Catholic Church in the 19th century was having to give way to not only its earlier origins but also the popular culture of the time which looked beyond traditional religion for profound answers.

Next, let’s take look at one of the chapels along the northern aisle, dedicated to St. Clotilde (No. 13).

Here you can see a wonderful, stark but impressive funeral stone of the little known canon of Paris and Rouen, Canon Yver, sculpted in 1468 just after his death.

Yver, crippled by gout and gravely ill, limped into Notre-Dame during an election of a new archbishop for Rouen. Surrounded by 43 priests, archdeacons, and other canons, Yver managed to sign a procuration for Canon Duquesnay to vote for him. He knew that with a lengthy election process, he would never live to vote himself. Remembered for his courage to secure a procuration to vote while on his deathbed, he was never to return to the cathedral again, except when carried in his coffin to be buried.

Take a look up, at the West Rose Window (No. 14), its view partly blocked by the organ. It is the oldest rose window in the cathedral, dating from 1220.

It depicts the Virgin Mary and scenes from ordinary life, with symbols of the zodiac and the labors of the months.

Under the window you can see Notre-Dame’s organ, one of the largest in the world, with five 56-note keyboards, 32-note pedal board, 113 stops, and 7,800 pipes.

And now, before going back outside, let’s take one last look back, at the impressive interior of the cathedral, the masterpiece of French Gothic and one of the most famous church buildings in the entire world.

2. Statues of Jeanne d’Arc and St. Thérèse d’Avila

3. Statue of the Virgin Mary, view of the North Rose Window

8. Chapel of the Holy Sacrament

9. Chapel of the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre

12. View of the South Rose Window

14. Organ and the West Rose Window

Let’s take a look at the precious items in the Notre-Dame treasury, with an entrance inside the cathedral.

But the treasury itself is actually in a separate, attached building, which also houses sacristy rooms used by priests in charge of the church.

In the beginning of the 19th century, after many years of neglect, there was little left of the original building. It was entirely rebuilt between 1845-1850 following designs by architect Eugène Viollet-Le-Duc.

In the entrance corridor you can see Viollet-Le-Duc’s designs and various religious clothing items.

There are also beautiful stained glass windows, depicting the legend of the patron saint of Paris, St. Geneviève, whose legendary miracles saved Paris from the invading barbarians in the 5th century.

Over the centuries, most of the archival papers of Notre-Dame were destroyed and precious objects ransacked, especially during the Revolution of 1789-1799 and riots in 1830 and 1831.

Some of the items on display are gifts and donations given by cardinals, bishops, churches, and wealthy benefactors. There are also artifacts moved here from other churches for safety.

You can see beautiful cups, goblets, shrines, plates, and ostensoirs – special receptacles for carrying the Eucharist, which is the consecration of bread and wine, representing the body and blood of Jesus Christ respectively.

The most important items on display include the shrines made to house the holy relics of Christ.

In the Christian religion, the holy relics are believed to be the remains of various items connected to Jesus Christ’s legendary story. In medieval Europe relics were big business and they were highly sought after objects, boosting a kingdom’s wealth factor or improving its political connections.

King Louis IX, who lived in the 13th century, was a devout Catholic and benevolent crusader and wanted Paris to be the ultimate center of Christendom in Europe. Possessing the precious and highly prized relics would confirm that Paris was as powerful as Jerusalem.

At the time, politics and religion were inseparable, so it wasn’t surprising his addiction to shopping for relics was politically motivated. Unlike many other kings who went all out to steal or even fabricate false relics to prove their Christian power, Louis IX decided to simply buy them. So obsessed was he to out-relic the other kings of Europe, that he paid 135,000 livres for the highly sought after Crown of Thorns and a piece of the True Cross. This was more than double the cost of the construction of the Sainte-Chapelle chapel that he built to house the relics, and over half the yearly expenditure of the whole kingdom!

But he never achieved his one main goal: to conquer Jerusalem. His crusades proved to be the death of him, and he died of typhus fever in modern-day Tunisia.

Celebrated for his generosity to the poor, his devotion and humility, he was the only French king to be made a saint and was known affectionately as le roi chrétien, or Saint Louis, the Christian King.

Unfortunately, many relics – the fragments of the spear, nails, the Holy Cross, and the Crown of Thorns were destroyed, lost, stolen or hidden, during the Revolution in the 1790s. The open-sided golden coffer that held the Crown of Thorns was melted down. What remains of the relics is now preciously guarded in the Notre-Dame treasury.

The reliquary of the Crown of Thorns on display was commissioned in the late 1850s by Cardinal Morlot and Viollet-le-Duc was responsible for its design. It was to be an even more exquisite shrine for the Crown of Thorns than the one that had been designed in 1806 by Napoléon I’s goldsmith, Charles Cahier, in the neoclassical style. This version by Viollet-le-Duc made a statement that he was keen to stamp everywhere he went. Whether designing a cathedral spire or a lamp, he wanted the world to see that the culture of northern Europe wasn’t only rooted in the classical world but also in the Gothic.

On the reliquary you can see the dignified King Louis IX (St. Louis) holding the Crown of Thorns, St. Helen holding the True Cross, and Emperor Baldwin II of Constantinople with a scepter and globe in hand, looking rather smug, perhaps knowing how much money he would get from the deal when he sold the relics to Louis IX! The 12 apostles settle down in their niches.

A fleur-de-lis coronet is crowning the reliquary. Fleur-de-lis, a wild yellow iris, not a lily, became the royal French emblem in the 12th century. Considered to be originally a symbol for the rising sun and new growth, in the late 19th century it was used extensively in the decorative arts.

The upper part was designed to house the circular reliquary that encases the Crown of Thorns, which was woven of thorn branches and placed on Jesus Christ before his crucifixion.

Another very important item on display is the Cross of the Princess Palatine.

This superb golden double cross isn’t just a highly ornate gold cross but contains an important relic. Within the outer cross is a smaller cross which contains a fragment of wood, supposedly from the True Cross of Jesus, which can be seen in the mirror.

An inscription on the back of the small cross says that it belonged to the emperor of Trebizond in the 3rd century. Trebizond, which lay on the edge of the Black Sea, was once part of the Byzantine Empire. No doubt the small cross passed through a few rich royal hands, until in the 17th century, King John Casimir Vasa of Poland gave it to his sister-in-law, the Princess of Palatine, Anne Gonzaga.

Anne was born in Paris, into a line of prominent French and Italian families. Her ancestry was going back to kings of England and counts of Italy and the notorious Henri de Guise, instrumental in the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in Paris in 1572, when the Catholic League killed thousands of Protestants.

Before being miserably forced into marrying the penniless nobleman, Count Palatine, Anne had fallen madly in love with her cousin Henri, the later Duke of Guise. Flamboyant, heroic, and highly desirable, he was every woman’s romantic dream. This was enough for Anne to disguise herself as a man and travel to Sedan in Spain to win his love, but he rejected her even though she claimed they had been secretly married.

On her death in 1683, she donated the cross to the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in Paris. During the Revolution, the reliquary disappeared, but the small cross survived and in 1828 was put in the Notre-Dame treasury.

The lower part of this reliquary contains a small piece of the Nail of the Passion, with which Jesus Christ was crucified.

There is also another room here, with further displays of works of art.

On one side of this room there is a collection of carved portraits of popes.

You can also see some beautiful examples of pre-Revolution work of Parisian jewelers.

Towers and the Chimera Gallery

Before setting off on the visit to the towers, which are 69 meters (226 feet) high, you need to remember that there are 387 steps to climb (there is no elevator) upwards through a narrow spiral staircase.

If you’re prepared for the climb, it’s definitely worth it when you reach the top.

On a beautiful day you’re going to have a magnificent view of the whole of Paris.

Let’s first find out a little about the towers.

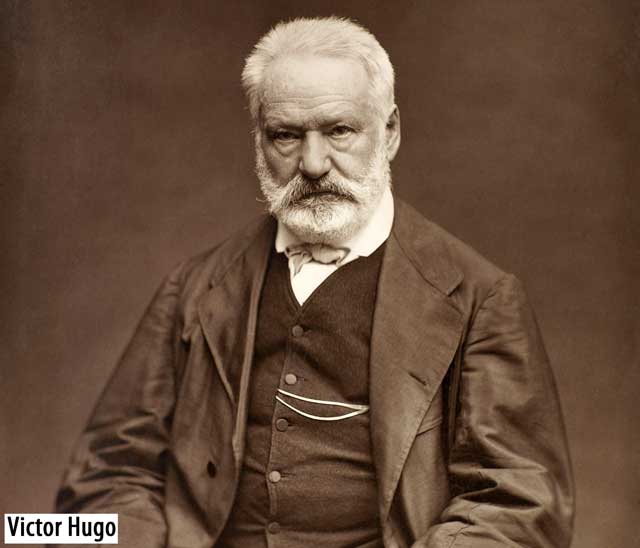

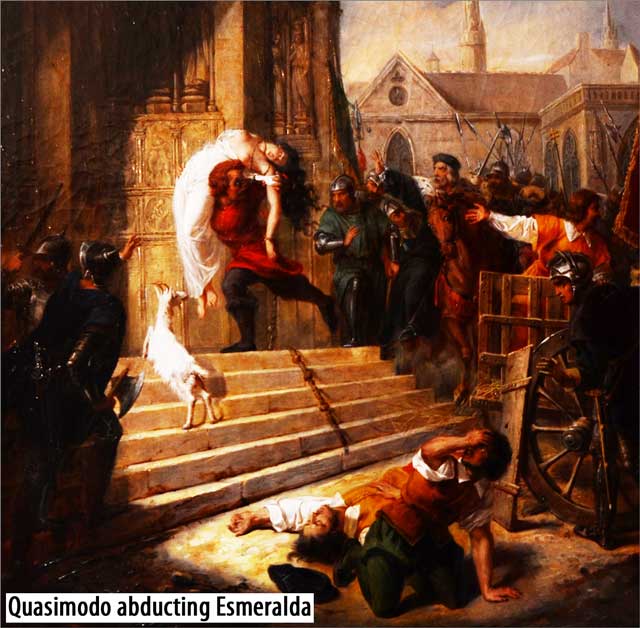

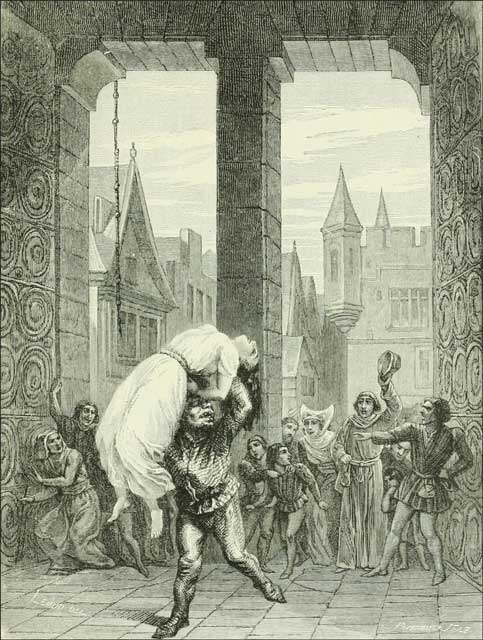

Of course, the most well-known story about the Notre-Dame towers was written by the 19th century writer, Victor Hugo. Quasimodo was the bell-ringer with a hunched back who fell in love with the gypsy dancer, Esmeralda. But why did these Gothic towers inspire Hugo to write a novel set against the backdrop of 15th century Paris?

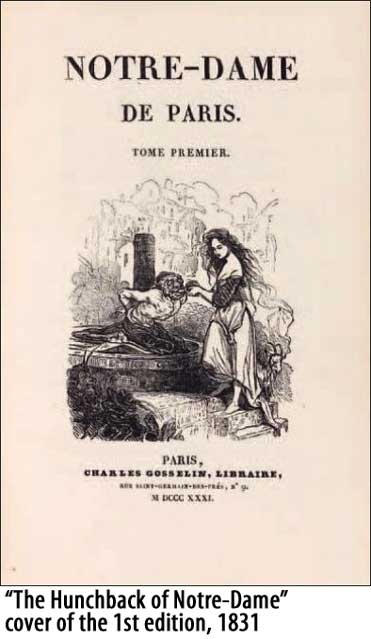

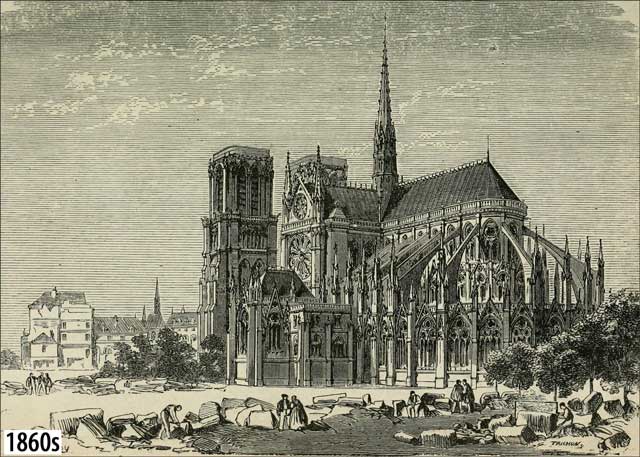

Published in 1831, Notre-Dame de Paris which is commonly known as The Hunchback of Notre Dame is a tale of fate, passion, melodrama, and morality. The popular success of this novel attracts as many visitors to Notre-Dame, as the cathedral’s religious and architectural heritage. And that is exactly why Hugo wrote the novel. In the wave of Romanticism that swept Europe in the mid-19th century, Hugo was one of the major protagonists for reviving France’s heritage, crusading for the restoration of many ancient monuments, which had fallen into disrepair after the Revolution.

Let’s try to remember Hugo’s melodramatic tale of the deaf bell-ringer Quasimodo’s unanswered love for a gypsy dancer, Esmeralda.

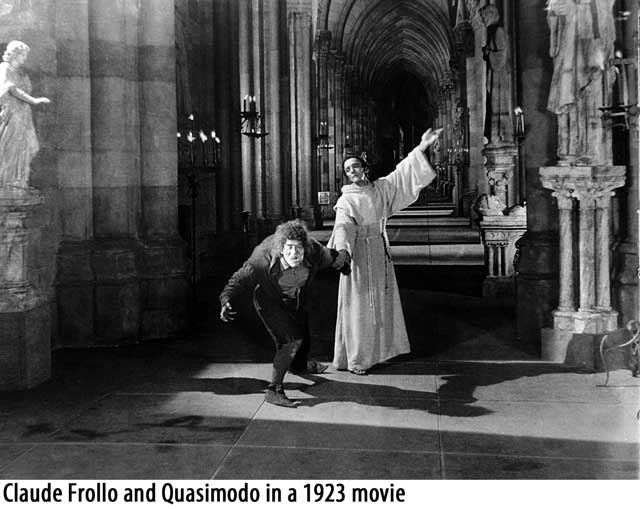

Long ago in the 15th century, Claude Frollo was a crooked archdeacon of Notre-Dame. He practiced medicine and alchemy, and many people feared he was a sorcerer. Torn between human lust and spiritual devotion, he was frustrated by his physical desires. When Esmeralda, a beautiful gypsy dancer, caught his eye in the street one day, his lust for her overcame any ascetic faith.

Yet 30 years earlier, Frollo had adopted the poor deformed Quasimodo who’d been abandoned as a baby on the steps of the cathedral. For all his dark despair and personal demons, Frollo wanted the best for the infant, but the child was ugly with a humped back and therefore socially unacceptable in 15th century Paris. So the lonely Quasimodo spent most of his life living in the confines of the cathedral.

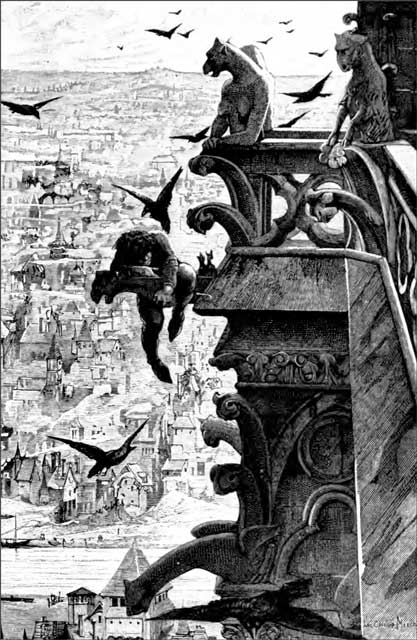

His only friends were the statues, chimera, and bells high on the cathedral towers. He laughed with them as they peered across Paris, and for all his strange deformity, he became as agile as a monkey among the bell ropes, spires, and statues. This was his real home, one where no one could reproach him. But the bell-ringing had made him deaf at a young age, and he could hardly speak.

As Esmeralda encouraged attention from desirable suitors, dancing in the streets around Notre-Dame, the more Frollo’s obsessive lust grew. One day, he attempted to seduce her, but she rejected his lustful advances and in his fury, he plotted for Quasimodo to kidnap her. But one of the king’s troops, Captain Phoebus, had also fallen in love with Esmeralda, and she with him.

One night, under orders from Frollo, Quasimodo attempted to abduct Esmeralda and take her to the cathedral, but Captain Phoebus and his troops arrived just in time to save her. Quasimodo was ordered to be whipped and tied to the pillory in the square in front of the cathedral. For a whole day, the public would spit on him or throw rotten vegetables at his face.

Quasimodo called for water, as best he could, and Esmeralda took pity on him and offered him a drink. It was then that he was instantly smitten with love for her.

Meanwhile, Frollo, his plot ruined by the intervention of Phoebus, vowed to put an end to their love affair. Cunning as a fox, he discovered their secret meeting place and stabbed Phoebus and framed Esmeralda for the attempted murder. Even Phoebus believed that Esmeralda had tried to murder him, and she was sentenced to be hanged. As she was led to the gallows, Quasimodo scrambled down the bell-rope of the tower.

He then snatched her away from the cart and took her into the sanctuary of the cathedral. One of her street performer friends, Clopin, thought she was in danger and he called on truants, the Paris criminals, to protect her. Frollo, enraged and jealous, asked the king to remove her right to sanctuary and to send in the troops to arrest her again. In the medieval period, anyone accused of a crime could seek the protection of the Church to avoid arrest. The rioting truants outside the cathedral alarmed the king, and he agreed to Frollo’s wishes. And so it was that the troops arrived, fought off the truants, and arrested Esmeralda. This time she could not escape and was hung in front of the laughing Frollo and weeping Quasimodo. In his despair, Quasimodo pushed Frollo from the top of the bell tower to his death.

A few days later, the unhappy Quasimodo found Esmeralda’s corpse in a mass grave, and lying down beside her, his arms around her corpse, stayed there until he died of starvation. Months later, their skeletons were found in an embrace, and as the undertakers tried to separate the pair, Quasimodo’s bones turned to dust.

Well, that was a really melodramatic story of love and revenge, wasn’t it? It’s a superb historical romance, but also a detailed history of medieval Paris and the cathedral as a silent witness to life. It’s a soap opera filled with archetypal characters and their epic myths. It’s also simply about Hugo’s defense of Gothic architecture and how, unless one cares for something intrinsically beautiful, it will decay and turn to dust like Quasimodo’s bones.

Until recently, most scholars believed that Hugo must have simply had a brilliant imagination to invent his character, Quasimodo. Even though the beast aspect of his character may have been based on earlier stories such as the “Beauty and the Beast” or the ancient Greek myth of Eros and Psyche, Quasimodo stands out as a real human being, a hunchback with a heart. And maybe, that’s exactly what he was, not so much a fictional character but a real man?

What came to light some years ago in a house in Cornwall, England, were the memoirs of a certain Henry Sibson, an English stonemason who was employed in the 1820s to work on repairs to the cathedral. Sibson had met a sculptor in Paris called Trajan who helped Sibson get a job at the cathedral by impressing upon the chief sculptor that Sibson was a talented English stonemason. Sibson recalls the chief sculptor was rather withdrawn and very quiet. He didn’t mix with the other workers, even though he was their supervisor. He was referred to as Monsieur Le Bossu by the others. Le Bossu is a French nickname for a hunchback, and Sibson confirms in his memoirs he had a humped back!

The researchers also found listed in the “Paris Almanac” for 1833, a sculptor named Trajan, who lived in the area on the left bank known as Saint-Germain-des-Prés, where Hugo lived at the time. Just to add another clue to Hugo’s knowledge of the hunch-backed stonemason, in an early draft of the Les Misérables he created a character called Jean Trejean, whose name he later changed to Jean Valjean. Coincidence, or did Hugo actually know not only Trajan, but maybe Monsieur Le Bossu personally? After all, his detailed descriptions of the cathedral throughout the book were very accurate, so it’s just as likely he probably met the very man who was to inspire his pitiful character.

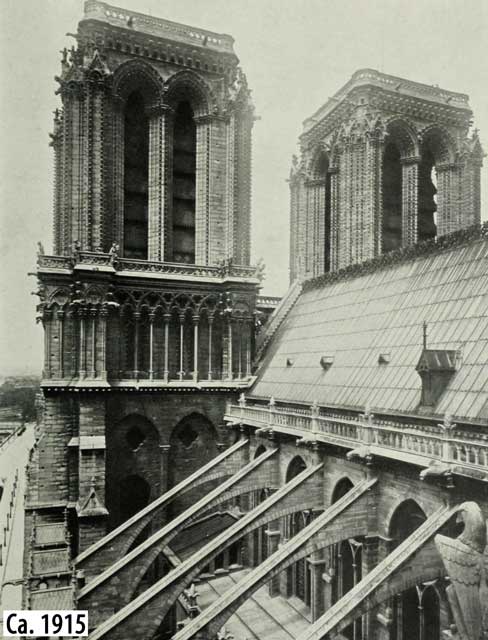

Very soon after it was published in 1831 The Hunchback of Notre Dame became a best-selling success around Europe and tourists flocked to Paris to visit Notre-Dame. So in 1845, the authorities, ashamed at the state of the building, ordered restoration work to begin on Notre-Dame’s exterior.

With the addition of idealized medieval gargoyles, decoration, and statues, all designed by architect, Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, Notre-Dame soon became the star of the Gothic show.

If you look directly up toward the cathedral rooftop and towers, you can see many gargoyles adorning the walls of the cathedral.

Gargoyles are waterspouts usually in the form of grotesque carved figures, the word deriving from the old French word, gargole, meaning throat. These are common on many large buildings and are simply decorative rainwater drains.

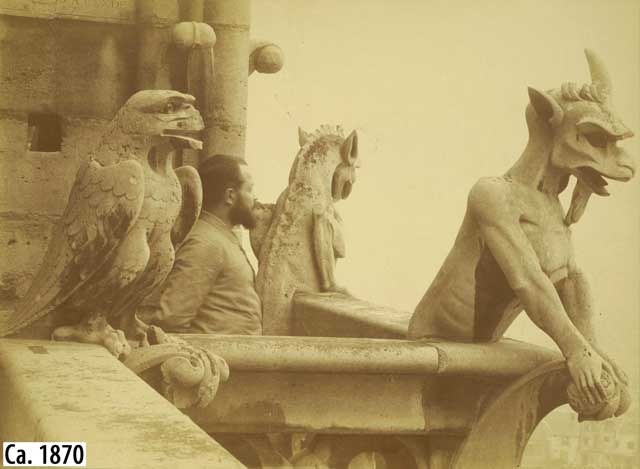

Fascinating as the gargoyles are, it is the Viollet-le-Duc’s chimera, the fantastic statues of hybrid beasts that live up there between the two towers, on galerie de chimère, or the Chimera Gallery, who steal the show.

Viollet-le-Duc, like Hugo, believed in bringing to life the medieval age. Both men, in their own ways, created a whole new approach to the old Paris that many had forgotten after the dramatic changes of the Revolution of 1789-1799.

Let’s now start the climb and follow in the footsteps of the real-life hunch-backed sculptor and his fictional double, Quasimodo.

Up here, is the Chimera Gallery, 46 meters (151 feet) above the ground.

You can gaze in awe and wonder across the whole of Paris and the square below, like your silent companions – chimeras.

Chimera was originally a mythical beast in Greek mythology, part lion, part goat, part snake. Since then, it has become associated with many fantasy monstrosities, so the word is now used to describe any hybrid of beasts, animals, or humans.

Viollet-le-Duc wanted to capture the soul of medieval, High Gothic architecture and the effect he achieved through his chimeras is perfect.

It seems as if this is their home and that they’ve always been here.

They represent all aspects of human nature; they grin, laugh, jeer.

There’s even a strange devilish dog eating a rabbit.

Some of the statues resemble hybrid men and animals, others elephants or hawks.

There are winged devils and thoughtful dwarves.

They all seem to be alive and have souls.

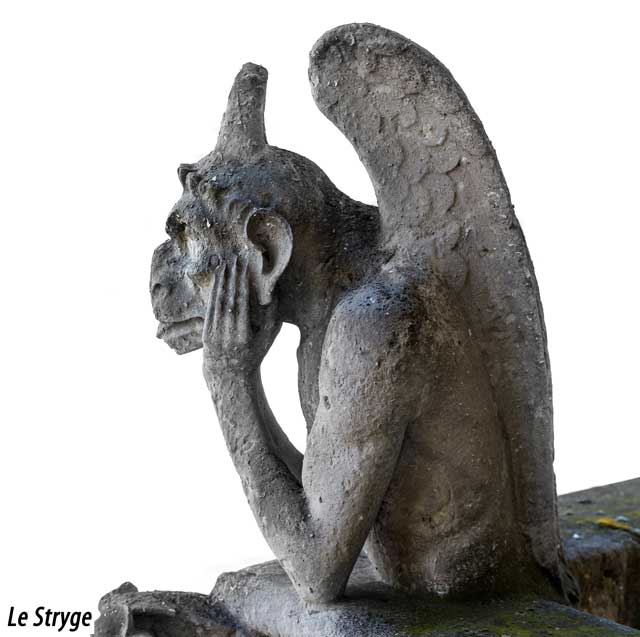

Many gaze thoughtfully into the distance like the well-known Le Stryge.

Le Stryge is the perfect example of Viollet-le-Duc’s passion for the grotesque and the Gothic, and it is the most famous of all the chimeras here.

Often called a vampire, Le Stryge (also Strix or Stryga), in fact, is not a vampire at all. Strix is the ancient Greek word for owl. In Latin, the family of owls is known as stirge, and you can see that this statue has wings, horns (certain types of owl have ear-tufts which resemble horns and are thus called horned owls), human arms, large ears, huge staring eyes, and a sticking out tongue.

In ancient Greece, screeching winged female demons, half owl, half woman, were all around the literature of their mythology. Strix were feared for their horrible habit of snatching newborn babies with their talons and sucking out their innards, or tearing them apart to eat their flesh.

The Roman poet Ovid recounted how strix attacked and tried to snatch King Procas in his cradle, but they were diverted with pig’s meat. Similar to the Harpies, half female, half winged creatures who plummeted down from the sky to grab human prey, strix are not vampires as such, but they did feed on flesh. In Romanian and Italian folk tales from the Middle Ages, they became associated with witches, and later with the vampire cult of 19th century Romanticism.

But does our almost friendly, bored, cheeky, contemplating Le Styrge look anything like a woman or a vampire? Not much. But there is something resembling an owl about it. After all, you are only seeing it in the daytime when most owls sleep. Perhaps when night falls, the bored thinker becomes a predatory night owl!

Let’s now move on and up the next spiral staircase to the bell tower.

From the top of the southern tower you have the most amazing 360-degree view across Paris.

You can see the Eiffel Tower to the west.

The Louvre and the Arc de Triomphe are to the northwest.

On top of the Montmartre hill, in the north, is Sacré-Coeur.

Below the spire you can see copper statues of saints.

One of the statues is actually of Viollet-le-Duc himself.

He is the only statue gazing skyward, a fitting memorial to his work.

Let’s carry on into the belfry itself and climb up the rather steep wooden stairs to get a really close view of the 17th century bell known as Emmanuel, which rings out the booming note of E-flat.

Weighing over 13 tons, legend tells that the bronze and copper bell was also made from gold and silver. This was from jewelry thrown into the huge burning cauldron of molten metal by local women to bring them luck or blessing from God.

Baptized Emmanuel by its godfather Louis XIV in 1681, it is the only bell remaining of the original 15 in the two towers in the 18th century. The others were destroyed and melted down during the Revolution.

The bell is rung on Catholic feast days of the year, like Christmas, Easter, Whitsunday, or All Saint’s Day, and on exceptional moments in history. One very special occasion was on August 24, 1944, when French and Allied troops arrived on the Île de la Cité, and the bell rang out to announced the liberation of Paris. In 2005, the bell rang 84 times to mark the death of Pope John Paul II, who was aged 84.

The bells in the northern tower were replaced with new ones for the 850 year anniversary of the cathedral in 2013.

Emmanuel was spared such a fate because of its historical value. The project created controversy in France. Historians and conservationists wanted to see the bells remain, but bell experts agreed that as they were merely 19th century replacements, the new ones were more in keeping with the originals in sound and clarity.

Going back down, let us tell you the brief legend of a ghostly bell-ringer. Yes, watch out, he may be about!

This ghost is not Quasimodo, but an 18th century bat lover. One night, a certain Dr. Grenier was on a bat watch in the belfry. Researching into how bats could see in the dark (long before the discovery of echo-location), he was allowed to stay up here alone with only a candle and a flask of wine. While sitting at the top of the creaky wooden ladder, he drank his wine, fell asleep, and crashed to the floor below and broke his neck.

Ever since then, it’s said that the ghost of Dr. Grenier haunts the belfry, and if you come up here alone at night, you’re certain to meet him and his friendly bats. Some say he turned into a vampire, only to boost the myth of bats and their association with blood-sucking demons.

Bats in the belfry or not, you have seen Paris, from the eyes not only of Viollet-le-Duc’s chimera, but also Hugo’s Quasimodo, and the ghostly doctor and his batty friends. It’s a long walk down, but you’ll never forget the experience.

Walking around, to the southeastern side, gives another perspective on the magnificent architecture of Notre-Dame.

Behind the cathedral stood for centuries the archbishop’s palace, that was demolished after the 1831 riots, like the treasury and sacristy building, but the palace was not rebuilt.

As you look up to the wondrous spire, standing 93 meters (305 feet) high, made of some 500 tons of wood and 250 tons of lead, you can understand why Viollet-le-Duc included himself among the copper statues of apostles, being the only one that faces upward.

It wasn’t so much arrogance but pride at what he had achieved.

It was Eugène Viollet-le-Duc who was more responsible than anyone else for the revival of the Gothic splendor of Notre-Dame in his restoration of the cathedral, that begun in 1844 and lasted 23 years.

Viollet-le-Duc was brought up in a well-to-do Parisian family, where at his mother’s afternoon salons for the intellectually elite, he met influential figures such as the writer Stendhal.

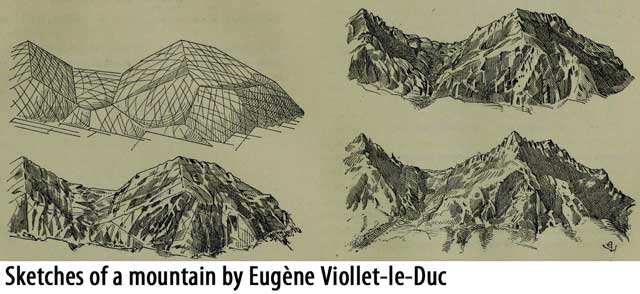

He drew thousands and thousands of sketches. These were mostly of nature. In his 20s, he climbed Mount Etna to see the live volcano during a long trip to Italy. He sketched rocks, landscapes, nature, plants, and flowers. His obsession with nature was revealed in his many books, which included lengthy chapters on cell structures, geometry, plants, and botanical growth. He believed there was more intelligence in a flower than in an artist or writer, and that crystal and rock were imbued with the divine.

Self-willed and innovative in his methods, Viollet-le-Duc wrote many papers and books. He wrote about geology, form, and architecture in a radical way. Far from the classical, stylized, and traditional schools of architecture, he wanted to reveal that the ideal form of growth and life wasn’t rooted in classical Greece or Rome but came from ancient history, from those societies who lived close to the Earth. From those peoples who were essentially animist, in other words, who found the divine in all of nature. These ancient pagan tribes of Europe were the Celts and later the Goths. It was this simple, humble, yet magical form of the “real” Gothic that inspired him.

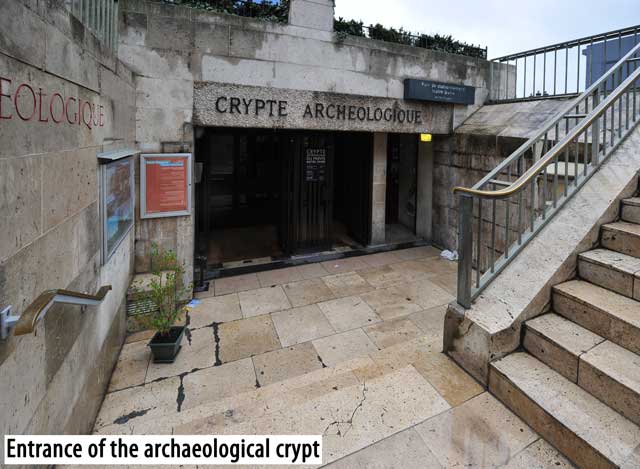

On the northwestern side of the Place du Parvis Notre-Dame is the entrance to an archaeological crypt, hardly noticeable by passing tourists.

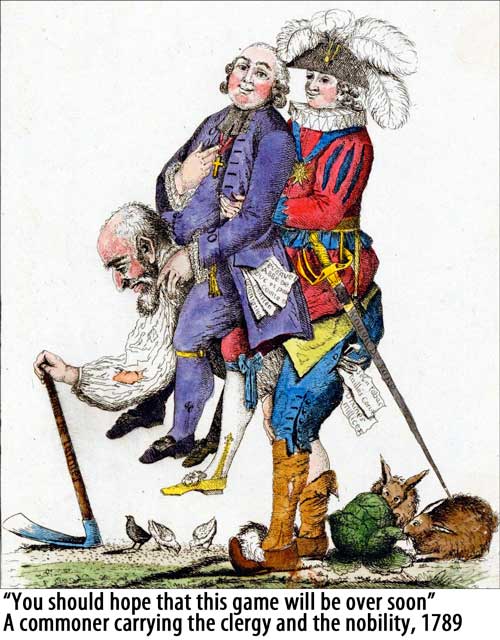

The exposition in the archaeological crypt shows how Paris was very different from the current view. The crypt also holds a secret about the terrible conditions of 17th and 18th century France before the Revolution, which isn’t apparent from the glamorous image up on the surface.

As you walk down the steps and into the museum, remember that although the display is modern, the remains are ancient, and it’s extraordinary to think that most people walking on the square don’t realize what is below them.

As you enter, you see exhibits telling about the early history of Paris.

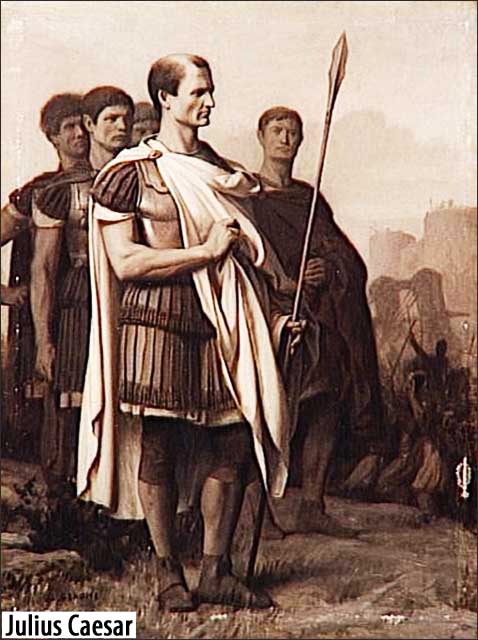

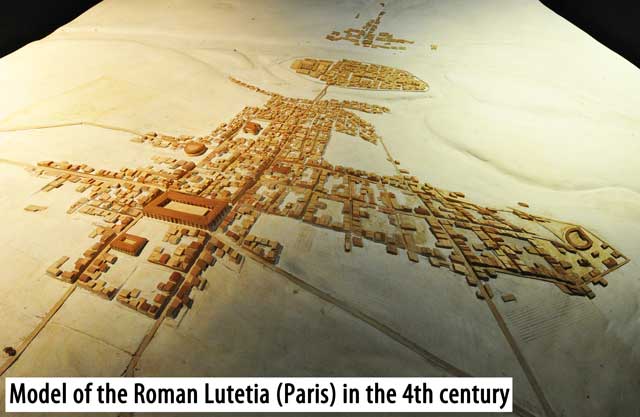

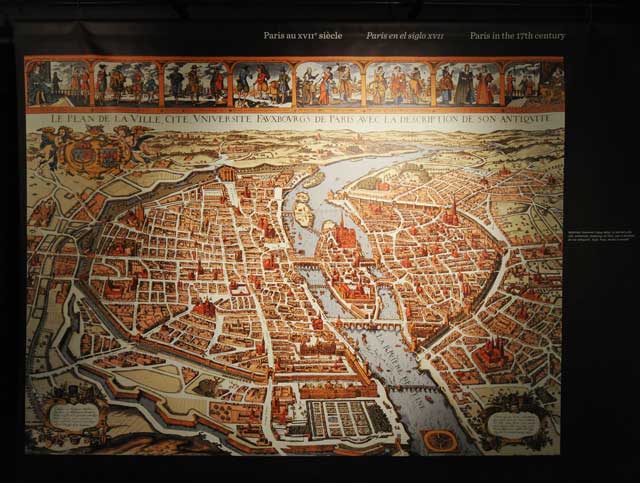

Where Paris is now, a port settlement, called Lutèce by the Parisii tribes, had been a trading post of great importance since the 4th century B.C.E.

When Julius Caesar invaded Gaul in 58 B.C.E., the Romans named it Lutetia. This was a strategic base for the Roman Empire to the south and the Celtic lands it wished to conquer to the north. Gaul was the name of the area that made up most of France as it was then, while Aquitaine and Provence, now also part of France, were separate kingdoms.

The name Lutèce or Lutetia has many possible origins. Some believe the word is simply derived from the Roman word for mud, lutum. But the original inhabitants, the Parisii tribes, who came from the swampy valleys of the Essone River further north, used a similar word in Celtic for swamp, luto. Whatever the case, the Romans decided to call it Lutetia.

The town was renamed Paris, referring to the Parisii tribes, under the ruling of Emperor Julian in the 4th century.

In the showcases you can see a model of the Roman city, including the main Roman settlement and forum on the left bank.

There is also a model which gives a good idea of how Paris looked in the 14th century.

In the center of the gallery there is a display of different archaeological remains.

These remains were discovered and archaeological excavations conducted in 1965-1972 during the construction of an underground car park in front of Notre-Dame Cathedral.

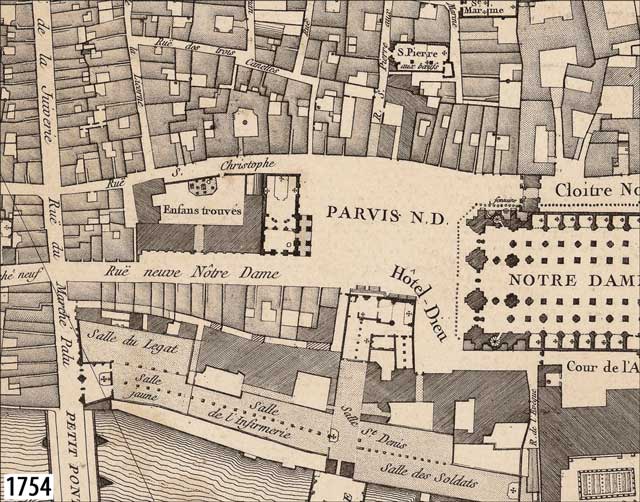

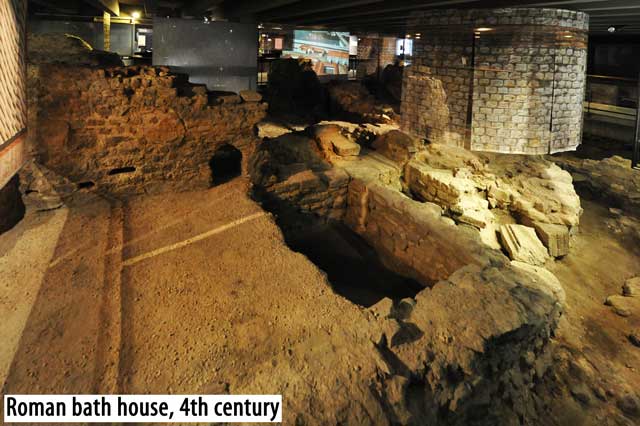

What the diggers found were layers of centuries of history, including a Roman bath house; sections of a street called Rue Neuve Notre-Dame, dating from the Middle Ages, which led right up to the front of the cathedral; the original site of the Hôtel-Dieu Hospital; and the ruins of the Hospice des Enfants-Trouvés, the orphans hospital.

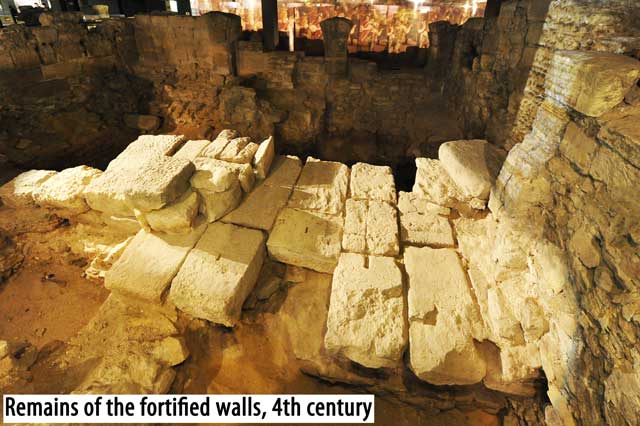

First, you can see parts of the oldest ramparts or fortified walls, which surrounded the Île de la Cité island, built of solid stone blocks, mined from the limestone, which is under the whole of the city of Paris. These blocks were found among the ruins of other Roman monuments, abandoned after the invading Franks conquered Paris in the 6th century.

As you continue along the gallery, and down the steps, you see the remains of the ancient dockside of the port of Lutetia. The stone walls were both as a protection against the floodwaters and also as anchorage points for the loading and unloading of cargo.

There had been an important trading post of the Parisii tribes at this location in the 4th century B.C.E. In those days the Île de la Cité was at least seven meters (23 feet) below the present level. These were mosquito-infested, swampy areas, often submerged by flooding, with waters difficult to navigate with the rise and fall of the tide. But the Seine River, from an original word meaning winding, was navigable from here all the way down to the sea and was thus a major trading river. Under Roman rule, Lutetia became a thriving commercial port.

Back in the main gallery, you are now standing beneath the center of the square on the old Rue Neuve Notre-Dame which used to be the street that led up to the front entrance of Notre-Dame Cathedral. Until 1745, there were many tiny shops, including booksellers, goldsmiths, engravers, scribes, and apothecaries.

Next, you see the remains of the Hospice des Enfants-Trouvés foundling hospital, built in 1750 by the acclaimed French architect Boffrand.

In the beginning of the 17th, century Hôpital Hôtel-Dieu, now located at the other side of the square, was then a house which cared for pilgrims, lepers, and enfants-trouvés, meaning foundlings. Rather than being found, these were actually infants who had been abandoned. The word hôpital, or hospital, had a general meaning too in those days. It was more like a hospitality home, run by local religious charitable institutions for the poor or sick. But as Paris expanded its population, so too was there a rise in abandoned infants.

In the first half of the 17th century, a few charitable wealthy widows opened the first maison à la couche, or maternity house, where pregnant girls could go to give birth and then abandon their infants. It soon became apparent that the employed nurses were not so compassionate as they appeared. The infants were usually sold off either to become farm laborers or to the mendicants – the beggars who lived by charity in the name of their religious faith. These men, and sometimes women, would sit on street corners in the rain and wind, holding a screaming baby above their head to incite pity and receive money. The infants usually died of starvation or the cold, and the mendicants had little sympathy for them. Other babies were sold for occult rituals or to medical students for experiments on human bodies.

The scandalous first maison à la couche didn’t last long, and in 1638 a pious Catholic priest called Vincent de Paul created the first foundling house in a wing of the old Hôtel-Dieu Hospital.

He installed tour d’abandon, or the baby hatch, in the wall of the building. And with an order of nuns that later became known as Seours de Saint Vincent de Paul, Vincent’s foundling facility became a safer way to abandon an infant. Baby hatches were places where one could leave a baby anonymously and were still in use in France right up until the end of the 19th century.

Thousands of babies were abandoned every year on steps of churches and cathedrals, including Notre-Dame. In the 14th century, a cradle was put on the floor of the cathedral. On various festivals and saint days, an infant would be displayed in the cradle, to toy with the conscience of the people.

Three centuries later, while entertainers juggled, played, or danced in the Place du Parvis, many babies screamed for food and love behind the closed doors of the Hôtel-Dieu Hospital, but it was the best that Vincent could do. From 1638, Louis XIII gave 4,000 livres annually, equivalent to some $40,000 of today, to la couche de Parvis as the hospital was commonly known. This was increased to 12,000 livres annually in 1644 by Queen Anne of Austria, the mother of Louis XIV who served as his regent after her husband’s death.

By the middle of the 18th century, with an alarmingly growing number of abandoned infants, the Catholic administrators decided to demolish the churches St. Christophe and St. Geneviève des Ardents and build a separate foundling hospital, the Hospice des Enfants-Trouvés, on the square. But the new hospital was not without its problems, and many babies died from overcrowded beds, lack of ventilation, contagious diseases, and polluted water.

When the infant arrived at the hospital, if they showed no sign of disease, they would be given to a wet-nurse. Eventually, they would then be sent to the countryside to families who were paid a few sous per week to nurse and feed the infants. On paper this sounded hopeful, promising, and a way to save lives. But unfortunately, a new profession developed. The hospital had little choice but to employ meneurs. These were kind of agents or ringleaders, who saw to the organization of the wet-nurses, recorded the deaths of infants, found new wet-nurses, took care of the transport of the babies and the payments. Many women who lived in the provinces, also began to use the meneurs to arrange to take their babies to the foundling hospital in Paris. Whether they arrived dead or alive, it was the same price, and the meneurs and their growing baby dealing business flourished.

It was one of the most scandalous and saddest professions to have grown out of a charity. Between 1783-88, around 10,000 babies were transported to and from the countryside in terrible conditions. They would be piled up in carts one on top of the other. They were covered with filthy, thin covers, and because they were packed like sardines, their accompanying wet-nurses would have to walk behind in the rain, cold, snow, or heat. The infants could hardly manage to suckle, and the wet-nurses, because of their lack of food and bad health and physical exhaustion, could only provide unhealthy milk or even gave the infants wine if their milk was non-existent.

The wet-nurse agents soon became dealers in babies too. One story recounts of one meneur, called Mercier, who regularly carried newborns from the freezing cold northeast region of Lorraine to be deposited at the foundling hospital in Paris. He usually carried three in a box on his back. He walked for days without feeding the infants, and if he did, he used an old sponge soaked in cow’s milk. If one died, which was usual by the time he reached Vitry, the halfway mark, he’d leave it by the roadside, then carry on to Paris. His only concern was to be paid, deliver his load, and return for more.

In the 1780s, in Vendeuil, not far from Paris, a small provincial town where foundlings were often sent, the hospital’s chief meneur, Jean Grenier, reported that in one year eight infants passed through the hands of a wet-nurse called Marie Anne Blondeau. Seven of which died within a couple of weeks. With her own children to feed and wean, Blondeau would probably have favored her own infants, and in her destitute state, lack of hygiene, and bad health, her milk would hardly have been sufficient to sustain babies already near death’s door after their terrible journey from Paris.

Many of these infants usually died from the effects of diarrhea and malnutrition. In statistics from information recorded, the babies had a one in ten chance of surviving until the age of ten, and 60 percent didn’t even reach their first birthday. Records reveal that between 1640 and 1789, the hospital received around 390,000 abandoned babies from all walks of society. During the Revolution of 1789-1799 the hospital was closed and transferred to a building in Rue d’Enfer on the left bank of the Seine River.

During the 1870s “war” against old Paris most of the old churches and buildings on Île de la Cité were demolished, including the Hospice des Enfants-Trouvés, which ironically, had long been abandoned, just like its infants.

The early history of Paris continues to be displayed along the walls.

Looking at the early maps of Paris you can see how the city expanded.

By the end of the 3rd century, at the height of Roman rule, the whole area of the Île de la Cité was built up with extravagant temples and villas for the wealthy Roman merchants with their own thermal baths. And among the excavated ruins in the middle of the gallery you can see the remains of the 3rd century Roman house.

There are also remains of a Roman bath house from the 4th century. The Romans were very fond of bathing. They didn’t have just one bath house, but usually three built together. One could wander from one bath to the next through various pillared terraces and perfumed courtyards, and then on to the meeting room to catch up on the latest gossip or scandal.

The first bath was filled with warm water to warm you up. The second was as hot as a sauna, where your slave would cover you in oil and scrape off your dirt with a curved knife called a strigil. The last bath was for cooling off, called frigidarium, and obviously as cold as a fridge.

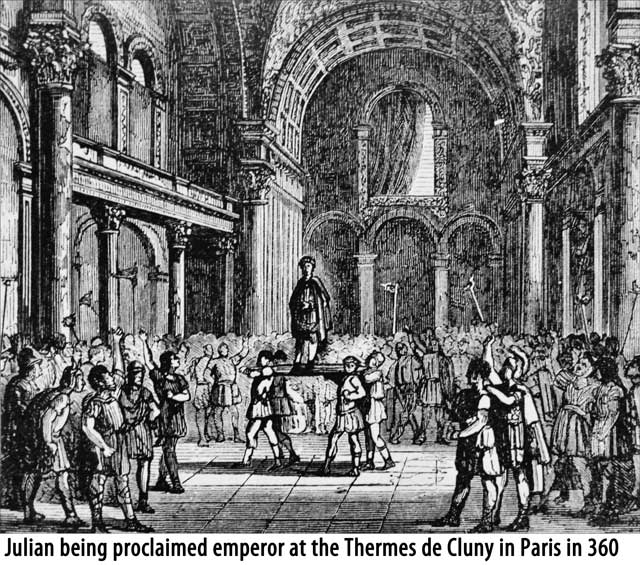

One Roman who loved his baths was Emperor Julian. In the 4th century, Roman life was particularly dangerous if you happened to be associated with the dynastic rulers. Whole families were massacred or poisoned in the rivalry for the ability to rule. Julian was only six when the corrupt sons of Constantine massacred his family.

With the success of Roman rule in Gaul, the Frankish tribes had begun to counterattack the new Roman settlements in northern Europe, so Julian was ordered by his emperor cousin, Constantinus, to command the Gaul legions and sort out the warring tribes.

Julian willingly left for Paris and lived there with his consort, Helena. His efficient restoration of peace and order in the north created envy among the high-ranking generals and officials back in Rome.