Welcome to the WanderStories™ tour of the top 10 sights in London. We are now ready to take you on your personal tour of these world famous landmarks.

We will also tell you the brief history of London and several additional stories about British cuisine, traditions and customs, holidays and festivals, humor and jokes.

We, at WanderStories™, are storytellers. We don’t tell you where to eat or sleep, we don’t intend to replace a typical travel reference guide. Our mission is to be the best local guide that you would wish to have by your side when visiting the sights. So, we meet you at the sight and take you on a tour.

WanderStories™ travel guides are unique because our storytelling style puts you alongside the best local guide who tells you fascinating stories and unusual facts recreating the passion and sacrifice that forged the beauty of these places right here in front of you, while a wealth of high quality photos, historic pictures, and illustrations brings your tour vividly to life.

Our promise:

• when you visit these top 10 sights in London with this travel guide you will have the best local guide at your fingertips

• when you read this travel guide in the comfort of your armchair you will feel as if you are actually visiting these top 10 sights in London with the best local guide

Welcome to London. There is only one thing to do now – visit!

Let’s go!

Your guide, WanderStories

Once you have read this book please review it, we truly appreciate your feedback.

Please subscribe to the FREE WanderStories™ travel e-magazine, Armchair Travel Guide at: wanderstories.com/travel-magazine

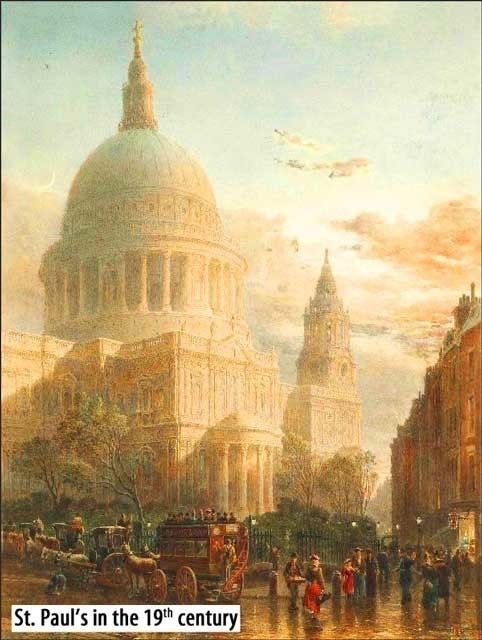

St. Paul’s Cathedral

Address: St. Paul’s Churchyard

51°30'49.0"N 0°05'53.0"W

The current building of St. Paul’s is the fifth religious building on this site. The ground is well suited for the construction of a cathedral as it rests on a low hill and in times past would aid the cathedral’s purpose in acting as a focal point for the nearby population for Christian worship.

In the area in front of the west entrance of St. Paul’s Cathedral is a statue of Queen Anne.

The first Queen Anne statue on this spot was erected in 1712. The statue that you see here now was erected in 1885.

This statue also marks the spot where the only public execution that happened on the grounds of St. Paul’s occurred.

It was here on May 3, 1606 that Father Garnet, a Roman Catholic priest who had been accused of being one of the main conspirators in the Gunpowder Plot, a plan to assassinate King James I by blowing up the House of Lords, was executed.

This statue of Queen Anne has been the target of protesters since its erection. One anonymous Catholic, still not happy with the dethroning of the Catholic monarch, James II in 1688, wrote on the statue: “with her face to the brandy-shop and her back to the church.”

Recently, in 2012, the statue became the target of a protest group called Anonymous that dressed Queen Anne in a mask and placed protest signs all around the statue.

Let’s go up the steps and enter the cathedral through the west portico.

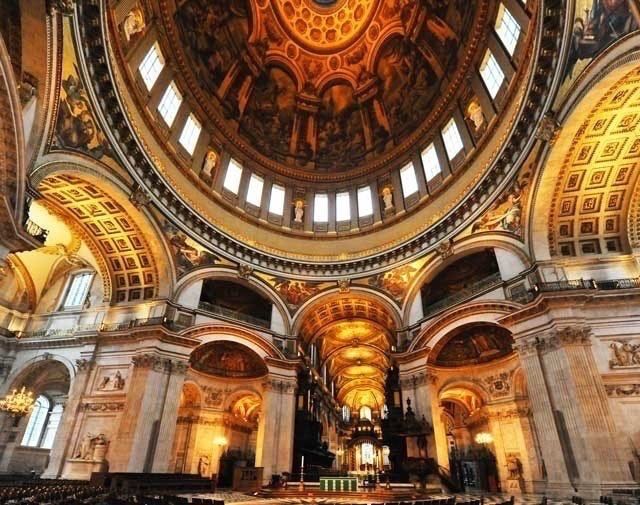

And right away you get an excellent view from the nave, which is the long central section of the cathedral that leads to the dome. This is a public and ceremonial space, designed for congregations at large services.

St. Paul’s is a functioning church, with daily services and frequent weddings and other ceremonies being held here. One of the most famous weddings to take place at St. Paul’s was the wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer in 1981.

Although there are many monuments within St. Paul’s, the majority of these commemorate military heroes. Westminster Abbey was traditionally seen as a place for heroes of the literature and the arts to be buried, so there are not many artists and writers commemorated in St. Paul’s.

Let’s take a look around, starting at the west side of the cathedral and the two small chapels that are there.

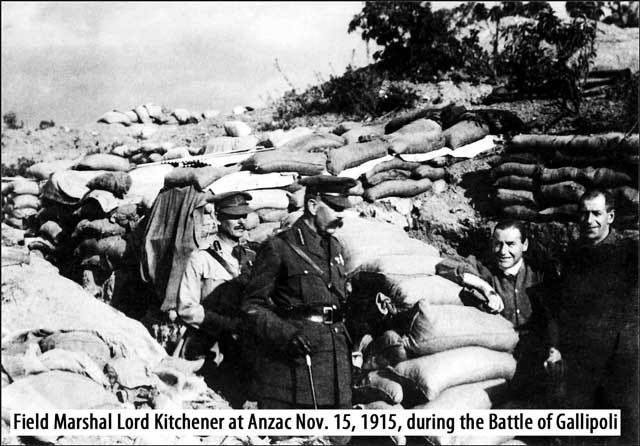

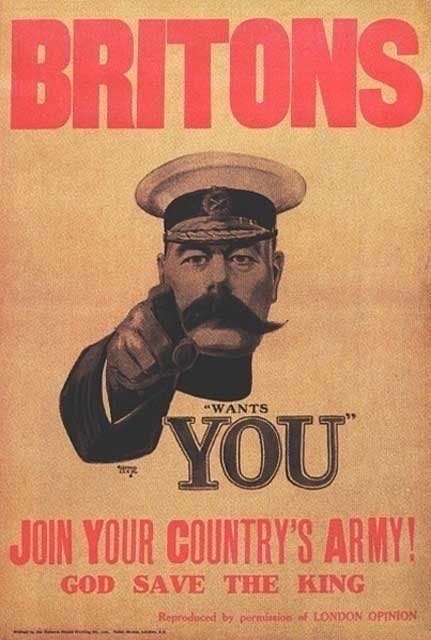

To the left of the entrance is the All Souls Chapel, which is currently dedicated to Lord Kitchener and the military servicemen who died in World War I.

Lord Kitchener was the Field Marshal who restructured the British Army during World War I.

His face is well-known in British culture, even today, due to a poster “Lord Kitchener Wants You” that was used in a massive recruitment campaign.

The next chapel on the same side is called St. Dunstan’s Chapel, and as its name suggests is dedicated to St. Dunstan, who became Archbishop of Canterbury in 959.

This dedication is relatively new, and before 1905, it was known simply as the Morning Chapel, as it was in constant use for daily morning and early Sunday services.

The chapel has some appealing features including two mosaics: one an adaptation of a fresco by the Italian painter Raphael, and the other is a memorial to Archdeacon Hale, a 19th century English churchman who operated in London.

Heading down the nave you can see, on both sides, the unusual semi-circular recesses, which break up the aisles on both sides.

It is said that they had been placed here with the intention to convert these recesses into lines of chapels for individual private worship and prayer.

These recesses are, for the most part, now used to house the tombs and shrines of the past military heroes of Great Britain.

Let’s discuss a few of the more prominent monuments in detail.

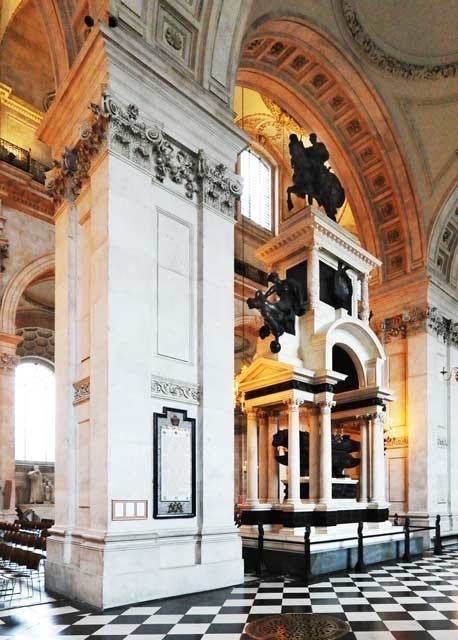

The first is the monument to Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington who was the British commander who defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

This monument was originally installed in one of the chapels, but was taken out so that the viewer could see the entire sculpture.

There are various allegorical figures on the side of the monument such as “Bravery trampling over Cowardice” and “Truth plucking the tongue from Falsehood.”

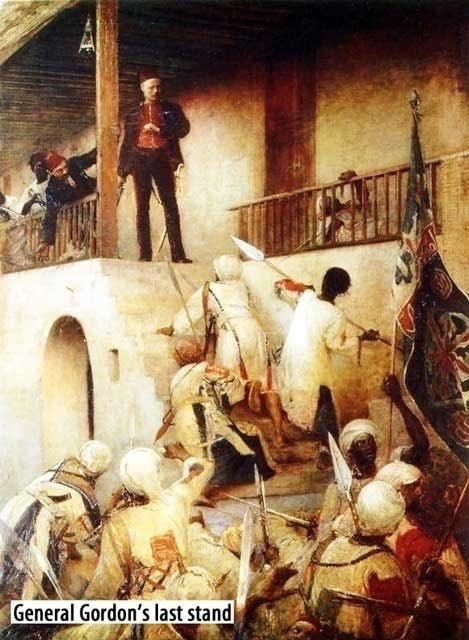

Another notable tomb on the cathedral ground floor is that of Major-General Charles George Gordon, a British army officer and administrator who died in combat in 1885.

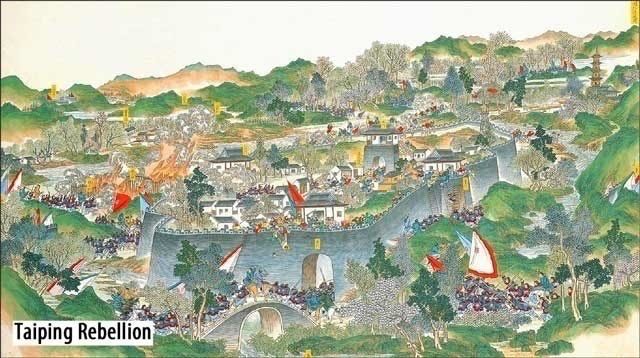

He was well-loved by the Victorian-era British who saw in him as the epitome of martial bravery. He was in action in the Crimean War 1853-56. Then he fought in China in the 1860s, where he was part of a group of European officers who led a force of Chinese soldiers that helped the Qing dynasty to put down the Taiping Rebellion, one of the deadliest civil wars in world history.

In 1884, Gordon was sent by the British Government to Khartoum, Sudan to evacuate British soldiers and civilians from the besieged city.

After evacuation, General Gordon defied orders and stayed behind with a small number of soldiers and organized a city-wide defense of Khartoum. The besieged force of Gordon’s lasted for a year, to the great admiration of the British public at home.

The British government at the time hadn’t wanted to get involved in the civil war occurring in Sudan and because of that didn’t send a relief force until public pressure became so strong that they had no choice.

Unfortunately, it was too late and by the time the relief force arrived, the city had been taken, and General Gordon had been beheaded by the Mahdi rebel forces.

His death caused widespread sorrow throughout the country and his tomb at St. Paul’s is often covered in flowers by those wishing to pay their respects to Gordon.

Li Hongzhang was a leading statesman of the late Chinese Qing Empire, and in 1896, he paid a visit to St. Paul’s Cathedral. Here, he decorated General Gordon’s tomb with magnificent wreaths to give thanks to Gordon’s efforts in protecting the interests of the Qing Empire in China in the 1860s.

Let’s go on to take a look at a brass inscription, which commemorates the loss of HMS Captain, which sunk in 1870 with Captain Cooper Coles aboard.

Captain Coles was the inventor of turret ships – the 19th century type of warships; the earliest to have their guns mounted in a revolving turret, instead of a board-side arrangement.

The inscription not only details the tragedy at sea, but also highlights the importance of the small problem that caused the tragedy; namely a design fault in the hull of the ship, less than half meter (1.6 feet) in length.

Let’s now proceed to the dome area.

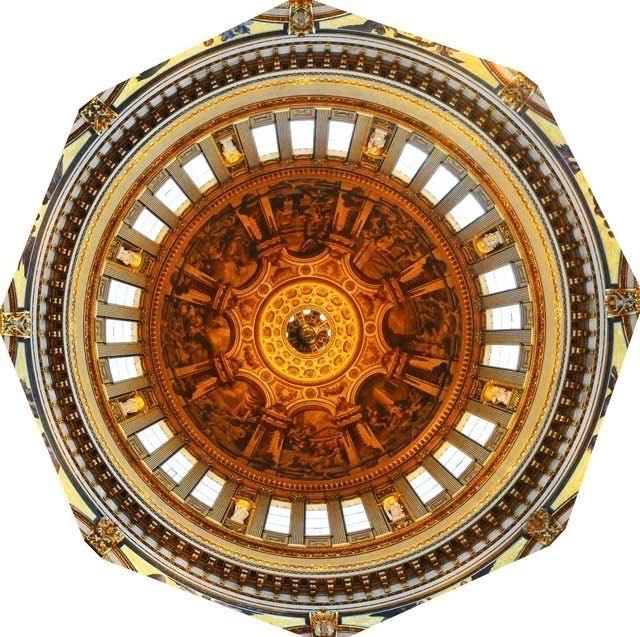

Looking up to the famous dome of St. Paul’s you can see the paintings by the English painter, James Thornhill, depicting the pivotal moments of St. Paul’s life.

The paintings were done in monochrome, much to the disgust of the cathedral’s architect, Christopher Wren, who wanted to use mosaic as a medium.

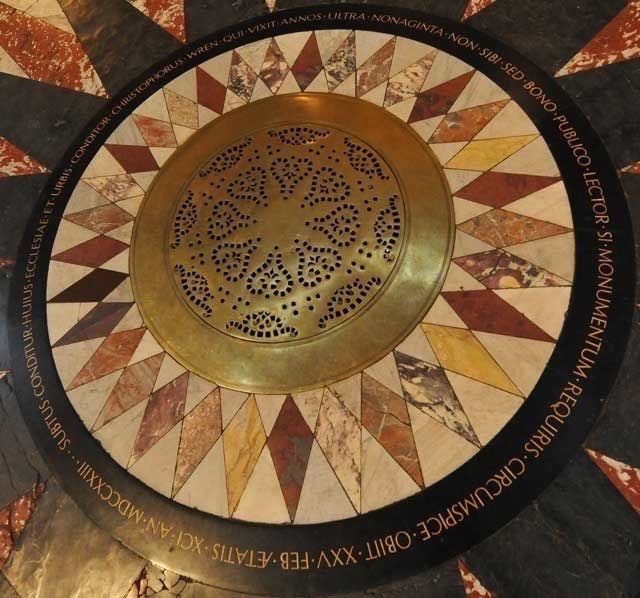

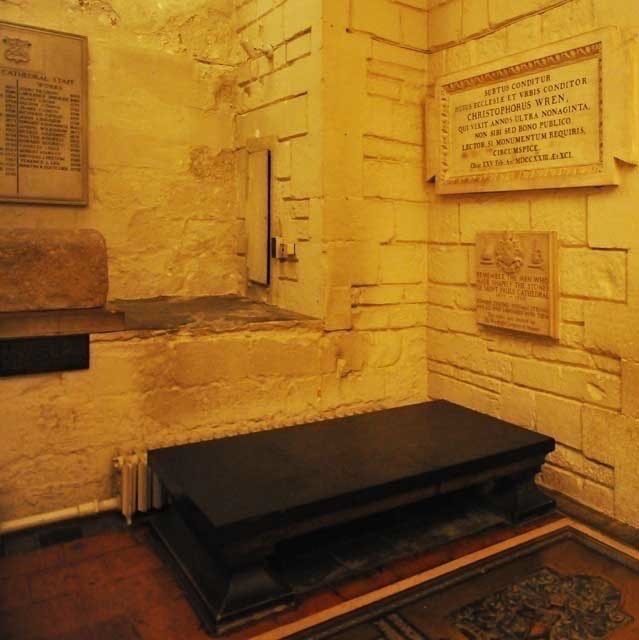

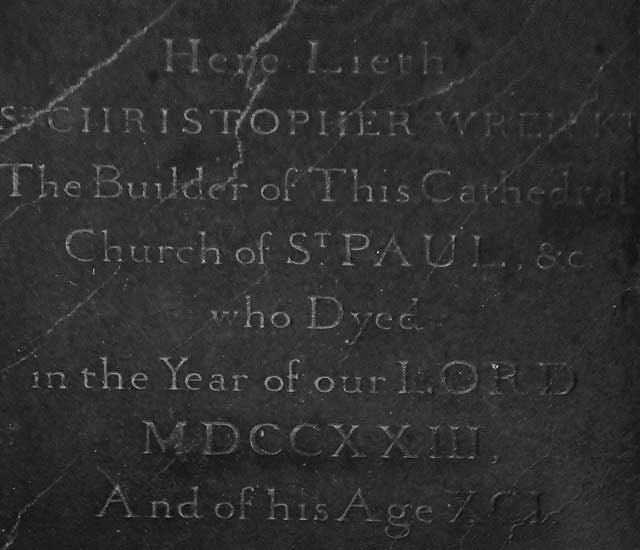

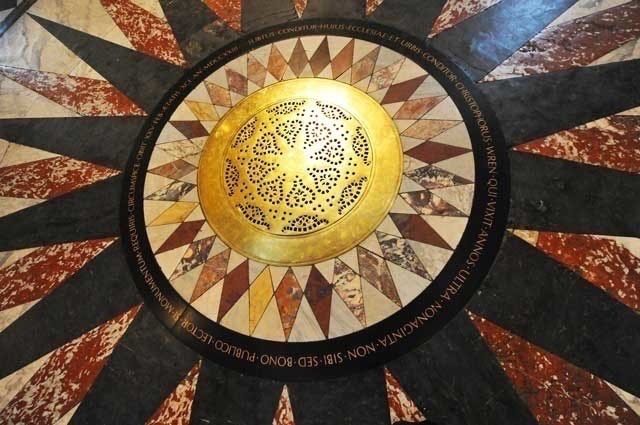

On the cathedral’s floor directly below the center of the dome is a Latin inscription on a circle of black marble, which reads: “SUBTUS CONDITUR HUIUS ECCLESIÆ ET VRBIS CONDITOR CHRISTOPHORUS WREN, QUI VIXIT ANNOS ULTRA NONAGINTA, NON SIBI SED BONO PUBLICO. LECTOR SI MONUMENTUM REQUIRIS CIRCUMSPICE OBIIT XXV FEB AETATIS XCI AN MDCCXXIII.”

It translates in English as, “Here in its foundations lies the architect of this church and city, Christopher Wren, who lived beyond ninety years, not for his own profit but for the public good. Reader, if you seek his monument – look around you. Died 25 Feb. 1723, age 91.”

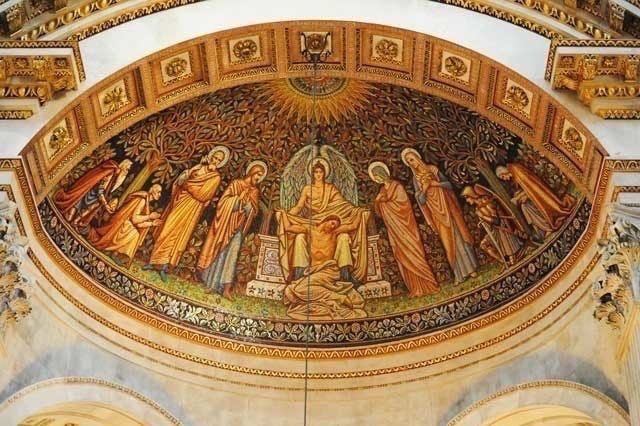

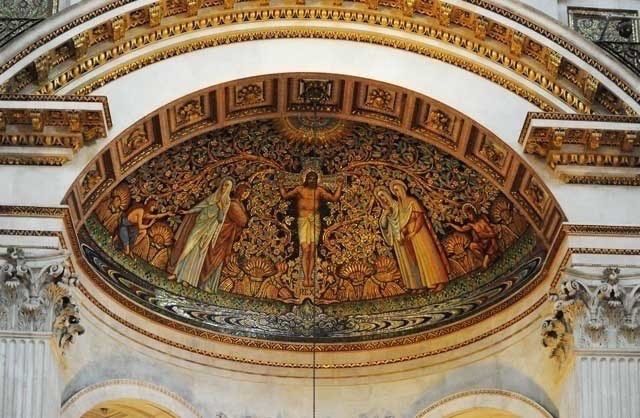

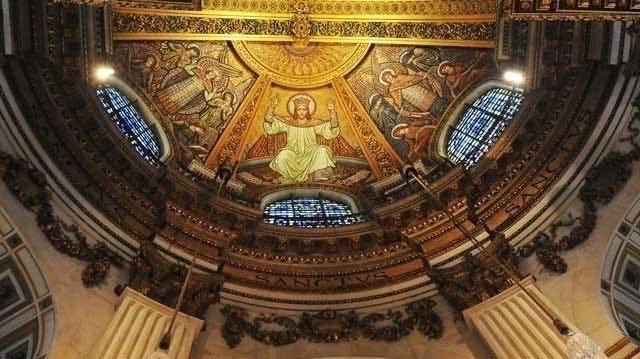

Surrounding the central dome of St. Paul’s are superimposed arches filled with mosaics from the end of 19th century.

The other mosaics in the concave quarter domes depict scenes from the Gospel of St. Paul.

One of the oldest and most interesting tombs on the cathedral ground floor is that of John Donne, in the South Quire Aisle, which is on the right hand side beyond the dome area.

He was an English poet and Dean of St. Paul’s from 1621 to 1631.

It is said that Donne had sat for a portrait in death clothes while he was alive, and the image of Donne in that painting was worked into the design of his tomb.

Looking at the tomb of Donne he appears in his grave-clothes gathered up into a sort of crown.

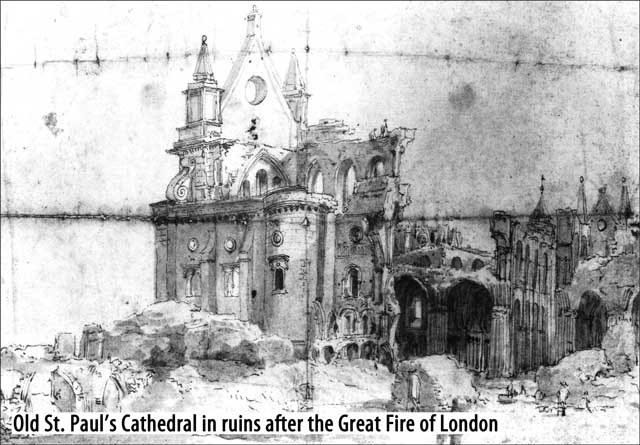

This tomb was one of the few tombs to survive the destruction of the old St. Paul’s in the Great Fire of London in 1666. On the white marble of Donne’s tomb, you can still see the scorch marks from the effects of the fire.

There are a few remains of the old St. Paul’s tombs gathered in the crypt; however, Donne’s tomb here is by far the best preserved.

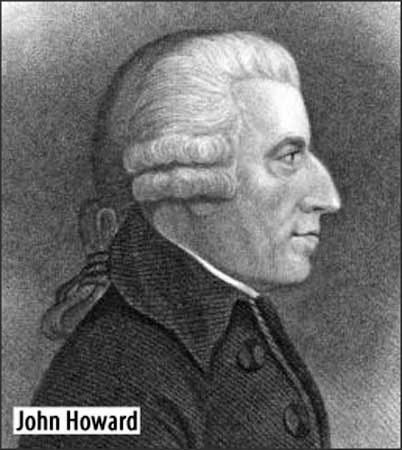

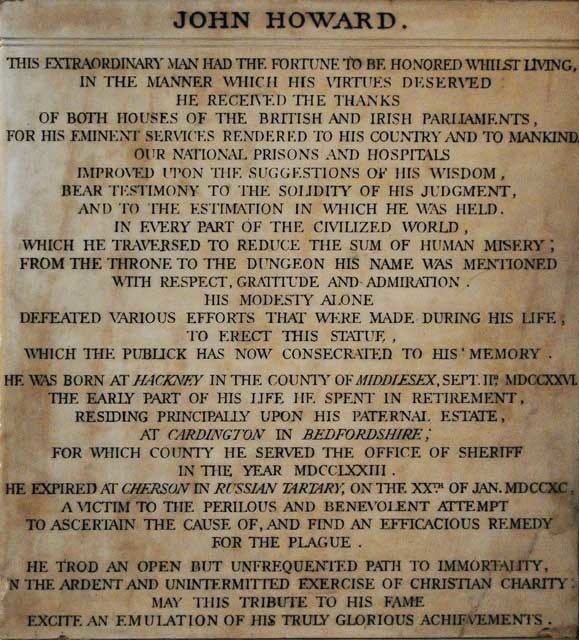

One of the first commemorative statues created and installed in St. Paul’s was in 1790 and of John Howard, the English philanthropist and prison reformer.

John Howard was born into a prosperous middle class family and lived a comfortable life as a country gentleman.

His life changed dramatically when he was appointed the High Sheriff of Bedfordshire. As part of his duties he decided to inspect the county prison, and he was shocked by the conditions in which the prisoners existed. Many people jailed in the county prison were debtors, most of them once respectable local merchants who were placed in the same communal cells alongside common thieves.

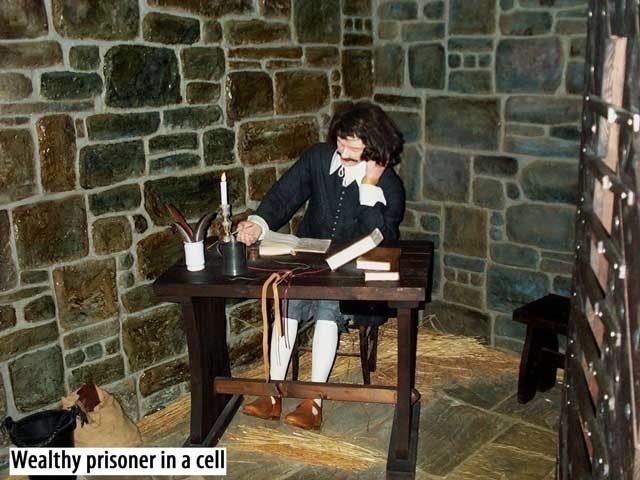

The debtors would not be allowed release until they paid off their debts, which meant that many debtors would find themselves imprisoned indefinitely. Prisons were treated as private residences by the persons running them known as gaolers, which meant that many prisoners were forced to pay for their own imprisonment including bedding and food.

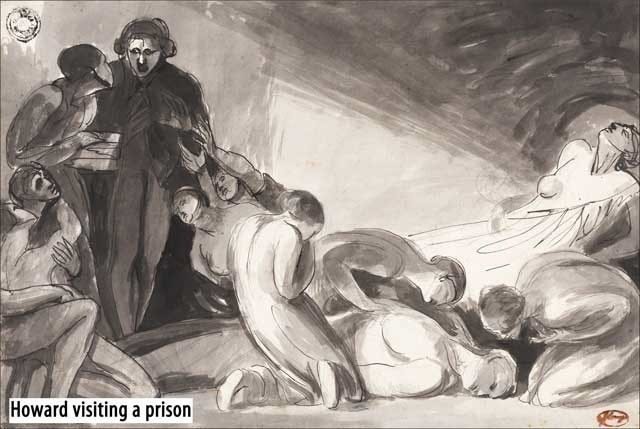

John Howard had hoped that he would be able to find an English prison that would act as a good example for the dreadful Bedford county prison. However, on his tour he found that the conditions of prisons throughout England were similar to that in Bedford.

In one instance John Howard wrote of Ely prison in 1755, “Ely Gaol was the property of the Bishop, and because of the insecurity of the old prison, the gaoler chained the victims down on their backs on the floor, across which he placed several iron bars, with an iron collar with spikes about their necks and a heavy iron bar over their legs.”

Many gaolers would often not let prisoners leave the prison without paying a substantial bribe, even if they were innocent. This meant that innocent people that happened to be poor were often left in prison without any opportunity to leave.

Not content with his investigations, he then decided to tour other prison facilities in Wales, Ireland, Scotland and across Europe; he even traveled to Eastern Europe and as far away as Russia. Over the course of his investigations John Howard traveled a distance of over 80,000 kilometers (50,000 miles) and spent £30,000 of his own money in his vast investigation; this was the equivalent of $5 million in today’s currency.

It was while on one of his prison visits to Kherson in modern day Ukraine that at the age of sixty-three he contracted typhus and died. He was buried in Stepanovka in Ukraine.

Of the many detailed proposals that Howard recommended in his influential book, “The State of Prisons in England and Wales” published in 1777, one was that prisoners should be kept in single cells rather than communal cells to encourage personal hygiene and health.

The inscription below his statue says:

“This extraordinary man had the fortune to be honored whilst living,

in the manner which his virtues deserved

he received the thanks

of both houses of the British and Irish Parliaments,

for his eminent services rendered to his country and to mankind.”

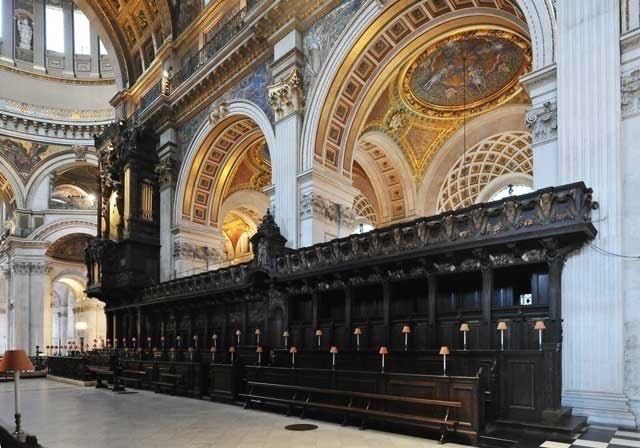

The Quire is the continuation of the nave beyond the dome area at the east of the cathedral. This is where the choir and the priests normally sit during services.

The Quire was the first part of the cathedral to be built and consecrated.

The Bishop’s throne, or cathedra, is on the south (right) side.

The organ was installed in 1695 and has been rebuilt several times. It is the third largest organ in the U.K., with 7,189 pipes, five keyboards and 138 organ stops. Its case was made by Grinling Gibbons, the famous wood carver whose work is seen in many royal palaces and great houses, and is one of the cathedral’s greatest artifacts.

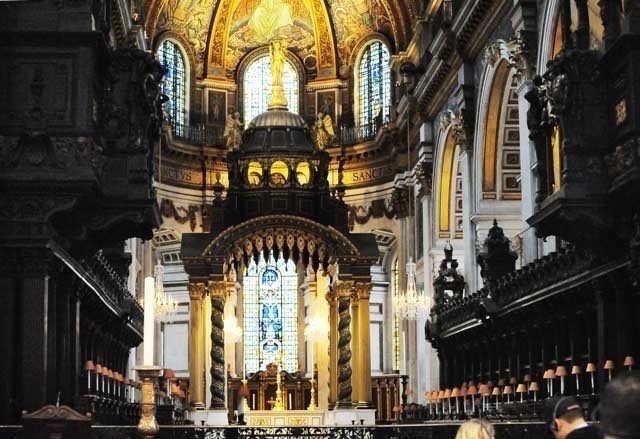

At the far end of the Quire you can see the high altar. Originally, the cathedral had a simple, large Victorian marble altar and screen, which were damaged by a bomb in World War II.

Let’s go closer to have a better look.

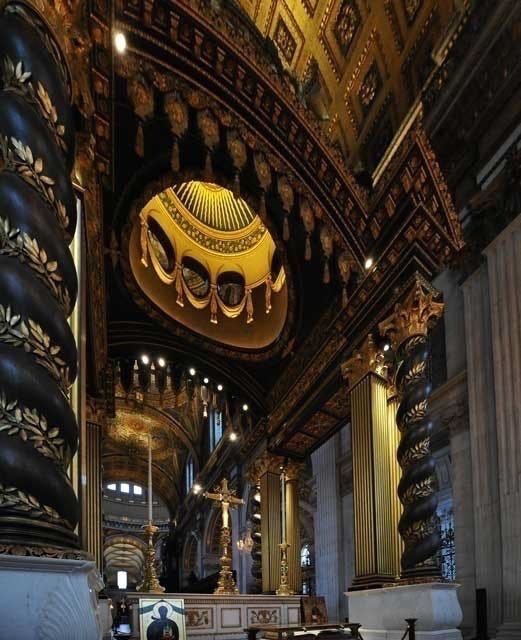

Go through magnificent gilded gates on the sides of the altar.

The present high altar dates from 1958 and is made of marble and carved gilded oak. It features a magnificent canopy based on a sketch by Wren.

Behind the high altar is the Jesus Chapel. It is also known as the American Memorial Chapel, dedicated in 1958, as it honors American servicemen and women who died in World War II.

Look up to see a wonderful mosaic.

In the latter half of World War II there were a great number of American military personnel stationed in the southern part of England; including in and around London.

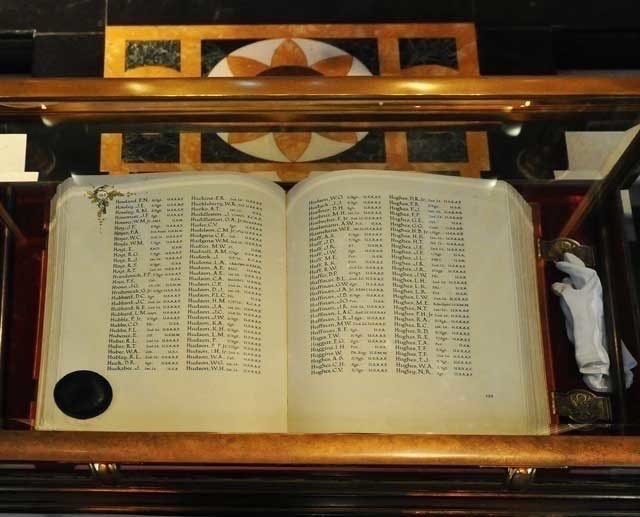

This part of St. Paul’s was destroyed during the bombing of London, so when it was being rebuilt it was decided that it would be dedicated to the more than twenty-eight thousand Americans who gave their lives while on their way to, or stationed in, the U.K. during World War II.

All of their names are recorded in a roll of honor that is on display in a glass-encased book next to the chapel’s altar, where a page is turned everyday so different names are displayed.

The stained glass window behind the Memorial Chapel was damaged in the bombing and was restored in the 1960s. It is the main window of the cathedral and is also dedicated to Americans serving during World War II. The wood paneling of the altar, carved in the style of Grinling Gibbons, contains birds, plants and flowers native to America. There is also a medallion with the head of General Dwight Eisenhower, the U.S. Commander-In-Chief of Allied Forces during the war.

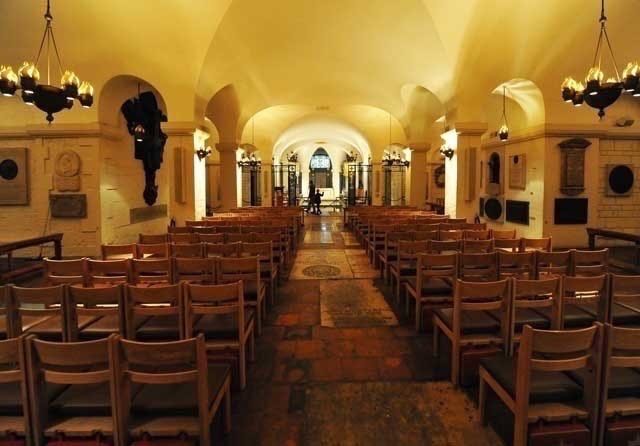

Passing now into the crypt of St. Paul’s, down a flight of steps in the transepts on either side of the dome area, you come to a spacious vault.

In the old St. Paul’s, this area was known as the Church of St. Faith, and it was here that books and valuables were stored by the booksellers of Paternoster Row, who thought that their products would be safe from the Great Fire of 1666.

Unfortunately, their faith was not rewarded, and the books went up in flames. It was said that the ashes from these books scattered as far away as Eton, 40 kilometers (25 miles) west of London.

This crypt is now used to hold the tombs and memorials to prominent figures from British history.

Here is a memorial slab to Sir John Goss, an English organist who composed an anthem for the Duke of Wellington’s funeral in 1852; the first lines of the anthem can be seen on the slab.

Here is also a simple tomb of the cathedral’s architect, Sir Christopher Wren. He was buried here after he died in 1723 at the age of ninety-one.

His tomb is covered by a unassuming black stone plaque with an inscription written by his son, also named Christopher.

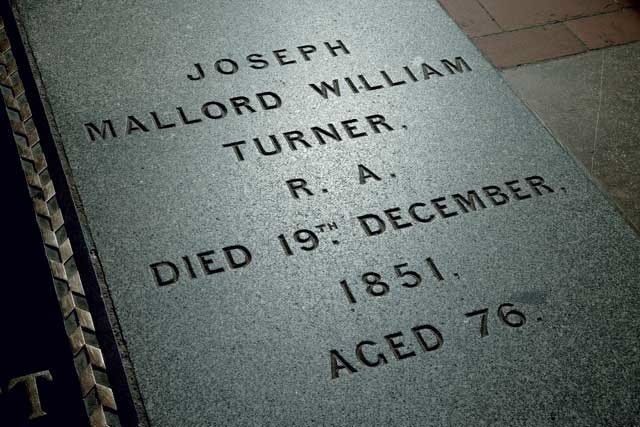

Surrounding Wren’s tomb are the memorials and tombs of English painters including that of the famous landscape painter, J. M. W. Turner.

One of the famous military heroes buried in the crypt of St. Paul’s is Arthur Wellesley, the 1st Duke of Wellington.

Compared to other tombs and monuments within St. Paul’s, the Duke of Wellington’s tomb is unassuming but grand, which it was said, reflected the character of the man when he was alive.

The floor here is inlaid with mosaic, which is believed to have been made by the convicts of Woking prison, 45 kilometers (28 miles) southwest of London.

Wellington had an impressive military career and he became British Prime Minister twice. He also remained Commander-in-Chief of the British Army right up until his death in 1852 at the age of 82.

Wellington is most well known as the general who led British and Prussian forces in the defeat of Napoleon’s army at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

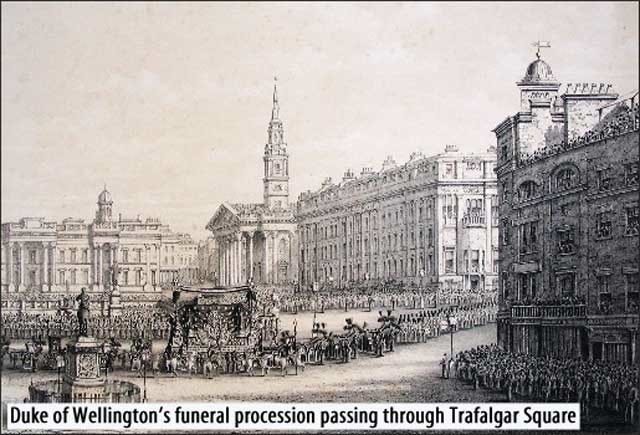

The Duke of Wellington was well loved by the general public and less than a month after his death preparations for the funeral were already being carried out on the St. Paul’s Cathedral floor.

The first thing that was done was to clear the cathedral floor for the workmen to carry out their jobs without damaging any of the statues and other objects. Work began with 200 workmen increasing to 1,500 by the second week. Sometimes these workmen would work 16-hour days to get the interior design and temporary construction done in time for the Duke’s funeral.

As the winter nights were drawing in, the workmen in St. Paul’s would find it difficult to see. As a solution temporary gas pipes were laid the length of the nave. These pipes had a series of gaslights placed along them and when lit it gave a theatrical atmosphere to the interior of the cathedral. The sounds of the hammer were heard morning, noon and night amplified by the large space of the cathedral as the cracks and bangs echoed from wall to wall.

As the day of the Duke’s funeral became closer, the workmen doubled their efforts to complete the work in time, working through both nights of November 16 and 17, 1852. At 6 a.m. on Wednesday the 18th the workmen were so exhausted that the Dean of St. Paul’s, Henry Milman found them resting and sleeping on the cathedral floor rather than their bedding.

The work these men completed was the erection of temporary wooden galleries much like the ones seen at modern sports stadiums. There were also a number of temporary gaslights installed throughout the cathedral that had been placed as high as the Whispering Gallery in the central dome; it was said that there were many thousands of gaslights installed in the cathedral. On the same day that the workmen had finished the job, the state funeral of the Duke of Wellington began.

The Duke of Wellington was well-loved, and it was said that a million people lined the parade route to pay their respects to the old war hero and statesman. The funeral coach was pulled by twelve magnificent black horses.

As the coffin was carried from the western door of St. Paul’s Cathedral along the nave, some 13,000 mourners who were in the cathedral went silent and at the same time those seated stood to pay respect. Among them were the entire membership of the House of Commons and the Lords, and members of the Livery Companies or guild organizations of the City of London. The coffin was followed by the choir of St. Paul’s Cathedral singing.

During the preparation of the Duke’s funeral, there was much discussion about how the Duke should be honored and where he should actually be buried. The tomb of Nelson already occupied the spot directly under the dome, and many thought that placing the Duke to either side of Nelson would be disrespectful to the memory of the “Iron Duke.” Even up to the day of the funeral this decision hadn’t been made and the Duke’s coffin was lowered from the cathedral floor to rest on top of Nelson’s sarcophagus in the crypt as part of the funeral service.

Up until 1858 the Duke of Wellington’s coffin remained on top of Nelson’s sarcophagus but was covered with a wooden construction.

There had been an extensive search across continental Europe by agents of the Government, looking for a large enough stone piece, fitting for the Duke’s sarcophagus.

After all the searching, the stone was not found on the continent, but back in England. A large piece of reddish granite called Luxullianite, weighing about 70 tons was lying in a field in a small village in the southwest of England.

The stone was cut and polished on the spot in the village of Luxulyan and its weight reduced to about 17 tons.

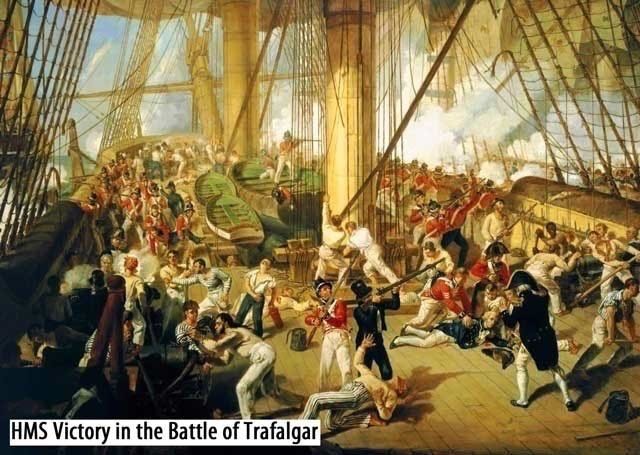

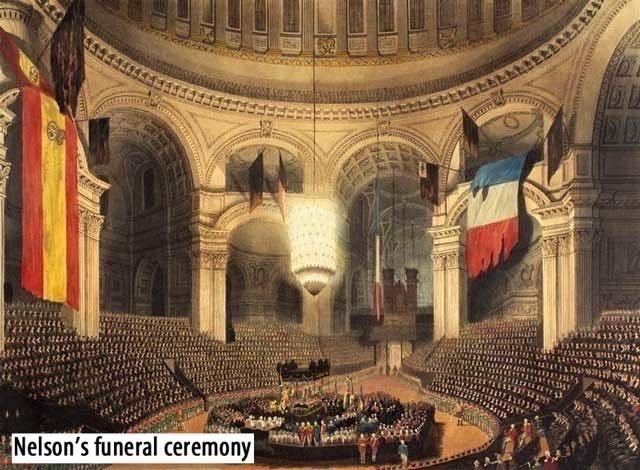

Next you see the tomb of the another famous military hero to be buried within St. Paul’s – Admiral Horatio Nelson.

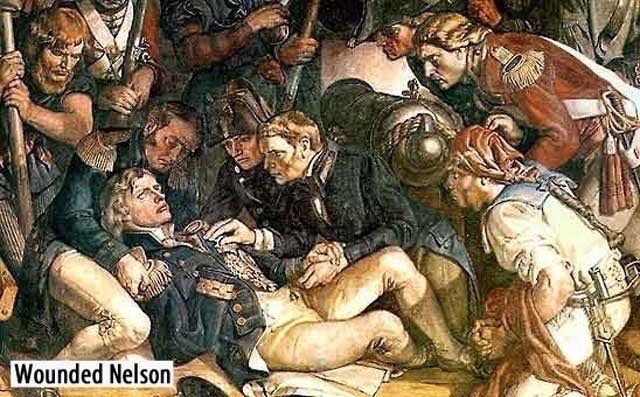

Nelson died in combat aboard HMS Victory during the Battle of Trafalgar on October 21, 1805.

He was one of the most prominent leaders of the Royal Navy during this engagement of the Napoleonic Wars in which Nelson and his fleet defeated the combined fleets of Spain and France without the single loss of a British ship.

Nelson had been mortally wounded by a sniper’s bullet that had entered his left shoulder and traveled through his spine. He died on-board the British flagship HMS Victory a few hours after sustaining his injuries, but survived long enough to hear the news that his fleet had won the battle.

Despite the tradition that sailors should be buried at sea, it was understood by the surviving officers of the battle that Admiral Nelson was regarded as a national hero even before his death, and they decided to preserve Nelson’s body in a barrel of brandy for the trip back to England.

Nelson was buried with the ceremony of a state funeral. The chief mourner was Admiral of the Fleet Sir Peter Parker and the procession consisted of eight thousand soldiers and sailors with hundreds of thousands of mourners lining the processional route.

Strangely enough, Nelson had already seen the coffin in which he would be buried. During the Battle of the Nile in 1798, British ships fought against the French fleet for control of Egypt.

During this battle the French flagship, Orient, exploded after her munitions caught alight. Captain Hallowell of the British ship Swiftsure had managed to get a part of the main mast of the Orient and had a coffin made from its wood for his friend Nelson. Hallowell sent it with a note saying, “When you are tired of this life you may be buried in one of your own trophies.”

Despite the strange gift it was said that Nelson accepted it gratefully; he even had the coffin placed upright with the lid on, in his own personal cabin. It was said that this coffin towered over him as he sat having dinner at his captain’s table.

The black marble sarcophagus of Admiral Nelson’s tomb here in the crypt of St. Paul’s was not actually created for Nelson. Cardinal Wolsey was one of the closest advisors of King Henry VIII who reigned 1509-1547, and it was the Cardinal who had the sarcophagus made for his own death.

The black sarcophagus was created by the Italian sculptor Benedetto Grazzini, but after Wolsey became the target of Henry VIII’s tyranny, the sarcophagus as well as all of Wolsey’s lands and property passed into the hands of Henry VIII. It was used briefly as a monument to Henry VIII by having a brass figure of the king placed on top of it. The sarcophagus remained in Wolsey’s Chapel at Windsor Castle until King George III was looking for a burial ground for the British royalty because Westminster Abbey was becoming overcrowded with about two thousand people interred there.

It was decided that the black sarcophagus could be used for Admiral Nelson’s remains and would also make way for a new burial-ground for the royals.

The sailors of HMS Victory who had survived the battle accompanied Nelson’s coffin in the funeral procession. After the coffin was lowered into the sarcophagus the sailors who had carried the torn flag of HMS Victory with them were supposed to fold the flag as part of the ceremony and place it on a nearby table. Instead, the sailors tore the flag to pieces so that they could claim a souvenir of the event and to remember their beloved leader.

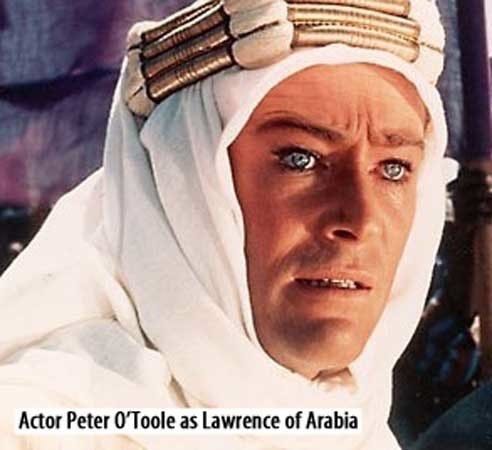

Here on the wall is a bust memorializing Lawrence of Arabia. During World War I, T. E. Lawrence was a British army liaison officer who raised and led an Arab force against the Ottoman Empire across the Middle East.

His fame across the Western world was immortalized by the actor Peter O’Toole who played him in the 1962 British epic film “Lawrence of Arabia.”

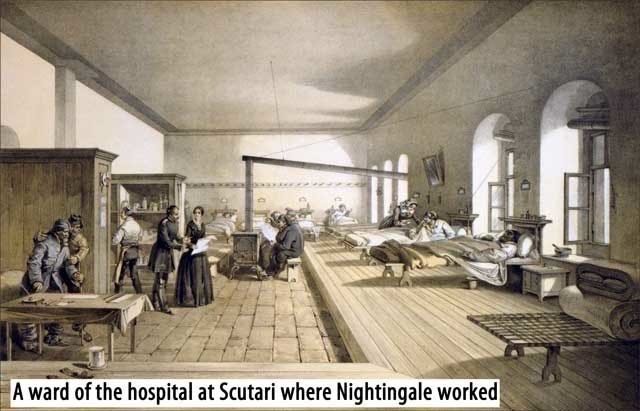

Here is also a memorial slab dedicated to Florence Nightingale who is known as the founder of modern nursing.

During the Crimean War in 1853-56, she served as a nurse in the field hospitals and helped improve the conditions and logistical procedures of the hospitals. She gained the nickname “The Lady with the Lamp” due to her many night-time rounds she made in the hospitals.

After the war she became a prolific writer and wrote numerous books on social reform and medical practice. She died in 1910 at the age of 90.

Let’s now exit the crypt, go back up and then up again.

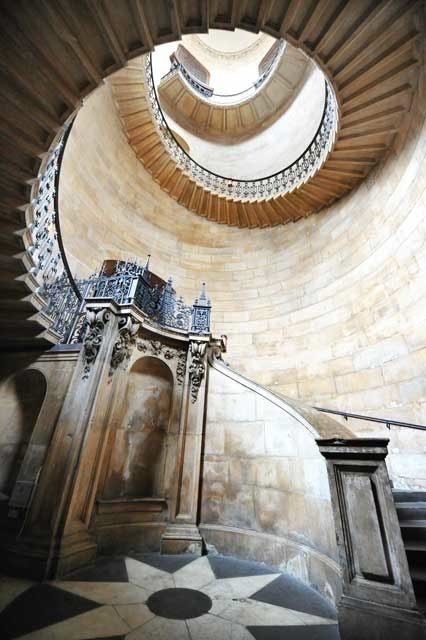

Another curious architectural feature of St. Paul’s Cathedral can be found if you climb 257 steps to the dome. The first level is called the Whispering Gallery.

It is called this due to an unusual acoustic phenomenon. The slightest whisper from one side of the gallery can be heard clearly on the other side of the gallery even though the perimeter of the space is more than 42 meters (138 feet). Any slam of a door is said to sound like the sound of thunder within the Whispering Gallery.

From the Whispering Gallery you can get a magnificent view of the cathedral floor below.

The floor directly below the dome has a large brass plate at its center.

This brass plate is surrounded by three perfect circles; the largest one mirrors the exact perimeter of the dome.

The Whispering Gallery is also the best place to view the paintings in the dome’s interior painted by James Thornhill.

The paintings depict a series of scenes in the life of St. Paul, starting with his conversion to Christianity near Damascus in modern day Syria and ending with him being shipwrecked near Malta.

It was said that James Thornhill had narrowly escaped death while carrying out the painting of the cupola.

One day while he was deeply concentrated on his work, Thornhill had finished touching up one of the heads of the apostles and decided to step back along the wooden scaffold to get a better view of his brushwork. While one of his friends was talking to him on the scaffold, Thornhill continued to step further back from the work, forgetting that the scaffold had no handrails along the side of it.

Seeing that Thornhill was just about to step off the scaffold and to a certain death, his friend grabbed a nearby brush full of paint and covered the delicate brushwork of Thornhill’s. With his quick thinking, Thornhill’s friend had saved his life as Thornhill immediately rushed back from the edge of the scaffold to save the painting from his friend’s seemingly crazy actions.

The Golden Gallery, 271 steps further up from the Whispering Gallery and above the Stone Gallery, is the smallest of the galleries and runs around the highest point of the outer dome. At 528 steps and 85 meters (279 feet) up from the cathedral’s floor, it is not easy to reach, but, as a reward, you will be treated to panoramic views of London.

But before you exit, please be informed that, as well as a working cathedral, St. Paul’s has been used as a movie location. Recently, the Geometric Staircase, to your right, featured in the Harry Potter movie “The Prisoner of Azkaban” and can be seen as the Divination Stairwell in the movie.

Now looking around outside, behind the Cathedral in St. Paul’s Churchyard, you will notice a statue with a gilded representation of St. Paul at the top.

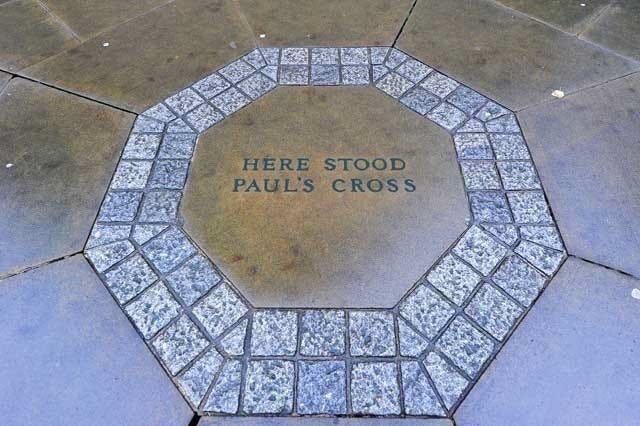

Just a few steps away is a small inscription on the pavement stating, “Here stood Paul’s Cross.”

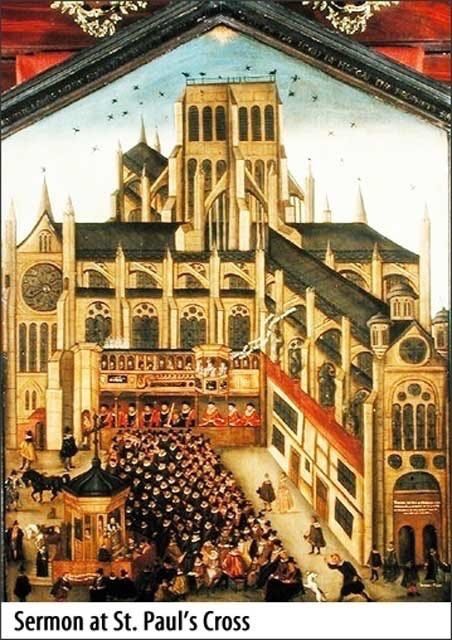

Paul’s Cross was an open-air pulpit that from the earliest times was traditionally seen as the place for the discussion of public news and orders. In 1259, it was here that King Henry III called for a general assembly to be made where certain Londoners were gathered at the Cross to swear their allegiance to Henry.

But let’s talk now about the cathedral’s history.

The first mention of a Christian building on this site, at the top of Ludgate Hill, the highest point in the City of London, was in 604, when a monastery was built here and dedicated to St. Paul.

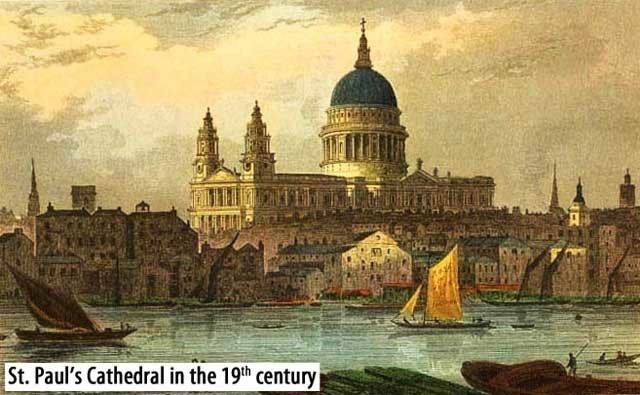

The current building was built between 1675 and 1710 after the Great Fire of London in 1666 destroyed the old cathedral.

The Great Fire started in a bakery on Pudding Lane and spread quickly throughout the city. A diarist of the time called John Evelyn noted that he had witnessed the repair scaffolds of the old St. Paul’s catching alight. By the next day, the stones of St. Paul’s began to explode from the heat, and large chunks of stone were seen shooting from the building. The lead from the building had melted from the heat and was seen running in the nearby streets.

The Great Fire lasted for five days and nearly all of the City of London burnt to the ground. During the Great Fire the pavements near St. Paul’s were so hot, and the area so blocked with collapsed buildings that no fire fighting aid could be given to the burning St. Paul’s.

At this time as well as today, St. Paul’s was used to inter prominent figures in tombs when they died. As well as completely destroying the cathedral all but one of the old tombs were destroyed, as well.

Although the cathedral was in ruins the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Sancroft, continued to preach in a patched up part of the ruins.

These sermons by the Archbishop still drew enormous crowds despite the condition of the cathedral; however nothing of significance was done to repair the cathedral until 1673.

It was decided by the new building’s architect, Sir Christopher Wren, that there was no chance to repair the old building. Wren began the new construction by clearing the site of any rubble and surviving structure. Some of the surviving walls were dangerously unstable and rose 24 meters (79 feet) into the air. A side of the central tower even rose 60 meters (197 feet) into the air.

To remove the surviving walls Wren used gunpowder and even a massive battering ram – a heavy beam of wood to knock down walls, based on a Roman design. However, it was noted that an unfortunate incident during the gunpowder blasting had put an end to its continuation. A small charge had been placed in the ground with not enough earth to cover it, and when this charge exploded it sent a large stone through a window of a nearby building that almost hit a group of women working inside. Later a passer-by was killed by flying stones after gunpowder had been used in an attempt to destroy the central tower.

After this, Wren was forced to use only a battering ram in the destruction of the surviving structure. Wren had famously stated that, “I build for eternity” and this was seen in his excavation of the ground around the site, through Norman and Saxon graves, searching for a stable foundation.

The first stone of the building was laid by Sir Christopher Wren on June 21, 1675, but unlike other later engineering projects in London it was done with no ceremony.

The story goes that after Wren had surveyed and drawn the circle for the beautiful dome on the ground, he asked a workman to get a stone to mark the exact center of the circle. The workman returned from a rubble pile of the old cathedral with a small fragment of a tombstone that stated in Latin “RESURGAM,” which translates to “I shall rise again.”

The new St. Paul’s Cathedral took 33 years to build. The last stone of the Cathedral’s structure was laid on October 26, 1708 by two sons named after their fathers, Christopher Wren and Edward Strong, the son of the master mason.

The first service had already been held in 1697 – a Thanksgiving for the Peace after the Treaty of Ryswick, which ended the Nine Years’ War between France and the alliance of England, Spain, the Holy Roman Empire and the United Provinces. This Treaty also seated Protestant William III of Orange firmly onto the English throne after the overthrow of James II in 1688.

Despite his desire to attend the opening service of St. Paul’s Cathedral William III was persuaded by his advisors to not attend. At this time there was still a battle between Catholicism and Protestantism for the English throne; the English court, now Protestant, feared that armed Catholic supporters of the deposed James II may find a way to hide in the crowds of three hundred thousand people that would line the processional route.

During building, Sir Christopher Wren had to overcome many obstacles and interference from the committee that oversaw the construction of the new cathedral and controlled Wren’s actions.

After the main structure of the building was complete the interior of the building and other minor designs had to be created. During one of the meetings the committee suggested that Wren should surround the church and its grounds with a wrought iron fence rather than a hammered iron fence.

Although it may seem rather minor, this argument turned into a serious dispute between the committee and Wren. Despite Wren’s arguments that hammered iron could be made more decorative than wrought iron, the committee overruled Wren and a wrought iron fence was chosen. It was Wren’s idea that the hammered iron fence would be low to the ground and decorative rather than the high fence of the committee that broke up the view of the Portland stone walls of the cathedral.

Another interesting point on which Wren did not agree with the committee was the decoration of the internal dome of St. Paul’s. Originally Wren wanted to use mosaic as a medium, but again he was overruled by the committee members who gave over the decoration of the internal dome to the English painter James Thornhill.

The committee complained continually of deliberate delays in the construction by Wren and accused the architect and the master mason of corruption. Although Wren was only given a salary of £200 a year, about $40,000 a year in today’s money, the committee would often withhold part of Wren’s salary in punishment for his opposition to the committee’s suggestions.

The chief building material of St. Paul’s Cathedral is Portland stone, and St. Paul’s was one of the first buildings in London to use this stone. It would later be used almost exclusively in Victorian engineering projects, most notably at Tower Bridge.

Of course, a very large amount of stone was required for the building of St. Paul’s and the mines on the Isle of Portland situated on the south coast of England were devoted entirely in producing worked stone for the cathedral. There was even a special order given by King Charles II that no Portland stone could be removed for any purpose other than the construction of St. Paul’s without the permission of Sir Christopher Wren.

The problem with Portland stone is that it is vulnerable to staining and in the previously dirty atmosphere of London’s past, the stone had become covered in ash and soot. After a 15-year program of cleaning and repairing, St. Paul’s was restored to its former glory in 2011, in time for its 300-year anniversary.

It was said that if St. Paul’s were to be cleaned to its original condition, Londoners might be blinded by the brightness of the stone as the sun reflects on it. This does not appear to have happened.

But back to the past. In 1718, a pamphlet was circulated from an anonymous source claiming that Wren’s workmen had stolen building materials and had deliberately cracked the newly cast bells before their installation. That same year Wren was removed from his place as architect of St. Paul’s and his position as Surveyor of Public Works.

Wren was 86 years old when he was fired, but he used his newfound time wisely by taking up philosophical and religious studies. It was said that despite his retirement to nearby Hampton Court, Wren would ask to be carried each year into London to see the beauty of his cathedral.

The entire cost of the building of St. Paul’s Cathedral was said to be roughly £737,000, which in today’s currency is roughly $150 million. It has been argued that the completeness and unity of the architecture of St. Paul’s can be attributed to the single service of Sir Christopher Wren and his master mason, Thomas Strong throughout the entire construction.

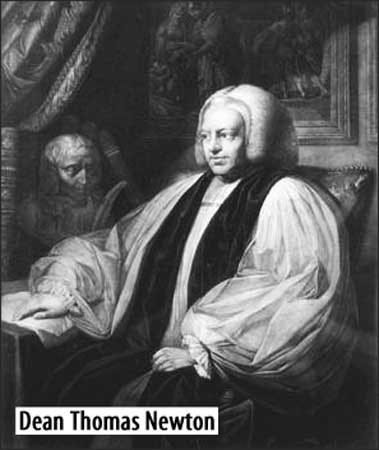

At its completion the clergy of St. Paul’s were very reluctant to place monuments within the building. However, the Dean of St. Paul’s, Thomas Newton who served between 1768 and 1782 expressed a wish to have his tomb placed within the new cathedral.

At the time of Dean Newton’s service St. Paul’s was fully completed, and it is likely that Dean Newton wanted to be the second person honored with a tomb in the new cathedral after the cathedral’s architect, Sir Christopher Wren was the first to be buried in the cathedral.

However, his wish was never realized as it was seen as too self-serving, and he was buried in the nearby church of St. Mary-le-Bow.

St. Paul’s Cathedral is still a major place of Christian worship in England and despite the number of modern skyscrapers being erected in London, still remains a dominant feature of the London skyline.

Travel guides that show you around and tell stories, not just history.

Dear Traveler, please review this book, we truly appreciate your feedback.

Are you exploring famous landmarks in cities around the world? Are you looking for more insight than a typical guidebook provides you? Perhaps you would like your own personal tour guide but prefer to visit places at your own pace? Are you curious about how people lived in those palaces and castles? Maybe you just want to understand people from different cultures better? Well, we have exactly what you need, we tell WanderStories™.

WanderStories™ is the best local guide for you, showing you around and telling stories of famous and interesting sights, in an e-book on your tablet, smartphone, or computer.

WanderStories™ travel guides are unique because our storytelling style puts you alongside the best local guide who tells you fascinating stories, while a wealth of high quality photos, historic pictures, and illustrations brings your tour vividly to life.

WanderStories™ travel guides are e-books that include lots of photos, maps, and illustrations and tell you the stories behind the history of the places you will visit, like the best personal tour guides would do. In fact, they do it so well that you can visit the most extraordinary places around the world without even leaving the comfort of your armchair. Wherever you are, you can experience the excitement of history being recreated around you as the story unfolds.

You will get to know how real people, emperors and sultans, concubines and eunuchs, slaves and executioners lived in the palaces you will visit; what gods the monks worshipped in these temples; how generals and soldiers, crusaders and gladiators fought and won…or died. You will learn about local traditions and customs, holidays and festivals, cuisine, even jokes.

Whether you’re at home, on your travels, or walking in the historic setting itself, WanderStories™ is the best personal, local guide on your tablet, smartphone, laptop, or computer.

We, at WanderStories™, are storytellers. Our mission is to be the best local guide that you would wish to have by your side when visiting the sights.

Our promise:

• when you visit a city with a WanderStories™ travel guide you will have the best local guide at your fingertips

• when you read a WanderStories™ travel guide in the comfort of your armchair you will feel as if you are actually visiting the best sights in the city with the best local guide

Please get WanderStories™ travel guides at: wanderstories.com

Please subscribe to the FREE WanderStories™ travel e-magazine, Armchair Travel Guide at: wanderstories.com/travel-magazine

Sample from: London Tour Guide Top 10

Copyright © 2015 WanderStories

Photos and illustrations provided by WanderPhotos™

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or distributed in any form by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems without permission in writing from the publisher.

Disclaimer. Although the authors and publisher have made every effort to provide up-to-date and accurate information, and have taken all reasonable care in preparing these publications, they accept no responsibility for loss, injury or inconvenience sustained by any person relying on or using our publications, and make no warranty about the accuracy or completeness of their content and, to the maximum extent permitted, disclaim all liability arising from their use.