Topkapi Palace

Blue Mosque

Grand Bazaar

Dolmabahçe Palace

Chora Church

Süleymaniye Mosque

Basilica Cistern

Archaeological Museum

Galata Tower

History of Istanbul

Turkish Hammam

Traditional Turkish Handicrafts

Turkish Holidays and Festivals

Turkish Traditions and Customs

Islam in Turkey

Turkish Humor, Jokes, and Anecdotes

Welcome to the WanderStories™ tour of the top 10 sights in Istanbul: Topkapi Palace, the Hagia Sophia, the Blue Mosque, the Grand Bazaar, Dolmabahçe Palace, the Chora Church, the Süleymaniye Mosque, the Basilica Cistern, the Istanbul Archaeological Museum, and the Galata Tower. We are now ready to take you on your personal tour of these world famous landmarks.

We will also tell you additional stories about Istanbul’s history, Turkish traditions and customs, holidays, Turkish hammam, cuisine, jokes, Islam in Turkey, and traditional Turkish handicrafts.

We, at WanderStories™, are storytellers. We don’t tell you where to eat or sleep, we don’t intend to replace a typical travel reference guide. Our mission is to be the best local guide that you would wish to have by your side when visiting the sights. So, we meet you at the sight and take you on a tour.

WanderStories™ travel guides are unique because our storytelling style puts you alongside the best local guide who tells you fascinating stories and unusual facts recreating the passion and sacrifice that forged the beauty of these places right here in front of you, while a wealth of high quality photos, historic pictures, and illustrations brings your tour vividly to life.

Our promise:

• when you visit these top 10 sights in Istanbul with this travel guide you will have the best local guide at your fingertips

• when you read this travel guide in the comfort of your armchair you will feel as if you are actually visiting these top 10 sights in Istanbul with the best local guide

The city that we now know as Istanbul has been known by many different names throughout its long history. It was founded in 667 B.C.E. as Byzantium. Then, in 330, the Roman Emperor Constantine I christened it as New Rome. Later, it would come to bear his own name and be known as Constantinople, which was then rendered into Arabic languages as Kostantiniyye, which the Ottomans also adopted. The city was destined to finally be known in our modern age as Istanbul, derived from a Greek phrase meaning, simply, to the city.

So much has changed over the time those names spanned that it seems impossible they could possibly refer to only one city. Yet they do, and the city of Istanbul is still a vibrant place that treasures the artifacts of the various peoples who once lived here and knew it by such different names.

One phrase has also been used to name the city: “The City of the World’s Desire.” If judges could pick the most appropriate name for the city, perhaps they would choose this one, as it reflects most accurately how famous and how loved the city has been since antiquity.

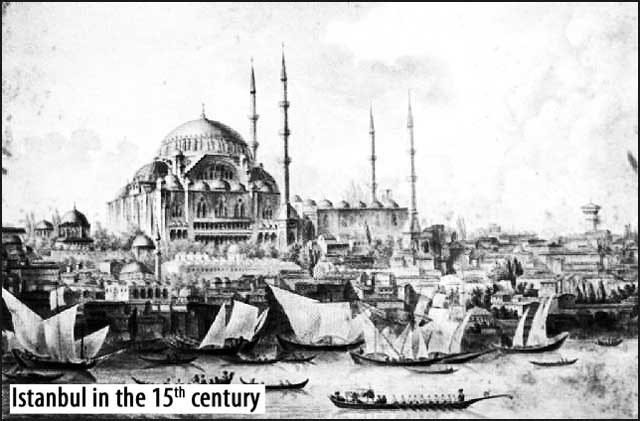

The face of Istanbul has changed considerably inside the modern nation. Justinian’s masterpiece, the Hagia Sophia, was turned into a museum and its wonderful mosaics were revealed to the world once more in 1935. Two bridges now span the Bosporus, and along with the historic skyline of the old city there are now also skyscrapers.

Today, the city’s importance in world history is indisputable, and it is difficult to believe that all of this long history concerns just one city. There is only one thing to do now – visit!

Let’s go!

Your guide, WanderStories

Once you have read this book please review it, we truly appreciate your feedback.

Please subscribe to the FREE WanderStories™ travel e-magazine, Armchair Travel Guide at: wanderstories.com/travel-magazine

Hagia Sophia (Aya Sofya)

Address: Ayasofya Meydanı, Sultanahmet

41°00'28.8"N 28°58'43.9"E

Upon entering the Sultanahmet area of Istanbul, you are essentially entering the summit of the first of the seven hills of Istanbul.

The Hagia Sophia and the Blue Mosque sit opposite one another on a large grassy park, shaded by a few scattered trees and complete with a fountain in the middle.

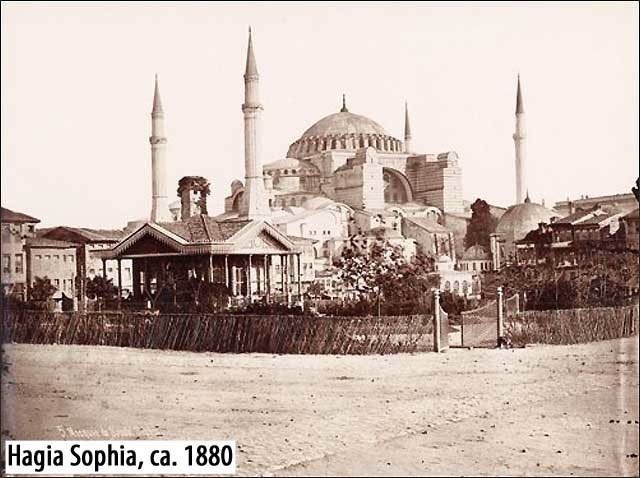

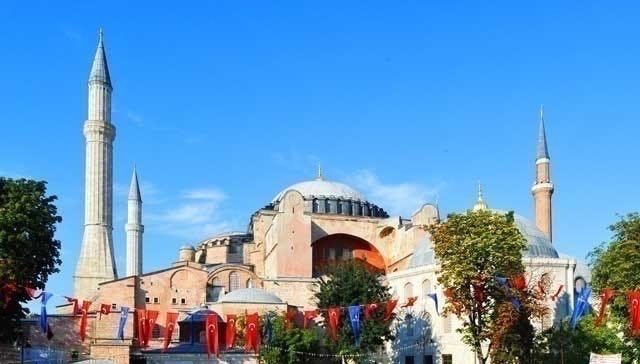

The Hagia Sophia is immediately noticeable due to its dusty rose color and immense central dome. It is a colossal structure and dominates the landscape.

Interestingly enough, there is photographic evidence that the Hagia Sophia once had horizontal stripes painted along its outside walls, which are not visible today.

The massive brick buttresses that support the huge dome are an unfortunate yet necessary addition, mostly from the 16th century, as they make the structure feel too heavy. Nevertheless, it still stands, which is of course the most important thing.

The Hagia Sophia, meaning Holy Wisdom, or Aya Sofya in Turkish, is an unrivaled monument in the city of Istanbul. No other structure in the city, ancient or modern, compares to its long history, magnificence, and influence.

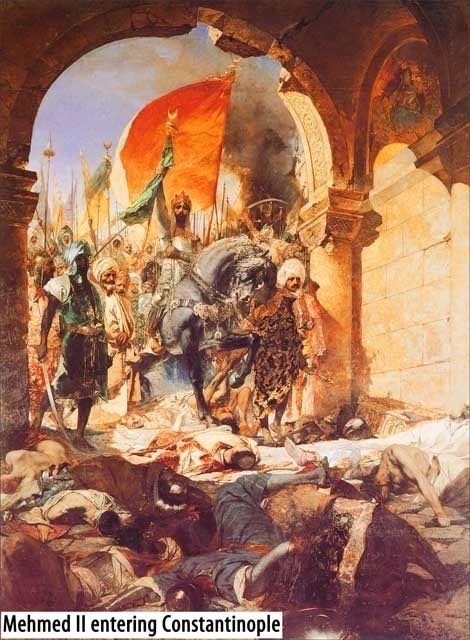

It represents the superb pinnacle of Byzantine architecture and is the first monument, which Mehmed II, the conqueror of Constantinople, walked into, thereby claiming the city as his own in 1453.

Through the centuries it has witnessed the fall of three empires – Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman, and the birth of the Republic of Turkey, and still it sits solidly atop the old city of Istanbul, proclaiming the rich history of its land. If only it could share its secrets with us, for one suspects that the Church of the Holy Wisdom is wise indeed, and a trip to Istanbul is hardly complete without paying our respects to this ancient monument.

Originally built and maintained as a church, the Hagia Sophia was first dedicated on February 15, 360 not long after the founding of the city of Istanbul itself in 330. However, this structure was destroyed during a fire caused by a riot.

The second dedication was on October 10, 415, yet this one was also burned down during riots.

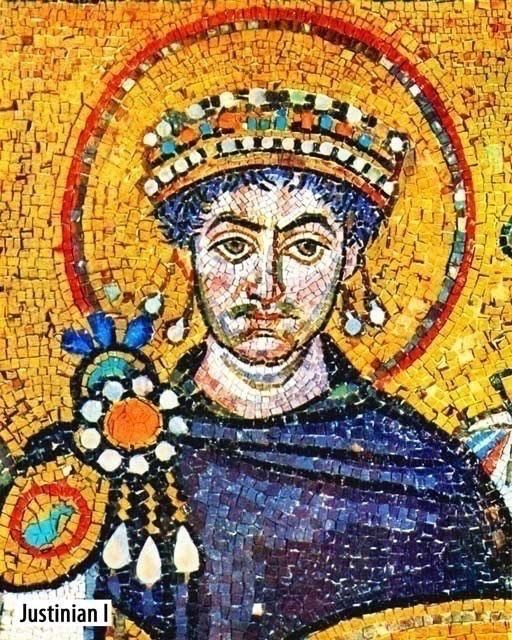

Finally, on December 26, 537, under the reign of Justinian I, it was dedicated for the third time, and the general structure of the monument we see today is the original of Justinian’s time. Justinian I desired his new Hagia Sophia to outdo all other buildings in the empire, and it is quite clear that he succeeded.

Hagia Sophia has been called the eighth wonder of the world by East Roman Philon as far back as the 6th century. It has been said that the Hagia Sophia changed the history of architecture forever. It remained the world’s largest cathedral for nearly a thousand years, until Seville Cathedral was completed in 1520.

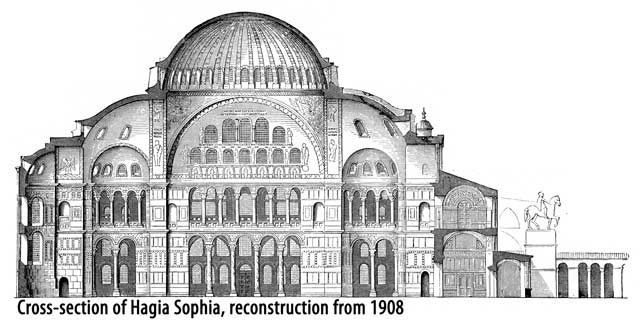

The initial two architects were Anthemios of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus, both of whom lived within ancient Anatolia. They were prominent and respected men in Byzantine society and, interestingly enough, were not known primarily as architects but as academics, and were probably chosen for the task in order to bring fresh insight to Byzantine architecture. The building the architects designed was remarkably similar to the building we see today except for the fact that the enormous central dome was much lower. This caused instability in the structure, and eventually there was a collapse of this central dome in 558 during an earthquake.

The architect who came to the church’s rescue was Isidore of Miletus’s nephew Isidorus the Younger. He increased the height of the dome, but made few other architectural changes. Yet the dome again suffered a collapse in 869 and then again in 989, at which time the famous Armenian architect known as Trdat was in charge of the renovations. Supports were added in 1317 and were strengthened again during the Ottoman era.

It was also shortly after the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453 that the minarets replaced the bell tower.

The last sizable restorative efforts were made in the mid-19th century by the Fossati brothers under Sultan Abdülmecid I, and then by the Byzantine Institute in the 1930s and 1940s under the guidance of Thomas Whittemore.

The Hagia Sophia is included, as part of the Historic Areas of Istanbul, in the UNESCO World Heritage List from 1985, and is visited by more than three million people every year.

The entrance is on the southern side, let’s start our tour.

Upon entering the inner grounds of the museum you can see some historical artifacts, which were unearthed around the area of the museum.

Let’s enter the Hagia Sophia underneath some of the huge supports.

One artifact, especially of interest, is the former entrance to the church, which stood in the same spot long before the Hagia Sophia, referred to as the Theodosian Church.

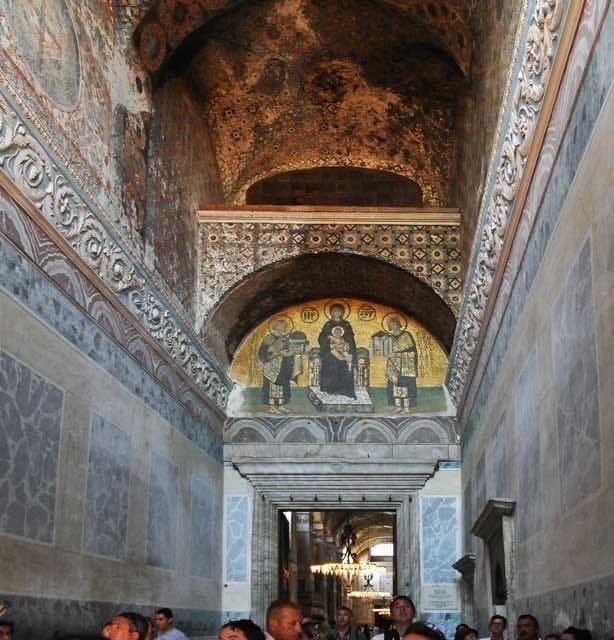

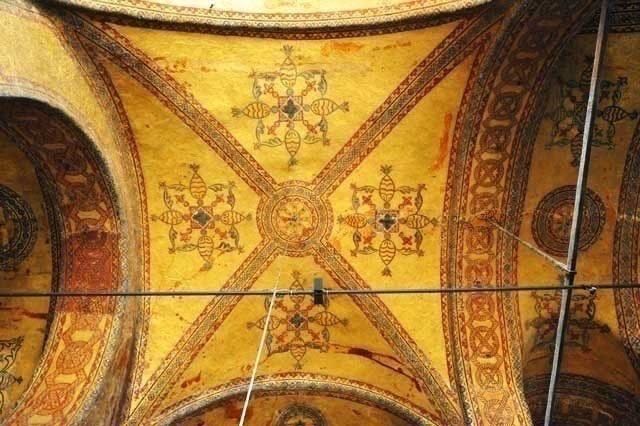

Through the door we walk into the narthex or entrance area, where you see the first mosaics when you look up to the ceiling.

These are mostly from Justinian I’s time and are therefore some of the oldest mosaics in the museum. You will later see how the same colors and geometrical patterns are repeated throughout the church.

Although the general architecture of the church hasn’t changed, what have changed quite a bit since Justinian I’s time are the interior decorations of the church.

When the church was first completed there weren’t many figurative decorations in the whole of the church, and the decorations mostly consisted of gold tiles and abstract, geometrical patterns. Since then, the mosaics have been changed several times, being alternatively more figurative, then completely non-figurative during a period of iconoclasm, and then figurative again when the Orthodox Church broke away from the Catholic Church.

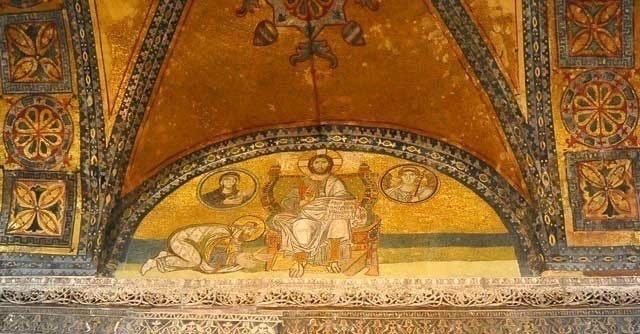

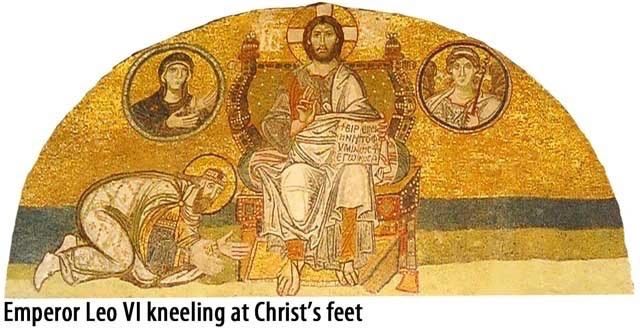

The decoration above the door into the nave, which is the central approach to the high altar, has the first figurative mosaic. Christ is seated on a splendid throne, with the Emperor Leo VI kneeling at his feet. In circular frames there also appear the Virgin and an angel. It is thought that this mosaic is from the 9th century, probably from Leo VI’s reign as emperor.

Leo VI produced something of a scandal during his time thanks to his numerous marriages. Three wives passed away before him, and he had still not produced a male heir. For this reason, he wanted to marry his mistress, Zoe, with whom he had already produced a male child, but a fourth marriage was usually not allowed by the church at the time. Eventually he gained permission, and his formerly illegitimate son became Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus.

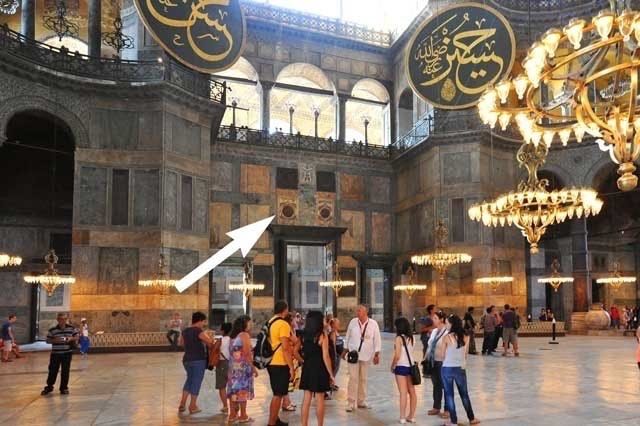

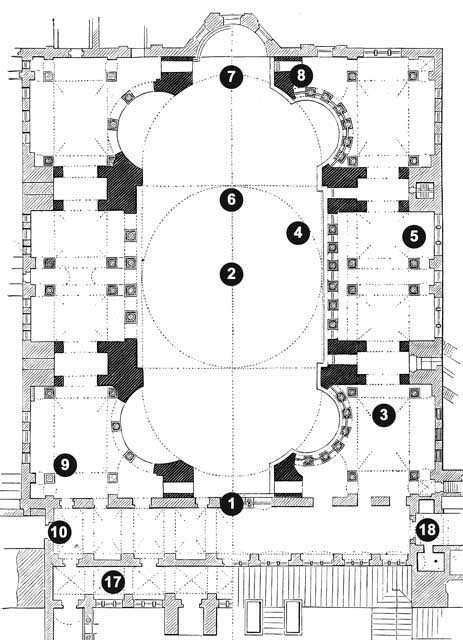

The impressive door underneath this mosaic you pass through is called the Imperial Gate (No. 1 on the plan of the ground floor). There are many other entrances to the nave, and many of the doors are of note as they are from Justinian I’s time, however this is the largest and most ornate. As its name suggests, it was through this door that the emperor passed when he attended church services.

A Byzantine church ceremony was long and elaborate, and included a number of different processions, and so it is no wonder that the emperor should have a specific gate for himself and his entourage.

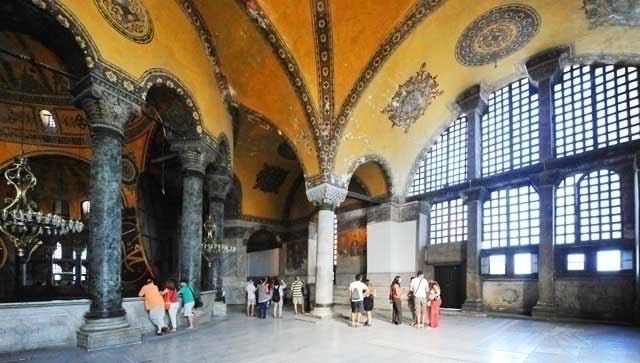

Let’s now talk about the general architecture of the Hagia Sophia. As said before, the basic structure of the Hagia Sophia that we see today has not changed too significantly since the third building of the church by Justinian I in 537 except for a few elements, most notable of which are the large supports that distribute the weight of the dome.

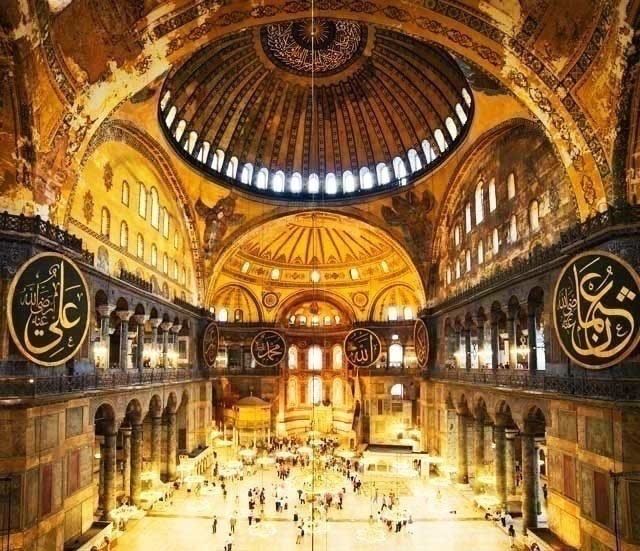

You can see the massive central dome that is 55.6 meters (182 feet) from floor level, and around 31 meters (102 feet) in diameter, although this varies as the dome’s perfect circle has warped slightly due to its many repairs.

The cupola (No. 2), which when looking up appears as the small inner circle at the center of the dome, is carried on four spherical triangular pendentives, an element which was first fully realized in this building.

And then below these are four massive piers.

These piers do not stand alone in the center of the church, but are blended into the galleries supported by columns of verde antique, the wonderful green stone that was so prized in the ancient world.

Between the massive piers and above the gallery of columns are two tympana – semi-circular decorations. Each tympanum has twelve visible windows, and the half domes and central dome are also punctuated by windows. These windows are in part what is so remarkable about the Hagia Sophia.

Due to the weight of the central dome, it is surprising that any windows at all could have been incorporated into the structure. But with the ribbing in the dome, the weight is guided around the windows. This extraordinary architectural feat gives the feeling that the domes are merely hanging in the air, unsupported, something that has been commented upon by many observers throughout history.

Walking now into the central area, even with the crowd of tourists, you can see why the church has never failed to impress during its incredibly long history. Every aspect of the church seems to exist in a harmonious relationship to all others, down from the enormous central dome floating above its windows, past the half domes and tympana, and along the columns all the way to the floor.

It is truly breath-taking, and we can understand how Justinian I reportedly exclaimed, upon seeing his new church, “Solomon, I have outdone thee!”

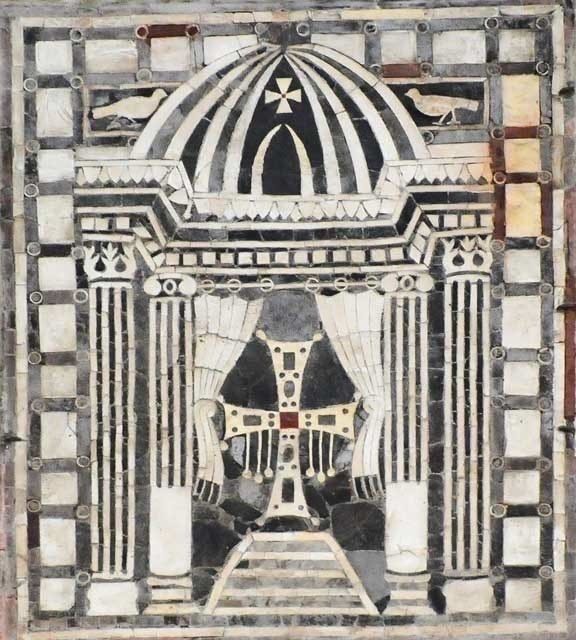

If you turn around now to look back at the Imperial Gate, you see some fascinating marble decorations above it.

The first, mainly in black and white, is a small panel showing a ciborium, or curtained structure, which covers the altar in a church, inside the curtains of which is the altar and a cross.

Below this you can see stylized dolphins chasing squid. You can see other such panels around the church; often they depict large ovals of red porphyry stone surrounded by, interestingly enough, heart shapes.

Looking to the left and right of the Imperial Gate you can see the huge marble urns that are from the reign of Murad III, who brought them from Pergamon, today’s Bergama in Turkey. They were once filled with water that worshippers could drink to satisfy their thirst after their prayers.

Let’s now walk briefly along the right vestibule (No. 3). When you look up and around the aisles in this area, you see they have largely preserved the original geometric mosaics.

In the left vestibule you can see the same mosaics, but due to other structures outside the windows it is significantly darker and more difficult to appreciate them.

After coming back into the central nave, you can see an interesting pattern on the ground, with a small chain around it to ensure it won’t be stepped upon. This large pattern of circular granite and red and green porphyry pieces embedded into the floor is what is called the Omphalion, or omphalos, meaning the center of the world (No. 4). Most likely the shapes were cut from columns that had passed their prime and could therefore be put to other uses.

These kinds of markings on the ground usually indicated an area of importance inside the church, and this particular area marks the place where either Byzantine emperors were crowned or where they sat during church ceremonies. It is not known for sure which is true, it could be both, as well.

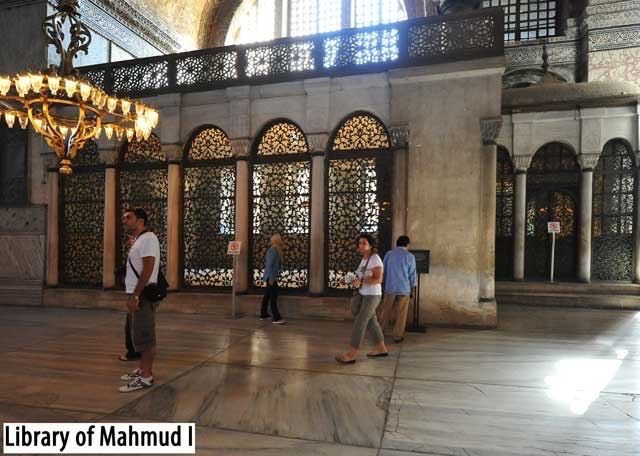

Beside this you can see an elegant library built by Mahmud I in 1739 (No. 5).

Standing now in the middle of the nave (No. 6), you can only wonder what the Hagia Sophia would have been like shining with the golden mosaics with which the Byzantines had originally adorned it.

In Justinian I’s time, the central dome would have had a large cross upon it, and each rib of the dome would have the alternating cross-and-diamond pattern that you can still see today.

Later, probably in the 14th century, an enormous bust of Christ was added in the center of the large dome, which is now gone.

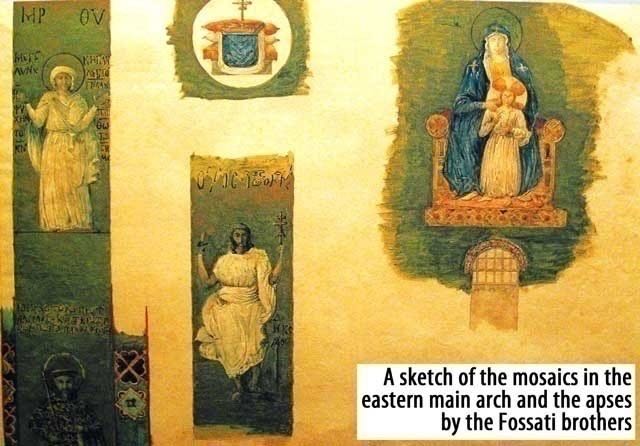

Scholars have determined that the figurative mosaics in the nave would have once amounted to the following: the large bust of Christ in the central dome, the Virgin and Christ in the apse, the two Archangels Gabriel and Michael below in the arch, the apostles of Christ in the opposite arches, and sixteen prophets in the tympana.

Not many of these are still around, but let us go on to describe the mosaics that are still here, starting with the apse mosaic.

Here, the Virgin sits on a jewel-encrusted bench with Christ on her lap. She is in robes of dark blue and Christ in gold. This mosaic comes from the 9th century and marks the beginning of the return to figurative mosaics in the Hagia Sophia.

Underneath this mosaic, in the arch, is the figure of the Archangel Gabriel, looking impressive in multi-colored feathers.

There is an inscription in Greek, and although it is largely destroyed, historians have determined that it once celebrated the triumph of the Orthodox Church and the reinstitution of figural art.

Opposite the Archangel Gabriel used to stand the Archangel Michael, of whom nothing remains.

You can also see the four seraphim or perhaps cherubim – winged mythical beings, in the pendentives of the main dome. In the Bible the characteristics of cherubim and seraphim are the same, and so it is not known which they are.

Two of these are original, and the other two are painted during the Fossati restorations.

Only recently has the face of one of the seraphim been revealed to the public for the first time in hundreds of years.

In this mosaic, the six wings sail out and around a face that seems thoughtful and serious, as if the angel were watching and judging us.

These mosaics most likely date from the 14th century, however, it is possible that they are copies of earlier versions of the same angels.

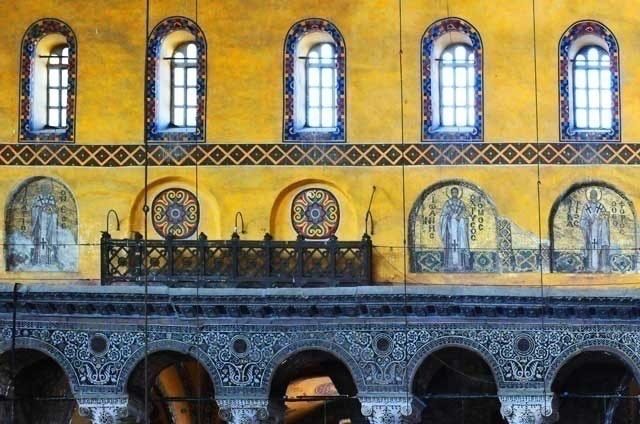

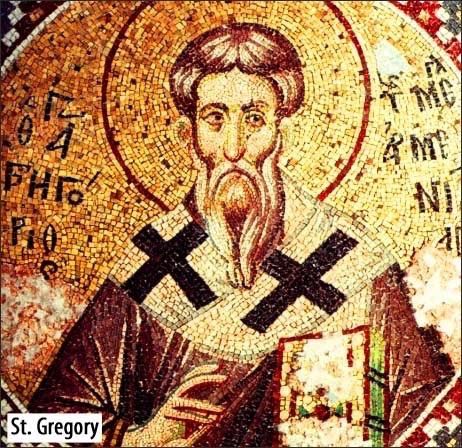

Along the bottom of the north tympanum you see the mosaics of three bishops who are also known as saints.

These are St. Ignatius the Younger, St. John Chrysostomos, and St. Ignatius Theophorus. These are all that are left of the sixteen which once adorned both tympana.

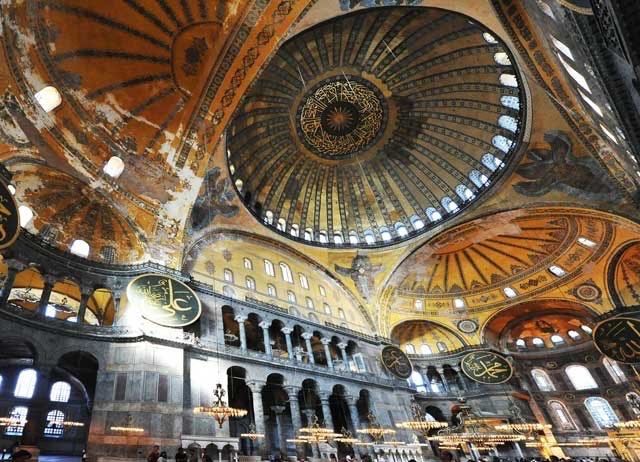

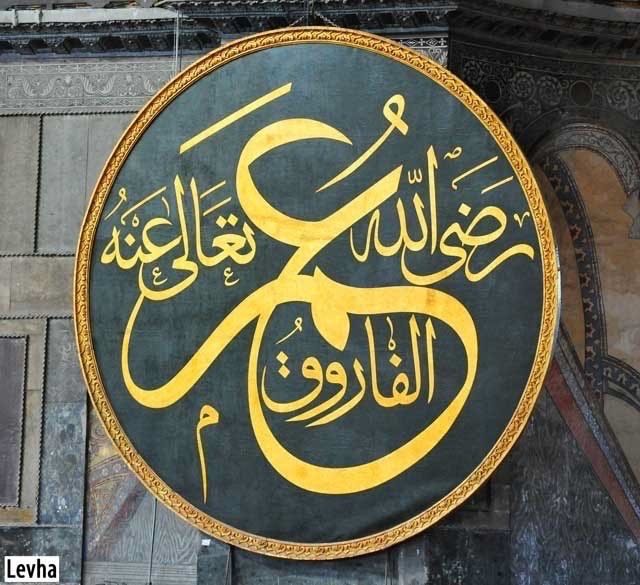

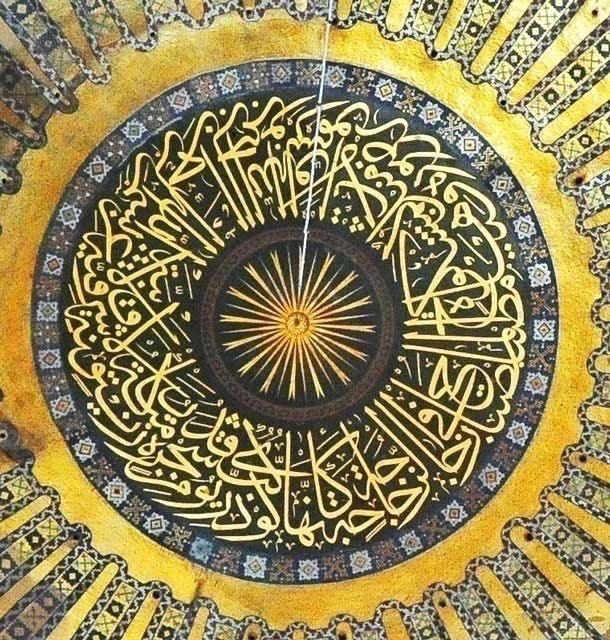

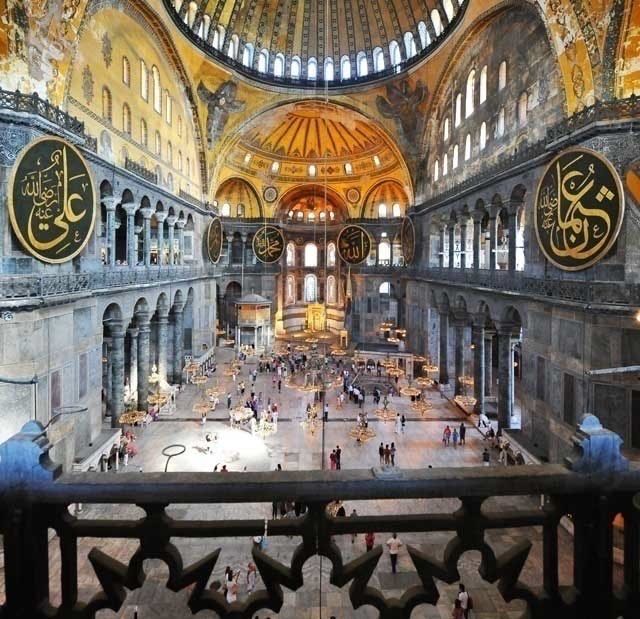

Of course, the other decorations most prominently seen from the middle of the nave are the large, circular roundels or levha, the framed calligraphic inscriptions. The famous calligrapher Mustafa Izzet Efendi made these, and also the calligraphy around the central dome in 1849.

The levha depict the names of Allah, the Prophet Muhammad, the first four caliphs, and the grandchildren of Muhammad.

Around the dome is a verse from the Koran, Sura XXIV: 35, which describes Allah as the light that illuminates all things, and also mentions this light being neither from the east nor the west; a fitting addition for a structure which can also be described as such.

Many people regard the levha as harmful to the internal harmony of the structure. They do, indeed, disrupt the lines taking the structure of the roof down to the piers, yet they also mirror the circular structures of the domes above.

Let us now pause for a moment and talk about the marble columns and wall covers of the structure.

The marble and granite you can see came from all over the Byzantine Empire, and most were probably specially mined for the grand church. This is contrary to popular belief that the columns were taken from monuments all over the ancient world. A few, no doubt, are second-hand, but the majority appear to have never been used prior to the Hagia Sophia.

The white marble, used for some of the smaller columns and the floor, is mostly from Marmara Island, and it is still mined there today. The verde antique marble is most likely from Thessaly and has been extensively used for columns in the Hagia Sophia. The decorative marble used on the walls comes from places such as Tunis and all over Anatolia.

How the marble tiles were created is always intriguing; visitors are often surprised to hear that they are natural and not painted, except for the areas of restoration. They were made by cutting large blocks of marble in half, resulting in two blocks with mirror images, which were then placed side by side.

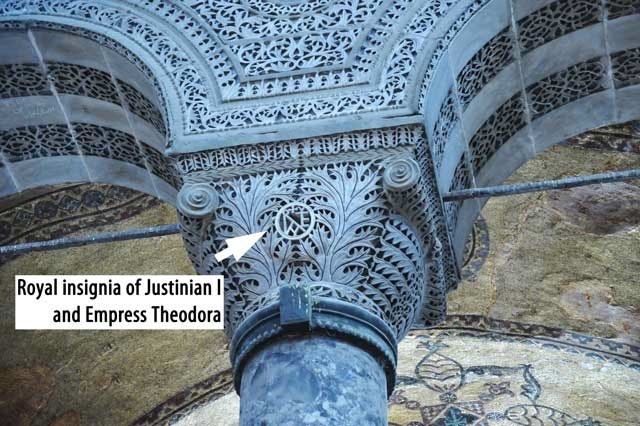

The capitals of the columns also deserve specific attention and are a unique aspect of Byzantine architecture. They have an amazingly intricate pattern including acanthus plant leaves and often the royal insignia of Justinian I and Empress Theodora.

Let’s walk toward the apse (No. 7).

You see the large minbar, the podium from which the imam preaches.

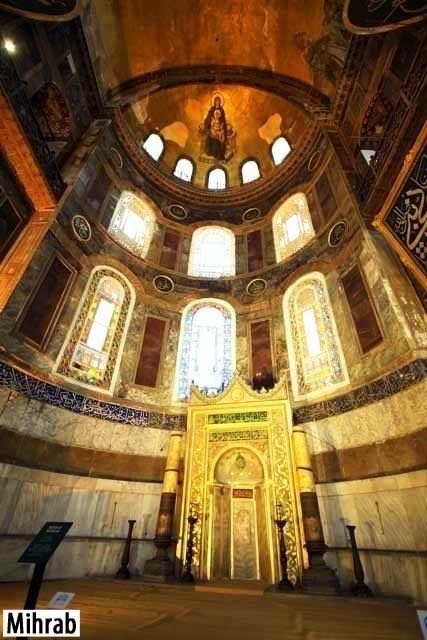

And also the mihrab, the niche, which points toward Mecca.

They are not so remarkable but are beautiful in their own way, and thankfully they do not detract from the architectural symmetry.

To the left of the apse, you can see the imperial lodge, which the Fossati brothers made for Sultan Abdülmecid I. It is quite lovely, and its gilded fence blends nicely with the rest of the structure.

The four platforms placed next to the piers from which the Koran was sung were commissioned by Sultan Murad III.

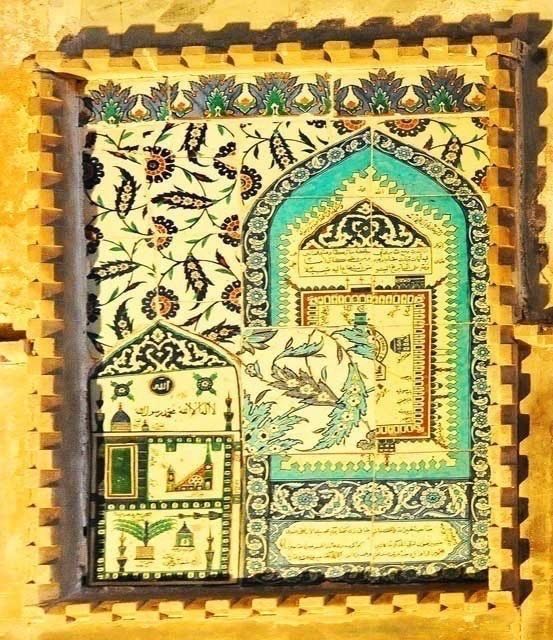

To the left and right of the nave, in small tunnels, you can see some Iznik tiles from the 16th and 17th century.

The tunnel on the right houses an especially interesting piece depicting the mosque of the Kaaba in Mecca (No. 8).

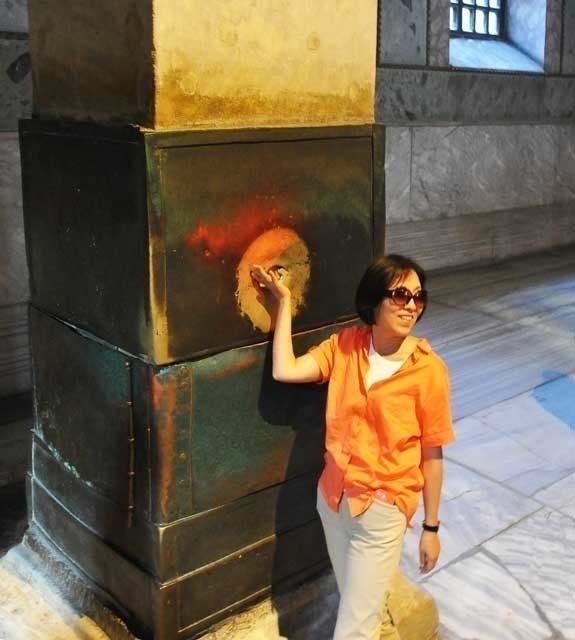

But before entering the narthex, still inside the main structure of the Hagia Sophia, you can see the Sacred or Sweating Column (No. 9), which has a wide metal band around it.

Legend has it that St. Gregory once appeared beside the column, and that therefore the column has healing properties.

You can see a hole that has been made in the column from the millions upon millions who have rubbed it, hoping to catch some of the healing water that is supposed to collect in the little hole.

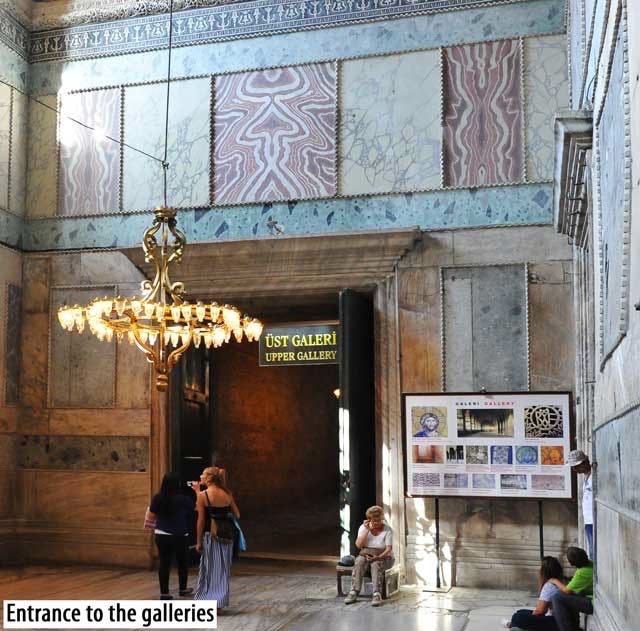

Let us now proceed to the upper floor. There is only one entrance to the galleries, and it is back by the main entrance, in the narthex (No. 10).

A sloped platform will eventually lead up to the galleries.

Up here, you first notice how most of the mosaics on the ceiling are gone and have been replaced by the Fossati restoration.

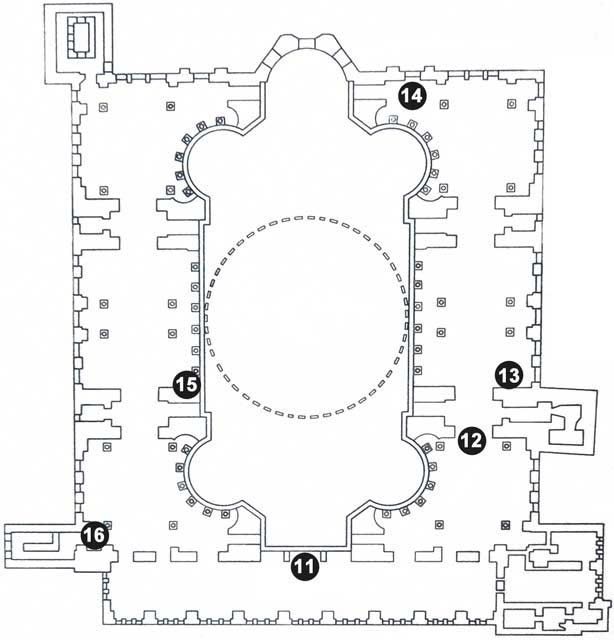

As you walk first to the right, you see on the floor a square frame, and at its top a green circle embedded into the floor, similar to the one you saw earlier by the Imperial Gate. This was the spot where the empress would sit on the throne and watch the church ceremonies (No. 11 on the plan of the galleries).

It is also from here that you notice a splendid view of the Hagia Sophia. Though the empress was consigned to the women’s quarters of the church, she must also have had the best view of the church ceremonies. Facing the apse, the whole of the Hagia Sophia is visible. You can see the highest point in the central dome, the apse, and floor, and so can appreciate the church’s true size and symmetry.

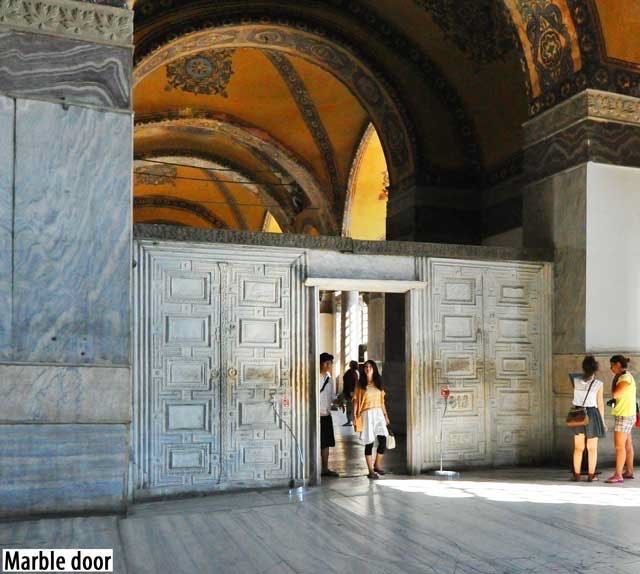

Next you come to a strange marble door (No. 12). Most likely this was not in the original design of the church and was moved here after the 6th century, which is when the door actually dates from. It was probably moved here to give the church council, or synod, some privacy during their meetings.

When you pass through this door, you see the other mosaics for which the Hagia Sophia is famous.

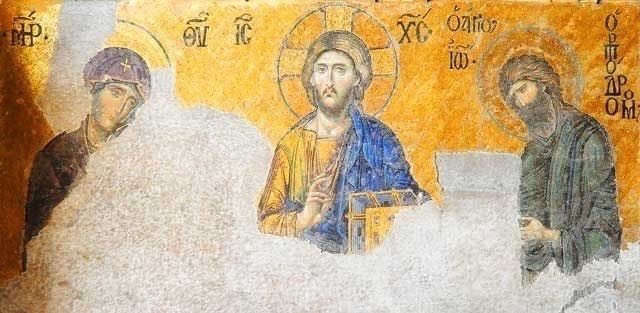

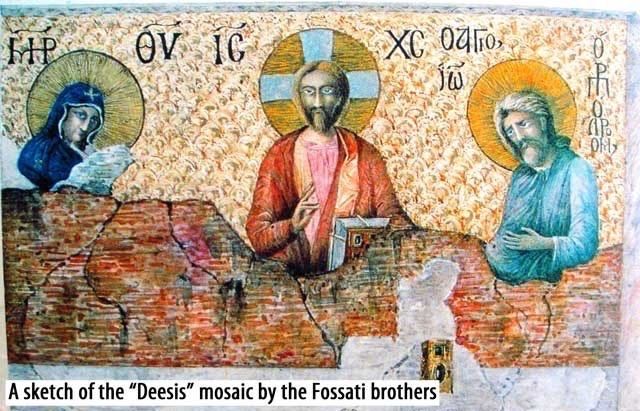

The first mosaic you come across is the “Deesis” (No. 13), which is a type of mosaic easily noticeable in many churches, depicting Christ, the Virgin, and St. John the Baptist. This one dates from the early 14th century. Christ is pictured in the middle with the Virgin and St. John the Baptist at his side asking Christ on behalf of humanity to pardon humanity’s sins.

Some say that this is perhaps the finest Byzantine mosaic which can be seen anywhere in the world. There is the gentle scalloped gold background, upon which the incredibly realistic figures reside, looking more like paintings than mosaics. The tiny colored blocks used in a mosaic are much smaller than usual, and therefore, a more gradual gradation is achieved, especially upon the faces.

You may also notice that the gold tiles of Christ’s halo are patterned in swirls, a subtle yet effective differentiation from the background tiles.

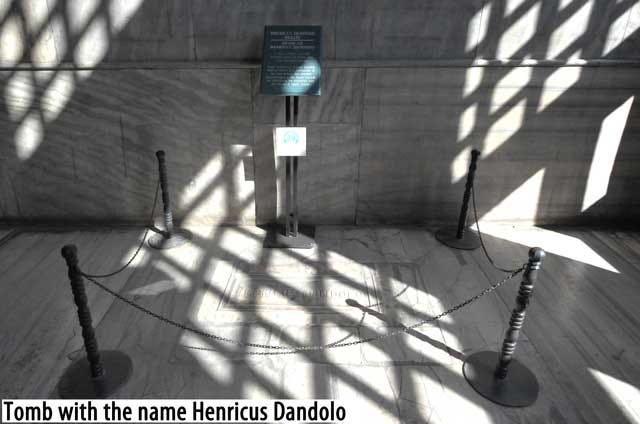

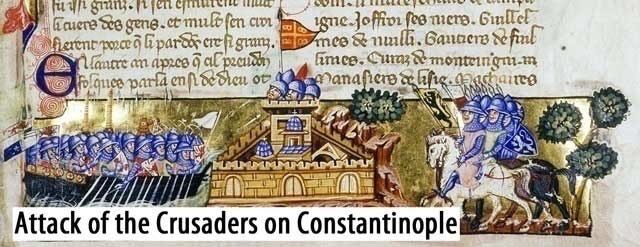

Close to the “Deesis” is a tomb with the name Henricus Dandolo carved upon it. This was the man who was one of the leaders of the disastrous Fourth Crusade in 1204 that besieged and took Constantinople in an unprecedented breach of Christian unity. Neither Constantinople nor the unity of the churches were ever the same again.

Dandolo died in 1205, very soon after the conquest of Constantinople, and was indeed buried in the Hagia Sophia. However, this tomb you see is not the original and is most likely a 19th century addition. Where his real tomb once was and what happened to it is a mystery.

You will next come to two mosaics very close to one another (No. 14).

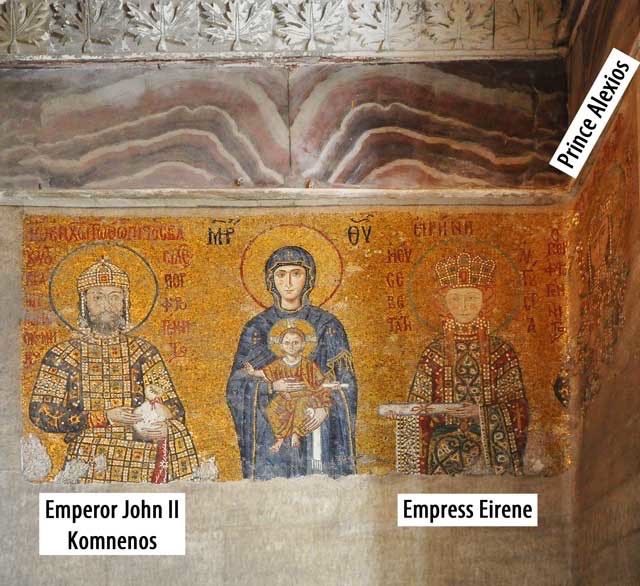

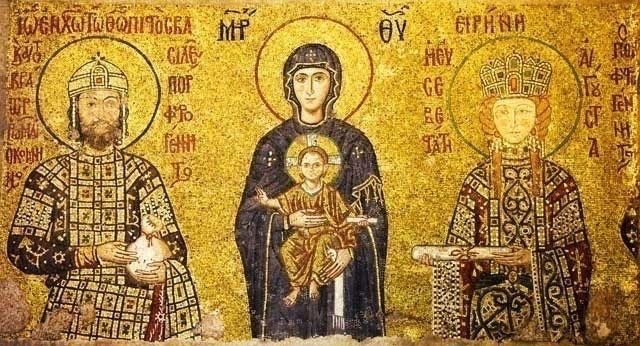

The first mosaic dates from the 12th century and depicts the Virgin flanked by Emperor John II Komnenos and his wife, Empress Eirene.

John II was a well-loved emperor, so much so that he earned the epitaph “John the Good.” Eirene, the striking figure with red hair, was also much loved and eventually came to be honored as a saint by the Orthodox Church.

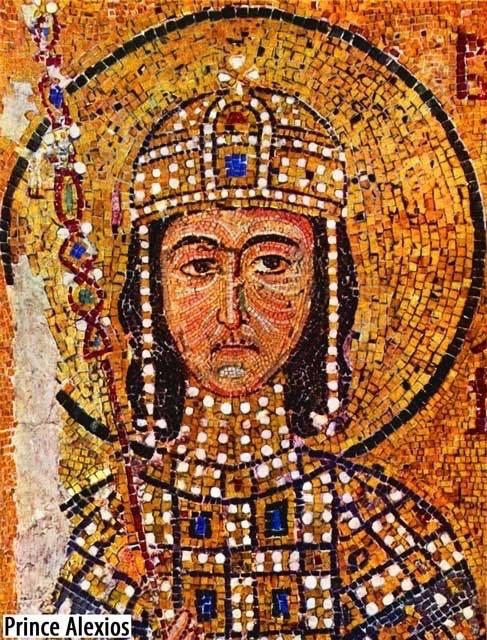

On a separate piece of wall to the right is their eldest son, Prince Alexios.

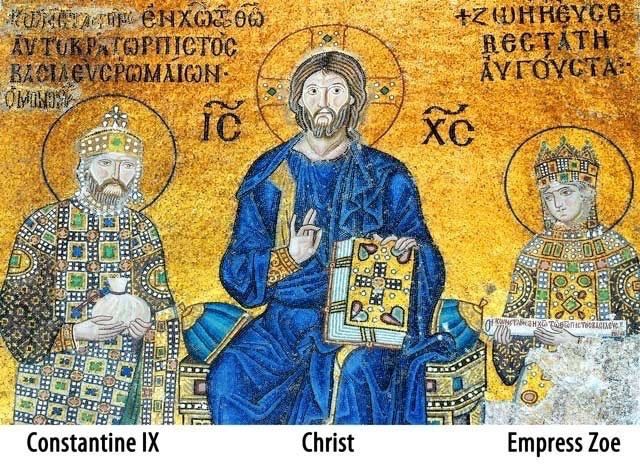

On your left side you see another mosaic with three figures, who are, from left to right, Constantine IX Monomachos, Christ, and Constantine’s wife, Empress Zoe. Constantine is depicted offering a bag of money to Christ, and Zoe offers a scroll.

Empress Zoe is quite an intriguing figure in Byzantine history, and this mosaic is also unique in that there is evidence that the heads of the three figures and the inscription were at one point removed and then redone. No one knows the truth, but historians speculate that this may be due to the public’s changing feelings toward Empress Zoe.

Zoe was a powerful woman in her own right and wielded much power in her time. Reportedly, she remained a virgin until she was married at the age of fifty in the hopes that she would have a child as all of the male heirs to the throne had died. She never did bear a child, but instead she proceeded to have a string of love affairs and a total of three husbands. It is speculated that when she was removed from power at one point, the people attacked her mosaic in the Hagia Sophia, and then when she returned at a later date, she had the mosaic repaired – save that the face of her husband was updated to reflect her most recent marriage!

You have now reached the end of this side of the second floor, and must backtrack to go to the other side, where you will see the last mosaic.

While walking you can enjoy the splendid view of the Hagia Sophia below.

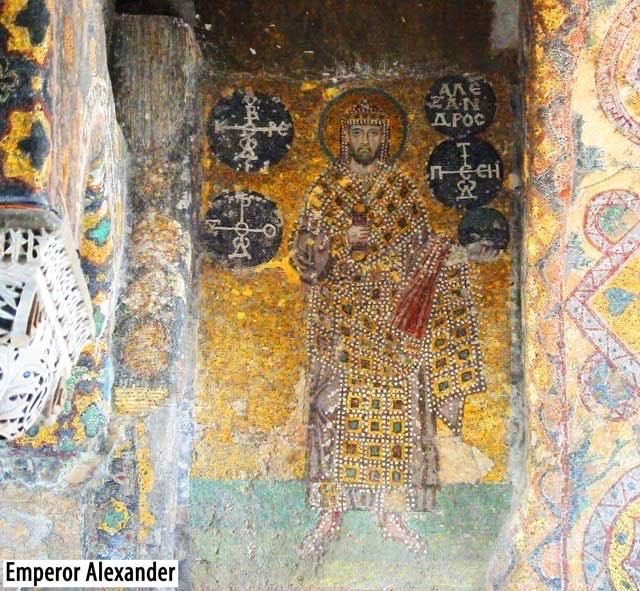

In the middle of the other side, you can see, in the area where the arches meet the wall, a well-hidden mosaic of Emperor Alexander, who reigned in 912-13 (No. 15).

Even Thomas Whittemore had much difficulty in finding it because the Fossati brothers had recorded it as being in the wrong gallery. Alexander was not a much-liked ruler and ruled for only thirteen months. Perhaps this explains the strange placement of his mosaic.

You can now proceed back down to the ground floor (No. 16).

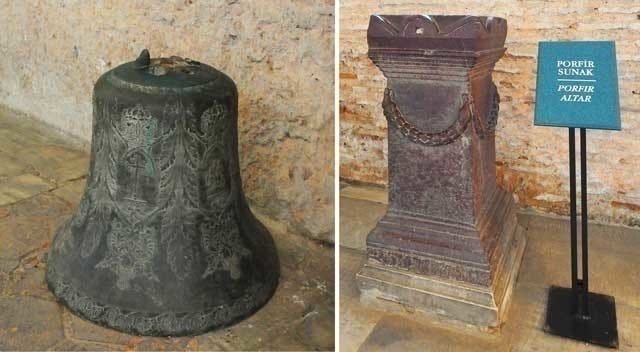

Here, in the outer narthex area (No. 17), you can see a number of interesting artifacts from the Hagia Sophia, including a porphyry altar and a bell that probably once hung in the bell tower.

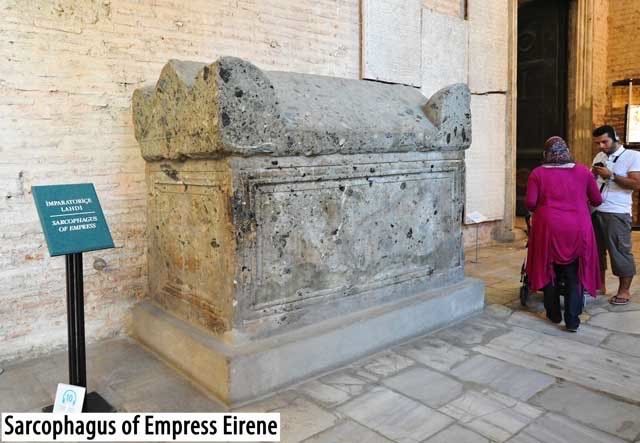

Farther away is a sarcophagus taken from the Church of the Pantocrator (now part of the Zeyrek Mosque) which once contained the remains of Empress Eirene, whose figure you saw before in one of the gallery mosaics.

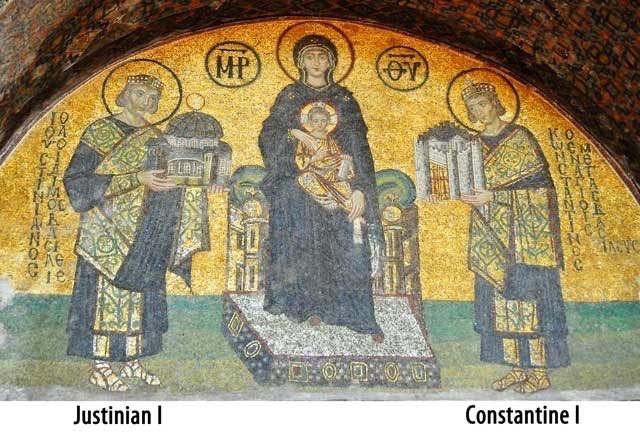

As you walk to the exit (No. 18), the last mosaic of the Hagia Sophia can be seen above the door, revealed to you in a mirror that has been placed so that exiting visitors do not miss it. It is mostly likely from the second half of the 10th century.

Here you see four people in total: the two in the middle, sitting upon a throne, are easily recognizable as the Virgin with the small Christ child on her lap. Approaching her from the right and the left are two Byzantine emperors. The left being Justinian I, the creator of the Hagia Sophia, holding a small model of the Hagia Sophia in his hands. And the right being Constantine I, the founder of Constantinople, who holds out the city of Constantinople.

The exit door, called the Splendid Gate, is also remarkable, as it was brought from a temple in Tarsus (in central Turkey) by Emperor Theophilos sometime in the 9th century. However, the door itself is reportedly from the 2nd century B.C.E.

The Baptistery, an original structure from before Justinian I’s time, has also been made into a tomb, and is just around the corner.

Now look once more over this monumental structure. Upon conquering Constantinople, Ottoman architecture changed significantly, and this was mostly due to the incomparable Hagia Sophia. The Ottomans realized the uniqueness of the structure, and incorporated many aspects of it in their own houses of worship. In this way, echoes of the vast dome and perfect harmony of the Hagia Sophia can be found all over Istanbul.

Moreover, two different cultures and styles live on inside the Hagia Sophia, which has been important to so many for so long. Emperors and sultans walked through its doors, priests and imams have preached upon its pulpits, and countless others have prayed similar prayers inside its walls. The Hagia Sophia turned none away.

Perhaps you can also see a kind of harmony between these two cultures even in the structure’s designs, or at least, you can search for it. While some complain that the Ottoman elements or the Fossati restorations get in the way of appreciating the Hagia Sophia’s original structure, the building, as seen today, reflects the whole of its long and rich history, all of which is important and deserves respect and preservation.

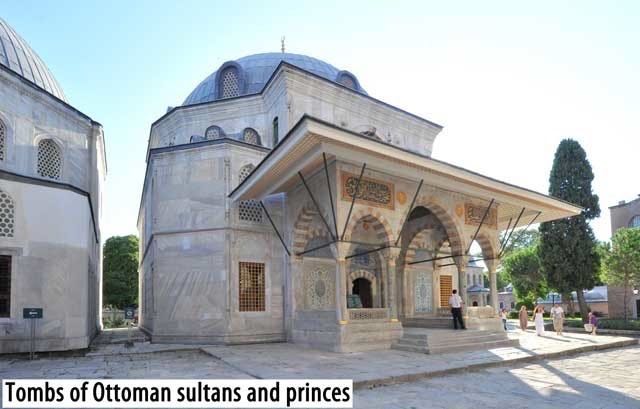

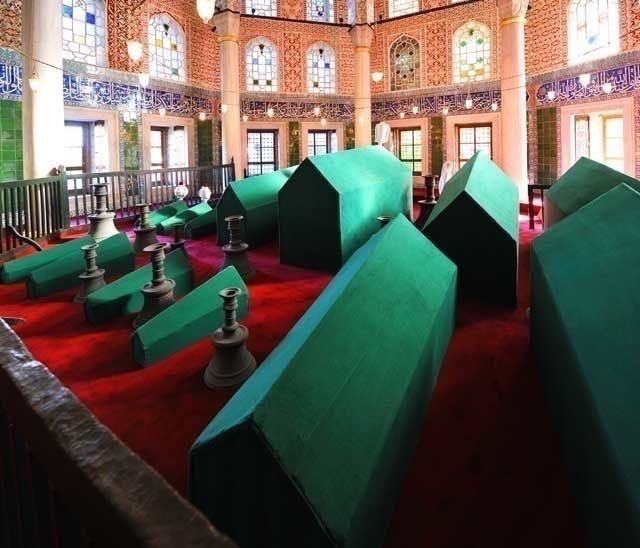

Around the rest of the area of the museum you can find the tombs or türbe of five Ottoman sultans and a number of princes.

There is also a lovely ablution fountain or şadırvan, with wide eaves and beautiful Ottoman calligraphy.

Water from the ablution fountain was used in ritual washing before prayer.

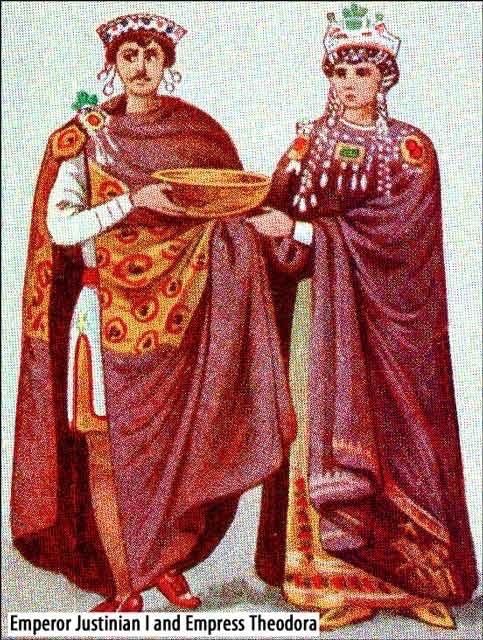

Emperor Justinian I was the mastermind who conceived the Hagia Sophia’s grand design.

Justinian I’s reign marks the Golden Age of the Byzantine Empire. He ruled from 527 to 565, an astonishingly long time, and during his reign his empire flourished. One reason for this was that he managed to re-conquer parts of the old Roman Empire, which had been taken over by the Ostrogoths, Vandals, Franks, and Visigoths, thereby restoring in part the glory of the Roman Empire.

The Roman Empire had previously split in 395 into the Eastern and Western Roman Empire, and that of the West fell in 476 when the last emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was forced from power. The Eastern Roman Empire to which Justinian I came to rule covered the area of what is now Greece, Macedonia, Bulgaria, Albania, and Serbia, and then also the lands north up to the Danube River. Its eastern boundaries covered Anatolia in modern-day Turkey, and went south down into Jordan, and then crossed some way into Egypt and part of Libya.

This Eastern Roman Empire, especially compared to the Western Roman Empire, was fairly secure and prospered for a long period of time. Despite the difficulties that Justinian experienced at the end of his reign, the empire did not actually begin its decline until well after Justinian’s time.

Justinian I came to power essentially through Emperor Justin I, his uncle. Justin I was somewhat of an unusual emperor, for he was essentially uneducated, not used to governance, and quite old at the time. Justinian came to Constantinople with several others of Justin I’s family members to receive the kind of education the emperor himself had never received. Soon after arriving, Justinian’s ambitions and intelligence were noticed by Justin I, and the older man sought the younger’s advice more and more often. Then, when Justinian was well into his 40s, the elder man died, and Justinian became sole ruler of the Byzantine Empire.

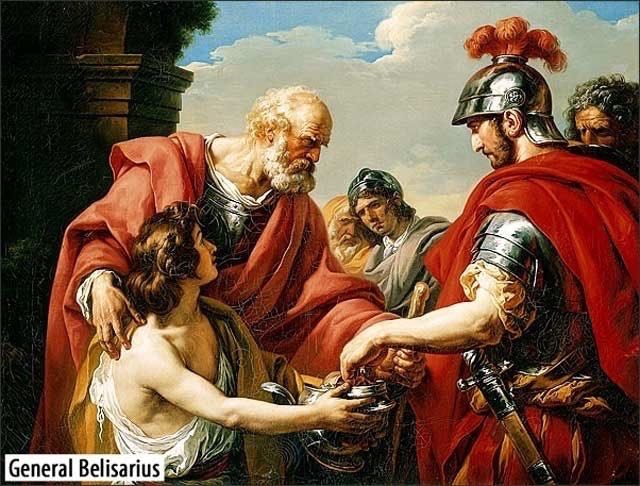

A war with Persia consumed the first five years of Justinian I’s reign, and although the ending note was on a treaty of perpetual peace, this was hardly possible in the long run. The first war with the Persian Sassanids came about in 526, instigated when they invaded what is modern-day Georgia. The Byzantine army under General Belisarius met with that of the Persians in Dara, where, although outnumbered, the Byzantines secured a victory.

However, it was not to last, for soon after the forces met again in 531 at Callinicum near the River Euphrates, where Belisarius was the loser. Then, the Sassanids were willing to negotiate peace, if only to extract a large sum of money from the Byzantines – 5,000 kilograms (11,000 pounds) of gold, to be more precise.

The first serious test of Justinian I’s reign, and perhaps the most dangerous, came in the form of the Nika Revolt in 532. This revolt came about primarily due to the unpopularity of Justinian I and his empress, Theodora. The old ruling class felt that Justinian I and Theodora, since they came from a lower social class, did not deserve their respect. Therefore, when Justinian I and Theodora began to demand elaborate ceremonies in their honor the old ruling class resented being forced into such ritualized submission.

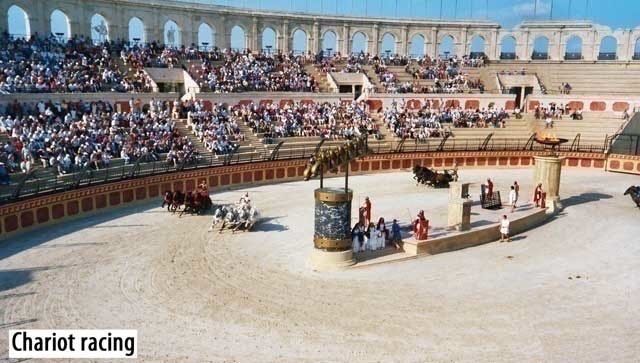

There was also bitterness among some of the lower classes due to such things as tax collection. But the riots first became manifest in the form of a conflict between the Blues and the Greens, who were the supporters of two factions of charioteers who would race around the hippodrome.

All in all, there were four factions: the Blues, Greens, Reds, and Whites, but the latter two had largely fallen from favor, leaving the majority of the masses as fans of the former two.

The importance of chariot racing in society of that time is difficult to overstate. It was the main form of social entertainment for the vast majority of the population, and everyone had a favorite team, and knew those of the others. Justinian I and Theodora considered themselves Blues and would even at times show other Blues special favor.

The Blues and Greens often operated like gangs, and violence had been on the rise during the beginning of Justinian I’s reign. In the events leading up to the riots, seven Greens and one Blue were detained on murder charges and were to be executed. Somehow, for two of those criminals, the hangman’s rope broke twice, and they were finally taken to the church of Saint Lawrence where they were detained. On January 13, 532, at the chariot races, the crowds pleaded with Justinian to spare their lives. When the crowds saw that Justinian was not moved, the Blues and Greens joined in communal anger, and the riots began. It’s possible also that several unhappy senators may have had a hand in provoking the crowd to violence.

The rioters burned down several official buildings and demanded the replacement of a few key officials of the empire. The rioters soon were being led by notable politicians who felt enmity toward Justinian I, and it became evident that the riot had turned into a revolt. It was only lucky that Justinian I’s generals Belisarius and Moundos, trusted officers, were around. Their troops ambushed the rioters in the Hippodrome one night, killing an incredible 30,000 of them. This was the undeniable end to the Nika Revolt, and with his power secure, and peace with the Persian Sassanid Empire established, Justinian I could look to reconquering the old Western Roman Empire.

The re-conquest of northern Africa from the Vandals began in the 530s, and the Byzantines succeeded in taking it back in 533-34. After this, Justinian I’s attention turned toward the Ostrogoths in Italy, which then came back under Byzantine rule during the years between 535 and 553.

The re-conquest of both of these lands proved to be costly and time consuming. In northern Africa, the Berbers were difficult to pacify, and the re-conquest of Italy was secured amidst renewed hostilities with Persia.

Despite these problems, Justinian I even managed to expand the empire’s lands by taking the southern tip of Spain, which was added to the empire in 550. Although these conquests were impressive, they also significantly overstretched the means of the Byzantines, and the strain began to show already in the 540s. Byzantium had grown to see its largest extensions realized but would not keep them for very long.

One huge strain on the empire occurred when bubonic plague struck in the 540s. Countless people died during the plague years, perhaps up to a third of the population. It is even said that Justinian I nearly fell to the disease. Needless to say, this had a profound effect on the Byzantine’s prosperity and decreased the well-being of its citizens long after the threat of the plague faded.

But plague was only one of Justinian I’s problems after the halfway point of his rule. Perhaps the problem that most consumed Justinian I’s reign was that of church unity. The Council of Chalcedon, which is modern-day Kadıköy, a district of Istanbul, in 451 had been arranged to settle the question of Christ’s nature, and the council ended up ruling against the Monophysites, or those who believed that Christ had a single nature, which was wholly divine. Instead, the council was in favor of the theory of the Chalcedonians who believed that Christ had two natures, both divine and human, and that neither superseded the other.

Unfortunately for the Byzantine Empire, the ruling of the council had little effect on people’s beliefs in the East where places such as Egypt and Syria were still very much Monophysite. In the years that followed, rulers of Constantinople would sometimes turn to persecution to try and force the Monophysite side to give up their belief.

Although they also practiced other forms of persuasion, and even attempted reconciliation, the two sides could not be reconciled in Justinian I’s time. Indeed, the division between the Chalcedonians and Monophysites went so far as to go all the way up to Justinian I and his empress, Theodora, who harbored Monophysite sympathies.

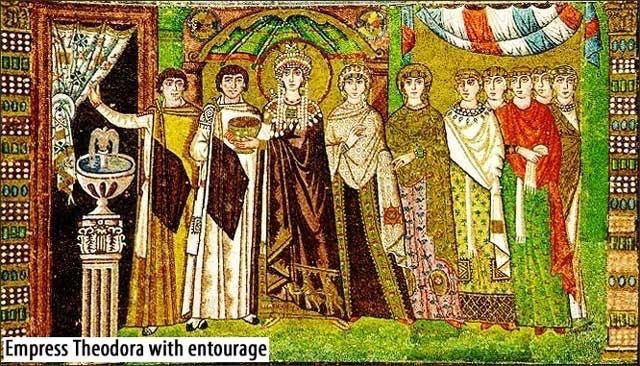

Theodora, of course, also deserves some exposition. Hers was a romantic life: born into poverty along with two sisters to a widowed mother, the siblings eventually turned to the stage to try and make a living. No one could have believed that an empress could arise from such humble beginnings. Indeed, there were laws prohibiting royalty from marrying actresses. The term actress in the Byzantine’s times had a different meaning from our own, for if one were an actress, it was very similar to being a courtesan. Women who were actresses occupied one of the lowest rungs of society and had little to no power or money in the world. Even if one developed some kind of following as an actress, there was limited mobility for her.

A few rulers tried to close down or regulate theaters, but since going to the theater was one of the favorite pastimes of the Byzantines they could not be wholly banned. During her time as an actress, Theodora eventually made her way to Alexandria in Egypt, which, at the time, was a stronghold of Monophysite belief. Most likely it is here that she became sympathetic to their belief.

It is not clear how Theodora and Justinian met. What is known, however, is that they met and were married before Justinian came to the throne, and that even though the law against marriage to an actress had been abolished, it still created something of a controversy. But Theodora soon proved her strength of character and was thoroughly engaged in politics and state affairs, nearly to an equal extent as Justinian I himself. It is even said that it was she who convinced Justinian I to stay and fight the rebels during the Nika riot. While the men spoke of fleeing, Theodora gave an impassioned speech and convinced them to stay.

During their reign, Justinian I instituted many different ceremonial practices, one of which included having the new governmental officials bow both at his feet and at Theodora’s. Not everyone accepted these new traditions with equal enthusiasm. Theodora also worked at improving the reception of actresses and sought to put an end to forced prostitution. She is known today as being one of the strongest women in Byzantine history.

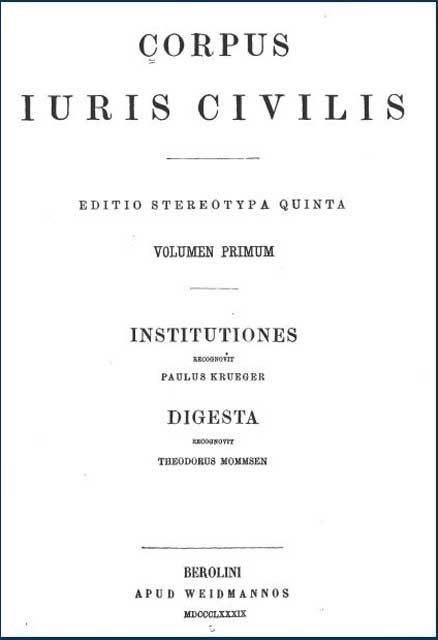

Besides his famous, brazen wife, his re-conquest and expansion of Byzantine territory, and the magnificent buildings with which he adorned Constantinople, Justinian I is further remembered for his complete renovation of Byzantine-Roman law. Before Justinian I, Roman law was in an incredibly disorganized state; there were too many laws so that many of them were not even remembered anymore. A unique aspect of Roman law was that each and every law that was made in the Roman Empire since its inception was supposed to still hold weight. Even long forgotten, small rulings that had occurred hundreds of years ago could be brought up during a given case and have an effect upon its outcome. By codifying the ancient Roman laws, Justinian I was not only simplifying things for lawyers, but more importantly, he was making it so that normal people could also hope to understand it.

Justinian I began to reform Roman law almost immediately upon his ascension to the throne, and he worked on the project nearly all through his reign. In 553, the first part of the major work was done, and a series of fifty volumes came into being called “Digest.” However, this soon proved not enough for Justinian I, who then issued a new codex called “Codex Justinianus,” which contains twelve books in total. Any laws not present in these books were no longer valid.

Justinian I not only reformed and codified the old laws, but he also wrote many new laws, seeking to further perfect and equalize, at least in some ways, the justice system of his empire. Justinian I wrote new laws or reformed old laws to improve the rights of Jews, women, and also slaves in society, to the extent that his time’s rigid social structures would allow. However, he was not so kind to pagans and Samaritans in his laws.

The whole of his laws are called “Corpus Iuris Civilis,” and has been translated into many different languages. It has influenced law-making all over the world, and its effects are still visible today. Together they are an enormously important source of Roman law as Justinian I had documents surveyed all the way back to the 1st century B.C.E.

In every domain of Byzantine life, Justinian I’s goal was to re-establish the glory of the empire. His buildings, therefore, were also fantastic, and the preeminent example is, of course, the Hagia Sophia, his architectural adornment of Constantinople, for which he is remembered until today.

But now let us move on to the Ottoman era.

The Hagia Sophia has been an important monument for both Muslims and Christians. Mehmed II, the conqueror of Constantinople, walked into the city triumphantly on Tuesday, May 29, 1453, through the Edirne Gate and went directly to see the Great Church. Before entering, Mehmed II humbled himself before the great structure and poured a handful of dirt upon his turban. Surely he knew the greatness of the city he had conquered.

Since the Hagia Sophia was such a splendid building, and since Constantinople had been a successful city for so many years, Mehmed II must have felt like this good karma would also spill over into his own vision of remaking Constantinople into the capital of a new empire.

Of course, some changes to the structure of the Hagia Sophia were made in order to change its religious affiliation. The mosaics were plastered over and painted with Ottoman-style calligraphy and geometric designs, the bell tower torn down and replaced by minarets, and much of the liturgical finery was removed in preference of a less-ornate, quieter setting. Prayer rugs also lined the floor, and oil lamps were hung from the ceiling. But the structure remained just as popular as in Byzantine times until its secularization in 1931.

Sultan Abdülmecid I, who reigned 1839 to 1861, was sultan during one of the most important renovations of the Hagia Sophia. He was a cultured man and helped to begin the period of reorganization, known in Turkish as Tanzimat. Although his reign was particularly troubled, he was still able to pay attention to the Hagia Sophia, which was in desperate need of renovation. He asked the Fossati brothers to come and restore the Hagia Sophia in 1847.

It had been much too long since the last restoration, and the monument’s structural integrity was beginning to suffer. As the brothers were working, it is said that they discovered some gold tiles one day and uncovered enough of the plaster to reveal part of the mosaic underneath. It seems that after the Hagia Sophia’s mosaics had been covered up they were eventually forgotten, although it is true that the angels in the main dome’s pendentives were never fully obscured.

The sultan came to see their discovery and decided that the brothers should look for more mosaics and allowed them to make drawings of them, as well. Given that the Hagia Sophia was a mosque at the time, known as the Aya Sofya Camii, the figurative mosaics were covered in plaster again after they had been exhumed and copied onto paper.

Unfortunately, the Fossati’s drawings were never published in their lifetime, and it was only in the 20th century that the mosaics of the Hagia Sophia came to be known from them.

In any case, the Fossati’s main objectives were to recreate the Ottoman-style decoration of the mosque, both inside and outside, and to stabilize the structure, both of which they accomplished. One can still see many elements of the Fossatis’ renovation; in fact, most of the painted areas are the work of the Fossati brothers.

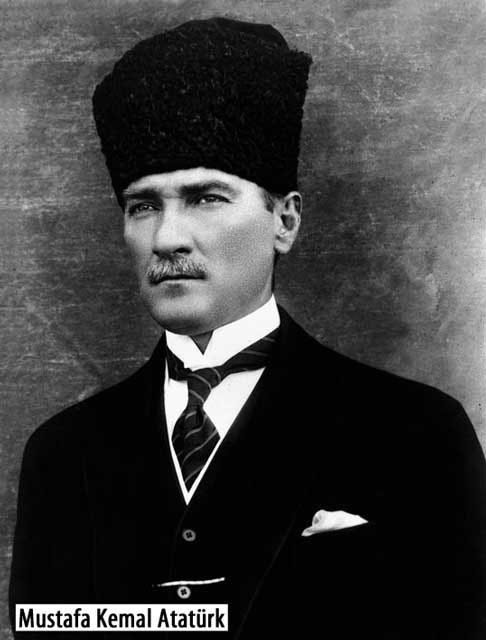

The Byzantine Institute of America, under the guidance of Thomas Whittemore, came to work on the Hagia Sophia in 1931 after it had been secularized and turned into a museum. In part, Whittemore helped to accomplish this by meeting with Turkey’s new president, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, and convincing him of the importance of secularizing and restoring the Hagia Sophia.

Atatürk, a great secularizer and modernizer, agreed that this was in the best interest of both Turkey and the building itself, and gave the Byzantine Institute the job of restoring the Hagia Sophia, the Chora Church, and a few other monuments in Istanbul.

Those in charge of the restoration efforts had an enormous job, for they had more than one artistic style to preserve. For one, they often had to try to both reveal the Byzantine mosaics and also partially preserve the Fossati brother’s painted Ottoman and Gothic designs. The institute worked for 18 years, and they are largely to thank for the good state of the Hagia Sophia today.

Since 1985 the Hagia Sophia is included as part of the Historic Areas of Istanbul in the World Heritage List of UNESCO.

More recently, in preparation for 2010, the year that Istanbul became a European Capital of Culture, another substantial cleaning and restoration effort was made, in which mosaics never before seen by the public became visible.

This concludes our tour of the Hagia Sophia, the epitome of Byzantine architecture that forever changed the history of architecture.

No.s 11-16 are up in the Galleries

14. Two Mosaics (The Virgin, Emperor John II Komnenos, Empress Eirene; Constantine IX Monomachos, Christ, Empress Zoe)

15. Mosaic of Emperor Alexander

Turkish Cuisine – Turkish food present and past

What do you think of when you think about Turkey? Perhaps you will think of Cappadocia, that ancient city with its strange fairy chimneys and underground churches, or the Hagia Sophia, the centuries-old Byzantine masterpiece in Istanbul. Other people may think of the beautiful Aegean Sea, with its hot sun and white sandy beaches. But one thing that may surprise people unfamiliar with Turkish culture is that almost above all these other things, visitors to Turkey will remember, and miss afterward, Turkish cuisine, or Türk mutfağı.

This comes as no surprise to most Turks, many of whom will proudly tell you that Turkish food is the best in the world. You’ll have to try it for yourself and see if you agree.

Let’s first look at typical Turkish meals and give a few examples of kinds of foods to try in Turkey. Then, later, we will discuss the origins of Turkish cuisine and how it differs during the month of fasting – Ramadan. Finally, we will list some recipes in case you want to try your hand at making some Turkish food yourself.

It is of course too difficult to list all the different Turkish dishes, as Turkish cuisine is a mixture of various influences such as Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, Balkan, and historically Roman and Byzantine. However, a short list of general kinds of food can be given.

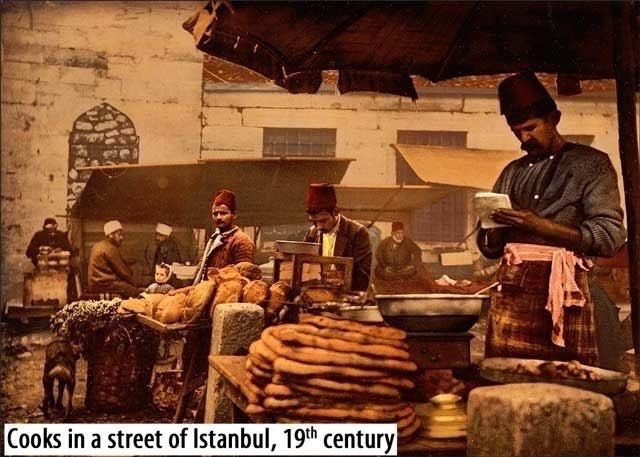

To the Turkish people, breakfast is very important; there are even special restaurants that specialize in serving only breakfast. The simplest Turkish breakfast will include cheese, olives, slices of tomato and cucumber flavored only with good olive oil and lemon, and the ever-present simit.

Simit is everywhere in Turkey and is definitely one of the most loved Turkish foods. They are shaped like a large, thin donut, and are covered in sesame seeds.

They may seem like nothing special to most tourists, but fresh simit goes perfectly with a Turkish breakfast. Hardly anyone bakes their own simit, and will simply buy what they need from the simit sellers who make their rounds in the morning.

More elaborate Turkish breakfasts will involve all of this, plus egg dishes such as menemen: scrambled eggs with tomatoes and pepper; also jams; a savory pastry börek; clotted cream kaymak; honey; and many other things. Sweet breakfasts, like pancakes or sweet cereals, are very rarely eaten, and would seem very strange to a normal Turkish person.

Lunch and dinner are similar to one another, with perhaps dinner being slightly larger. First, Turks normally eat soup, called çorba in Turkish.

For both lunch and dinner, it is typical to begin with a small bowl of mercimek, a lentil soup made of red lentils, but the color of the soup is usually yellow or green, tavuk suyu, a chicken soup, or maybe yayla, a yogurt with rice and mint. There is also tarhana, a very interesting and healthy soup. It is harder to find, however, because it takes a long time to prepare the main ingredient of the soup. Tarhana is made from yogurt and vegetables, which are dried in the sun, then ground into a powder. This is then added to hot water or chicken stock to make a very delicious and traditional soup. Its taste is also very unique – try it if you can find it. Turkish soups tend to be quite plain and emphasize their main ingredient; the only other added flavors are perhaps a bit of tomato or pepper paste, some spicy pepper, mint, oregano, or lemon. But they are far from boring and do a good job as appetizers.

The Turks are serious about their meat, and it may be difficult for vegetarian tourists to convince waiters that they absolutely do not eat any! There have been many stories of vegetarians being served a dish with a small amount of ground beef in it, only to be told by the waiter that this meat doesn’t really count as meat; it is too small.

If you are a very strict vegetarian, you may want to stick to the zeytinyağlı dishes; even the soups will almost always be made with beef or chicken stock. If you absolutely don’t want anything with meat, just ask, “Etli mi?” which means, “Is it with meat?” An answer of “Hayır” means no and an answer of “Evet” means yes.

As for the meat dishes, the best place to eat kebab is at ocakbaşı – a grilled meat restaurant. Here you’ll find all kinds of kebabs (kebap in Turkish), ranging from the spicy Adana kebabı to the roughly cut pieces of lamb called çöp şiş. Usually these are served with a flat piece of bread called lavaş and raw onions with sumac, a lemony, purple spice sprinkled over them.

Of course, the döner kebap is everywhere and usually eaten as a fast food. However, at restaurants, sometimes you can find a special döner that is roasted over wood, which supposedly gives a better flavor to the meat. Another very delicious dish using döner meat is the İskender kebabı. This dish was first created in Bursa, and purists will say that you should not eat it anywhere else but there. However, one can get perfectly good – even delicious – İskender kebabı in Istanbul as well.

First, on a metal plate, small pieces of the flat pide bread are put down. On top of this come thin slices of döner meat which is almost always lamb, and then grilled tomato and pepper. The crowning glory of the dish, however, is the rich tomato and butter sauce that is then poured over everything. A side of yogurt finishes the dish and helps to lighten things – if that’s possible.

An entirely separate category of meat dishes in Turkey are Turkish meatballs, called köfte. These are not usually round, but flat, and are most often eaten grilled – in this form, they are called ızgara köfte. You may also like to try ekşili köfte, which is a sour meatball stew.

Meatballs also come as appetizers in Turkey, like the içli köfte, which are American football-shaped meatballs with walnuts inside, covered in a thin corn flour mixture, and then fried. Then there is the çiğ köfte, which is traditionally made with raw beef (çiğ means raw); the Turks say that after it has been worked on for hours by the chef, the meat is cooked. Many people express doubts about eating raw meat, but it is still quite a popular appetizer. However, most of the small çiğ köfte sellers only make the vegetarian version. The meat-free version is very tasty, and in fact many Turks nowadays prefer them to the more traditional meaty variety. The latter can be really spicy, as well.

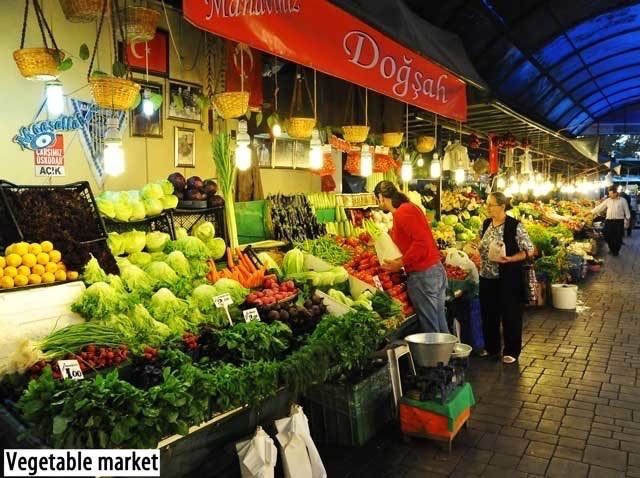

If you are at a place that serves home-style cooking (ev yemekleri) you should certainly try one of their cold vegetable dishes prepared with olive oil – zeytinyağlı.

Usually these dishes are seasonal, so in spring you will find artichokes (enginar), green peas (bezelye), and broad beans (bakla); in summer, squash (kabak) and okra (bamya) are popular; in autumn come Brussels sprouts (brüksel lahanası), leeks (pırasa), and celeriac (kereviz); and in winter there’s not much left but spinach (ıspanak), swiss chard (pazı), and other root vegetables. During all twelve months you can eat borlotti beans (barbunya) and fresh beans (taze fasulye). They are all quite delicious and healthy.

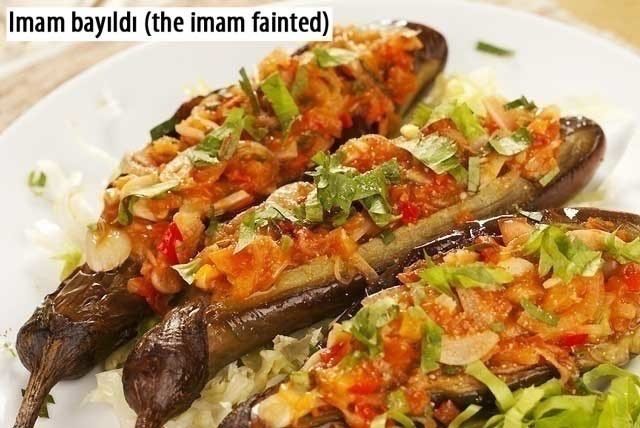

Also in the zeytinyağlı category are the yaprak sarma, stuffed grape leaves (dolma), biber dolması: stuffed peppers, and imam bayıldı, which translates to the imam fainted.

This dish is composed of fried eggplants stuffed with a mixture of tomato and onion and lots of garlic. The story goes that an imam, a Muslim prayer leader, fainted after learning how much olive oil was needed to make this dish (after tasting it and finding it to be so delicious)!

Hot dishes most often include meat, although never pork because of Islamic tradition. The dishes that can be found in many restaurants serving traditional Turkish and Ottoman food, include karnıyarık, which is a fried eggplant stuffed with ground meat and spices; güveç, which is a lamb and eggplant stew, named after the kind of clay pot it’s traditionally cooked in; and then kuru fasulye, which are dried beans cooked with tomato paste and meat.

All of these dishes will leave you satisfied, but at least once, while you are in Istanbul, you should try hünkar beğendi, which literally translates to her royal highness liked it. This dish is made by placing stewed pieces of lamb on top of a creamy puree of roast eggplant and cheese.

The story goes that one day Empress Eugenie, wife of Napoleon III, was dining with Sultan Abdülaziz and was served this dish. She liked it so much that she requested the recipe for her own cook. The sultan granted permission for the recipe to be shared, but unfortunately the French chef never learned how to make the dish. Apparently, when the French chef brought all his measuring equipment and cooking tools to the Ottoman kitchen to learn how to make the dish, the Ottoman chef refused to use them and even threw them away. There was no way that the two could work together, and so the French visitors returned home without the recipe for the delicious lamb and eggplant dish.

With Istanbul so close to both the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea, eating a nice fish dinner is highly recommended.

The season for fish is winter, but this does not mean that you cannot enjoy a fish dinner during the other months; just that fish are simply a little more delicious and available in greater variety during winter.

A traditional fish restaurant will cook fish, regardless of the kind, in one of three ways: they will stew it (buğlama), grill it (ızgara), or fry it in a batter of wheat or corn flour (tava).

Before the fish entrée, a number of appetizers (meze) are enjoyed. These include patlıcan salatası: a grilled eggplant dish, beyaz peynir: a white cheese like feta cheese, acılı ezme: spicy pepper paste, kalamar: calamari, and midye dolması: stuffed mussels.

It is normal to have a small dessert, especially after eating fish, because Turks believe sugar helps in the absorption of phosphorus found in fish; we cannot verify this information, but it is a good excuse to enjoy a dessert.

If you are not eating only fruit as dessert, then desserts in Turkey are generally quite rich and very sweet. Speaking of fruit, all produce is wonderful in Turkey, but if you are lucky enough to be here for fig season in late summer or early autumn, you’re in for a special treat, for Turkish figs (incir) are said to be the best in the world.

By now, everyone knows baklava, and indeed a number of different cultures claim this dessert as their own. Baklava is made from paper-thin sheets of pastry layered one on top of another with nuts in between. Usually, they are cut into diamond or square shapes, baked, and then saturated with sugary syrup.

Puddings are also quite popular: there is the muhallebi, which is a milk pudding often perfumed with rose or orange blossom water; sütlaç, which is a kind of rice pudding; keşkül, which is almond flavored; and the very unique tavuk göğsü, which is a thick, gelatinous pudding made with shredded chicken breast meat. It is claimed that the chicken is added only for the texture – indeed, the taste of chicken can hardly be detected.

Then there are the desserts which are soaked in syrup: Kemal pasha, named for Atatürk, are round balls which include a little soft cheese in the dough; tulumba are shaped like grooved cylinders and are fried; revani is normally diamond-shaped and made of semolina flour; and then there is şekerpare, which is made of semolina but includes almond.

Künefe is a dessert only for those with a serious sweet tooth and a strong stomach. It consists of fine strands of dried pasta fried in butter with melted cheese in the middle, all soaked in syrup.

Helva or halva is a wonderful confection usually made of sesame paste, and it is traditional to eat warm halva after a fish dinner. Halva is heated in the oven and it becomes a thick, sticky paste.

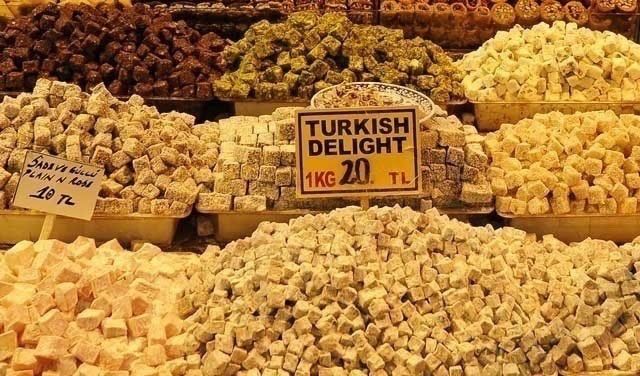

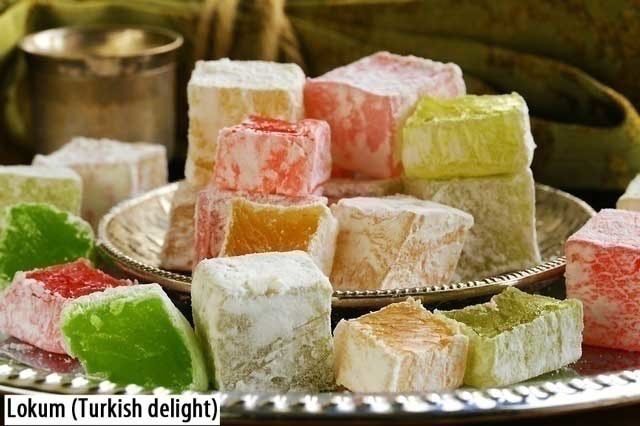

Lokum, known to the West as Turkish delight, is not considered dessert in Turkey, but rather a light snack, and is often eaten with a cup of strong Turkish coffee. If you are going to someone’s house for dinner, you may bring a box of lokum or another sweet with you.

Speaking of coffee, let’s now spend some time on Turkish drinks.

Turkish tea or çay is everywhere, and is drunk at every meal, and between meals. In fact, some Turks seem to constantly have a small glass of tea in their hands.

Turkish tea is much stronger than tea found in places like the U.S. or Europe due to the way it is brewed.

The Turks do not boil water and steep the tea for only a minute or so; they use two special teapots, the smaller of which sits on top of the larger, and steep the tea for a long time, using a very different technique. First, in the top, smaller pot, loose black tea is added, usually one very full teaspoon per person drinking tea. Then, in the bottom pot, water is boiled. The boiled water is then added into the tea in the top pot, and then the bottom pot is filled again with water. The pot with tea is placed on top of the pot with the water, and then the fire below is lit again. The water continues to lightly boil, and the steam from this pot continuously heats the tea in the pot above it.

After around 5-10 minutes, depending upon one’s preference, the little tulip-style glasses are brought out for serving the çay. First a little bit of the strong tea from the small pot is poured into the glass, and then the glass is filled with hot water from the bottom pot. Sugar is then added according to one’s preference. Turkish tea is normally served absolutely boiling hot – be careful! This kind of tea is both made at home and found in restaurants and cafes.

Apple tea is a very recent drink in Turkey, and it is popular with tourists. Most normal Turkish cafes away from tourist areas will not have apple tea at all.

Coffee, or, rather, Turkish coffee (Türk kahvesi), is also very important in Turkey. The Turks use a special small pot in which to make this coffee, called a cezve; these are made of copper or stainless steel, and are tall, with a long handle.

Turks drink coffee from very small cups, much like espresso cups, and the coffee used is very fine, almost like a powder.

Turkish coffee is made by using a Turkish coffee cup to measure out enough water per person to put in the cezve, and then a heaped teaspoon of coffee per person is added to this, plus the sugar, if it is desired.

Then the cezve is placed on a very low flame or in sand and heated until just before the boiling point. This heating can be done once or even up to three times, and then the coffee, with the foam on top, is poured into the cups. Turks will let the coffee grounds settle to the bottom of the cup, and then drink only the liquid; the thick paste with the grounds is left in the cup.

It is also common for Turks to use the leftover coffee grounds in their cups to tell one another’s fortune. The drinker will turn the cup upside-down over the saucer, and then wait for it to cool. Then the fortune teller will pick up the coffee cup and read the coffee drinker’s fortune by trying to find pictures formed in the way the coffee grounds have run down the sides of the cup. It is fun, and often done amongst friends. You might see Turks trying to read each other’s fortunes at many cafes around Turkey.

Turks drink coffee anytime, and Turkish coffee is by far more popular than other kinds of coffee, but imported coffee drinks like cappuccino are gaining in popularity.

Coffee came into the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century, by way of Yemen, and it soon became an incredibly popular beverage. However, from the start it was also looked at with suspicion by the Islamic judges (ulema), as it was clearly a substance which altered the state of mind of the individual who drank it. It was not clear, however, how Islamic law should regulate such a substance, since its effects were unlike those of alcohol or narcotics.

The first challenge to coffee came during the 16th century, when a fatwa (ruling) was issued by the ulema (religious judges) which made reference to how coffee beans were roasted until they were black, and then how the suspicious drink was passed from one person to the next. It is not known exactly why these things were considered so bad, but they were suspicious enough for ships carrying coffee to Istanbul from Yemen to have their loads of coffee dumped over the side, into the sea.

But, as you can see, this did not stop coffee from becoming a kind of national drink in Turkey.

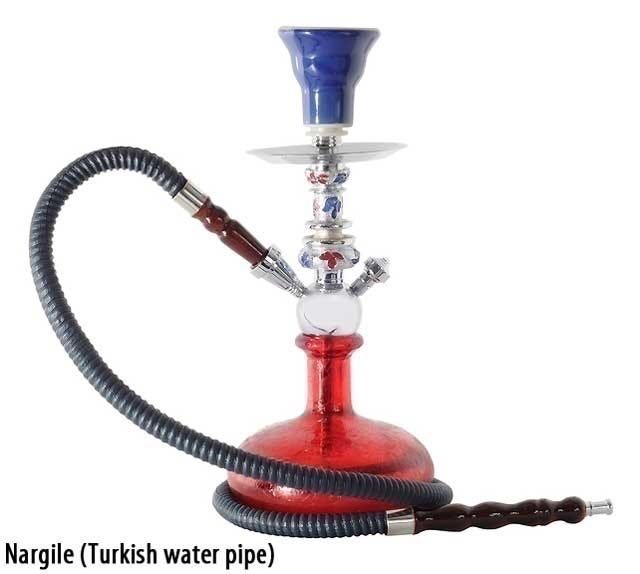

Tobacco came into the Ottoman Empire around the same time as coffee, and was also viewed with suspicion by the ulema. Finally Murad IV outlawed both coffeehouses and the use of tobacco in 1633, as they were seen as substances that led to sinful behavior. Indeed, coffeehouses had come to be associated with immoral behavior, as they were an easy place for people, which meant men, to meet.

But coffee and tobacco, which was smoked in coffeehouses using nargile (water pipe), proved to be too popular, and most people were reluctant to both enforce Murad IV’s law and also follow it.

No other sultan significantly challenged the consumption of coffee.

But back to drinks. Boza and salep (alternatively sahlep) are two beverages that are enjoyed during the autumn and winter months. Boza is a cold drink made of fermented grains, such as millet and wheat, while salep is a hot drink made from the dried and powdered root of a wild orchid mixed with milk. Both of these are rather sweet, and both are also served with a dusting of cinnamon on top. Unfortunately you will only be able to try these beverages in the cooler months; it is not usually the case that they are sold during the spring and summer.

Ayran, however, is a very traditional Turkish drink that can be found all year. It is a simple mixture of water, yogurt, and salt, and is very refreshing in the summer.

And then there is the strong alcoholic beverage called rakı. It is made from fermented grapes or raisins, with the addition of aniseed for taste. It is similar to ouzo and sambuca.

Rakı is a clear and strong drink itself. A little bit of rakı, not more than halfway up, is poured into a tall glass and water is added until the glass is full. The addition of water turns the drink white and cloudy. Another tall glass with only water is placed next to this. One sips the rakı, the white and cloudy drink, and chases it down with water.

Typically, rakı is drunk in tall, narrow glasses, while eating snacks such as beyaz peynir: white cheese, and melon. It is also often drunk with the starters before a fish dinner.

Interestingly enough, rakı is one of the national drinks of Turkey, a Muslim country, along with ayran. It must be said that being Muslim in Turkey is different from being Muslim in, say, Saudi Arabia. Turks are notoriously tolerant about alcohol. One can be a Muslim and still drink alcohol in Turkey – even every day. Rakı and beer are very popular. The Turkish interpretation of Islam is by-and-large quite liberal and open-minded.

Traditionally, there is no pork in Turkish dishes since the Ottoman times because of Islam. It’s a bit strange – most Turks will drink alcohol, but most Turks will still not eat pork. This is more because pigs are considered dirty and this image is quite unappetizing to most Turks.

Turkish food is not usually heavily spiced, except for some meat dishes like Adana kebab. Usually, the goal is to let the flavor of the main part of the dish come out, and spices are only used to enhance this flavor. Spices are not often used in vegetable dishes, but there may be a lot of spices in some of the meat dishes.

Of course, Turkish dishes differ from area to area. Turkey is a large country. Adana kebab from Adana in southern Turkey will be much spicier than Adana kebab in Istanbul. In fact, the entire cuisine of Adana is quite different from what you find in Istanbul.

Many of the spices sold in the Spice Bazaar don’t come from Turkey. During the Ottoman Empire, spices came through the Silk Road trade from China and central Asia. To be sure, Turks do use spices in their food, but of course not to the extent of people in India, for example. The Ottoman Empire controlled much of the spice trade, and so spices were important and profitable enough to warrant their own bazaar. Europeans especially came to buy spices from the Turks.

Around a Turkish table, the way the meal is started is by saying “afiyet olsun,” which literally translates to “may there be appetite” and is used in a similar way to the French bon appétit. This phrase is also used in response to a compliment to the food. If you tell the cook that the meal is delicious, saying, “Çok lezzetli,” they will reply, “Afiyet olsun.” If you are in a religious household, they may begin the meal with a short (or long) prayer. If you happen to drop some bread and a waiter picks it up, he may kiss it and touch it to his forehead three times, for in Islam it is a sin to waste food.

There are not so many manners to obey at a Turkish table. The Ottomans traditionally ate with their hands, but modern Turks eat with forks, spoons, and knives.

Turkey is still quite a traditional society, and so in many households, the women will do all the cooking – almost never the men. The women will also serve the men, with the eldest first, during the meal, sometimes men even leaving the table before the women can eat. However, this is changing, and it is more common now for men to share in the preparation of meals and everyone to start eating at the same time.

When Turks eat out at a restaurant, it is courteous to not begin eating until everyone has their food. One does not have to eat everything on one’s plate, but wasting food is usually considered to be a sin by most Muslims, and they hate to throw away food.

Mealtimes are important parts of the day for a family, but Turks rarely sit a long time at the meal table, the exception being Ramadan and other holidays. No special toasts are said. Şerefe is both the word for the balconies on a minaret and the word for cheers. Turks eat rather quickly – especially in Istanbul, which is a very busy city.

Now, let’s discuss the origins of Turkish cuisine. Since ancient times, Turkic tribes were largely nomadic, and their food reflected this. They lived in central Asia, which is still predominantly populated by Turkic peoples. They did not practice agriculture but had domesticated horses and other animals, some specifically for food such as sheep and goats. For this reason, they ate large amounts of meat and milk products, and especially enjoyed a drink called kımız (kumis), which was alcoholic and made from fermented horse’s milk. The horse especially was incredibly important to their way of life, and they became very skillful warriors on horseback. Interestingly enough, although horses were very valuable to the Turkic tribes during this period, horse meat was also consumed.

This way of life lasted for a long time until the tribes began the transition from their nomadic lifestyles. When this happened, they incorporated more of the products of agriculture into their cuisine and began to eat more bread and vegetables. Food such as kavurma: a kind of preserved lamb meat, pekmez: molasses, a thick syrup made from fruit, and ayran: a drink of yogurt and water, that are still very popular today, had already been developed in the 11th century. Indeed, yogurt is an invention of the Turkic peoples.

After the Turkic tribes entered Anatolia, which today is mostly the Asian part of Turkey, and the other surrounding areas, their foods changed again as they came into contact with the people already living in those areas. For example, a dessert you still can eat today in Turkey called tavuk göğsü: a baked pudding made from finely chopped chicken and milk, was adopted by the Turks from the Romans, and in fact, the Turks were the only civilization to have kept this kind of food.

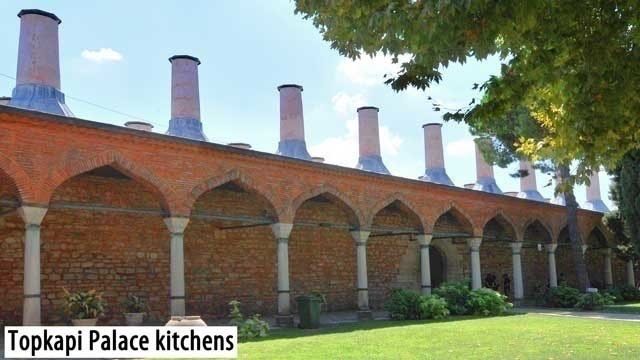

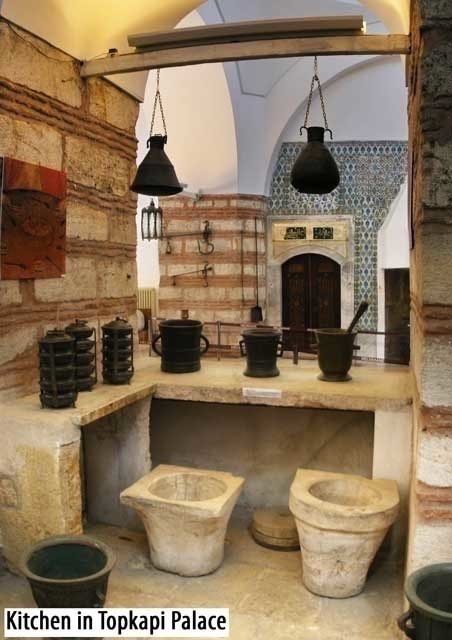

But the modern Turkish cuisine as we know it today was largely developed during the time period when the kitchens at Topkapi Palace were making food for the sultan, his large harem, and the whole royal court. The chefs in the palace were very secretive, however, over time some dishes and techniques became known to the public, and influenced the development of Turkish food very much.

During the time of the Ottoman Empire, Turkish cuisine became like a refined art form, and its vast array of styles of cooking, flavors, and ingredients is comparable to the other great cuisines of the world.

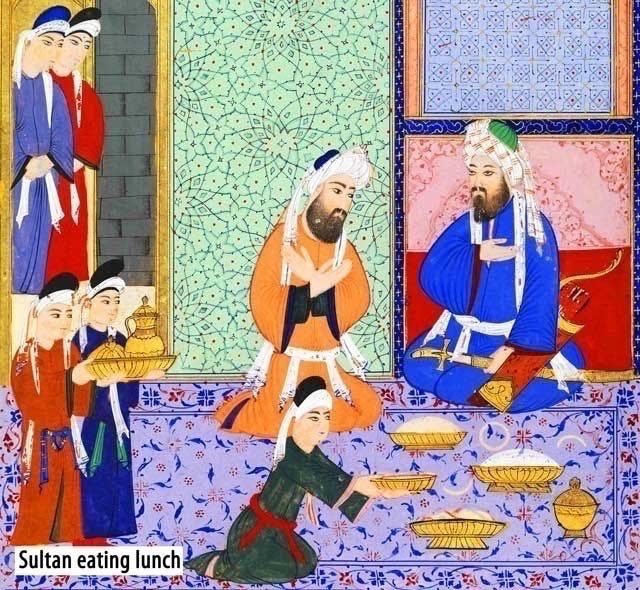

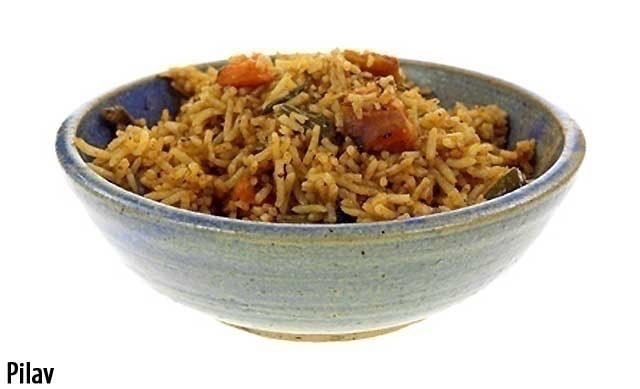

Usually, only two meals a day were eaten during Ottoman times, but the amount of people the Imperial Kitchen of Topkapi Palace fed was huge. Every day, around four thousand people were fed in the 16th century, however not everyone ate like the sultan. Most meals consisted of soup, rice, and a sweet dessert for the first meal, and the evening meal would sometimes have the addition of a meat dish.

In the 16th century, we know that around 30,000 birds and 22,500 sheep were cooked in one year. In the 16th century, there were around 5,000 people who were fed by the Imperial Kitchen; in the 17th century, there were already more than 10,000 housed, or at least working and eating at the palace.

The kitchens were strictly divided into sections, although the use of each section sometimes changed. It is known that there were sections specifically for making helva or halva, a sweet made from sesame paste; jam; şerbet: a sweet, fermented fruit drink; and pastry, to name but a few. The kitchens also produced soap, although, of course, not for food.

There was also a section called the kuşhane, which devoted itself to preparing new and delicious food only for the sultan and his special guests. The name kuşhane, literally bird house, comes from the kinds of bronze or copper dishes that the sultan’s meals were served in, which had a figure of a bird on top of the plate.

The hierarchy of the Topkapi kitchens was quite strict. All the people who worked in the kitchens were part of a guild, and like most guilds, this meant that they had to obey certain rules. Those who wished to become a cook had to first begin as an apprentice, obtain certain skills and serve as an apprentice for a certain amount of time before they could move up in the ranks. Before even making it to the kitchens at Topkapi, aspiring chefs would be sent to special schools set up in Bolu, some 200 kilometers (125 miles) from Istanbul, where they would receive their initial training. In the kitchens of Topkapi, in the 16th century, there were around 15 master chefs, 60 cooks, and then 200 other subordinates, all of whom had to answer to the head chef who oversaw the entire kitchen and all the food cooked there. At one point, there were 1,500 people working in the kitchens.

Most of these people under the head chef specialized in a certain area, like cooking poultry or sweets, or even in fixing the pots and pans. Very important was the helvahane, or sweets kitchen, where not only the sesame paste dessert of helva (halva), but also all the other sugary sweets the palace inhabitants enjoyed were made.

The sultan, who always ate alone, except on occasion of dining with guests, of course, enjoyed only the best food and service. However, in the early days of the Ottoman palace, the food was not overly fancy.

Mehmed II was known to be rather tight with money, and did not demand luxurious things often. His favorite foods are said to have been yumurtalı lapa: a kind of porridge with eggs, mantı: a kind of Turkish stuffed pasta, similar to ravioli, often with beef, and muhallebi: a milk pudding, still popular today.

A common dinner would have consisted of pumpkin soup, chicken kebab or another meat dish, a green salad with yogurt, a few preserved vegetables, and fruit.

There was a special servant for even the smallest of tasks, such as providing napkins. There was also a position for the person who tasted the sultan’s food; of course she or he was not only checking the taste, but also making sure the meal was not poisoned. This person also oversaw the organization of the sultan’s meals. Above all, the chefs who prepared the sultan’s meals prided themselves on the variety and the inventiveness of their meals. Because of these chefs’ desire to keep these special recipes a secret, many have been lost to us today – but thankfully, some became popular enough to have eventually entered modern Turkish cooking. We will name some examples later.

As the empire grew richer, so did the kitchens of Topkapi Palace. The best of the raw ingredients produced anywhere in the Ottoman Empire would first be reserved for the sultan; if any of it was left, only then could it be sold to the masses. From Thrace on the European side, came sheep and lamb; from the Balkans came cheese; from Egypt came sugar and grains; from Antep in southeast Turkey, pistachios; caviar from Russia and Iran; from Crete, olive oil; from Kayseri, heavily spiced preserved meat pastırma (for which Kayseri is still famous today); coffee from Yemen; dates from the Middle East. From Bursa, not far from Istanbul, came many things, such as wheat, pomegranates, lemon juice, onions, chicken, and chestnuts, and from Uludağ, a mountain in Bursa, came ice and snow to make the cool drinks and desserts the Ottomans enjoyed. Bursa is still famous for many of these things today. Ankara sent pears and honey, and Izmir sent grapes and figs. Again, Ankara and Izmir are still famous for these foods today.

Food and Eating During Ramadan

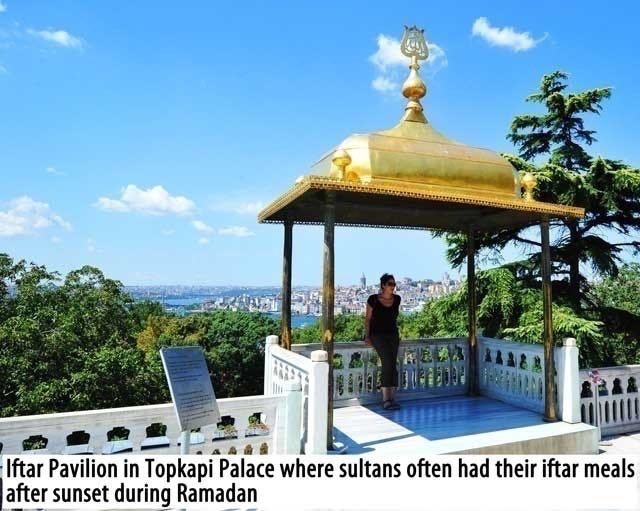

Probably the most important meals have revolved, and still do, around festivals and celebrations. The month of fasting called Ramazan or Ramadan in English, as ironic as it may be, is also accompanied by different kinds of food.

Some particular kinds of foods only appear during Ramadan, like the large flat Ramazan pidesi, a kind of bread.

The month of Ramadan is actually the ninth month of the Muslim calendar, but because it follows the lunar calendar, the Muslim calendar’s months are out of sync with the Western calendar. This is why to Westerners it seems that Ramadan is at different times every year. During Ramadan, Muslims do not eat or drink during the day; some even believe that swallowing is prohibited. Smoking is also prohibited for observant Muslims. They are also encouraged to reflect upon their life and the way they are living.

Ramadan is a holy time in which Muslims are encouraged to be charitable to one another and to make changes in their lives, such as being more generous, or making a hajj, the Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca that will help them be better Muslims. Rather than being about withdrawal, Ramadan is a celebratory time, and there are also some small carnivals and concerts, which can be enjoyed after sunset.

In Ottoman times, the month of Ramadan was a time when many charity organizations, some sponsored by the sultan himself, would provide special food for the poor people of the community. These charities would normally serve food to the poor every day, but on special occasions such as Ramadan the food they served would be a little bit nicer. Therefore, poor people would look forward to Ramadan because they could eat special meals during this time, but only after sunset and before sunrise. These charities could be found around the large mosque complexes that housed an imaret or soup kitchen. Still, it must be said that their meals were not quite as nice as those that people would prepare in their homes.