Forbidden City

Great Wall of China

Lama Temple

Beihai Park

Drum and Bell Towers

Summer Palace

Confucius Temple and the Beijing Imperial College

Tiananmen Square

Jingshan Park

History of Beijing

Chinese Cuisine and Table Manners

Chinese Traditions and Customs

Chinese Holidays and Festivals

Chinese Behavior and Etiquette

Peking Opera

Chinese Humor

Welcome to the WanderStories™ tour of the top 10 sights in Beijing: the Forbidden City, the Temple of Heaven, the Great Wall of China, the Lama Temple, Beihai Park, the Drum and Bell Towers, the Summer Palace, the Confucius Temple and the Beijing Imperial College, Tiananmen Square, and Jingshan Park. We are now ready to take you on your personal tour of these world famous landmarks.

We will also tell you the history of Beijing and several additional stories about Chinese cuisine and table manners, traditions and customs, holidays and festivals, behavior and etiquette, Peking opera, Chinese humor and jokes.

We, at WanderStories™, are storytellers. We don’t tell you where to eat or sleep, we don’t intend to replace a typical travel reference guide. Our mission is to be the best local guide that you would wish to have by your side when visiting the sights. So, we meet you at the sight and take you on a tour.

WanderStories™ travel guides are unique because our storytelling style puts you alongside the best local guide who tells you fascinating stories and unusual facts recreating the passion and sacrifice that forged the beauty of these places right here in front of you, while a wealth of high quality photos, historic pictures, and illustrations brings your tour vividly to life.

Our promise:

• when you visit these top 10 sights in Beijing with this travel guide you will have the best local guide at your fingertips

• when you read this travel guide in the comfort of your armchair you will feel as if you are actually visiting these top 10 sights in Beijing with the best local guide

Welcome to Beijing,

Beijing is the capital of the world’s largest nation and one of the most populous cities on earth. Its history is as complex or as simple as you might like it to be. The first mention of Beijing as a city is in records from the Zhou dynasty in the 11th century B.C.E. And there’s no doubt that three thousand years that have passed since then have given the Chinese people plenty of time to shape one of the most unique cities on earth. There is only one thing to do now – visit!

Let’s go!

Your guide, WanderStories

Once you have read this book please review it, we truly appreciate your feedback.

Please subscribe to the FREE WanderStories™ travel e-magazine, Armchair Travel Guide at: wanderstories.com/travel-magazine

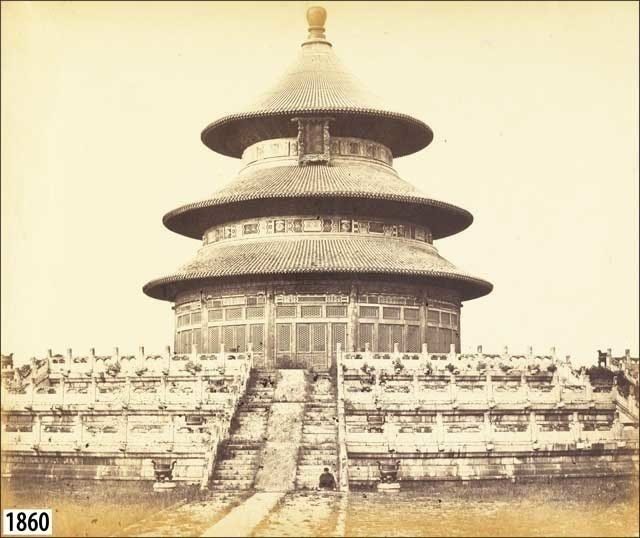

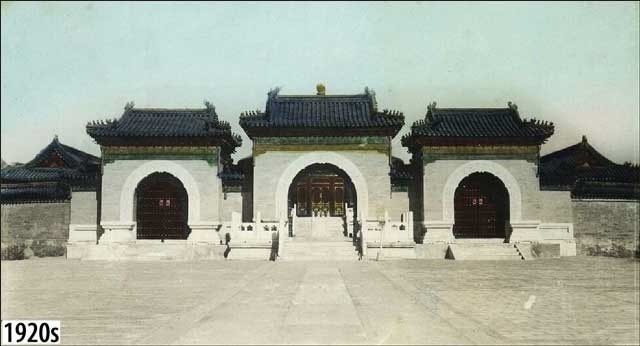

Temple of Heaven

Address: Temple of Heaven Park, Dongcheng District

Start of the tour: at the eastern entrance 39°52'57.0"N 116°24'49.4"E

![]()

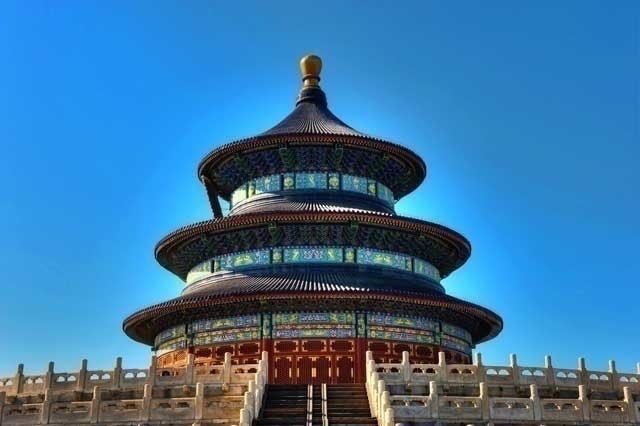

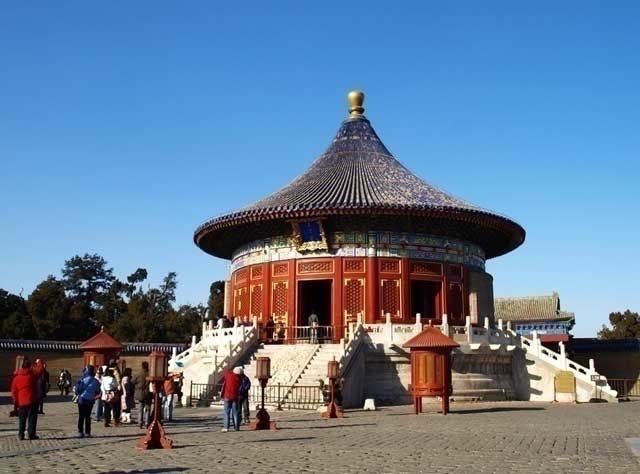

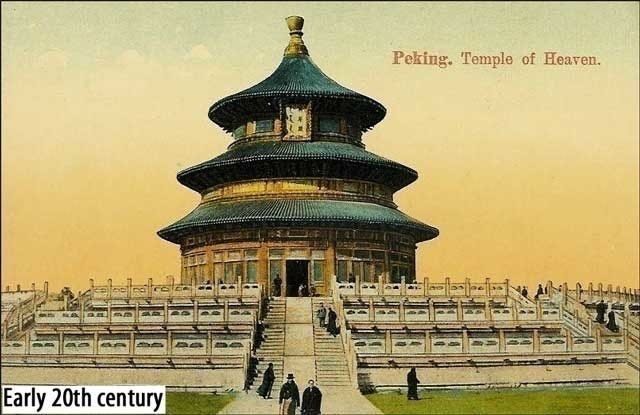

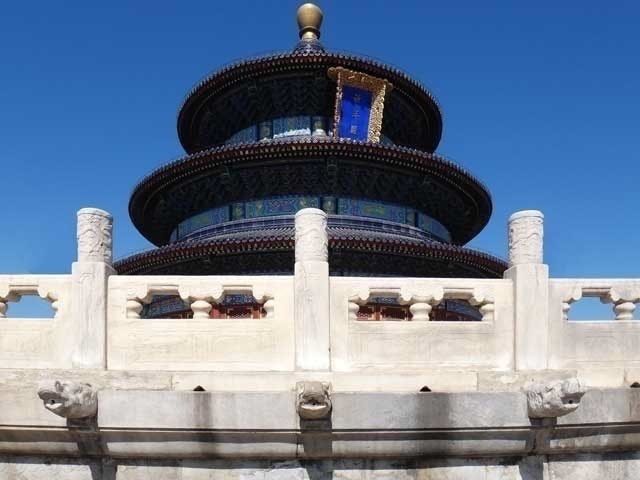

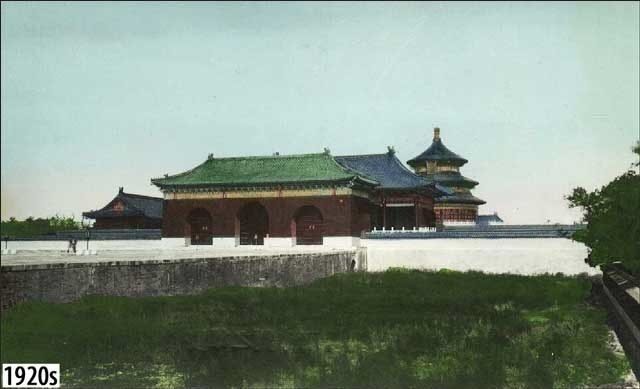

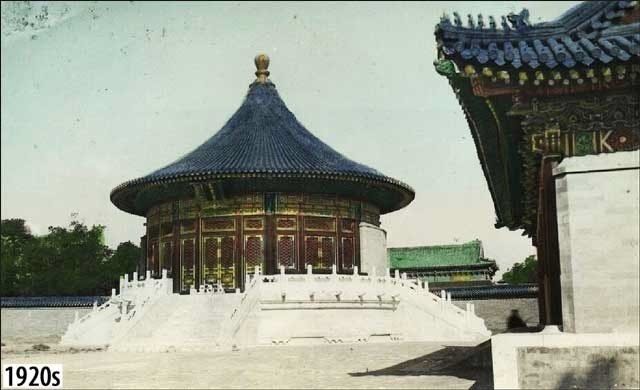

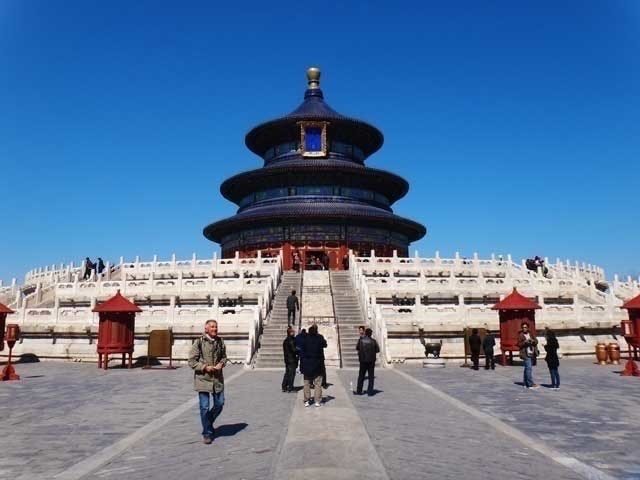

The Temple of Heaven is a majestic sight. Although not as grand or expansive as the Forbidden City, it was built in a way that would set it apart from other buildings and distinguish it as the important venue that it was intended to be.

Rightly considered one of the treasures not just of Beijing, but of China, it remains an architectural masterpiece and an important link for us to understand the practices and beliefs of the time of the emperors and the high status accorded to them. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1998.

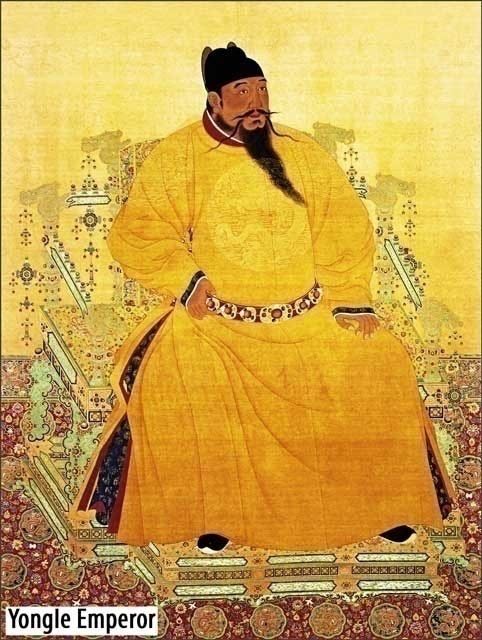

The Temple of Heaven complex was built from 1406 to 1420 by the Yongle Emperor of the Ming dynasty as a shrine dedicated to the worship of heaven.

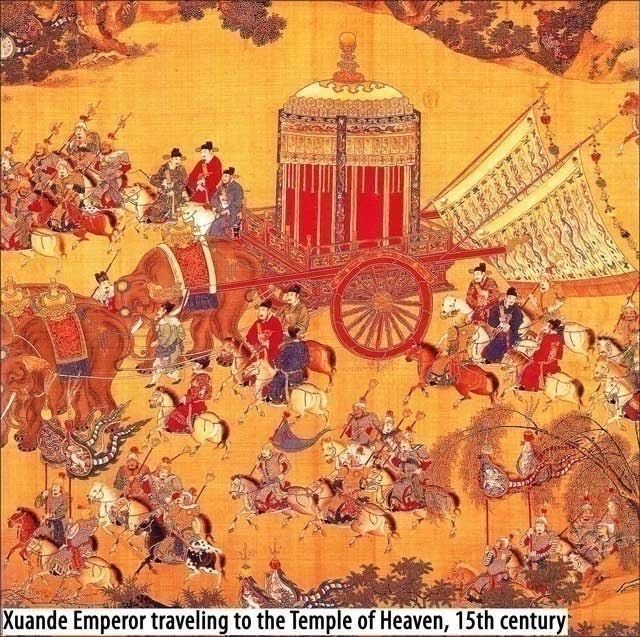

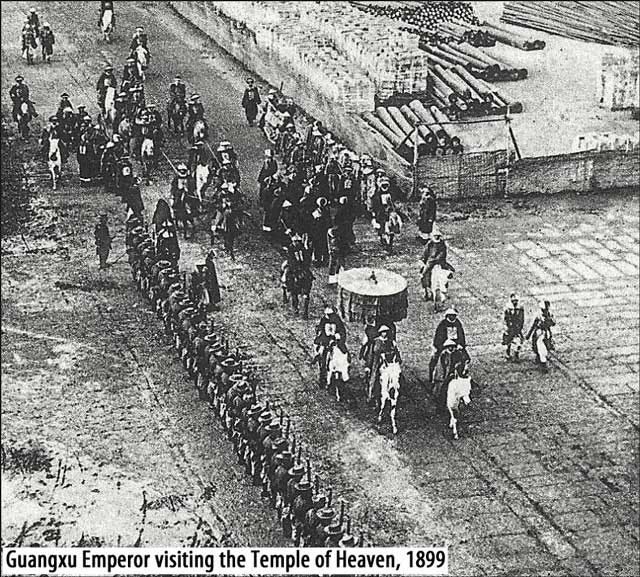

The large complex to the south of the city center was for the exclusive use of the emperor for strictly orchestrated ceremonies twice a year.

The emperor would travel here from his residences in the Forbidden City for several days at a time, to perform complex ceremonies to worship both the god of Heaven and his own ancestors, and to pray and give thanks for good harvests.

The emperor was considered by the people as the “Son of Heaven.” He drew his mandate to rule from the agreement of the gods. If he fell out of favor with the gods, their approval would be withdrawn, his dynasty would fall, and the people would suffer.

The emperor held responsibility for the actions of the gods, who had control over such things as weather, natural disasters, and crop harvests. It was to ensure good favor for these areas, and then of course his resulting support and popularity, that the emperor and his court invested heavily in buildings and ceremonies for the worship of the gods.

In many ways, this is not too different from the actions of governments today – investing in areas of importance to the people.

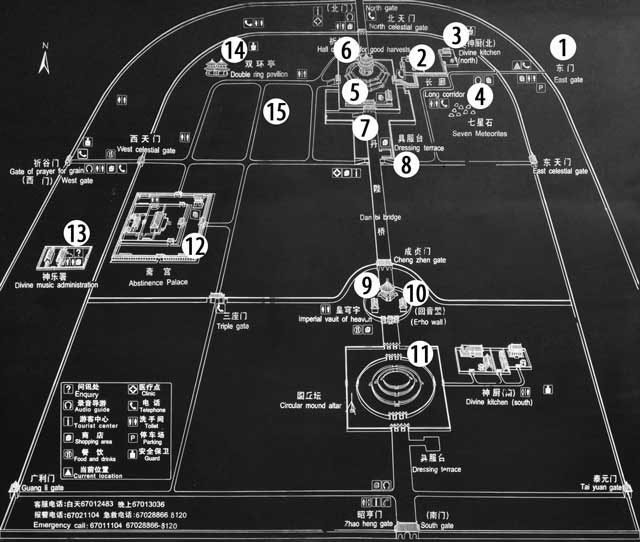

Start of the tour: at the eastern entrance 39°52'57.0"N 116°24'49.4"E

As you start the tour at the eastern entrance (No. 1 on the map) note the surroundings. Of course, you find yourselves today near the center of a bustling city; it seems remarkable that a temple could occupy such a large site here. But remember that throughout the Ming and into the Qing dynasties the city of Beijing was much smaller, and the temple complex here would have been very much in the countryside.

It has hard to get a grasp of the size of the complex, with the modern city all around it.

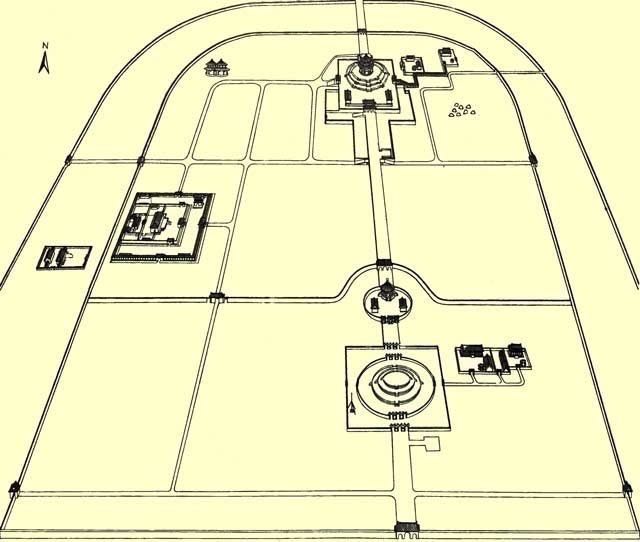

Before going into the site, let’s take a look at a map to appreciate this fully. The complex occupies 2.73 square kilometers (1.05 square miles), with walls extending for over 5 kilometers (3.1 miles) around it. Building a complex of this size gives some idea to the importance placed on it at the time. Note the shape of the walls. There are two sets of walls, a northern circular set, and a southern square set. It was believed at that time that the earth was square, and the heaven was round, so the walls were built to express this. This is the first of several such symbolisms of a round heaven and a square earth that you will see in the Temple of Heaven.

There are three main buildings, arranged along a north-south axis and linked by a raised stone walkway. These are the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvest, the Imperial Vault of Heaven, and the Circular Mound Altar. These were the main venues used for different parts of the ceremonies held here.

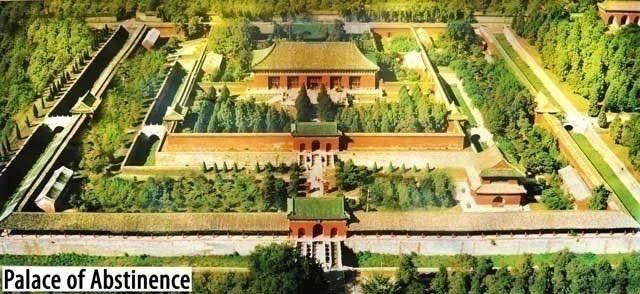

In addition, there are several other buildings. Of particular importance are the Palace of Abstinence, used by the emperor for pre-ceremony retreats, and the Divine Music Office, home to a group responsible for the complex music and performance to accompany the ceremonies. The whole site was home to a huge permanent staff with responsibility solely for the preparation and orchestration of the ceremonies twice a year.

Let’s now enter the Temple of Heaven site. The first thing you notice is the space! This was designed to be an open and spacious enclosure, with the central temples surrounded by open land and trees, enhancing the exclusiveness of the location. Many of the trees here are several hundred years old. Much of the area was planted with cypress trees, with the deep green color traditionally symbolizing respect. Such trees are often found at temple, altar, and mausoleum sites in China. It is claimed there are some 20,000 such trees in the Temple of Heaven grounds; 3,600 of them are more than 100 years old, and the oldest ones close to the main altars date back to the Jin dynasty, being some 800 years old.

The landscaping, flower gardens, and mown grass have been added in more modern times. Much of the area is now used as parkland, forming one of the largest public parks in Beijing.

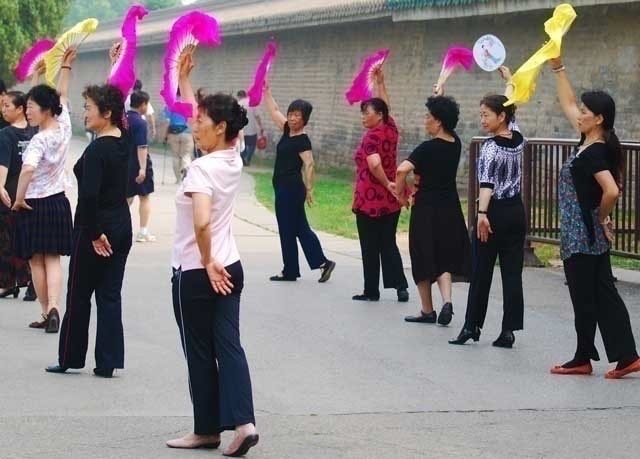

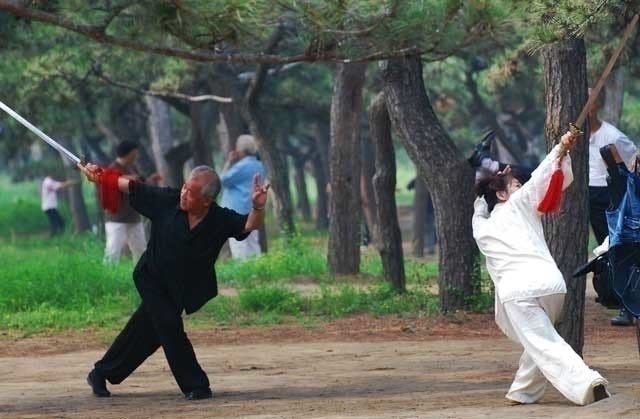

You can see many people here exercising, practicing tai chi, or dance routines, or just walking and chatting.

With its location now in a busy residential suburb of the city, this has become a popular area. It is particularly active with local residents early in the morning and later in the afternoon; it is well worth lingering here after your temple visit to enjoy some of this relaxed atmosphere. People will gather to sing, play instruments, or perhaps challenge each other to games of chess. A magnificent setting for relaxation with the temple buildings in the background.

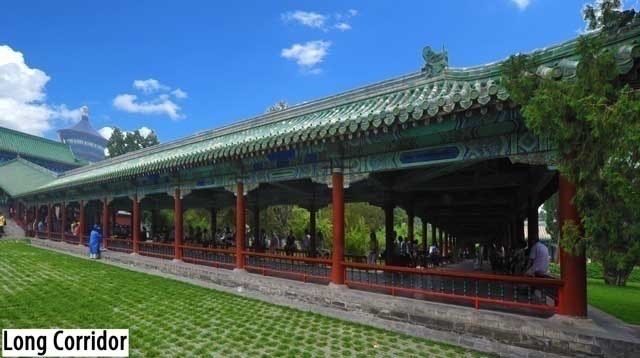

Let’s proceed now from this open park area; leading from the park area towards the ceremonial halls is an ornate covered walkway, known as the Long Corridor (No. 2).

Popular today as a convenient area for park goers to gather to play games or music, this originally held a much different function.

The Long Corridor was built to connect the temple buildings with the kitchen area (No. 3).

Offerings to heaven and to the gods were a very important part of any ceremony. In these buildings some ninety cooks and kitchen servants prepared offerings prior to ceremonies. There were some thirty different offerings, such as cereals, wines, jade and silk objects, and sacrificial cattle, prepared here and in the butcher house nearby.

This area is at the start of the Long Corridor, at the end is the main temple area. The rules for rituals prescribed that such a venue was located more than 200 paces away from where the offerings were made. It was also very important that such offerings were not contaminated in any way by wind, rain, snow, or sand, and as such, the Long Corridor was a protected route used for their transportation to the main temple.

In the evening before the temple ceremonies, the corridor would be lit with many lanterns, and all the offerings carried to the temple and altar sites as appropriate.

Before visiting the main temple buildings, let’s take a quick diversion.

Just to the south of the Long Corridor, you can see a set of large white stones arranged on the ground. What are these?

These are known as the Big Dipper Stones (No. 4). There are two stories about their origin. The first story tells that the Yongle Emperor, the Ming dynasty emperor who constructed the temple, was unable to decide on its location.

One night he dreamt that the seven stars of the Big Dipper fell from the sky and turned to stones on the ground. The next day he ordered these stones to be found and the temple to be located there.

The observant viewer will notice though that there are in fact eight stones, not seven as this legend explains. The second story of their origin clears up this problem. It is said that the first seven stones represent the seven peaks of Mount Tai, a traditional place for sacrifice and prayers to be offered to heaven long before the Temple of Heaven was built.

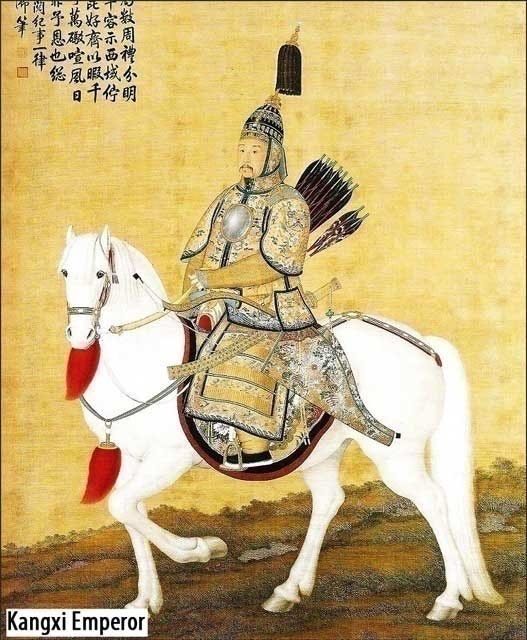

The eighth stone was then added by the Kangxi Emperor of the Qing dynasty. The Manchu ruler of the new dynasty from the northeast of China was keen to show his connection with the rest of China in the 17th century. He added the eight stone as a representation of Mount Changhai in his native region, as a symbol of unification of the country.

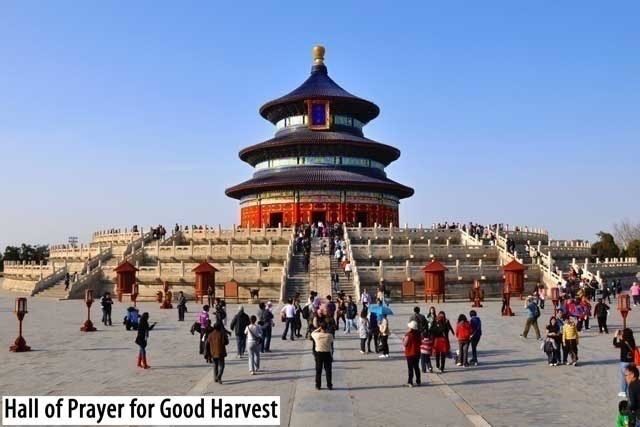

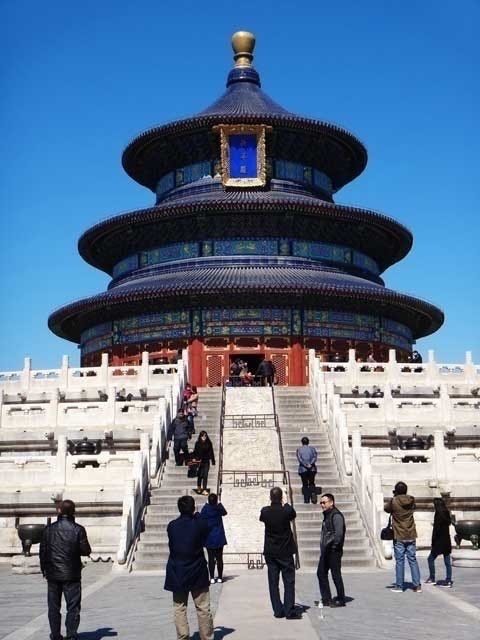

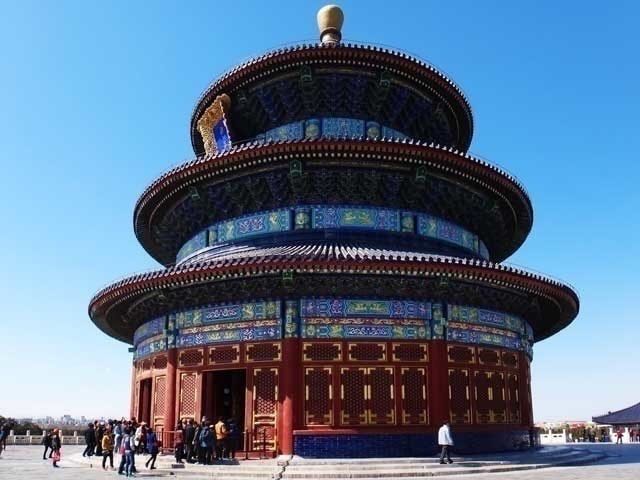

Let’s go now to the main site, starting with the site at the northern end of the main axis, the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvest (No. 5).

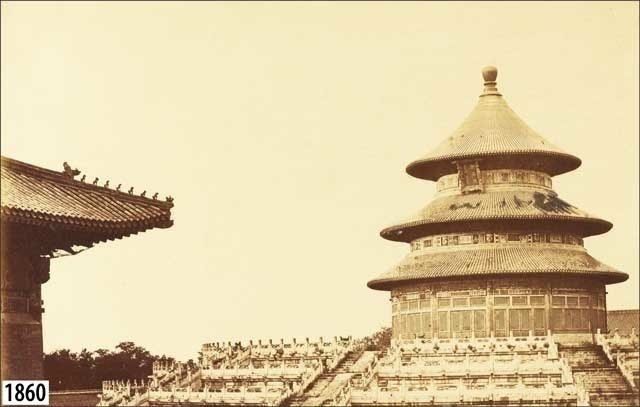

What you see today is a rebuilding of the original hall, which was struck by lightning in 1889.

With the worship of the heaven still important at that time, and in line with the belief that all ceremony had been carried out perfectly as described, one can be assured that the rebuilding of the hall followed exactly the design of the original.

This was the highest of the halls built at the temple, and in fact one of tallest ever built in imperial China. It is considered a masterpiece of ancient architecture.

The 37.5 meters (123 feet) high hall sits on a three-tiered white platform, and is an entirely wooden beamed structure; no nails or other materials were used for joints or supports in the construction.

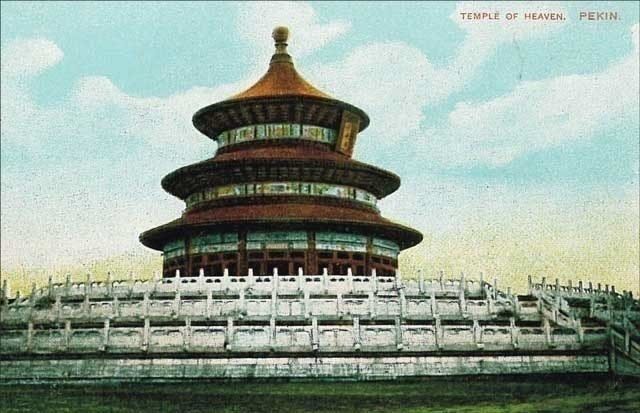

The design of the hall is full of symbolism. The round temple is built in a square surrounded by walls, giving the symbolism of round heaven and square earth.

The blue tiling on the roof of the hall represents the heaven. This is seen throughout the Temple of Heaven at the halls where prayers were offered to heaven, but not at other locations.

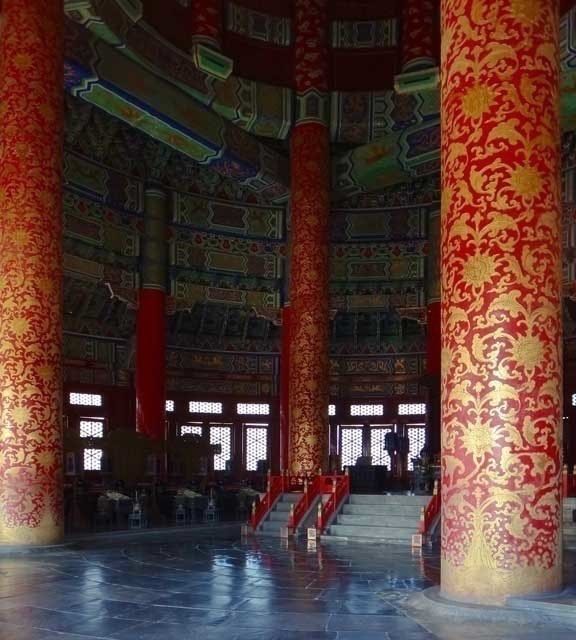

Looking inside the hall, you see 28 supporting pillars. This is not only a structural necessity, but also carries important symbolism. The concept of time and the design of the calendar was of course linked to the skies and to heaven and seen as a critical responsibility of the emperor. These pillars are laid out with 4 pillars at the most interior point representing the 4 seasons of the year; 12 pillars in the central section representing the 12 months of the year; and 12 more at the exterior representing the 12 hours of the day (equivalent to our use of 24 hours, as time was measured then in periods equivalent today to 2 hours).

The 28 pillars together symbolize the 28 xiu, or regions in the sky. These regions were used both as useful ways to memorize star groups, and also as a mapping system to record other stellar observations. In a method very similar to the zodiac system, these 28 xiu are then further grouped together into 4 groups of seven xiu, each group linked to a cardinal direction and likened to an animal representation.

The four groups thus are: for the east, Cang Long, or the Blue Dragon; for the south, Zhu Que, or the Red Bird; for the west, Bai Hu, or the White Tiger; for the north, Xuan Wu, or the Black Tortoise.

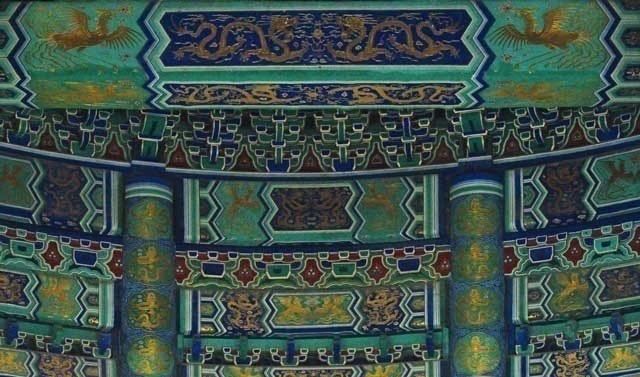

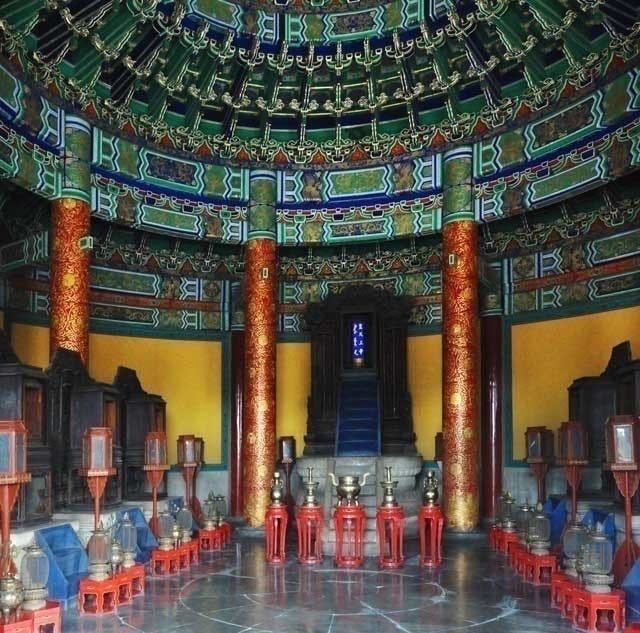

Note the ornate ceiling paintings of dragons and phoenixes, symbols of the emperor and empress.

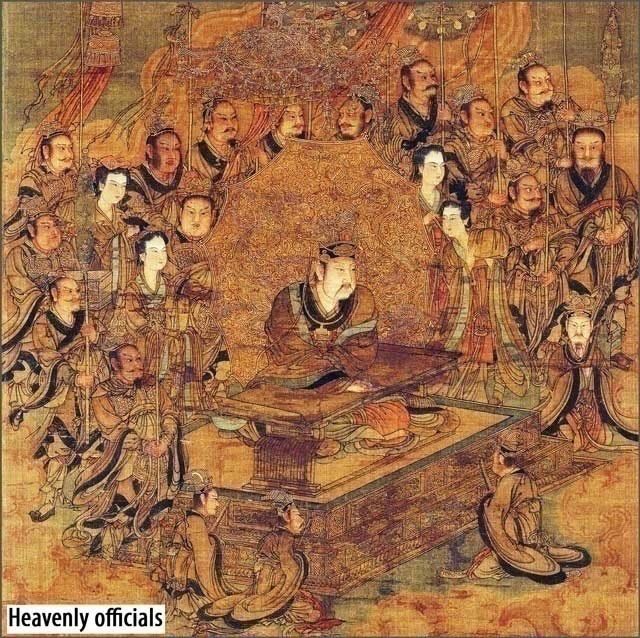

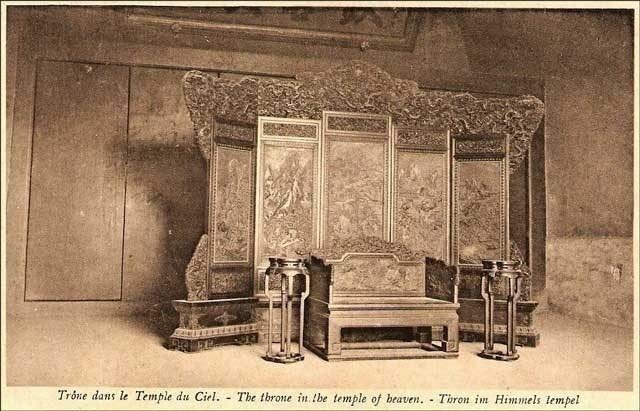

The interior is laid out as it would have been towards the end of the Qing dynasty in the 19th century. The nine thrones that can be seen in the hall explain its main use. This was where divine tablets representing the god of Heaven and eight of the Qing dynasty emperors would be placed during ceremonies.

It was common throughout imperial history to create carved stone tablets, which were consecrated as representations of gods or ancestor spirits. On these would be carved inscriptions bearing the names of, and dedications to, the gods.

You may wonder why so much importance was placed here on the ancestors of the emperor. This is in line with the belief that the ruling emperor was considered the “Son Of Heaven.” After death, the previous emperors became gods in their own right, joining the other gods in monitoring and giving approval for the current emperor’s actions.

The tablet representing the god of Heaven would be raised on the high central throne, with the eight tablets for the previous emperors arranged alongside. The tables and containers placed in front of each of the thrones were used to hold the sacrificial offerings presented to each of the gods.

The containers used for offerings at the temple were highly specific, following strict regulations for their size, design, and color. Here, at this hall, the containers were always round and colored blue, both symbolizing the heaven. The materials used varied and included pottery, bamboo, jade, gold and silver. The containers would be placed on embroidered silk. These silks would again follow a strictly defined set of designs and colors; this time they would vary depending on whom the offering was intended for.

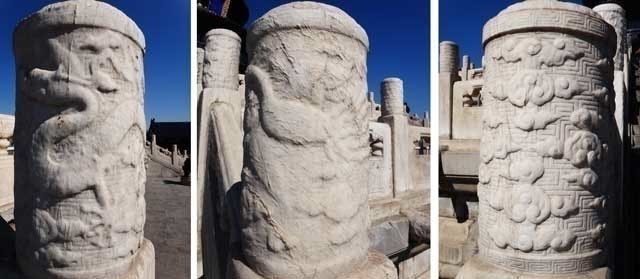

Let’s go back outside. Take a closer look at the platform the hall stands on. There are many design and symbolism elements here too. Each of the three levels takes a theme for the design of the balustrades and also for carvings on the main north and south stairways used by the emperor.

The lower level is designed with clouds, the middle with phoenixes, and the higher level with dragons; as the symbol of the emperor dragon always takes the highest placement.

It was in fact a serious crime to create any design that did not follow this rule.

Around the main temple building are three other halls. What were these used for? These were not used as part of the main ceremony here but were further locations for the tablets representing the gods and previous emperors.

The northern hall, the Imperial Hall of Heaven (No. 6), was used as a location to house the main tablets of the god of Heaven and the previous emperors before the ceremony.

On the day before the ceremony, the emperor would come to this hall and, amongst an incense-filled atmosphere, offer prayers and greetings.

Following this, the tablets would be transferred by the officials to the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests.

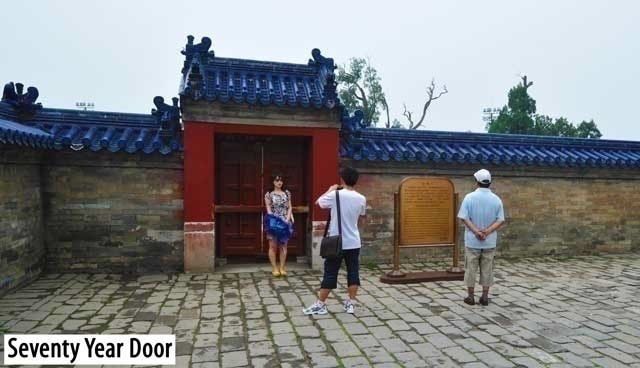

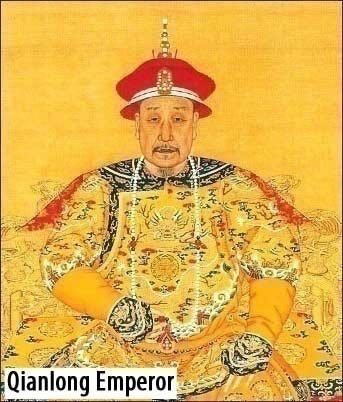

This hall has an interesting addition, adding a small amount of humility to the scene. There is a door in the corner of the courtyard, known as the Seventy Year Door.

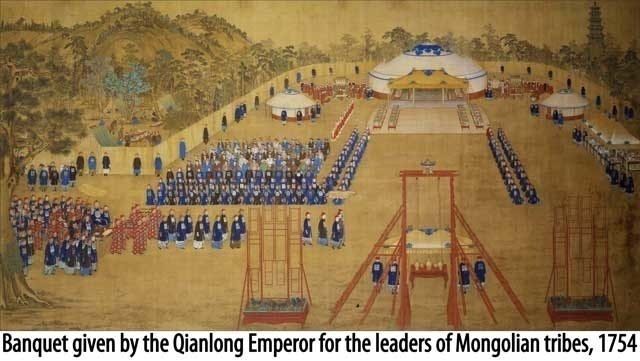

This was added by the Qianlong Emperor, the longest serving of any of the Chinese emperors. He ruled almost 64 years during the 18th century.

In his old age and weak health he used this door to shorten his walk to the halls. Fearful of breaking tradition he made a decree that none of his descendants should ever use the door before they reached seventy years of age. None ever did, and he was the only person to ever use it.

The two halls to the sides of the courtyard were used to house the tablets of other attendant gods during the ceremony.

So, you have now explored the hall and the courtyard, the remaining question is when was this hall used? In fact, only once a year. It was without doubt one of least used halls in Beijing, yet one of the most important! This is a good point to discuss the ceremonial activities that would have been held here.

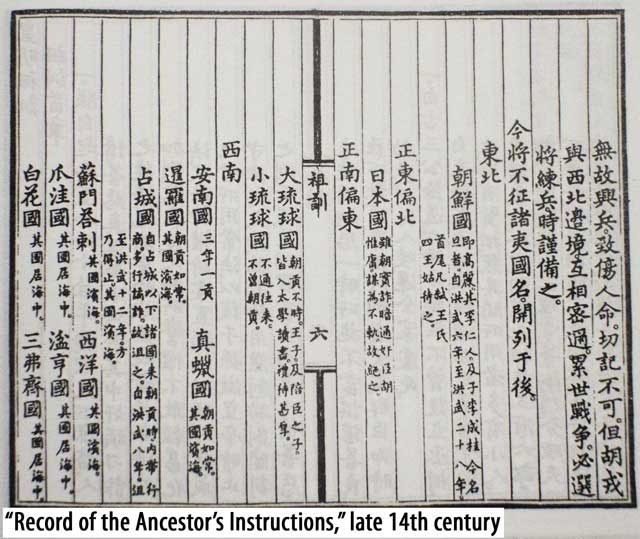

When it was originally built in the 15th century by the Yongle Emperor, the temple complex was designed for the worship of both heaven and earth.

During the first half of the 19th century the Jiaqing Emperor built separate temples elsewhere in Beijing for the worship of the earth, the moon, and the sun. This temple was then converted to be used for just the worship of heaven, and this is the state you find it in today.

The practice of worshipping heaven is an ancient one, in existence long before the Temple of Heaven was built. There is evidence in China of worshipping heaven and accompanying formalized ceremony taking place as early as 2,000 years ago.

In imperial China, this worship was an important affair. It was overseen by the Ministry of Rituals, an entire division responsible for the preparation and carrying out of such ceremonies. Everything had to be done exactly as prescribed, any deviation or mistake in the proceedings could negate the effect and lead to disastrous results – both for the success of the harvest and the popularity of the emperor.

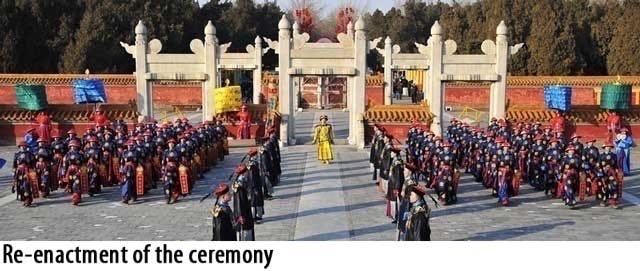

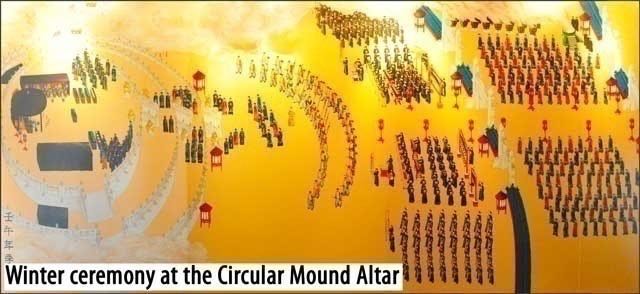

There were two ceremonies carried out each year at the Temple of Heaven. One was held in the spring to pray for a successful upcoming harvest and good crop yield. The other was held at the winter solstice, to give thanks to the gods for the year’s harvest, and to update them on the events of the year.

The spring ceremony was focused mainly at the hall you have just visited, the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvest. The emperor and his officials would spend two days at the temple during this time, with the first day dedicated to preparation of food and other offerings, personal inspection of everything to be used in the ceremony by the emperor, and private greeting ceremonies with the emperor and the divine tablets to welcome the gods and his ancestors.

The winter ceremony was arranged differently. This was focused at the southern area of the temple complex, at the Circular Mound Altar. This ceremony was much more gloomy, involving a complex process of animal sacrifice and deity worship, taking place in the late night in the middle of winter.

The emperor would reside in the Palace of Abstinence, undertaking a short period of fasting before the main ceremony was held in the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvest.

Offerings of cooked food, grain, fruit, silk and jade would be made to each of the representations of the god of Heaven and of the emperor’s ancestors. Following a strict regime of prayer in the hall, the offerings would then be burnt under the watchful supervision of the emperor, the smoke carrying the offerings and prayers up to the heaven.

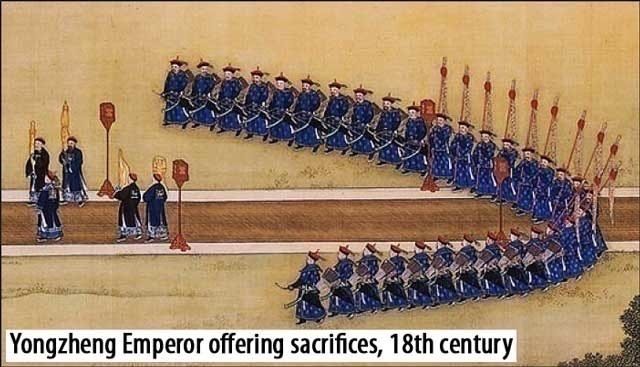

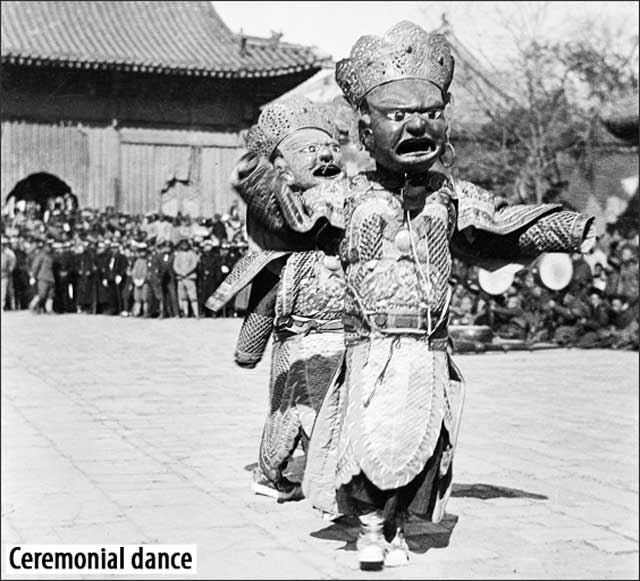

The ceremony would be accompanied by much music and dance. Two groups of 64 dancers would perform whilst the emperor offered prayers and sacrifices.

There were three separate performances that would take place as part of this spring ceremony, each accompanying a different set of offerings that the emperor would make. The first was a strong, masculine dance with dancers wielding shields and axes. This symbolized longevity, and was carried out whilst the emperor made the first set of offerings. The second set of offerings would be accompanied by a more elegant dance with dancers carrying fans, and symbolizing peace.

The final dance act accompanied the last offerings and was again a stronger, masculine dance; this time demonstrating lasting peace and good wishes for the gods.

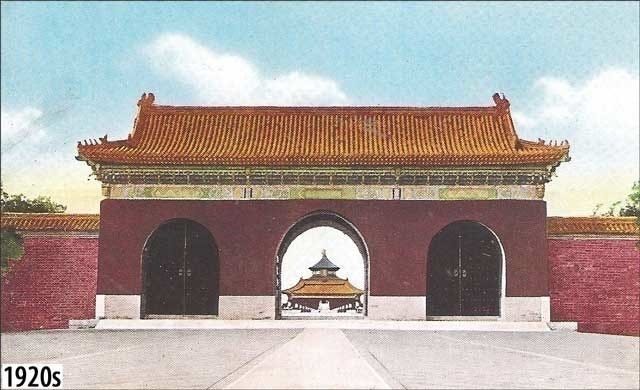

Let’s leave the northern complex and the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvest through the imposing gateway and move south on the elevated causeway.

As you leave, note the closed central doorway of the gate. This central entrance was reserved for the use of the god of Heaven, the emperor would use the door to east, and the officials would use the door to the west.

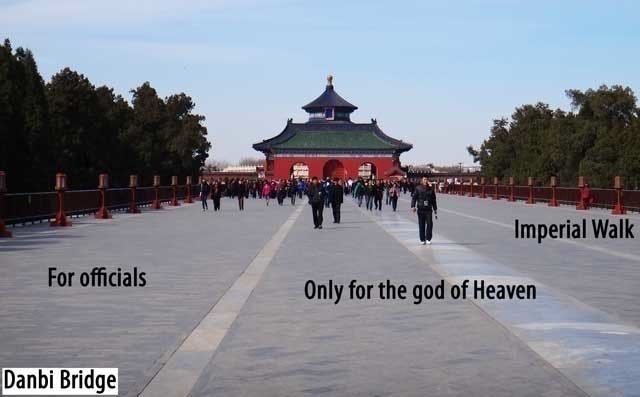

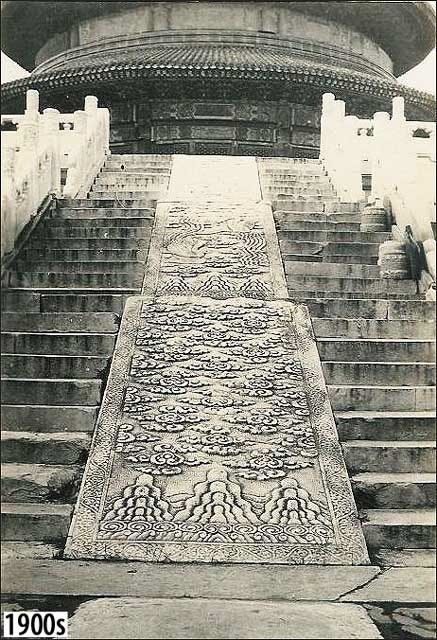

Connecting the halls along the main north to south axis is a white stone causeway, called the Danbi Bridge, or the Red Step Bridge (No. 7).

It is 360 meters (1,181 feet) long and was used as the main route at the time of the ceremony. Looking at the path’s surface you can see it is divided into three sections. Just as you saw with the gate leading here, the central of these sections was for the exclusive use of the god of Heaven, not even the emperor could walk here. He would use the path to the eastern side, known as the Imperial Walk, whilst accompanying officials would use the path to the western side. Note, of course there was no path for ordinary people. At many temples, you can find doors or paths for the use of the common people; here they were never allowed even to enter, so there was no need for a path for them. You should feel lucky to be allowed to use any path today!

Why is it referred to as a “bridge” you many wonder? At first sight it doesn’t appear to be crossing any road, pathway, or river, so why use the description “bridge”? Well, it did in fact serve as a bridge, and an important one, at the time of ceremonies.

The animals to be sacrificed to the gods were raised in the southwest area of the temple grounds. With the slaughterhouse and kitchens located to the eastern side of the grounds, the animals had to cross this walkway. Being of much lower status than those who could use the walkway, the animals symbolically had to pass underneath it, through an archway towards the northern end. This was in fact a difficult task. To show respect, it was absolutely forbidden for the animals to touch the bridge in any way.

You can imagine the challenge of getting wild animals to pass underneath in this way!

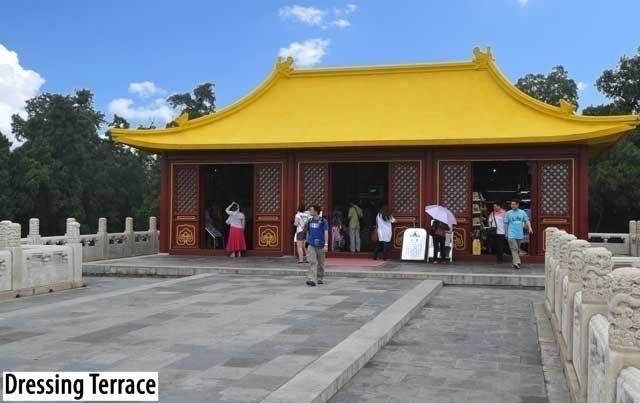

On one side, there is a bright yellow roofed pavilion, called a Dressing Terrace (No. 8). This is a modern construction representing a yellow silk tent, which would have been erected here at ceremony time for the emperor to change clothes on his way to the Circular Mound Altar. He would change from his traditional yellow imperial robes into the blue robes used for ceremony; blue of course being the representative color of heaven.

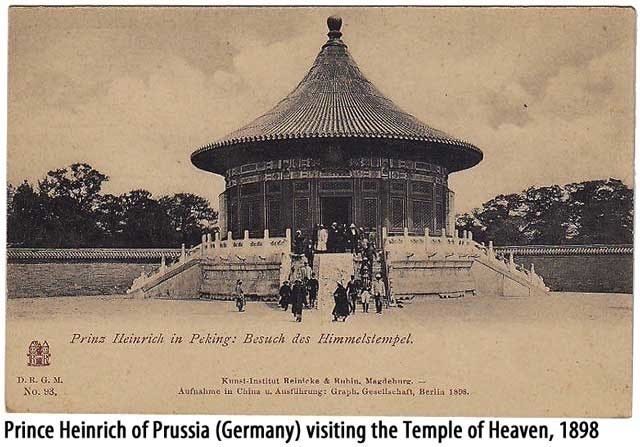

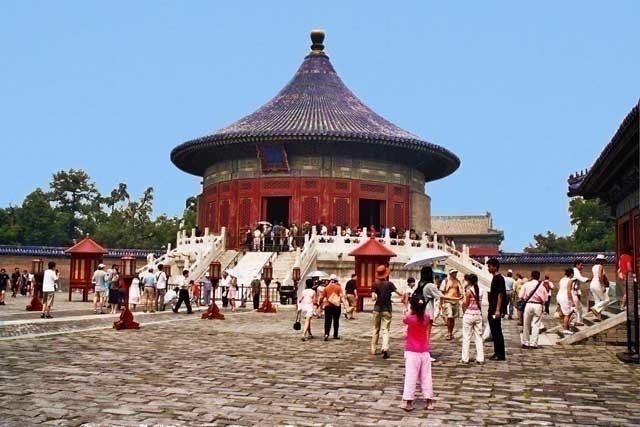

Let’s look now at the structures at the southern end of the Danbi Bridge – the Imperial Vault of Heaven (No. 9).

At first glance, this appears much like a smaller version of the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvest. Its use, though, was in fact very different.

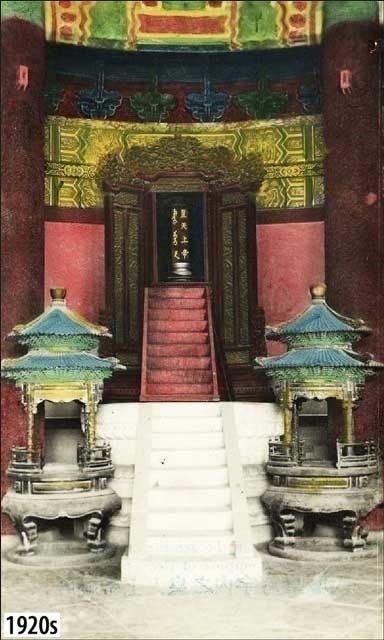

This would not be used as a temple or prayer hall during the main ceremonies. Rather, it was a sacred location for the storage of the divine tablets representing the gods and the emperor’s ancestors.

These tablets were only put into their places at the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvest for the spring ceremony or the Circular Mound Altar for the winter ceremony just before the proceedings. For the remainder of the year, they would reside in this hall.

At the winter ceremony, the emperor would also come here on the day before the ceremony to pray to the gods and ancestors and to welcome them to the upcoming ceremony.

The Imperial Vault of Heaven was home to the tablets of the god of Heaven and to the emperor’s ancestors.

Note the carving on the central stairway leading to the Imperial Vault of Heaven. This is one of the most elaborate in Beijing, and features a detailed carving of two dragons playing with a pearl.

Inside you see the central throne and side thrones similar to the layout in the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvest.

The two smaller halls to the sides of the Imperial Vault of Heaven were home to the tablets of other gods.

The East Hall housed the gods of the Sun, Stars, and Planets; the West Hall housed the gods of the Moon, Cloud, Rain, Wind, and Thunder.

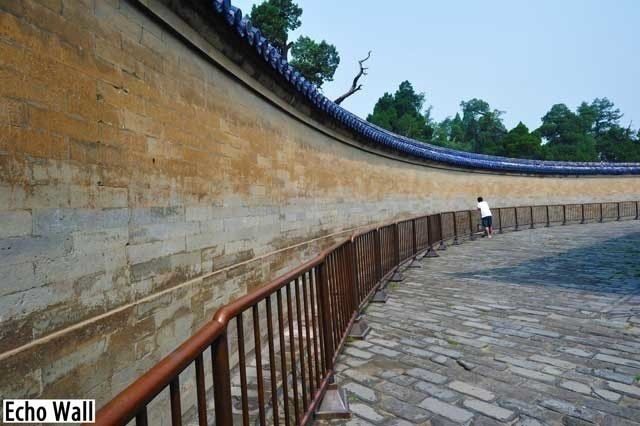

The circular wall surrounding the enclosure here is known as the Echo Wall (No. 10), due to its unusual acoustic properties. It is said that even a whisper made at any point on the wall can be heard at any other point. Certainly worth trying, although usually there are so many people doing the same it somewhat diminishes the effect.

The purpose here was to reflect the words of the emperor up to the heaven. He would talk here to the gods before the ceremony, and give updates on the events of the year. These words would be amplified as they were carried up to the sky.

But now, let’s move on. Notice, how the middle door of the gate that leads out is again closed, reserved for the god of Heaven.

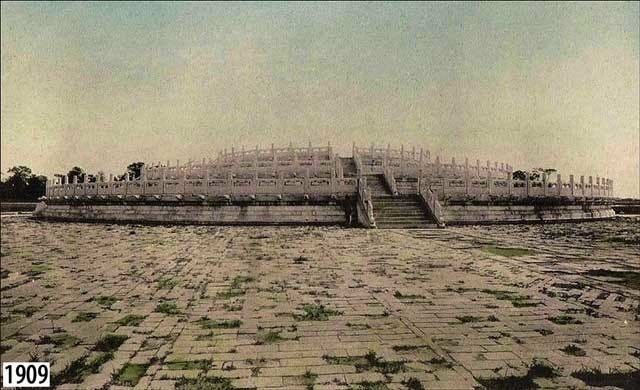

The next destination is the Circular Mound Altar (No. 11).

The design of the altar is highly symbolic. Note again the repeated representation of the heaven and earth with the round altar enclosed in the large square walled courtyard.

Like the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvest, it only saw use on this one occasion each year.

Another symbolism, there is also much use of the number 9 in the design and build.

This was at the request of the emperor, who ordered it to be built with as much use of this number as possible.

The number 9 has an important significance.

In traditional Chinese Daoist belief of yin and yang, the odd numbers represent yang, which is also the stronger, masculine side, and the representation of heaven (yin is the representation of the earth).

As the highest odd digit, 9 is the most significant representation of heaven, and it is used as a symbol for the emperor – the Son of Heaven.

In a less philosophical way, 9 has also long been revered in China for its pronunciation jiu, which is the same as the pronunciation of the word for “longevity.” This type of association of words by their pronunciation is very common in China still today.

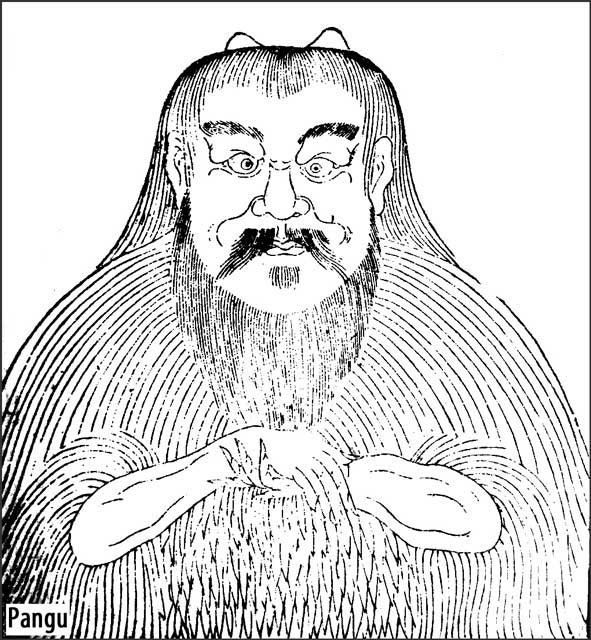

Perhaps now is a good time for a brief detour into Chinese mythology. It states that in the beginning there was nothing in the universe except a formless chaos. However, this chaos came together to form a cosmic egg. Within it, the perfectly opposed principles of yin and yang became balanced and Pangu (literally “Plate Ancient”) emerged from the egg. In Chinese folklore Pangu is usually depicted as a primitive, hairy giant with horns on his head.

Pangu set about the task of creating the world. He separated yin from yang with a swing of his giant axe, creating the earth (yin) and the heaven (yang). To keep them separated, Pangu stood between them and pushed up the heaven. This task took 18,000 years. With each day the heaven grew 3 meters (10 feet) higher, the earth 3 meters (10 feet) wider, and Pangu 3 meters (10 feet) taller. In some versions of the story, Pangu is aided in this task by the four most prominent beasts: the Tortoise, the Qilin, the Phoenix, and the Dragon.

After the 18,000 years had passed, Pangu was laid to rest. His breath became the wind, mist, and clouds; his voice the thunder; left eye the sun and right eye the moon; his head became the mountains and extremes of the world; his blood formed rivers; his muscles the fertile lands; his facial hair the stars and Milky Way; his fur the bushes and forests; his bones the valuable minerals; his bone marrows sacred diamonds; his sweat fell as rain; and the fleas on his fur carried by the wind became the fish and animals throughout the land.

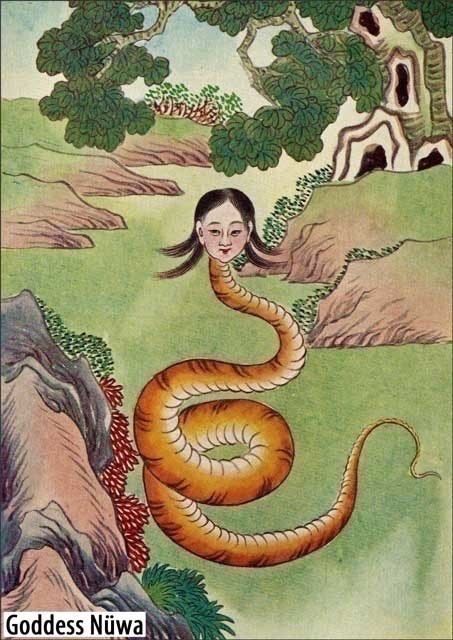

Goddess Nüwa then used the mud of the water bed to form the shape of humans. These humans were very smart since they were individually crafted. Nüwa then became bored of individually making every human so she started putting a rope in the water bed and letting the drops of mud that fell from it become new humans. These small drops became new humans, not as smart as the first.

Now back to the temple. You can see the four stairways leading up to the altar, each level naturally having 9 stairs.

As you climb the altar, notice that despite the different heights of each level of the altar, each stairway has 9 stairs, of differing size.

There is a single central stone in the middle of the top level. Surrounding this is a circular ring of 9 further stones. Surrounding that is a second ring of 18 stones, followed by one of 27 stones, and so on up to the 9th ring, which contains 81 stones.

This use of multiples of 9 is repeated in the middle and lower levels of the altar as well. The middle level starts with a ring of 90 stones and ends with a ring of 162 stones; the lower level starts with a ring of 171 stones and ends with a ring of 243 stones. All totaled there are 3402 stones, of course a multiple of 9! There is a saying in Beijing that: “Nine is everywhere at the Temple of Heaven.” It would seem so!

The central stone on the upper level is also very important. It is known as the Heavenly Center Stone, and was the place where the emperor would stand when making reports to the heaven. It is so placed that when speaking there, the sounds bounce off the balustrades and walls of the complex and create multiple echoes. This gives the effect of many people speaking. And these amplified words of the emperor were carried to the heaven.

The triple tiered platform of the Circular Mound Altar was the main location for the ceremony held at the winter solstice.

Try to get a feeling for the atmosphere of the ceremony. Remember it would always be held before dawn, at the winter solstice. Dark, and very cold, possibly quite different to how you feel it here today!

The ceremony here would be a gloomy, but impressive sight.

Look at the empty space all around the altar; this would be used by the attendant ministers, as well as many musicians and dance performers, an important part of the ceremony.

How would the ceremony have proceeded here? Early in the morning before dawn, the emperor would leave his temporary residence in the nearby Palace of Abstinence, and a bell would be sounded from there to signal the beginning of the proceedings. The altar would have been prepared by the Ministry of Rituals during the night before. As with the ceremony at the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvest, everything had to be prepared and the ceremony had to be carried out exactly as prescribed; any deviation could be disastrous.

Three large lanterns would have been lit and hung above the courtyard to watch over the proceedings. These were known at the Watching Lanterns. The large timber construction you can see to the side of the courtyard was used as a lamp post and is the only one of the original three, which remains today.

These lanterns would of course provide light for the early morning ceremony, but there were also many thousands of small lanterns placed around the altar. Like all other aspects of the ceremony, the design and layout of these was strictly specified. For example, the lanterns that would sit closest to the gods’ tablets would be shaped like a ram’s horn and decorated with gold thread. One record of the time describes the scene this created: “One lantern shines and ten thousand lanterns light like stars in the sky.”

One story about these lanterns demonstrates how important it was to follow the protocol exactly. It is said that during one ceremony in the Qing dynasty, the Qianlong Emperor noticed that one of the Watching Lanterns had not been lit. The officials in charge of these lanterns were exiled from the capital, and those responsible for the overall preparation were also severely punished.

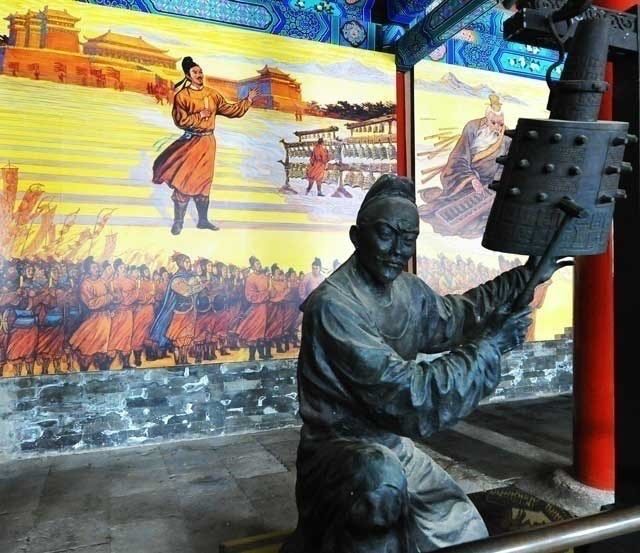

The ceremony would begin with music and dance performed in the large open square, with the purpose of summoning the gods to attend the ceremony. This was a very particular type of music known as Zhonghe Shaoyue, a style with its origins deep in the ancient rituals of heaven worship. The music was stylized to represent a conversation between man on earth and the heaven. The story of this music can be understood, and examples heard, at the nearby Office of Divine Music.

With the gods and other heavenly officials now in attendance, the first offering would be made to them through the ceremonial sacrifice of a cow. This cow would have been killed beforehand in the sacrificial kitchen, in another ceremony where it would have been beaten to death before being inspected by the emperor. It would then be prepared to be burnt in the sacrificial oven, located just to the south of the altar. Before it was burnt, it would be shaved, and the blood would be drained.

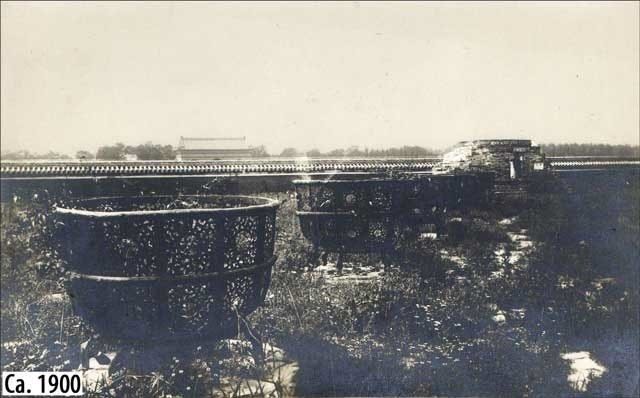

The sacrificial oven is still in place today. It is a green tiled construction just next to the south gate of the altar. The round green tiled pit next to this would be where the hair and blood of the cow was buried.

This sacrifice of a cow would be the only such animal sacrifice to take place as part of the ceremony. Other meat would be included in the offerings prepared and left for the gods, along with vegetables and alcohol.

Under the presence of the lit lanterns, and with the burning of much incense in large burners placed around the courtyard, the emperor would then give a formal salute and offer prayers to the god of Heaven and to his own ancestors. The representative tablets would have been placed beforehand on the top level of the altar, and a series of offerings of food, silk, jade, and wine would now be brought to each of the gods. A lengthy service would follow, with musical accompaniment, whilst the emperor read a series of ceremonial declarations to the gods.

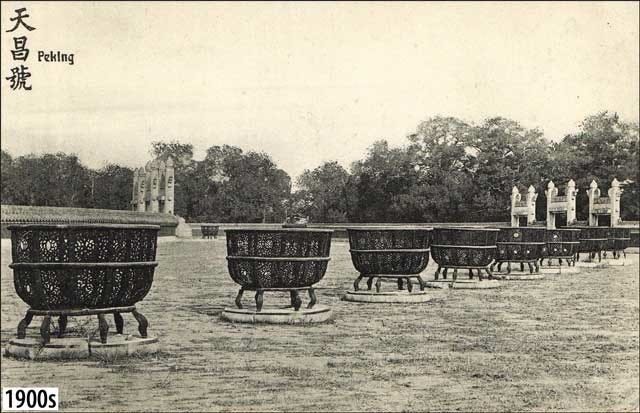

Once the devotions had been completed, all of the offerings made would be removed and taken to the series of iron stoves to the south of the altar.

There, under the strict supervision of the emperor, these offering would be burnt in dedication to the gods; the smoke carrying the offerings up to the heaven.

This would mark the end of the ceremony and the end of three days residence at the temple for the emperor, who would then return to the Forbidden City.

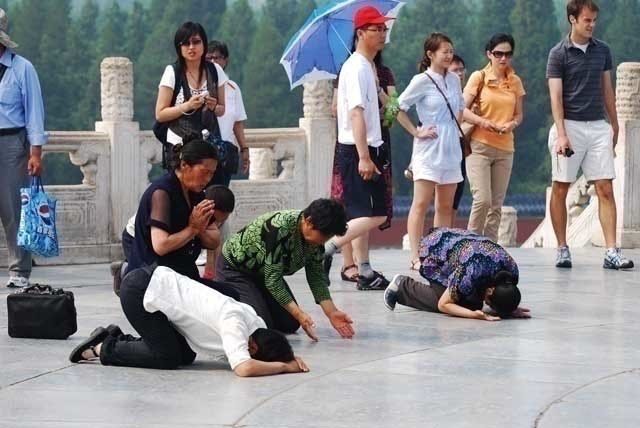

Today, there are no more emperors, and ordinary people come here to pay their respect to the heavenly gods.

Now that you have a much better understanding of the uses of the different locations in the Temple of Heaven, and of the ceremonies held here, let’s leave the Circular Mound Altar, and the central body of halls for worship, and explore a few of the other important locations in the Temple of Heaven complex.

The large separate area, called the Palace of Abstinence or the Fasting Palace (No. 12), to the western edge of the Temple of Heaven site, was used for fasting before the ceremony by the emperor and his attendant close ministers.

The official entourage would visit here before each of the two annual ceremonies. At the spring ceremony, a short stay of just one day would be made, but before the winter ceremony they would reside here for three days.

Whilst in residence, a strict fast was observed as described in the protocols for official ceremony. The emperor would purify himself by abstaining from meat, alcohol, onion and garlic. He would also have to avoid the distracting activities of state affairs and his concubines, focusing his mind instead on prayers and meditation.

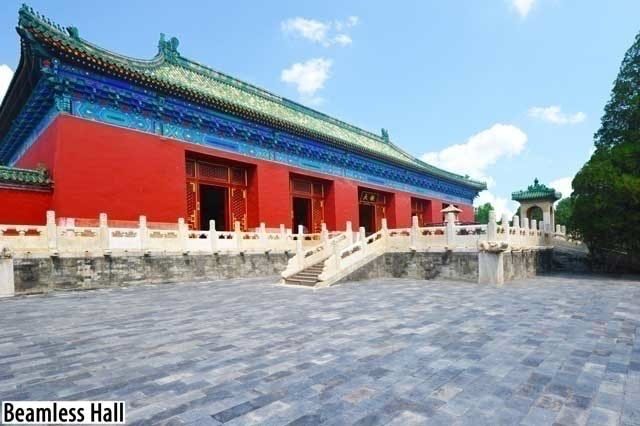

Entering the area you come first to an open courtyard with the main hall called the Beamless Hall.

This was used as prayer hall and for meetings between ministers. On the terrace in front of the hall, you can see a couple of interesting objects.

The small copper figure to the right was placed here when the emperor was in residence. It would have contained in its hands a small replica of the abstinence tablet, a divine tablet explaining the rules and importance of abstinence. This would serve as a constant reminder to the emperor of the importance of his duty here.

It is believed that the figure is based on Wei Zheng, an upright and outspoken minister of the Tang dynasty.

To the left is a “time keeping device.” Before the ceremony the officials from the Ritual Administration and the Celestial Administration would deliver their report on the ritual’s schedule to the officers here, who would forward it to the emperor. The time for ceremonies to begin was fixed at “seven quarters before the sunrise,” which corresponds to about a quarter past four in the morning.

Inside the hall you can see several “Dragon Pavilions.” These were used to transport prayer tablets from the Forbidden City to the Temple of Heaven before the ceremonies.

The inscription above the throne is written by the Qianlong Emperor, and translates as: “Admire and Respect the Heaven,” another strong reminder of purpose for the occupants of the hall. The central room here was where the emperor would meet ministers during the fast; the rooms to the sides were used as resting halls for the ministers.

The hall here is known for its unusual construction technique, resembling many of the wooden beamed halls seen elsewhere; it is in fact built with no structural wooden beams, but using arches inside for its stability; hence its name, the Beamless Hall.

Behind the main hall are the residential quarters of the emperor. There are separate rooms here for spring and for winter. The central room was used for the emperor to meet his ministers.

There is also a lounge and study room where many emperors would come to compose poetry whilst in residence here. This was a particular favorite pastime of the Qianlong Emperor who wrote much poetry here. There would also have been a place here for the emperor to bathe; part of the preparations he would undertake the day before the ceremony.

Before moving on, note the almost fortified design of the complex. Surrounded by a double moat and with high walls, this highlights an important concern in imperial times – that of the safety of the emperor. Throughout imperial history, there were several attempts to murder ruling emperors, and this was a constant fear.

There is an interesting tale involving the Yongzheng Emperor of the Qing dynasty who ruled in the first half of the 18th century.

Despite the apparent high security of the halls here, he was so fearful of attempts on his life that he refused to stay overnight. Instead, he had a Hall of Abstinence constructed within the Forbidden City. Before the main winter ceremony, he would conduct his fasting there, only returning to the hall here a few hours before the ceremony was due to begin, thereby complying with the strict requirements of the ceremony without overly endangering himself.

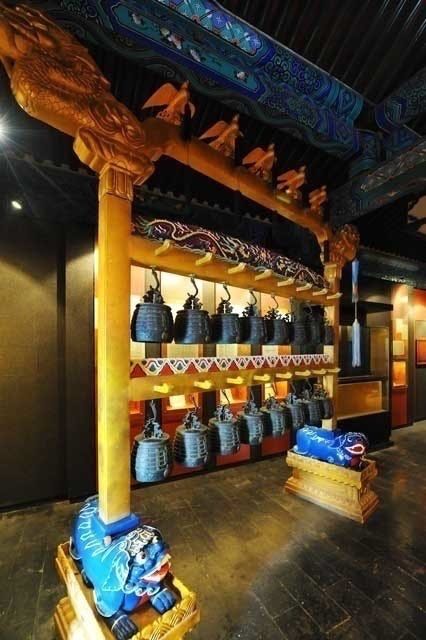

To the west, behind the Palace of Abstinence you find the Office of Divine Music (No. 13).

This separate large complex was used for the preparation and rehearsal of the music and dance used as part of the ceremonies. The size and devotion of this goes some way to demonstrating the importance of the ceremonial activities.

There would have been a year round staff present here, responsible for ceremonial rehearsal and training of new musicians and dancers. They would perform of course only twice a year, but to exacting precision.

Singers and dancers were chosen at a young age and would train here for many years. Experts were employed to perfect each area of the music and performance. The large and permanent staff made this a busy part of the complex.

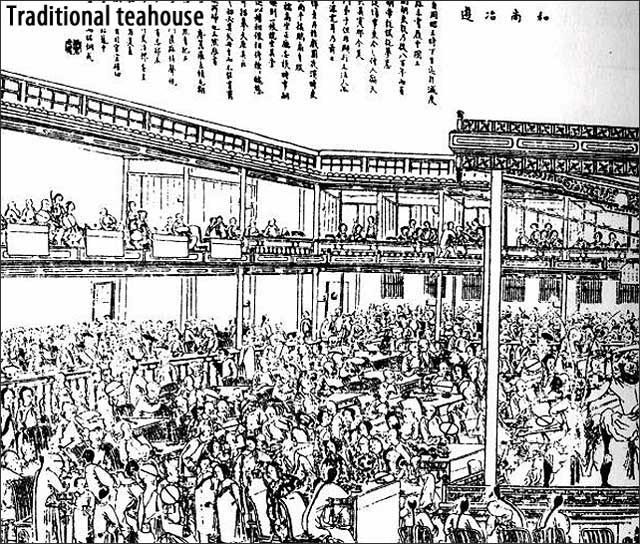

While the rest of the site was off limits except for specific purposes, this area saw a constant stream of visitors and tradesmen, and was home to a variety of stores and small business.

The halls here today contain an extensive collection of the instruments used in performances, along with good descriptions of the musical styles.

Take your time to look around here.

Perhaps most interestingly you can listen to examples of the music that would have been performed during the ceremonies. Simple and uplifting in style, try and imagine this as it was intended – as a communication bridge between the earth and heaven.

Let’s now explore further the extensive gardens and parkland of this magnificent temple complex. As we discussed, the use of this area as one of the major public parks in Beijing makes for some good relaxed exploration. But there are some more dedicated attractions here as well.

The area contains several pavilions. Great places to rest of course, but some of these also have interesting histories.

The Double Ring Pavilion (No. 14) in the north is one of the best such examples. This was moved here in 1975 from the government complex of Zhongnanhai next to the Forbidden City, to enable more people to see and appreciate its design and beauty. It was built in 1741, a gift from the Qianlong Emperor to his mother on her 58th birthday.

Beautiful in design, it is built as a single structure but resembling two interlocking traditional pavilions. Appearing differently when viewed from different angles, from straight on it resembles a pair of peaches; the small steps to the front even representing the sharp points!

In recent times, there has been much development of the area. There are some beautiful landscaped areas that have been added, including an extensive rose garden (No. 15), claiming to hold over 100 different species of rose.

While you wander around, if you are lucky, you may encounter a master of water calligraphy. The complicated calligraphy of Chinese writing is comparable to an art, and calligraphic displays are very common here. But to see water calligraphy is something much rarer!

The basics are much the same. The artist takes a brush, makes a few breathing exercises, focuses, and thinks about what he will write (most of them are men). Then, he sets to work, trying to maintain the perfect rhythm. Instead of ink, however, the brush is tipped into pure water. And a few minutes after the writing is complete, it will vanish as if it was never there.

This concludes your tour of the magnificent Temple of Heaven complex, one of the true gems of Chinese architecture in Beijing, carrying so much history in it.

5. Hall of Prayer for Good Harvest

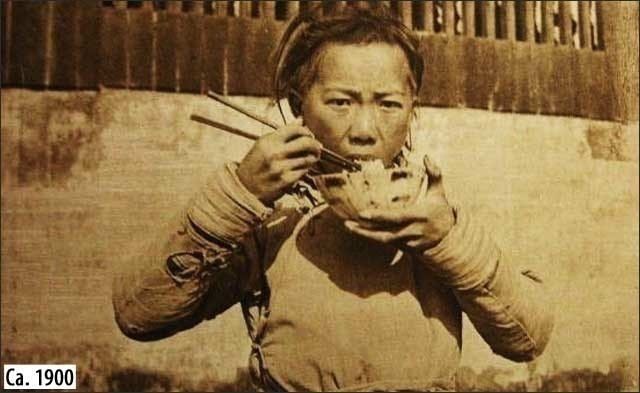

Chinese Cuisine

China is considered to have one of the most varied gastronomic cultures in the world. Many people compare it to France and Italy – the West’s most famous food producing nations.

It is often said that the Chinese will eat anything and everything: if it has four legs and isn’t a table, or it flies and isn’t an airplane, or it swims and isn’t a submarine – it will be cooked and consumed by someone.

This isn’t strictly true but it’s a great way to begin to appreciate the diversity of Chinese food. This diversity means that we need to simplify things a little in order for you to get a better understanding of food in this vast country.

Let’s start by breaking the country up into four parts. Some suggest that you can filter Chinese food just by a north-south divide, but we think there’s more complexity than that and we’d like to add an east-west dimension to things. There are eight schools of traditional cookery, which cover these regions.

The first and largest school is from Beijing. The Lu or Shandong style of cookery is often considered to have two sub-classes of its own: Jiaodong (which originates in Fushan, Qiangdao, Yantai, etc.) – a light style of cuisine focused very much on fish; and Jinan (which originates in Jinan, Tai’an, Dezhou, etc.) – a simple style which uses a lot of soup in dishes.

When you travel in northern China this is the school you’ll most commonly come across and while you can find variants of Shandong cuisine throughout China the most authentic is found in the north.

What can you expect in Shandong cookery? Given the size of China, ingredients vary depending on their availability and even modern transport networks don’t always ensure the availability of everything, everywhere in the country.

Seafood is a key ingredient and every kind of edible catch makes an appearance.

The adventurous person might fancy sea cucumber (also known as sea slug), which some say is a textural delight while others are not so kind. Clams, abalone, scallops, all kinds of fish, prawns, shrimp, etc. are all likely to grace Shandong tables.

Corn is a unique factor in Shandong cookery, as it’s not widely produced in China. It is markedly different from American or Western corn and tends to be full of starch and quite chewy compared to the sweetness preferred by Western menus. It is often served on the side of meals as corn-on-the-cob, which might be prepared via steaming or boiling. It is also sometimes peeled off the cob and fried.

Then there are lots of peanuts, sometimes served in little bowls covered to excess with salt and sugar, other times they are added to the dishes themselves. The peanuts tend to be very sweet and have a delicate aroma that gives them a very broad appeal.

You’ll also be surprised to find that China’s largest school of cookery is not particularly dependent on rice. In fact, it is grain crops that make up the majority of carbohydrates in meals from the area. They can be milled and cooked into breads (steamed or fried) or added to congee or porridge for thickness and flavor.

Shandong cookery also relies on rather fewer vegetables than the other schools. You can find potato, mushroom, onion, garlic, eggplant, tomato, grass-like greens and peppers. The area has a particular reputation for cabbages, which have a delicate flavor and are particularly easy to cook with. In winter you’ll find that cabbage is a main part of the diet in northern China.

However, where Shandong cuisine really comes into its own is in the use of vinegar. The area is famous for its abilities in the preparation of vinegar. The local preference is for rich, complex flavors. Shandong vinegar is valued by people who really enjoy their Chinese vinegar.

Things to watch out for (for the nervous eater) include fried pig intestines, deep fried locusts, and all manner of stir-fried offal – brains, hearts, livers, feet, etc., the bits of the animal that we generally don’t eat in the West. Shandong food is hearty stuff designed to support the body in all weathers and at all times of the year.

This isn’t the only food culture in northern China mind you – there’s also Xinjiang food, which is heavily accented to Muslim diets and remains very distinct from Shandong food. If you’re lucky enough to eat in a restaurant focusing on this food you should concentrate your efforts on the mutton or lamb for which the region is famous. You won’t find too much pork on the menu but unlike in other Muslim areas of the world, you can usually get a beer without too much trouble.

Next up is the Yue school of cookery, which originates from the southern tip of China and is often called Cantonese by those who are used to eating this in their home countries. It is one of the most inventive styles of Chinese foods because of the addition of many imported ingredients. Guangdong province’s ports have always been essential for trade in China, and unlike most of the rest of the country, there’s been plenty of opportunity to add a little overseas flavor to dishes.

Cantonese cookery uses a wide range of meats though lamb and goat aren’t usually found on the menu, mainly because there’s not much lamb or goat farmed in the Guangdong area. You may be lucky enough to find snakes, snails and duck’s tongues to make up for that though. While there is a reliance on steaming and stir-frying, cooks also braise, shallow fry, double steam and deep-fry their offerings.

The British royal, Prince Philip, was once widely criticized in the Western press for saying: “If it has four legs and isn’t a chair, if it has two wings and isn’t an airplane, or if it swims and isn’t a submarine – the Cantonese will eat it.” However, this is a common Chinese phrase and is used widely around the country with no insult meant.

The flavor of Cantonese food tends to draw on simple seasonings like sugar, salt, soy, rice wine, vinegar, spring onion, etc. and in general spices are kept to a subtle minimum. Hoisin and plum sauces originate from this area as does black bean sauce, sweet and sour, char siu and more. Freshness is of course important to the Cantonese chef but there’s also an abundance of dried and preserved ingredients employed in the school: fermented tofu, dried cabbage, salt pork, etc. can all be used to give additional variation to a meal.

Most Cantonese meals are served with simple accompaniments of plain white rice to soak up the complex flavored sauces used for the main courses.

Dim sum is particularly popular in the region and tends to be served in small bite-sized portions in order to add a staggering level of variety to any occasion. It is traditionally served in small steamer baskets or on small plates.

Eating dim sum at a restaurant is usually known in Cantonese as going to “drink tea,” as tea is typically served with dim sum.

The huge number of popular dishes in Cantonese cookery makes it impossible to list them all. It’s perhaps the easiest region in which to taste those firm favorites of the Anglicized Chinese cookery of the West in their traditional form.

Let’s now head west to Sichuan for the other well-known form of Chinese cookery in America and Europe. This school is most commonly spelled Szechuan but the pinyin rendition is more correctly Sichuan.

Sichuan food is famous for being hot and spicy but there’s enormous variation in regional cooking and while pepper is a very common ingredient, the school focuses on combining seven basic flavors: sour, hot, aromatic, salty, sweet, bitter, and pungent or strong smelling. It’s this drive for balance that has made the school very popular in the U.S.

The key ingredient is the Sichuan pepper which is an extremely fragrant pepper with a citrusy flavor that numbs the mouth in a way reminiscent of chili peppers. Star anise, chili, ginger, and garlic are also extremely common ingredients. The most common meat used is beef mainly because oxen are farmed locally.

The techniques used to make Sichuan food are extremely diverse and there are over twenty used throughout the region; the most common are braising, stir frying and steaming.

The best-known dish from Sichuan is probably Kung Pao chicken.

The Sichuan hotpot is a huge crowd pleaser and unlike hotpots elsewhere in China the bowl is usually split into two sections of broth: a very spicy broth and a plain broth.

Tea smoked duck is a firm favorite of those who prefer their food a little less fiery.

The next highly influential school of Chinese cuisine is Jiangsu from eastern China. In Jiangsu cookery there is a focus on presentation and texture. Foods are often chosen for their different colors to complement each other on the dish. Different shapes are used to heighten the visual appeal too. In addition, meat tends to be slow cooked in order to leave it extremely tender, it doesn’t quite fall off the bone but it isn’t far off either. Soups are a common feature of Jiangsu cookery.

Like with all the major schools there are several sub-sections of Jiangsu cookery and you cannot rely on the same food all over the region. Nanjing food for example tends to use duck and shrimp, whereas Suzhou prefers strong tasting and sweet dishes, and Wuxi relies on local freshwater products as the main ingredients for cooking.

Westerners tend to enjoy the braised spare ribs, which are a specialty of the region. Fried gluten balls are often stuffed with meat for taste or stir-fried as an accompaniment to vegetables.

There are then four other significant schools of cookery that make up the eight best known in China.

The first on this list is Hunan, an area famed for its blindingly hot and spicy dishes. Where Sichuan food is considered to have a numbing heat, Hunan heat is not so generous to the mouth of the eater. It contains a lot more chili and uses dried as well as fresh peppers of all varieties. Hunan food tends to incorporate rather more dried, smoked and cured goods than any other form of Chinese cooking.

There is also a significant amount of seasonal variation and during the long, hot summers meals may be served cold and in the winter there’s a definite preference for hot pots, which may, like those in Sichuan, be split into spicy and non-spicy sides.

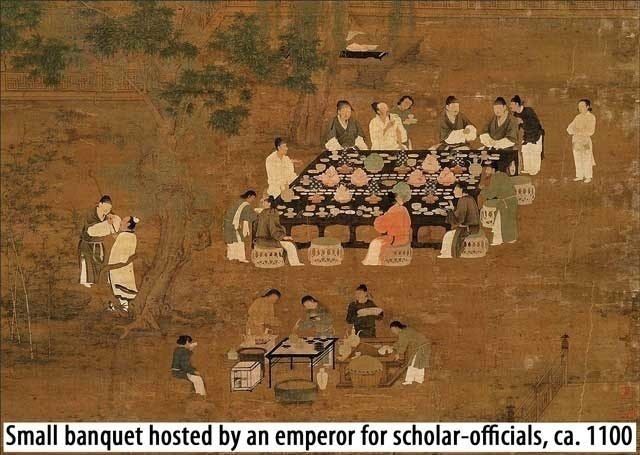

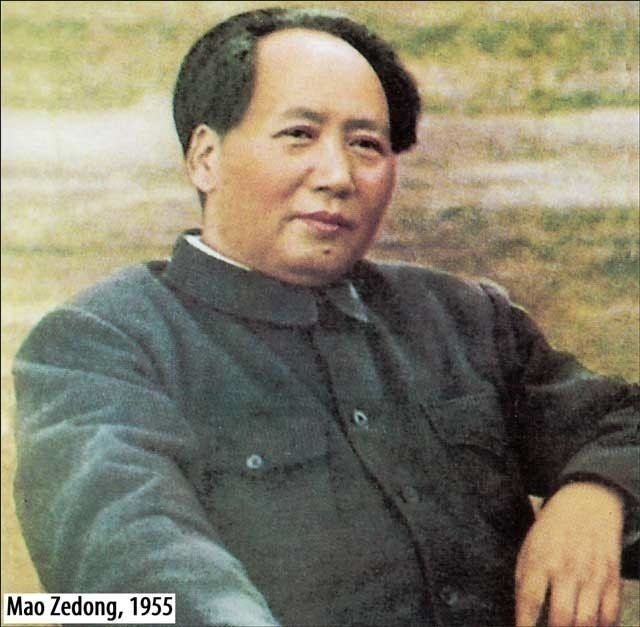

The most famous dish from the region is perhaps Mao’s braised pork, which can be very fatty but is absolutely delicious. It became named after Mao Zedong, the founding father of the People’s Republic of China, who loved the dish.

Other famous Hunan dishes are: beer duck, “dry-wok” chicken, mala chicken, and lotus seeds in rock sugar syrup.

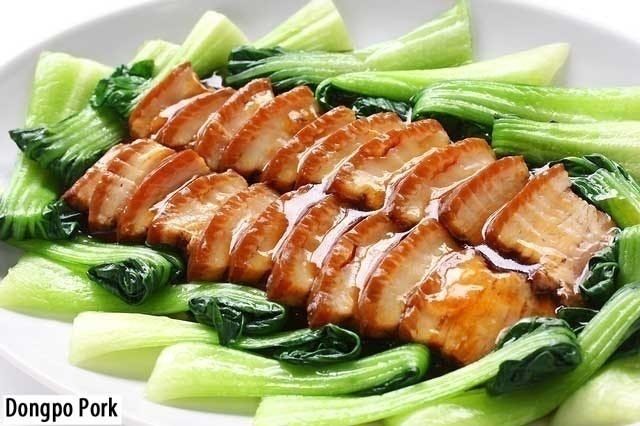

Then, there is Zhejiang food, which by contrast is much less oily than any other style of food in China and tends to be delicately fragranced. There are several sub-styles of Zhejiang food though all tend to emphasize freshness.

Dongpo pork is perhaps the most popular Zhejiang dish and can be found throughout the country. This is first pan-fried and then red cooked pork belly, consisting of half fat and half lean meat, which has been marinated in soy sauce and rice wine. Red cooking, also called Chinese stewing, is a slow braising Chinese cooking technique that imparts a red color to the prepared food.

The dish is named after the famed Song dynasty poet Su Dongpo (also known as Su Shi) who lived during the 11th century. Legend has it that while Su Dongpo was banished to Hangzhou, to live a life of poverty, he made an improvement of the traditional process of frying pork belly. He first braised the pork, then added Chinese fermented wine and slowly stewed it on a low heat. The story runs that once during his free time, Su Dongpo decided to make stewed pork. Then an old friend visited him in the middle of the cooking and challenged him to a game of Chinese chess. Su Dongpo had totally forgotten the stew until a very fragrant smell reminded him of it.

Then, there is the Fujian’s school of cookery delivering meals which are light but packed with taste, with delicate textures and an emphasis on the taste known as umami, which is a Japanese word and is the name of one of the five key tastes our tongues can distinguish. It means “pleasant savory taste” which doesn’t really give much away as to how it differs from other tastes. It is picked up on the tongue through L-Glutamate receptors. It’s been shown in the lab that it is possible for dishes heavy in umami to compensate for a lack of salt.

Ingredients in Fujian cookery are extremely diverse with mushrooms, seafood, bamboo shoots and even turtles making a regular appearance on the dining table. Braising, stewing, steaming and boiling tend to be the preferred methods of preparation. Broths quite often make up the base of any meal and it is considered poor form for a meal to come without soup. There is also a real preference for fermented fish oils and peanuts in this kind of food.

Fujian cuisine tends to be less well known outside of China and the chance to try this food shouldn’t be missed. The most famous dish is “Buddha Jumps over the Wall” made of duck, scallops, shark’s fin, abalone, sea slug, pig’s feet, pigeon’s eggs and more. It’s named after a folk tale of a monk who gave up his vow of abstinence because the smell of the dish was so appealing he leapt over the wall of the monastery to try it. Ban Mian, an egg soup, is also very popular.

Last but not least there’s Anhui cuisine, which is said to have originated in the Huangshan Mountains. It bears a certain similarity to Jiangsu cookery and tends to use braising and stewing as the preferred preparation methods. Wild herbs are key ingredients and flavors tend to be complex and satisfying. The Li Hongzhang Hodge-Podge uses a whole host of ingredients including sea slug, fish, squid, bean curd, pork, chicken and vegetables. The Luzhou roast duck rivals its more famous cousin Peking duck for the title of best duck dish in China.

Throughout China and all the schools of cookery there is an underlying belief that food has healing properties.

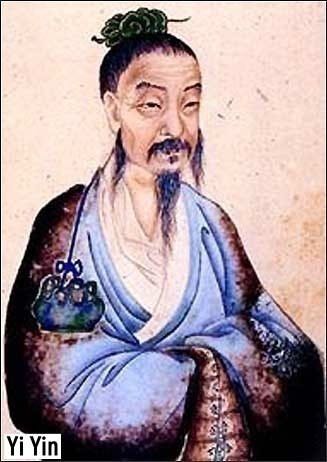

Yi Yin, a scholar from the Shang dynasty, who lived during the 16th century B.C.E., proposed that foods can be harmonized to provide benefits to health. He identified five separate flavors and related these to specific areas of the major organ systems. Thus sweet benefits the heart, sour the liver, bitter the spleen, piquant the lungs and salt the kidneys.

This belief spread quickly and many Chinese ingredients in dishes also play an important role in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). Scallions, ginger, garlic, fungi, etc. are all attributed with the ability to prevent certain illnesses and thus are ideal for heavy use in many areas of the country where they are found naturally.

Meals are supposed to be balanced by their constituent components too, so a meat dish should always have at least a third of the dish given over to vegetable content and vice-versa. The water used to prepare a soup should always be seven tenths of the volume of water needed to fill a serving bowl. These rules, while perhaps not delivering the precise health benefits attributed to them, certainly show an awareness of the need for a balanced diet and may explain why Chinese people can eat huge portions and remain thin.

It is worth noting that the main component of Chinese food almost everywhere is rice. According to a Chinese legend rice is the gift of animals to people. The legend tells that after a severe period of floods all plants had been destroyed. When the land had finally drained, people came down from the hills where they had taken refuge, only to discover that there was little to eat. One day a dog ran through the fields to the people with rice seeds hanging from its tail. The people planted the seeds, rice grew and hunger disappeared.

But white rice is not so healthy when eaten in excess. Whilst Chinese people are gradually getting fatter, in keeping with their Western counterparts, as their portion sizes increase and fast food becomes more popular; in general they are a thin people but with a very high rate of diabetes. This is currently thought to be because of the volumes of rice consumed.

As you can see, China has an extremely varied food culture. It’s a great place to eat and it is possible that China offers the greatest variety of food of any nation in the world.

And now, bon appetit! But there isn’t really an equivalent in Chinese – the literal translation would be ge bao but it’s more usual to say “qing man yong,” which means “please eat slowly.”

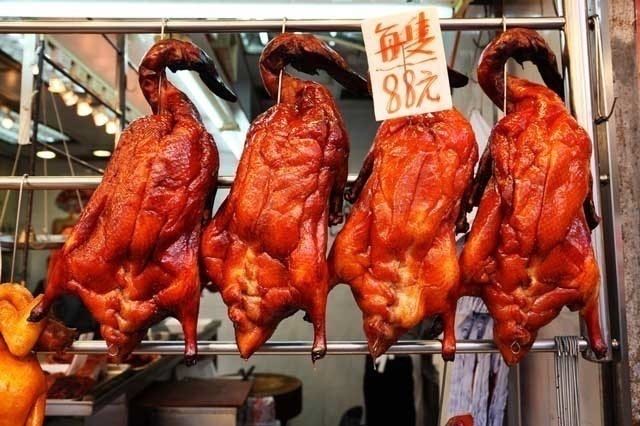

Peking duck, a famous duck dish from Beijing, has been prepared since the imperial era, and is now considered a national dish of China.

The cooked Peking duck is traditionally carved in front of the diners and served in three stages.

First, the skin is served dipped in sugar and garlic sauce.

The meat is then served with steamed pancakes, spring onions and sweet bean sauce.

Several vegetable dishes are provided to accompany the meat, typically cucumber sticks.

The diners spread sauce, and optionally sugar, over the pancake. The pancake is wrapped around the meat with the vegetables and eaten by hand.

The remaining fat, meat and bones may be made into a broth, served as is, or the meat chopped up and stir fried with sweet bean sauce. Otherwise, they are packed up to be taken home by the customers.

Duck has been roasted in China since the 5th century. It is known that a variation of roast duck was prepared for the emperors of the Yuan dynasty, as a dish, originally named Shaoyazi, was mentioned in the Complete Recipes for Dishes and Beverages in 1330 by an inspector of the imperial kitchen. The Peking duck was fully developed in the 14th and 15th centuries during the Ming dynasty, and was one of the main dishes on imperial court menus. The first restaurant specializing in Peking duck, Bianyifang, was established in Beijing in 1416.

By the 18th century the popularity of Peking duck had spread to the upper classes of China, inspiring poetry from poets and scholars who enjoyed the dish. For instance, one of the verses in “Duan Zhu Zhi Ci” was, “Fill your plates with roast duck and suckling pig.”

In 1864, the famous Quanjude Restaurant, specializing in Peking duck, was established in Beijing. The restaurant became well known in China, and introduced the Peking duck to the rest of the world.

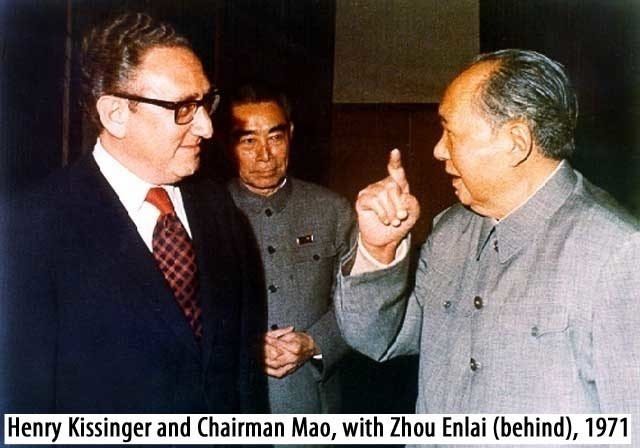

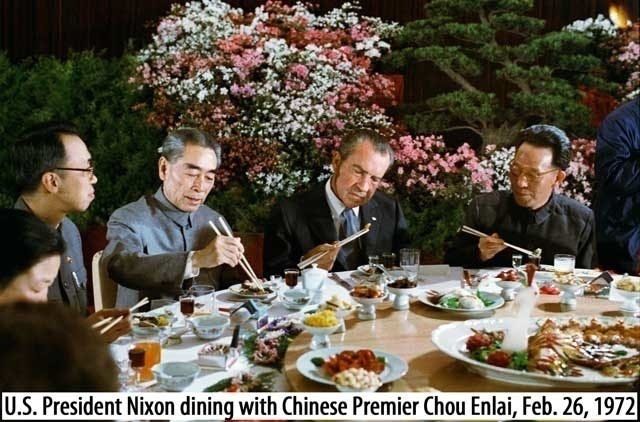

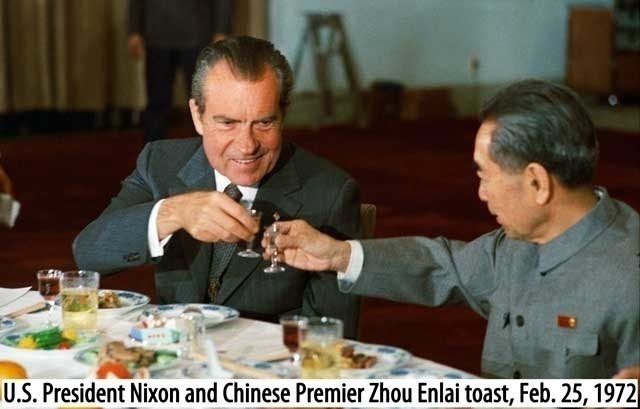

By the mid-20th century, Peking duck had become a national symbol of China, favored by tourists and diplomats alike. For example, Henry Kissinger, the Secretary of State of the U.S., met Prime Minister Zhou Enlai in the Great Hall of the People during his visit to China in 1971. After a round of talks in the morning, the delegation was served Peking duck for lunch, which became Kissinger’s favorite. The Americans and Chinese issued a joint statement the following day, inviting President Richard Nixon to visit China in 1972. Peking duck has hence been considered one of the factors behind the rapprochement of the U.S. to China in the 1970s.

Peking duck has also been a favorite dish for various political leaders ranging from Cuban revolutionary Fidel Castro to former German chancellor Helmut Kohl.

Peking duck is prepared from the Pekin duck (Anas platyrhynchos domestica). Newborn ducks are raised in a free range environment for the first 45 days of their lives, and force fed four times a day for the next 15-20 days, resulting in ducks that weigh five-seven kilograms (11-15 pounds). The force feeding of the ducks has led to an alternate name for the dish, Peking stuffed duck.

Fattened ducks are slaughtered, plucked, eviscerated and rinsed thoroughly with water. Air is pumped under the skin through the neck cavity to separate the skin from the fat. The duck is then soaked in boiling water for a short while before it is hung up to dry. While it is hung, the duck is glazed with a layer of maltose syrup, and the inside is rinsed once more with water. Having been left to stand for 24 hours, the duck is roasted in an oven until it turns shiny brown.

Peking duck is traditionally roasted in either a closed oven or hung oven. The closed oven is built of brick and fitted with metal griddles. The oven is preheated by burning Gaoliang sorghum straw at the base. The duck is placed in the oven immediately after the fire burns out, allowing the meat to be slowly cooked through the convection of heat within the oven.

The hung oven was developed in the imperial kitchens during the Qing dynasty and adopted by the Quanjude Restaurant. It is designed to roast up to 20 ducks at the same time with an open fire fueled by hardwood from peach or pear trees. The ducks are hung on hooks above the fire and roasted at a temperature of 270°C (525°F) for 30-40 minutes. While the ducks are cooking, the chef may use a pole to dangle each duck closer to the fire for 30 second intervals.

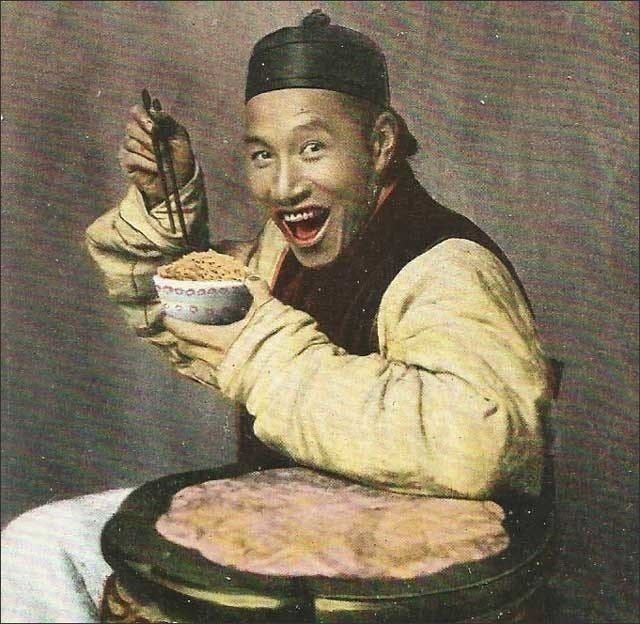

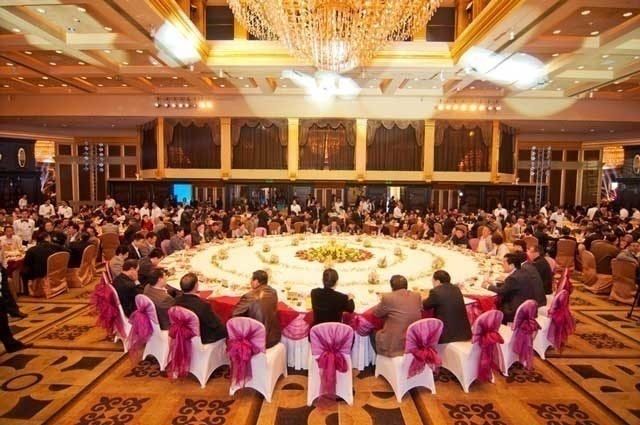

Eating out in China is very much a social occasion. Meals are for sharing and the idea is to try and get as many different dishes as possible. Entertaining is often done for reasons of “face” and to try and curry favor with guests in the form of guanxi. That means many Chinese meals appear to be extremely wasteful by Western standards.

Huge volumes of food are ordered to impress the others at the table and there is no expectation that everything will be eaten by the end of the meal. In some cases the meal may be barely touched if discussion is particularly lively.

Food is usually served with communal serving chopsticks, or more recently large spoons have also been making an appearance at the table. These should be used in preference to using your own chopsticks or rice spoon.

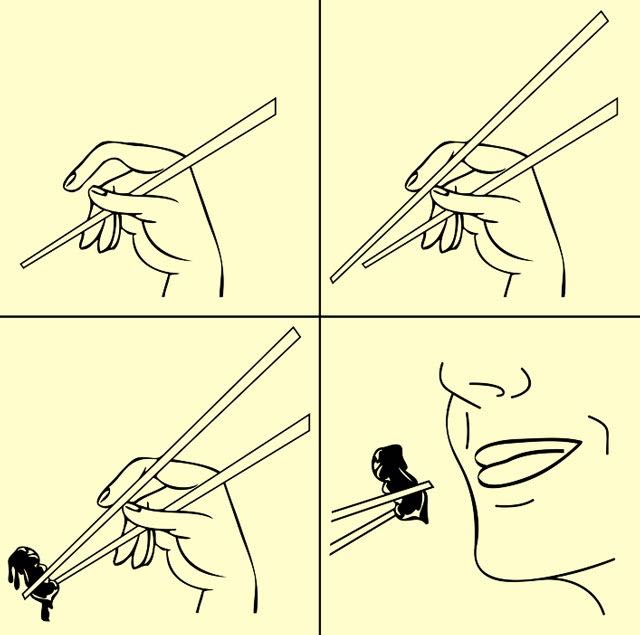

Chopsticks originated in ancient China as early as around 1200 B.C.E. and at first were supposed to be used for cooking, stirring the fire, serving or seizing bits of food. Chopsticks began to be used as eating utensils probably from around 200 B.C.E.

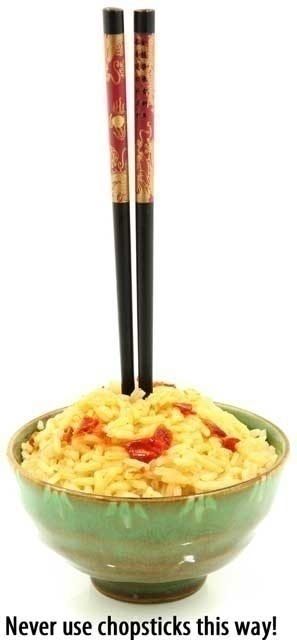

There is a general code of chopstick etiquette that you should be aware of. It is possible to deeply offend a Chinese host through the misuse of chopsticks. So let’s run through some of the more important rules.

Chopsticks should be left evenly on your plate and there should be no overlap between them. The shape of uneven chopsticks is considered to be extremely similar to that of a Chinese coffin. Nobody likes to be reminded of death at the dinner table, do they?

Using chopsticks for the first time can make you feel a bit like a kid learning to use a knife and fork again. You should use your thumb and your forefinger to secure them and then place your other fingers against the sides to keep them under control.

Don’t, whatever you do, stick your forefinger up and point it at others around the table. This is how children are disciplined in China. It’s also very rude to point at someone with your chopsticks themselves.

It is absolutely essential that you do not leave your chopsticks pushed into your dish. This is the equivalent of sticking your middle finger up at someone in the West and is seriously, seriously rude. Once you’ve finished eating for a moment, it’s polite to put the chopsticks down on the plate or chopsticks holder.

You shouldn’t pass rice with the serving chopsticks in the rice. Instead pass the plate and then pass the chopsticks separately. It is said that chopsticks in rice looks like the sticks of incense burned during funerals in China. That death taboo is a strong one and best not invoked.

It is very rude to cross your chopsticks over when they’re on the plate. It’s a specific behavior used to tell someone else you think they’re full of nonsense when they’re talking. You’d probably be upset if someone told you that at dinner too.

Banging chopsticks against the bowl for attention is also a no-no. That’s because beggars bang their fingers against their bowls to get attention. It might seem like a small thing but it really is quite offensive to any Chinese dining companions you may have.

It’s worth pointing out that chopsticks belong on the table and not on the floor. It’s very rude to throw chopsticks on the floor and even if you drop them accidentally you should immediately apologize to your fellow diners. It’s thought that anyone’s ancestor spirits that are following the meal will be offended by falling chopsticks and take it out on those present.

Seating at a Chinese table is governed by order of importance at business dinners and even at less formal occasions. It’s best to let others show you where you’re expected to position yourself than rush in and upset the hierarchy. If there is a guest of honor at a meal the whole group will stand until that guest is seated. The guest of honor is the person who decides when you will start eating too. There is also a principle that you leave the best food for that person. Thankfully, the “best bits” are usually those considered inedible by Westerners such as fish heads and eyeballs.

Napkins aren’t normally placed directly into the lap – you put one end under your plate and then drape the rest over your lap. If you take a napkin, it’s considered very polite to offer the people around you one too.

You shouldn’t handle food directly during the course of a meal unless your fellow diners are. This can make for awkward moments of chasing a single peanut round with chopsticks but your efforts will be appreciated. This is also true for meat whether or not it is on the bone. In this situation large bones should be held with chopsticks as you eat the meat off the bone. In the case of small bones you are expected to put the whole thing in your mouth, pull of the meat and then spit the bones into a bowl or onto a plate. If you need to guide the bones to the plate – use chopsticks and not your fingers.

If there is a Lazy Susan, a round piece of glass that can be turned, on the table, then it should be rotated clockwise. It’s important to remember that the guest of honor gets first pick from every dish before you try something.

In general it’s not polite to refuse a taste of a dish. It’s better just to take something and then leave it on the edge of your plate if you don’t want to try it.

If you need to use a toothpick, cover your mouth with the other hand when you use it. Toothpicks should also be placed on your plate and not just left on the table and they should never ever be thrown on the floor in any circumstances.

Tea accompanies all Chinese meals. But beer has also become quite popular along with fruit juice for ladies.

Drinking at meals can be extremely overwhelming for Westerners. If strong alcohol is served you may be expected to drink a toast separately with everyone at the table.

This is usually in the form of gan bei (literally “finish glass”) and you will be expected to knock glasses and then drink the entire contents of the glass. Be warned, Chinese Baijiu is an extremely strong alcoholic beverage (40-60% alcohol by volume) and once the toasts start, you can’t get out of them. It is bad form to refuse a toast.

However, smart Westerners will know that the one thing the Chinese respect more than their cultural traditions is medical advice. Producing a pack of antibiotics and claiming that your doctor has insisted you do not drink will get you out of the round but obviously you can’t use this excuse every time you go out with Chinese friends.

At the end of the dinner when the bill comes it’s vital to ensure that the person doing the inviting for the meal gets to pay. You should make some show of offering to pay the bill but it’s absolutely not expected that you win the mock-fight to do so. If you don’t fight it shows that you think the meal is your right as a debt that the host has to pay to you. In these circumstances the bill is never split and it’s quite rude to offer to do so.

With colleagues or friends it may be acceptable to split a bill but it’s more common to take it in turns. So if you pay this time, they will pay next time. This may be applied more broadly than to just meals and for example you might pay for a meal one night and the next night your colleague might return the favor by paying for cinema tickets.

One other area of Chinese food culture of great importance is that of tea drinking. The Chinese have a very different tea drinking culture from other nations, and while tea drinking is not as an elaborate a ritual as you might find in Japan, it is still very significant.

Tea is deeply woven into the history and culture of China. The beverage is considered one of the traditional seven necessities of Chinese life, along with firewood, rice, oil, salt, soy sauce and vinegar.

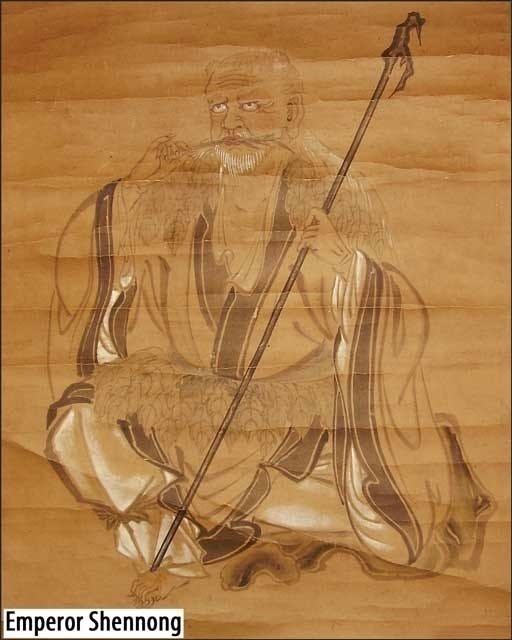

According to legend, tea was first discovered by the Chinese Emperor Shennong some 5,000 years ago. It is said that the emperor liked his drinking water boiled before he drank it so it would be clean, and that is what his servants did. One day, on a trip to a distant region, he and his army stopped to rest. A servant began boiling water for him to drink, and a dead leaf from a wild tea bush fell into the water. It turned a brownish color, but it was unnoticed and presented to the emperor. The emperor drank it and found it very refreshing, and tea came into being.

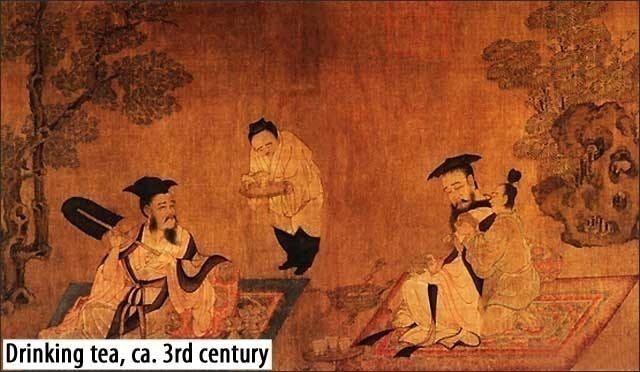

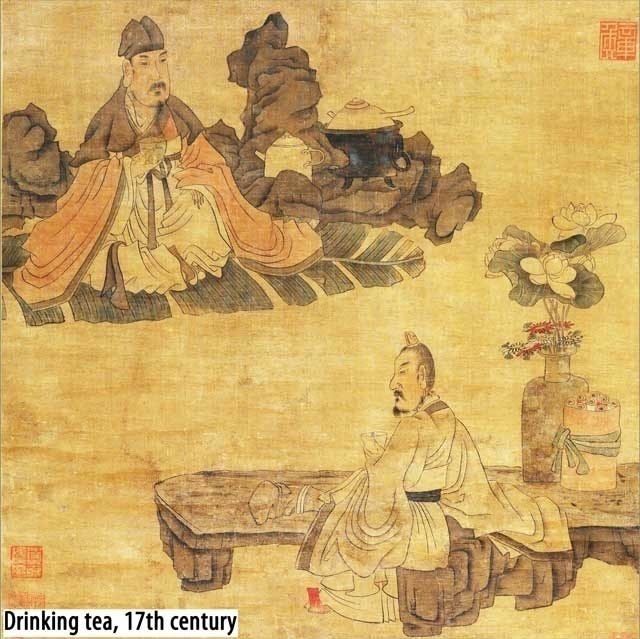

During the earlier Southern and Northern dynasties (420-589), and perhaps even earlier, the drinking of tea became popular in southern China. During the Tang dynasty (618-907), tea became synonymous with everything sophisticated in society.

The 8th century author Lu Yu, known as the Sage of Tea even wrote a book called Classic of Tea, which includes four parts: Origin, Tools, Making, and Utensils.

Tea is consumed regularly at almost every occasion in China. It will normally be served in business meetings as well as at meals, informal get-togethers, etc. It also has a part to play in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM).

Tea in China is normally called cha and the term refers to drinks made from Camellia sinensis (the modern tea plant).

There have been times in Chinese history when tea was considered to be any bitter drink made from a plant, but today this interpretation has fallen out of favor.

Tea is prepared and consumed for a whole host of reasons but there are some common reasons.

For instance, inviting someone from the older generation to join you for a cup of tea is considered a mark of respect. In these instances the lowest socially ranked person is expected to pour the tea. This might be children treating their parents or an underling currying favor with their boss. However, in some occasions where the low ranked person has achieved something memorable, like good exam results or record sales volumes, the higher ranked person may pour for the lower.

Tea drinking is an important part of general family gatherings. It’s not unusual for a family to join each other just to sit together, talk, and drink tea in a restaurant.

One area that you hope not to have to become familiar with is drinking tea to apologize for serious misdeeds. If you hurt someone’s feelings or caused them to lose face, a good step towards mending fences with them is to take them for tea and to pour the tea by way of apology.

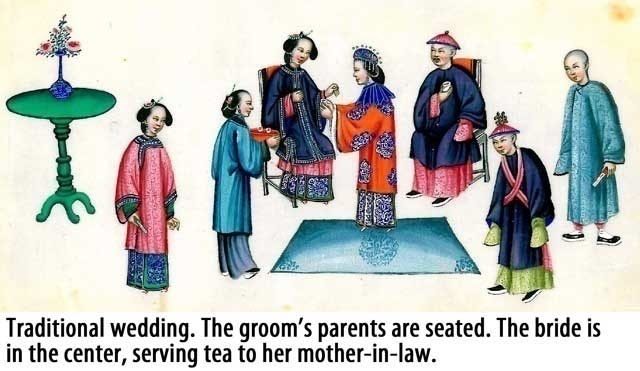

During the traditional marriage ceremony it’s not uncommon for the bride and groom to kneel on the ground in front of their parents and then pour tea for them. This is to express their gratitude for their upbringing. Sometimes it is only the bride who pours tea for the groom’s family to show she is grateful for the chance to become a part of their family. It is also quite common for large families at weddings to separate into groups and serve each other tea as a bonding ritual designed to bring the two families closer together.

If someone pours tea for you it is customary to thank them for doing so. “Xie xie” is how you say “thank you” in Chinese. If however, it is not possible to say thank you (for example you’re deep in conversation) it is customary to symbolize this by tapping your fingers, index and middle, against the cup or the table.

Most of the ceremony in a Chinese tea ceremony is reserved for the brewing of the tea. The right teas must be selected, delicate green teas or heavier black teas, and then brewed to perfection.

There are two main methods of brewing tea.

The Chaou style involves placing the tea in a bowl and then adding hot water. The bowl comes with a cover and a saucer. The cover is left on while the tea brews and then removed for drinking.

There is also the Gonfu Chadao approach, which is more formal and the tea is brewed in a teapot to give a more rounded balanced flavor to the final brew.

The brewing ceremony may be quite ornate in terms of the selections of leaf and the way that the tea is finally poured for guests.

If you are using a teapot, the lid should be kept in place during pouring to prevent it from falling off. You should never point the spout of the teapot at someone, this is extremely rude. You should hold the teapot in your right hand to pour and hold the lid with your left to represent honor and fidelity. It is polite to ask others if they would like more tea and serve them before refilling your own cup.

When the bowl or teapot gets empty, just more water is added instead of bringing a new bowl or pot. If you need more water for the pot then you place the pot near the edge of the table and leave the lid ajar, so a server can reach it without disrupting the conversation.

Travel guides that show you around and tell stories, not just history.

Dear Traveler, please review this book, we truly appreciate your feedback.

Are you exploring famous landmarks in cities around the world? Are you looking for more insight than a typical guidebook provides you? Perhaps you would like your own personal tour guide but prefer to visit places at your own pace? Are you curious about how people lived in those palaces and castles? Maybe you just want to understand people from different cultures better? Well, we have exactly what you need, we tell WanderStories™.

WanderStories™ is the best local guide for you, showing you around and telling stories of famous and interesting sights, in an e-book on your tablet, smartphone, or computer.

WanderStories™ travel guides are unique because our storytelling style puts you alongside the best local guide who tells you fascinating stories, while a wealth of high quality photos, historic pictures, and illustrations brings your tour vividly to life.

WanderStories™ travel guides are e-books that include lots of photos, maps, and illustrations and tell you the stories behind the history of the places you will visit, like the best personal tour guides would do. In fact, they do it so well that you can visit the most extraordinary places around the world without even leaving the comfort of your armchair. Wherever you are, you can experience the excitement of history being recreated around you as the story unfolds.

You will get to know how real people, emperors and sultans, concubines and eunuchs, slaves and executioners lived in the palaces you will visit; what gods the monks worshipped in these temples; how generals and soldiers, crusaders and gladiators fought and won…or died. You will learn about local traditions and customs, holidays and festivals, cuisine, even jokes.

Whether you’re at home, on your travels, or walking in the historic setting itself, WanderStories™ is the best personal, local guide on your tablet, smartphone, laptop, or computer.

We, at WanderStories™, are storytellers. Our mission is to be the best local guide that you would wish to have by your side when visiting the sights.

Our promise:

• when you visit a city with a WanderStories™ travel guide you will have the best local guide at your fingertips

• when you read a WanderStories™ travel guide in the comfort of your armchair you will feel as if you are actually visiting the best sights in the city with the best local guide

Please get WanderStories™ travel guides at: wanderstories.com