Please buy the Kindle, iPad/iPhone or PDF versions or this and previous issues of Armchair Travel Guide at: wanderstories.com/travel-magazine-buy

Please subscribe to Armchair Travel Guide (web version will always be FREE) at: wanderstories.com/travel-magazine

Here is your current issue of the WanderStories travel e-magazine Armchair Travel Guide.

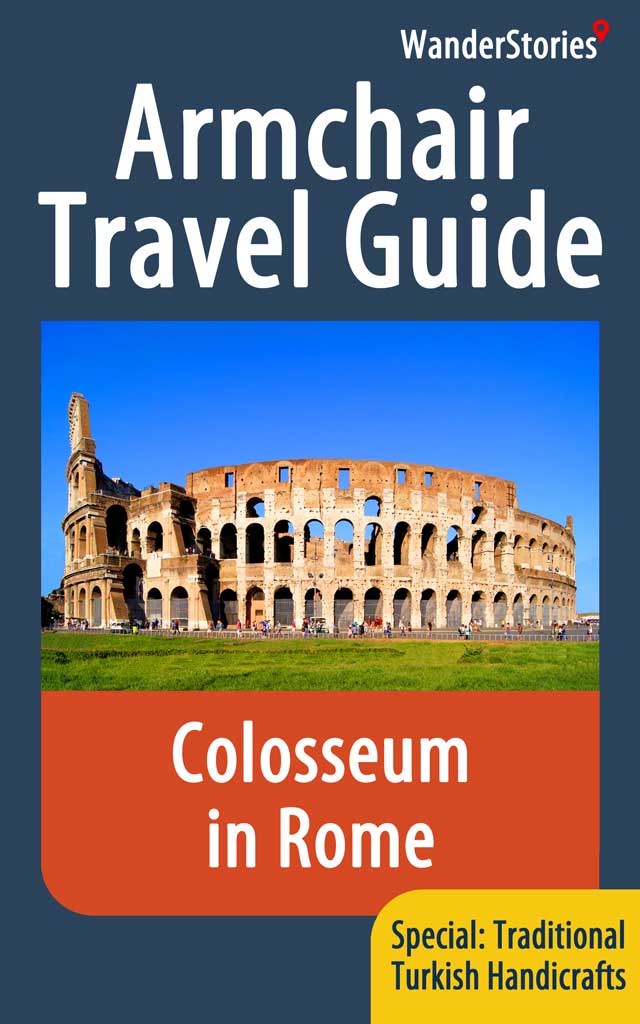

In the main story we take you to the WanderStories™ tour of the Colosseum in Rome, the largest amphitheatre in the world, visited by more than 4 million people every year.

In this issue’s special story you will get to know about Traditional Turkish handicrafts.

WanderStories™ is the best local guide for you, showing you around and telling stories of famous and interesting sights, in an e-book in your tablet, smartphone or computer. Our travel guides are unique because our storytelling style puts you alongside the best local guide who tells you fascinating stories, while a wealth of high quality photos brings your tour vividly to life.

Our promise: when you read this e-magazine in the comfort of your armchair you will feel as if you are actually visiting the Colosseum in Rome with the best local guide.

Let’s go,

Your WanderStories

Contents:

Traditional Turkish handicrafts

Address: Piazza del Colosseo

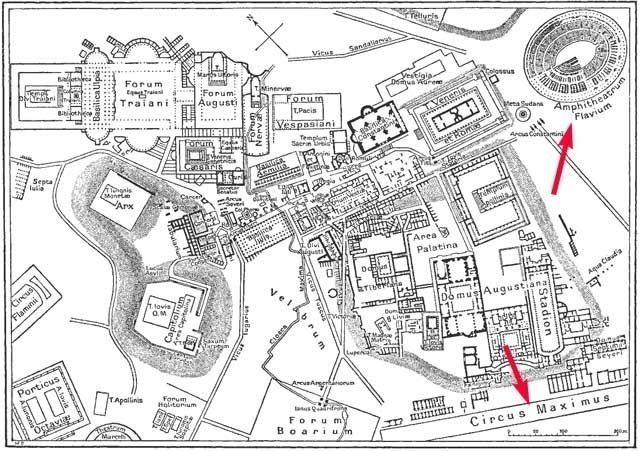

Surrounded to the east by the Roman Forum, and on the other sides, across the busy city traffic, by the Esquiline, Caelian and Palatine hills, the enormous arena of the Colosseum is the largest remaining symbol of Imperial Rome still in existence today.

Once a place for triumphs, games and executions the arena was a display of wealth and strength on a gigantic scale.

Today, the four-story structure is only a glimpse of its former glory. Although the marble facings, beautifully painted stucco walls and elegant statues have been taken to enhance other buildings throughout the city, enough of the original amphitheater still remains to help create an image of what it was like at the height of the Roman Empire.

The best view at the Colosseum is from the Via dei Fori Imperiali and the Piazza Venezia to the northwest. From here, you have the best perspective of scale with the four floors still visible.

Let’s walk around the outside past the Arch of Constantine, and enter via the main entrance in the west. This is the way the plebeians would have entered the grand Colosseum, lavishly decorated with statues of horses, eagles, which signified the power of Rome, and ancient gods such as Hercules, Apollo and Aesculapius.

They would enter through one of 76 entrances, the entrance number was indicated on their ticket; each doorway clearly numbered to allow thousands of people to enter in an orderly manner.

In Roman times, the tickets were known as tessara - small clay discs, which were stamped with details of the locus, or seat number, gradus or row number, cuneus, or sector and entrance gate. For example: LOC X, meaning seat number 10, GRAD V - row number 5, CVN III - sector number 3. Tickets were free, but everyone had to have a ticket to attend. Tickets were distributed to organizations, institutions and groups, who in turn, distributed them to the Roman citizens. As the games were popular, there was also a black market, where tickets would be sold, with high prices for some of the most important games.

There were also four other entrances. Two were for the gladiators - the Porta Sanivivaria or the Gate of Life, which led to their barracks and the Libitina, the Gate of Death, the gate where corpses and the defeated, badly injured, but still living, left the ground.

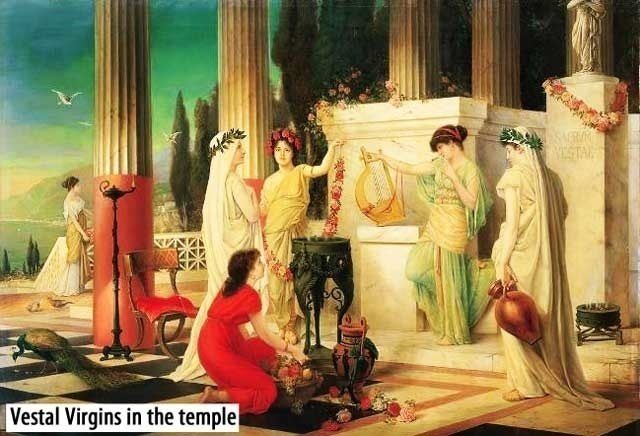

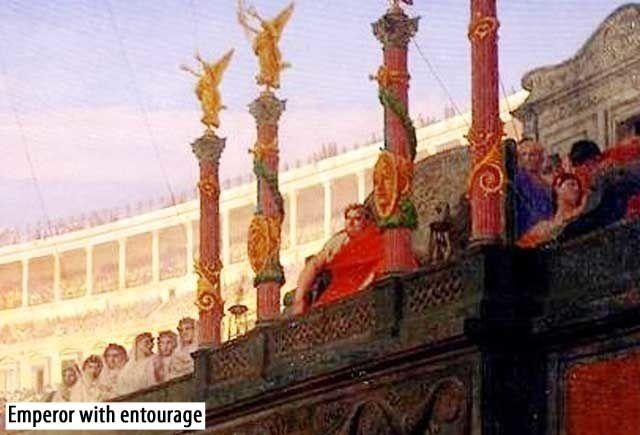

The other two entrances were for the emperor’s entourage, which included magistrates, the senate, priests and the Vestal Virgins.

The Vestal Virgins were six women, aged from six years old upwards, who served the goddess Vesta in a temple beside the Forum. They kept the fire of Vesta - the goddess of the hearth (fireplace), home and family, constantly burning in the temple. It was believed that if the fire went out Rome would fall.

The Vestals were also extremely powerful, they were able to free condemned prisoners or slaves by touching them, their words were unquestioned, and anyone threatening them harm would be killed.

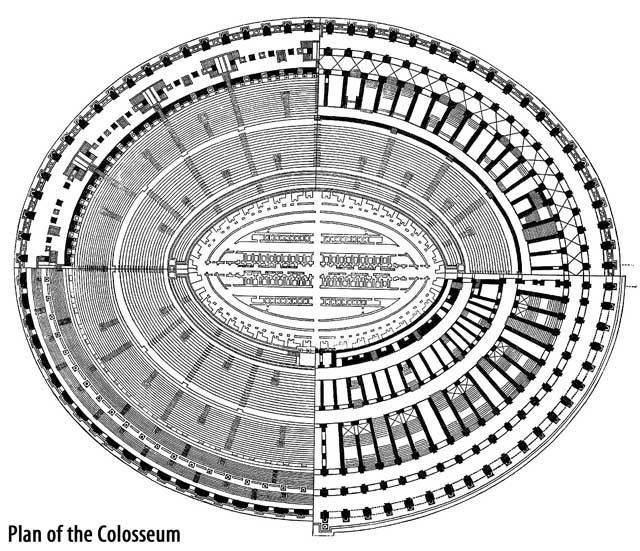

Roman kalendarium, or chronicles suggest that the amphitheater was able to seat 87,000 spectators, although today it’s suggested that seating for 50,000 is a more accurate figure.

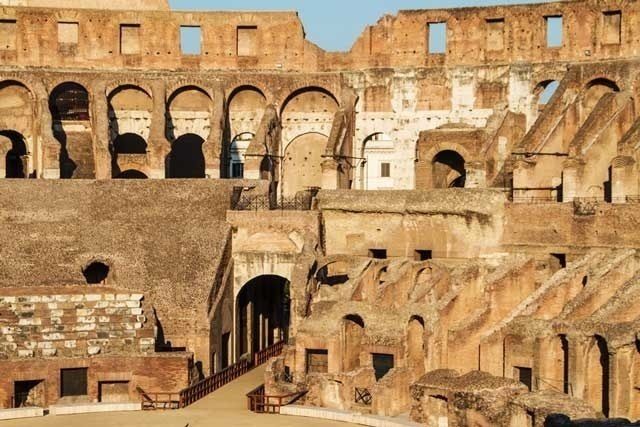

The amphitheater was constructed over four levels with arcades running around the perimeter; here there was access to the upper levels via steep stairways, and entrances to the seating area by 80 numbered passageways.

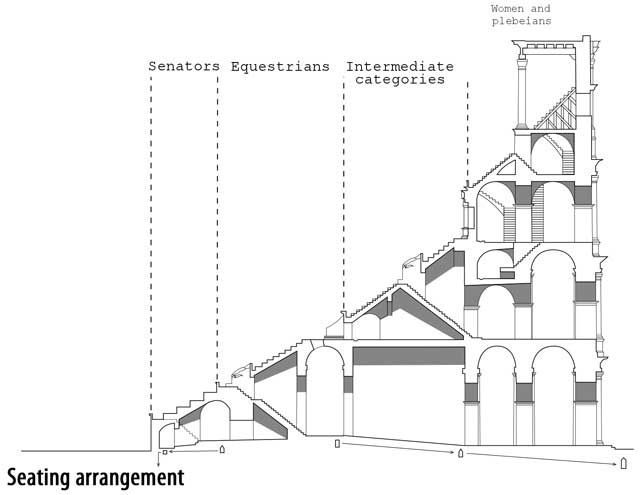

The four levels of seating had segregations for each of the different classes. The very highest was for women, the poor and slaves.

This level had square windows, some of which can still be seen today on the north side of the building.

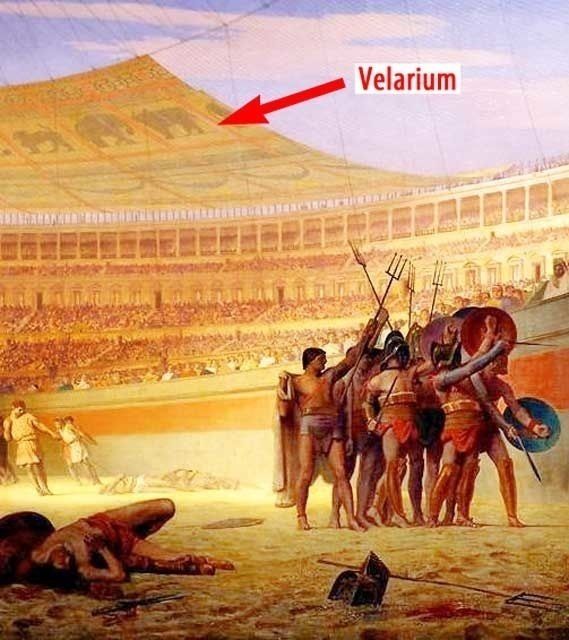

Above this floor, on the outside of the building, there were 240 brackets and sockets which anchored the velarium, or sail, onto wooden masts projecting out above the walls to create shade, or to provide protection from the rain. The sails were hoisted into place by strong sailors of the emperor’s fleet.

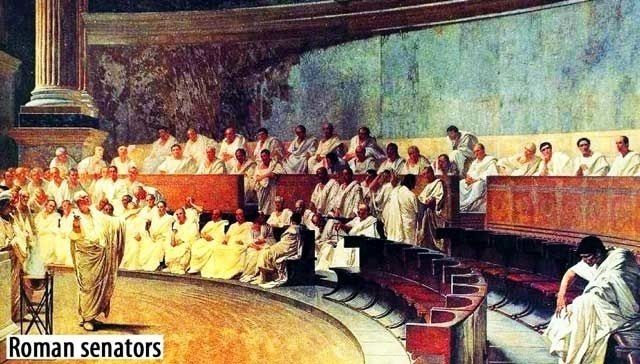

The third floor was for the plebeians or ordinary Roman citizens, the second floor was for the rich Romans with valuable property, and the first floor, next to the arena, was for the senators, the emperor and the Vestal Virgins.

Amongst these levels, there were also separate segregations. For example, on the second and third floors there were sections for boys who had not reached manhood and would sit with their tutors, another section for soldiers, and another for visiting foreign dignitaries.

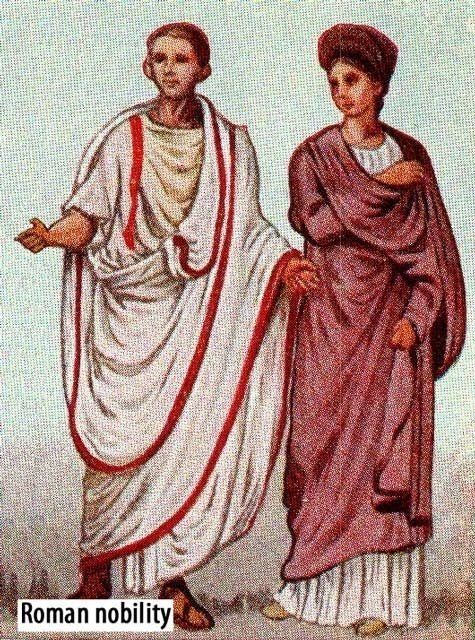

The emperor and the Vestal Virgins sat in boxes on the short, central axes to the north. The remainder of the area was where the senators, wearing their white togas edged with burgundy piping would sit.

Some would bring their own chairs and sit on wide, open platforms; others would sit in the middle section, which had built in marble seating. On these seats, there were inscriptions of the senator’s names who sat there; other parts had seat numbers.

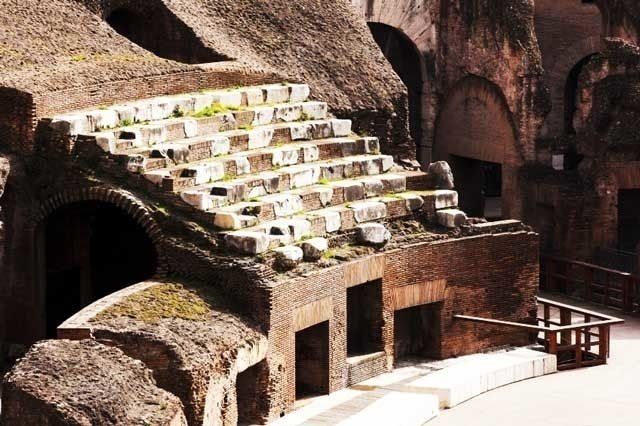

A small part of the seating area has been reconstructed above the covered section of the arena floor, and at the second floor, you will see pieces of stone taken from this central seating area.

Amongst these pieces of stone is one with the inscription “GRODIABLABI REGINIVC ETSP” and an almost heart-shaped symbol with a feather. This is the inscription and the demarcation sign of Senator Marcellus from the 6th century. The inscription and the demarcation sign carved into the stone acted almost like a seat number at a theater today, it would have been his seat.

But despite slaves and women being allowed to view the events, albeit from afar, there were a few sectors of society who were banned from visiting the Colosseum altogether: gravediggers, actors and anyone who had formally been a gladiator were amongst such people.

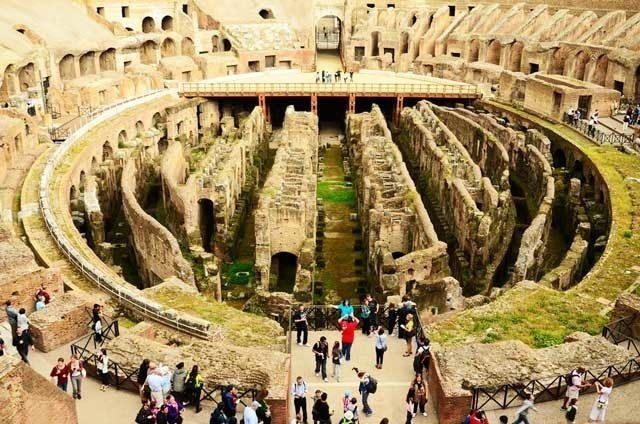

Today, the arena floor is open with its tunnels clearly visible, but in its Roman days, the series of 80 vertical shafts were covered with a hard wooden floor and trap doors, all hidden by a thick layer of sand.

Some of the shafts were used to bring stage effects, gladiators and animals in cages to just below the arena floor; other shafts were used to channel water into the arena.

The display on the second floor is also where you will find a number of stone weights, which were used along with a series of pulleys to open and close the trap doors, as well as detailed drawing of how the system worked.

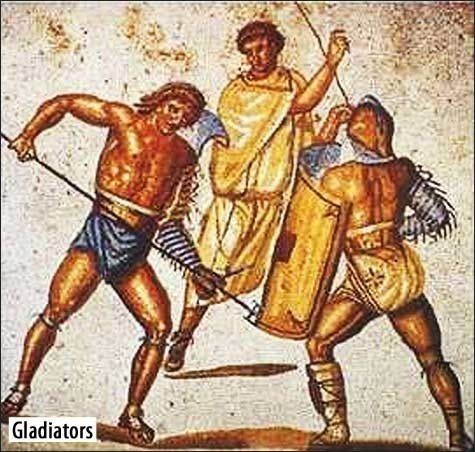

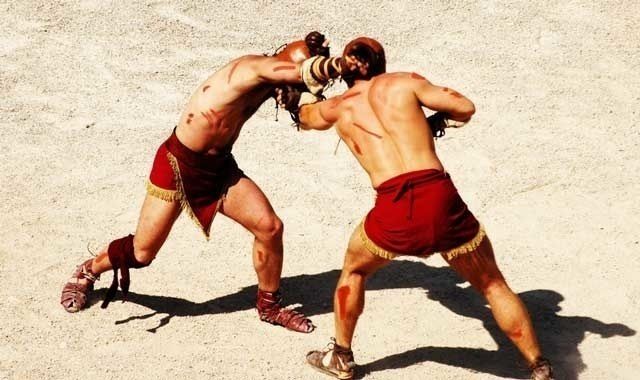

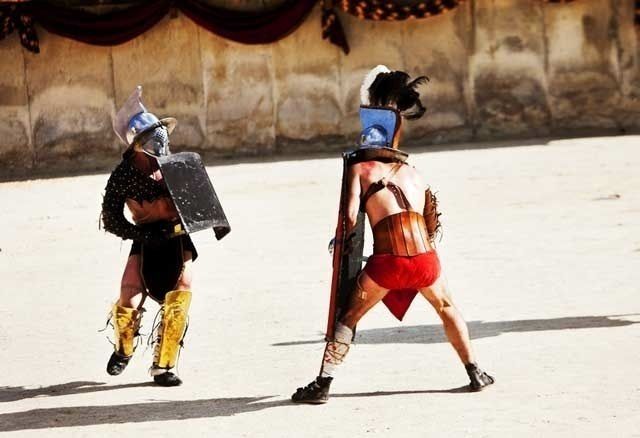

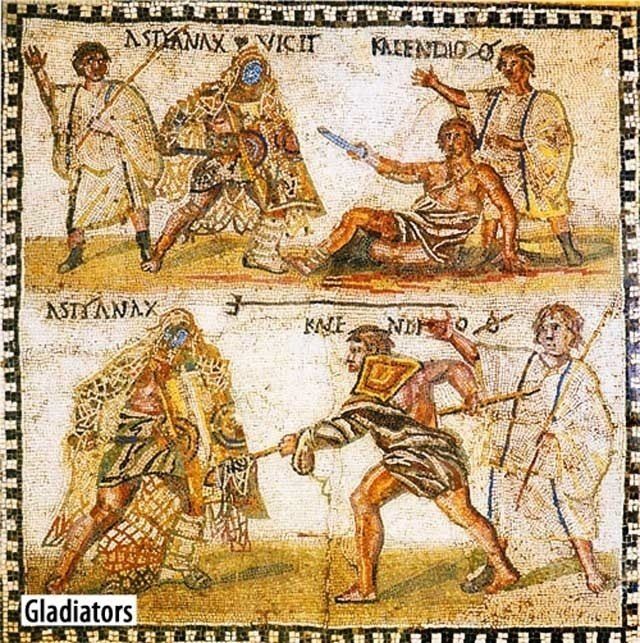

The most famous people of the Colosseum were, naturally, the gladiators. Usually, gladiators were condemned slaves or paid volunteers, schooled fighters who swore allegiance to a master and represented them in battle.

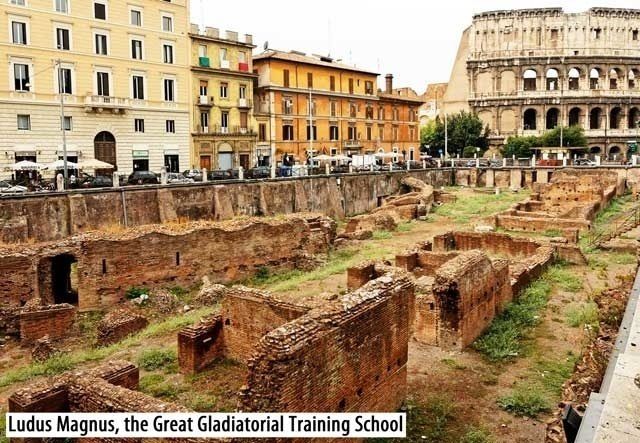

Gladiators went to gladiator school, a place to learn the techniques of how to fight and create a show. The Ludus Magnus, or the Great Gladiatorial Training School, was the largest of the gladiatorial schools in Rome. It was situated next to the Colosseum, and was connected to it by an underground gallery.

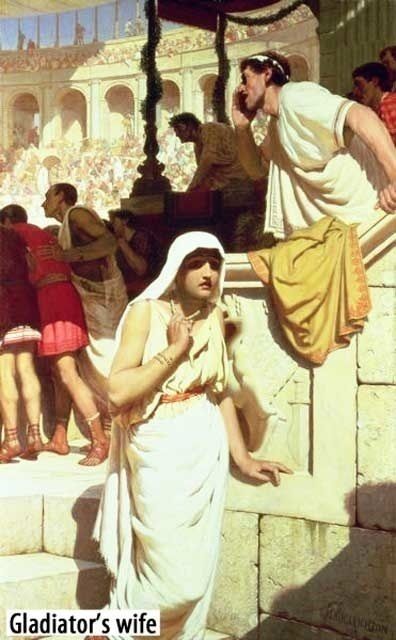

For the poor or for foreign citizens the opportunity to learn a trade, to eat regularly and to have somewhere to sleep was a compelling enough reason to become a gladiator. But for paid volunteers the initiative was, in the most part, the promise of fame and fortune. If they were as successful as they hoped, the winners would become rich and adored by the public, they would be showered with gifts and prize money, women would faint, overcome with emotion and desire for such a strong, brave man at their feet.

Although some Roman men disliked the gladiators, perhaps because they were seen to be strong and be able to attract women, they also secretly admired them. It was thought that the gladiator’s blood had special healing powers and that any man who drank it would receive greater sexual vigor, just like modern day Viagra. That made the gladiator’s blood both expensive and much sought after. It was also sought after in other way too as it was said by some to heal epilepsy.

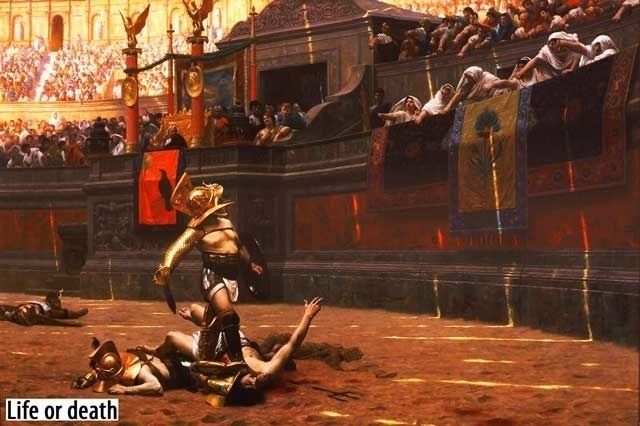

However, very few of the gladiators reached divine status, and for most, there was an extremely high probability that their lives would be cut short; the average gladiator only lived to be 30 years of age. Some combats would be a fight to the death, whilst others would be a matter of fate. The decision of whether a gladiator lived or died in these cases would be up the emperor, or the crowd. Those who were seen to fight well were often, but not always, spared. If a gladiator wanted to admit defeat, he did so by a rising a hand and then it was the emperor and the crowd who would determine his outcome.

Gladiators were trained never to ask for forgiveness, never to cry out, and to accept death with dignity. Suffering a ‘dignified death’ ensured that the gladiator’s soul was saved from sin and he was not branded as dishonorable or weak. To cry out was an absolute disgrace.

For those who died well, their departure from the arena was graceful, and once in the morgue, their armor would be removed, and their throat cut, just to make sure that they were dead. They also received an expensive cremation with offerings. On the other hand, gladiators who disgraced themselves were dragged from the arena either before, or after, being hit on the head with a large wooden club or hammer and their body dumped in the river or on wasteland.

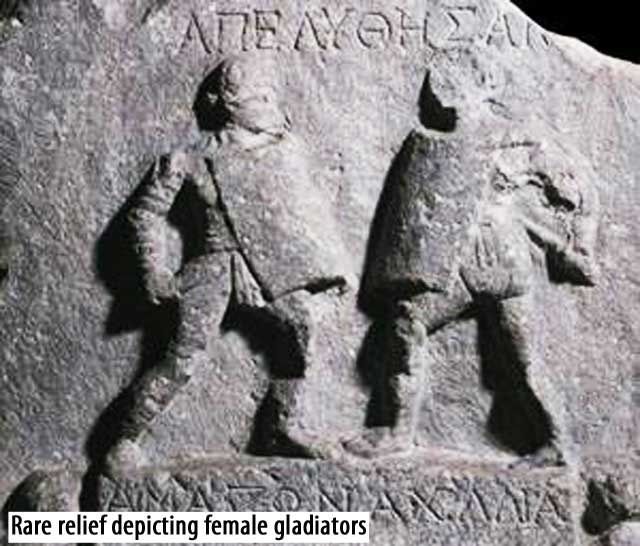

Women gladiators were known as gladiatrices or amazones, after the fierce tribe’s women of the Amazon. Just like their male counterparts, they were recruited from prisoners of war and slaves, but sometimes also wealthy Roman women fought in the arena. For much of the times of the Roman Empire women were considered weak, and needed to be under the control of their fathers or husbands. It is believed that their male guardians forced or encouraged their women to fight, in order to attract powerful Roman families to marry them.

Later, when women had some freedom, they may also have fought for thrills or excitement, although never for money because if they did it would have made them as low as common prostitutes or actors.

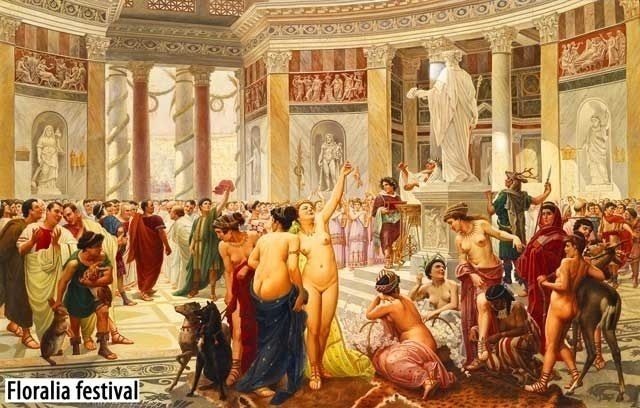

One of the best opportunities for women to be seen in the arena, and in the theaters of Rome, was a festival started by Julius Caesar, known as the Floralia. The festival honored Flora, the goddess of flowers, and included performances and plays by women, and games in the arena known as the Ludi Florales.

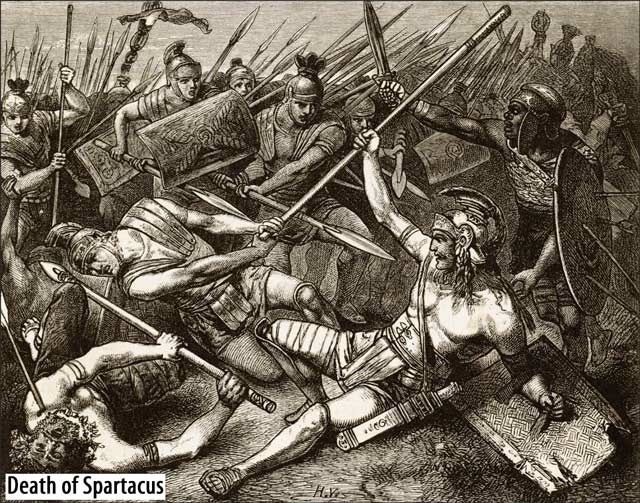

Spartacus was and probably still today is the most famous Roman gladiator, although he died 100 years before the Colosseum was built and obviously did not fight here. He rebelled against Romans and their love of cruel sports; he escaped and raised an army, fought proudly, but eventually, along with many of his army, was killed.

There were other famous gladiators too, for instance Flamma, from Syria, who died at the age of 30. In his life as a gladiator, he fought 34 times, won 21 of those fights, and was only defeated on 4 occasions.

And then, there were Priscus and Verus, the two gladiators who performed on the very first day of the opening games at the Colosseum, back then known as Amphitheatrum Flavium. Priscus was a slave born in Gaul, an area in western Europe, and Verus was a prisoner who worked as a stonemason in the Colosseum. Verus volunteered to become a gladiator because, as he saw it, it was the only way he could escape the terrible working and living conditions; the heat and dust were killing him, and he knew he would die, one way or another.

The two gladiators entered the ring to roars from the crowd, their shields and swords highly polished and glistening. The men bowed to their emperor and the fighting began.

Both men were equally matched, strong, young and agile, they moved quickly striking and ducking with accuracy.

The contest continued in this way for a long time, neither one of them able to get the upper hand until Verus lost his shield. The crowd gasped, was this the end? They had been taught well, and the rules of gladiator contests were known and adhered to by both of them - Priscus threw down his own shield.

Both men carried on fighting, but now they had no protection from their sword’s sharp edges, their arms and legs became slashed and bloody, then in an attack by Verus, Priscus lost his sword; he was defenseless. Surely, this was the end. But Verus threw down his sword, the crowd cheered, and the fight continued with fists until they were both near the end of their strength.

Never before had the crowd seen such a fight. The men were tired and could fight no more, and at the same instant, they both raised their hands to admit defeat. Now it was for the emperor to decide what should happen to them. For the first and last time in history Titus decided to declare both men victorious, he sent them wooden swords, the symbol of freedom, and palm branches, the symbol of victory. They were free.

There were other, rather surprising gladiators too. Some of Rome’s emperors also enjoyed showing off their skills in the arena. Emperors Titus and Hadrian were said to have either publicly or privately performed in the arena, but it was Emperor Commodus, a dishonorable, crude and cruel emperor who was the most renowned of all. Emperor Commodus engaged in all kinds of different gladiatorial contests, much to the dislike of the Senate and many of the plebeians. He thought himself to be the resurrection of Hercules, the god of war.

He dressed and fought as a secutor gladiator, heavily armored with a short sword, who fought against opponents known as retiarius gladiators who had only light armor, a net and a trident. He also fought as a bestiaries, or animal hunter, and this is one of the reasons he is remembered. On one occasion, he killed over 100 lions in one day, although he did this from a platform erected in the arena, so there was never much danger to himself.

On another occasion, and because he hated his senators so much, after killing an ostrich and cutting off its head he crossed the arena and held it up before the disgusted senators. Then he shook his head and wagged his finger; implying one of the senators could be next if they displeased him.

After this gossip raged around the city, it was said that the reason he was interested in acting as a gladiator was that his mother, Faustina the Younger, had an affair with the gladiator Martinaus, and from that affair Commodus was born.

It was not unusual for Roman women to fall in love with a gladiator, and perhaps the story of Faustina the Younger is true, and understandable. Gladiator’s appealed to women because of their strength and bravery; they were seen as real men, as apposed to, for instance, a boring senator. All over Rome walls were covered with graffiti like: “Caladus the Thracian makes the girls sigh” and “Crescens the net fighter holds the hearts of girls.” But it wasn’t just the women and girls who were attracted to the gladiators. The Syrian born emperor, Emperor Elagabalus, who became leader of the empire at the age of 15, also loved a gladiator.

Elagabalus became emperor in 218 and reigned for only four years under the name Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus, but in that time he had four wives and fell in love with a slave charioteer, Hierocles, declaring him his husband.

The story says that Hierocles fell in front of the emperor’s box, his long, blond hair tumbling from his helmet, and from that moment he became the emperor’s longest standing lover. But this kind of behavior was not appreciated by the masses, especially when the emperor declared, “I am delighted to be called the mistress, the wife, the Queen of Hierocles.” There were also other stories that, as a husband, Hierocles beat the emperor as any man would beat his wife.

Elagabalus’ lifestyle also brought and end to himself. He was captured by Roman soldiers, beheaded, and his body dragged through the streets before finally being thrown into the River Tiber. He was still only 18 years old.

Most gladiators only fought in two or three sessions each year, with each lasting between 10 and 15 minutes on average. Combats could be one on one, or a group of fighters in the arena together. Victors received a palm branch, the symbol of victory and an award from the sponsor, such as a crown, a gold coin, or a golden bowl. An impressive fighter would sometimes have the honor of a laurel crown and prize money. Gladiators who lived long enough to die a natural death were buried in segregated cemeteries away from Roman citizens, their bodies said to be impure.

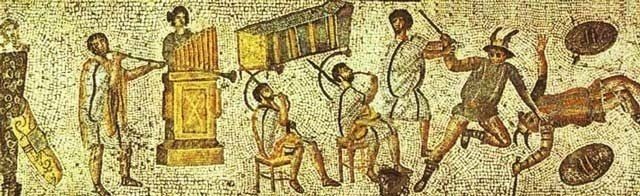

Just like today, details of forthcoming events would be advertised on notice boards giving details of the sponsor, date, the reason for the games, and the number of gladiator fights that would take place. There were also details of other highlights such as executions, music, facilities and free gifts that spectators would receive. These included the use of the sunshade, water sprinklers, food, drink, and sweets.

The night before an event the gladiators enjoyed a feast with family and friends; this was to be a symbolic last meal for some of them.

On the day of the event, a comprehensive program was available for those who could read. Even some of the plebeians and poorest citizens of Rome could read and write, with the richer families having their children educated with private tutors, or sent abroad to Greece to study. The program showed details of the gladiators, how many fighting sessions they had won, how many they had lost and their area of specialty. This information was used to determine betting odds, and those spectators with enough money could place bets on the result of each fight.

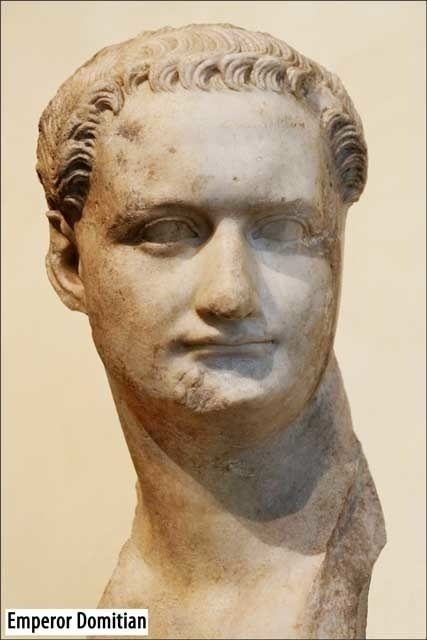

The last of the Flavian emperors, Domitian, liked to spice up his events and in particular he enjoyed games, which involved torch-lit fights between dwarves and women. These fights were part of the main act with bare-chested women fighting without helmets and many without armor.

The Roman people loved their games, even those who hated bloodshed found the atmosphere electric. The emperors knew that providing exciting entertainment for the people was an excellent way to stay popular, and so the Colosseum continued to delight for many centuries, but it also had its fair share of unfortune.

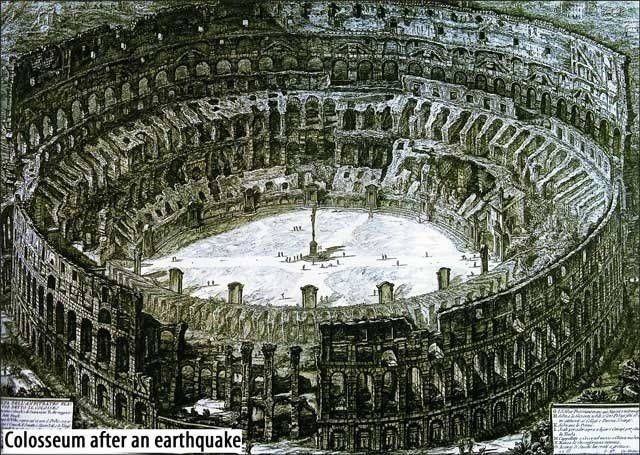

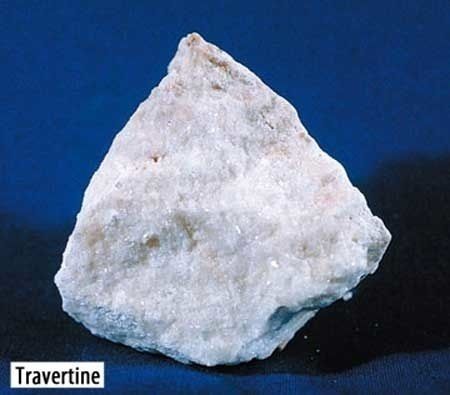

In 217, a lightening storm struck the heart of Rome. The fourth floor of the Colosseum, which was largely constructed from wood, was hit by lightening and the entire top floor was destroyed by fire. The fire also burnt and blackened a large area of the lower levels so badly that the brick and travertine, in the area to the right of the northern entrance, had to be replaced, and the arena was not fully functional again until 240.

Despite this and other unfortunate tragedies, use of the Colosseum continued for many years afterwards, but in the end, the novelty of murder, animal slaughter and fighting dwarfs became monotonous; the people wanted other types of entertainment. By year 435, the last of the gladiator contests was fought, and in the following 100 years, the animal hunts were also finished. From this point, the Colosseum went into decline; it was left abandoned to the homeless, animals and wild flowers.

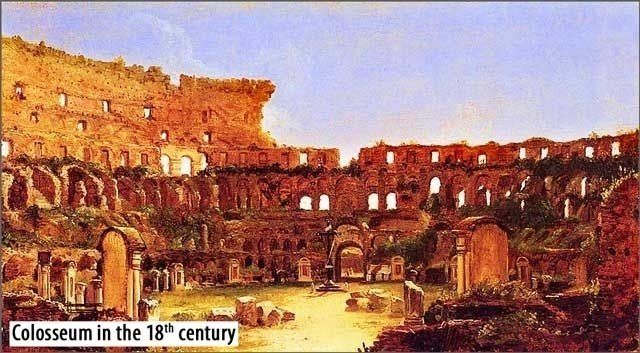

The Colosseum also suffered severe damage from a great number of earthquakes; the largest in 1362, that caused the south side of the outer wall to collapse. Huge piles of rubble, brick and travertine lay on the ground, but not for long. Citizens took advantage of the ‘free’ building material, which had suddenly become available, and soon pieces of the Colosseum were being taken to decorate private homes. However, it wasn’t just the citizens who took materials, the rulers of Rome also allowed materials to be taken and used to build roads, bridges and houses; Palazzo Venezia and the Ponte Sisto bridge were two such constructions.

In the 16th century, an amusing idea came from the enterprising pope, Pope Sixtus V. He had the idea of turning the Colosseum into a wool factory to provide alternative employment for Rome’s prostitutes.

By the 18th century, there was very little stone left to be taken from the site, and protection of what remained took over. The last surviving remnant of the outer wall on the north side was reinforced with two brick supports, which added strength to what remained.

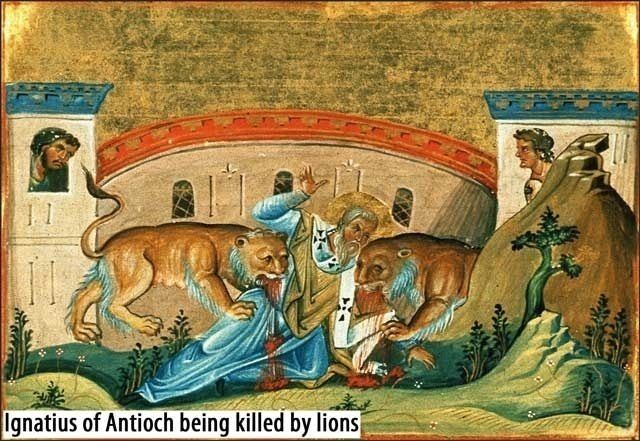

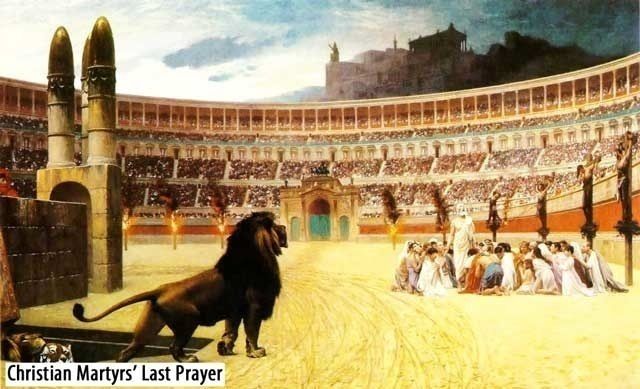

But it were not just the Romans who were interested in the Colosseum; from the 6th century the Church became involved in all matters concerning the mighty building. On some occasions, the Colosseum had been used as the site for the public executions of Christian martyrs.

For instance Ignatius of Antioch was killed and eaten by lions here. This is why Christian leaders wanted to make the Colosseum sacred. After the building had been abandoned by the Romans, religious orders used the space to establish a small church and used the land as a cemetery; the vaulted area under the arena was used as workshops and housing.

The cross stands here as a remembrance of those times.

On the outer wall is a plaque dedicated to Pope Benedict XIV who was responsible for declaring the Colosseum a national monument in 1749 and therefore saved it from ruin. He was also the one who installed the big cross and fourteen others, which have been removed.

Today the religious connection still continues with the Pope starting a Good Friday procession and mass from the site.

The Colosseum is the symbol of Rome, the center of the Roman Empire and of course one of the city’s top places to visit. During its lifetime it has seen mighty rulers come and go; it has also seen death and violence.

Today, it is not excited Romans who visit for beast hunts and gladiatorial contests, but visitors of a different kind, like us, who come here to witness the remains of an incredible building and try to recreate an image of what happened here in its heyday.

The Colosseum certainly is an impressive symbol. However, it was not the first, or the largest stadium to be built here in Rome, that honor fell to the Circus Maximus, a mostly wooden construction five times the size of the Colosseum.

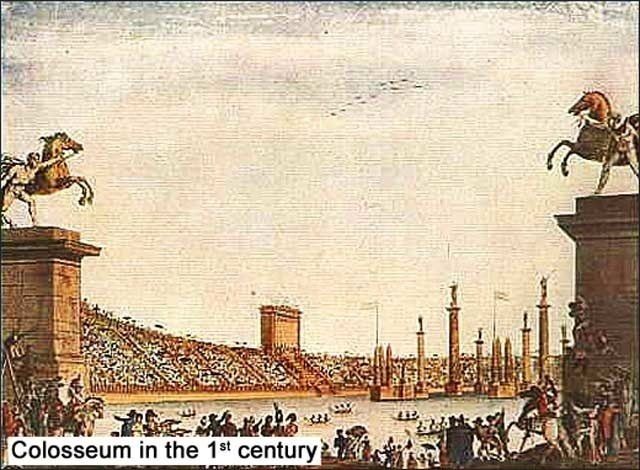

But, despite there already being one vast arena, which held chariot races and gladiator events, Emperor Vespasian started work on a new amphitheater, in 70.

This was to be a permanent structure not one made of wood, a magnificent oval auditorium, 189 meters long, 153 meters wide and 48 meters high. This was to be an amphitheater covered with over 100,000 cubic meters of travertine, which in turn was held in place by 300 tons of iron clamps.

Travertine was, and still is, used as a substitute for marble. It can be used, as it is in the Colosseum, as a thick tile to cover brick, just like tiling a bathroom, it can be used to carve statues, or it can be used in blocks to build arches, steps or even whole buildings.

It is a white or cream limestone created by volcanic springs found between Rome and Tivoli to the east, and could be polished to produce a shiny finish, to give the same effect as marble or left unpolished to look like limestone.

Nine years into the project, in 79, Emperor Vespasian died, and his son Titus became emperor.

At that time, the Colosseum already had three floors and was almost complete; all that Emperor Titus needed to do was to add the fourth and final floor. He did this within the first year of his reign, so in less than ten years the arena was finished.

Gleaming and new, it was named the Amphitheatrum Flavium, after the family name of the emperor responsible for its construction, Emperor Vespasian, and his sons Titus and Domitian.

The mighty Amphitheatrum Flavium opened its doors for the first time with an extravagant celebration lasting for 100 days. In true Roman style, this was the first of many spectacular events involving gladiators, exotic animals, musicians, and performing oddities, such as people with small heads, large bodies or the obese.

The stadium was packed with 50,000 spectators all dressed in their finest togas, there were senators and noblemen, foreign dignitaries and citizens of standing.

Further away from the arena, on the upper floors were the plebeians, or ordinary citizens of Rome, and finally the plebeian women and slaves, who would watch the games from a distance.

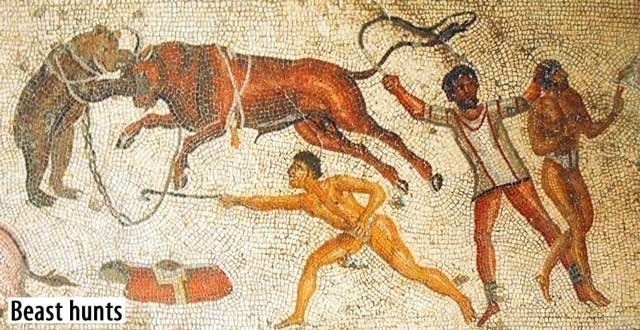

Excitement filled the air. The expectation was high at the thought of elaborate events, which included hunts with animals imported from Africa known as venatio, a word in Latin meaning a “hunting game”, or chase.

There were strange looking creatures with long necks, others with strong, muscled bodies and aggressive roars, and some with sharp teeth that were found in rivers. To the plebeians these were mythical creatures from faraway lands.

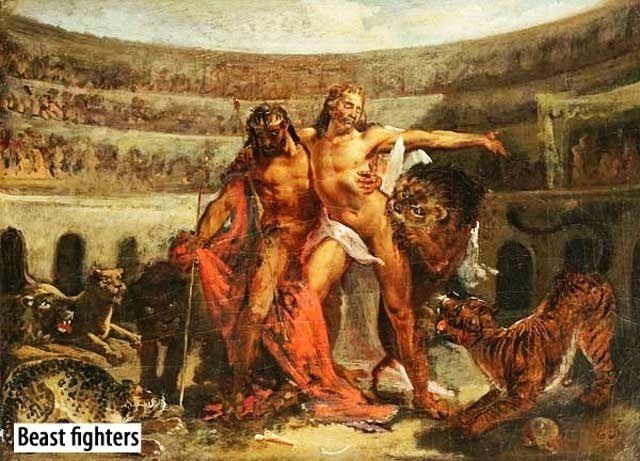

The animal hunters were gladiators trained at the scholae bestiarum; one such school was close to the Colosseum, known as the Ludus Matutinus.

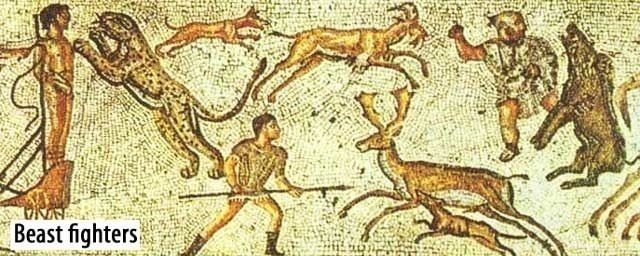

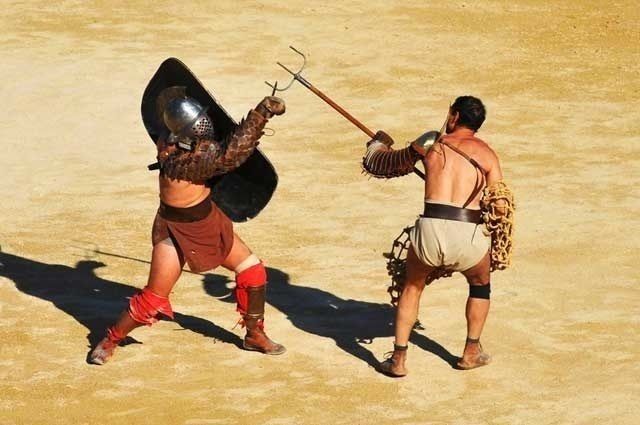

They were special gladiators known as secutores, or “chasers”, retiarius, or “net fighters”, and bestiarii, or “beast fighters”.

These gladiators resembled barbarians armed with spears, knives and sometimes whips. Their arms and legs were wrapped in leather straps, they wore canvas loincloths, helmets with visors and a decorative crest on top; sometimes they also wore sandals on their feet.

Although fighting beasts such as tigers, lions and other large beasts may sound dangerous, many gladiators volunteered to become beast hunters, as it was less dangerous than other forms of fighting which often included a fight to the death.

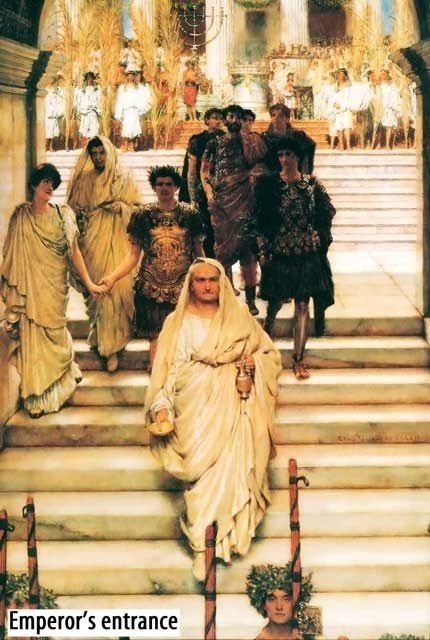

All the events were different, but the most elaborate started with the entrance of the emperor dressed in his finest robes. The crowd roared; they knew that this spectacular was to be one of the best, their host was generous, and no expense would be spared for their enjoyment.

After the emperor’s grand entrance came a procession of slaves carrying images of both the emperor and the gods who were there to protect and entertain. There was Diana the god of hunting, Jupiter the king of all the gods, Charon the ferryman to hell - in Roman times known as Hades, Bacchus, the god of wine, and Apollo, the god of poetry, tales, and music.

Next came the trumpeters playing fanfares and a scribe to record the events of the day, and then, the games could truly begin.

First there were informal, warm up sessions of fighting with unsharpened instruments. Then comedy fights between dwarves, but this was just a prelude of things to come.

Then came the beast hunts. Animals were pitted against gladiators who were trained on how to perform a daring show, where they appeared to take great risks and prove themselves to be brave, without actually causing too much danger to themselves.

Some of the animals were left unharmed and allowed to leave the arena to fight another day, others were not so lucky. In one event, it was recorded that 5,000 beasts were killed in just one day.

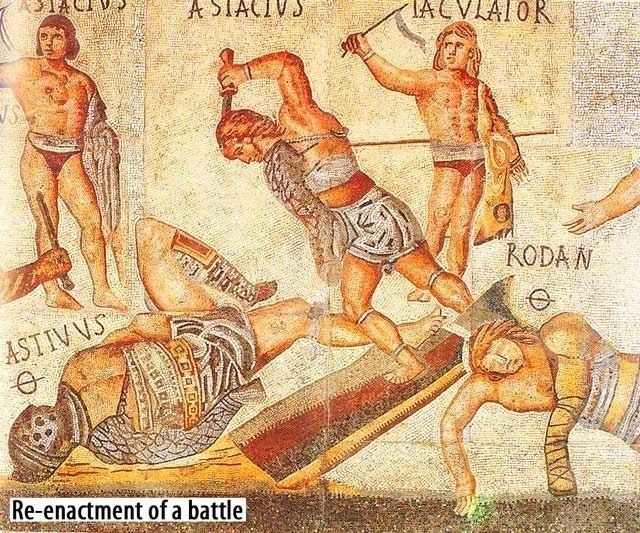

Next came the re-enactments, which were accounts of actual battles fought and won by the Roman legions, as well as mythological battles from Greek and Roman stories. The battles were gruesome, true to life and death as many of the actors lost their lives just as the Roman soldiers had done in the real battles.

Usually the minor and most dangerous parts were played by slaves, criminals and undesirable people dressed in military uniform, with the lead roles of Greek soldiers and Thracian soldiers, who fought with spears, being taken by gladiators.

Many battles were re-enacted, but two of the most popular were the battles between the Syracusans and the Athenians, and the battle of the Roman army against Hannibal, which also involved elephants.

During some events executions also took place. The executions, which were also held in other arenas throughout the city, were of criminals, army deserters, traitors, runaway slaves and Christians, who were said to be guilty of antisocial behavior because they worshiped only one god. The Romans worshiped many gods, just as the Greeks had done. The Romans sought out the Christians, persecuting and crucifying them just like their leader Jesus and his followers, and on some occasions, the Colosseum was used as the site for their public executions.

These executions were inspired by mythology and included being burned to death, being nailed on a cross, stoning, or being eaten alive by beasts, which was known as damnatio ad bestia.

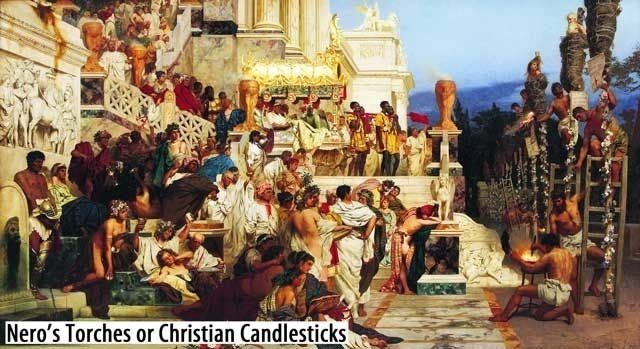

The worst and most cruel emperor, Emperor Nero, nailed his most hated victims, the Christians, to a cross and burned them alive to act as torches at dusk to light the arena.

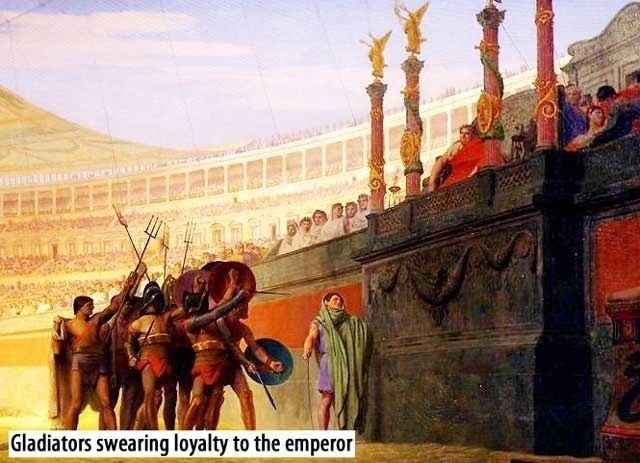

The excitement would begin to grow even further with the entrance of the gladiators. They paraded around the arena in their extravagant purple and gold cloaks and lined up to swear loyalty to the emperor, “Hail Emperor! We men who are about to die salute thee.” This was the final and most extravagant part of the ceremony.

The gladiators marched off to wait their turn to fight, and when they re-entered the ring, they did so to a fanfare of trumpets and cheers from the crowd. They wore their finest armor adorned with feathers, precious stones and covered with expensive metals, their slaves carrying large highly decorated swords, which were a demonstration of both the gladiators’ wealth and power.

There would be special bouts of fighting involving left handed gladiators who fought right-handed opponents. In between the matches, during the interval, musicians would entertain the crowds who would also enjoy gifts of food and wine offered by the sponsor of the event.

Not all the games in the Colosseum were sponsored by the emperor; anyone with enough money to put on a spectacle was encouraged to do so. Many of Rome’s richest citizens were the senators. They believed that the more money they spent on providing the best games, the more votes they would receive at election time, so an incredible amount of effort was put into creating memorable events, throughout the year, that the plebeians would appreciate.

This was known as panem et circenses, which translates to “bread and circuses”. They were the words used to describe the way of influencing power over the Roman people by offing them pleasures such as bread and entertainment, keeping them quiet and peaceful, but at the same time giving them the opportunity to voice themselves in these places of performance.

This was especially true of Julius Caesar, although this was before the Colosseum was built. He was famous for organizing magnificent games, and borrowing lots of money to pay for them. But, because the people believed he had done it for them, he got their votes, and he was able to pay back everything he owed; other emperors followed this example.

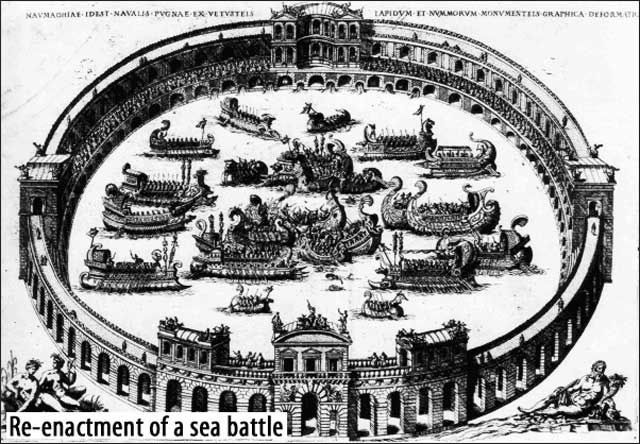

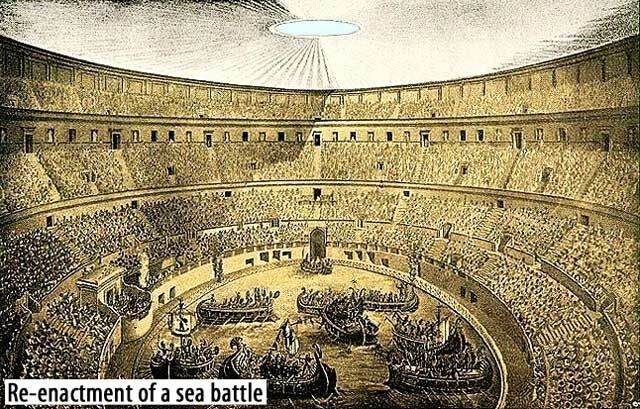

During each of the annual events or celebrations, different games and matches were held. In addition to the animal hunts and grand fights of the gladiators, there were sylvae, or recreations of natural scenes with real plants and animals from around the world. Many naumachiae, or sea battles, were re-enacted on lakes within the city, but the Colosseum was also used as a venue for such events.

During the 100 days of celebrations, Titus filled the arena with water and brought in bulls, horses and domestic animals who had been taught to swim. He also staged a sea battle, which replicated the battle between Corcyreans and Corinthians.

It is believed that, because of its size, the Colosseum could only reproduce small battles or battles where ships were made to scale rather than full size versions.

But how did the Amphitheatrum Flavium become known as the Colosseum? This dates back to long before the Colosseum was even built. Following the great fire of Rome in 64, the emperor of the day, Emperor Nero, confiscated large amounts of his citizen’s private land and claimed it for himself.

On some of this land, in the center of the city, he built a magnificent palace called the Domus Aurea, also known as the Golden House. In its grounds, he built aqueducts to channel water to a series of gardens with artificial lakes and pavilions, and in one garden he also built a statue, the Colossus of Nero. The Colossus was 35 meters high with a face modeled on Nero and the body of Helios, the sun god.

The Flavian family inherited these confiscated lands, but unlike Nero, they were compassionate towards their people and wanted to restore their land back to them. But, as well as being compassionate, they also wanted to celebrate the grand victory of their battle in Jerusalem, so the gardens and lake were laid flat, and the Amphitheatrum Flavium, an amphitheater for the people, was constructed.

But the name was yet to be changed to the Colosseum. In the 8th century a monk, Venerable Bede, made a statement in Latin, “Quamdiu stat Colisaeus, stat et Roma; quando cadet colisaeus, cadet et Roma; quando cadet Roma, cadet et mundus.” This translates to, “as long as the Colossus stands, so shall Rome; when the Colossus falls, Rome shall fall; when Rome falls, so falls the world.”

Venerable Bede was talking about the statue, the Colossus, but over the years, the name was transposed to the Colosseum and by the year 1000 the statue had fallen, Rome was still strong, and the name Colosseum had stuck to the amphitheater.

Traditional Turkish handicrafts

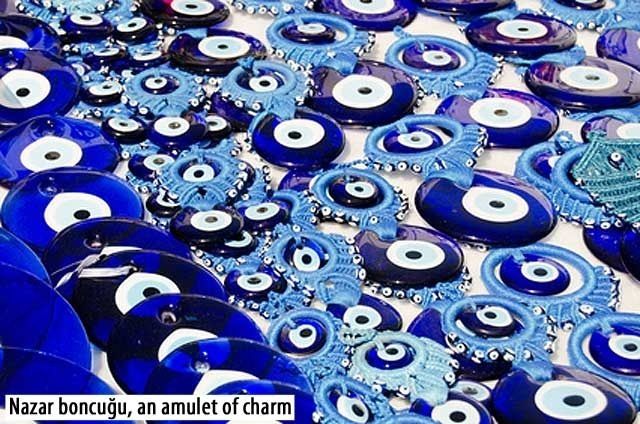

While in Istanbul, you will no doubt see and be tempted to buy many beautiful trinkets to bring home with you as a souvenir. The storefronts in bazaars are packed with different colors, textures, and smells, each piece competing for the attention of your eyes. There are soft scarves, shining gemstones and cut glass (who knows which is which?), incense, tea, Turkish delights. And nazar boncuğu, an amulet of charm, which supposedly protects the wearer from the evil eye, and hopefully watches out for you, because you are unsure if anyone else will.

However, some of these souvenirs are more culturally Turkish than others. In this story, we will describe several different Turkish arts and handicrafts that are exemplary of Turkish culture. These are Turkish carpets and kilims, tiles, miniatures, calligraphy, and ebru - the marbled paper.

Hopefully you will find something that piques your curiosity. Have no fear, there are many treasures to discover in the bazaars and backstreets of Istanbul.

Carpets and Kilims

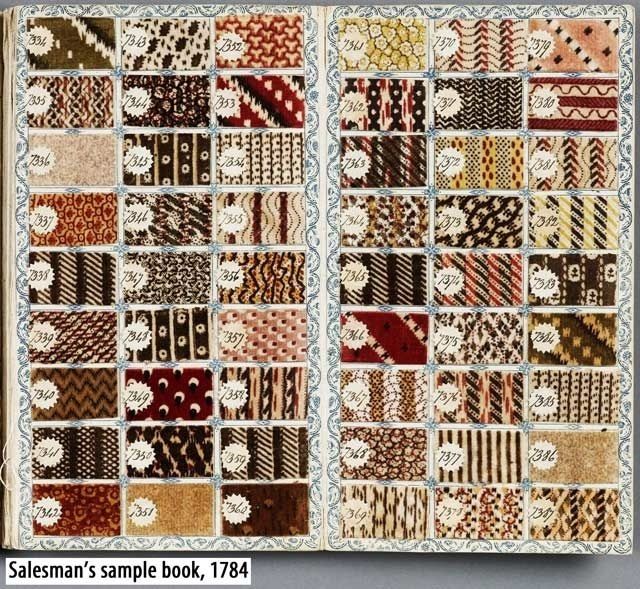

Turkish carpets and kilims are not only one of the preeminent crafts of the Turks, but also of Turkic people in general.

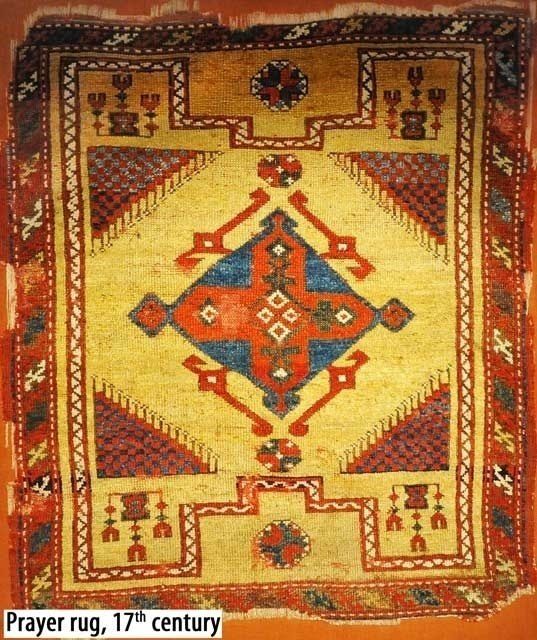

Kilims and carpets are different from one another in that kilims are flat woven while carpets are thicker and involve many knots, and are technically known as knotted-pile carpets. Although there are motifs and techniques associated with Turkic kilims that are unique, this general category of weaving was not new to the world, and existed in a number of different cultures at the same time.

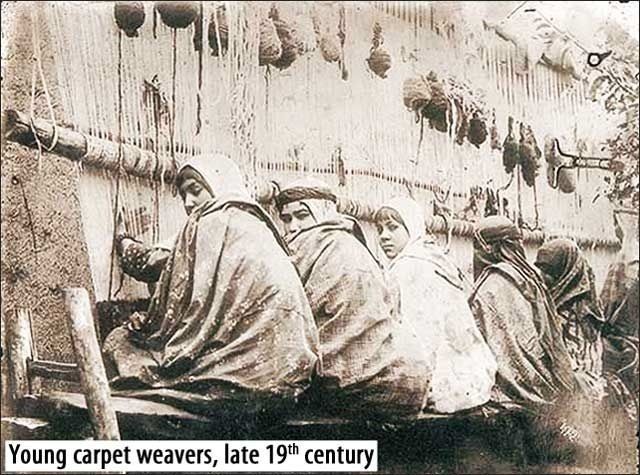

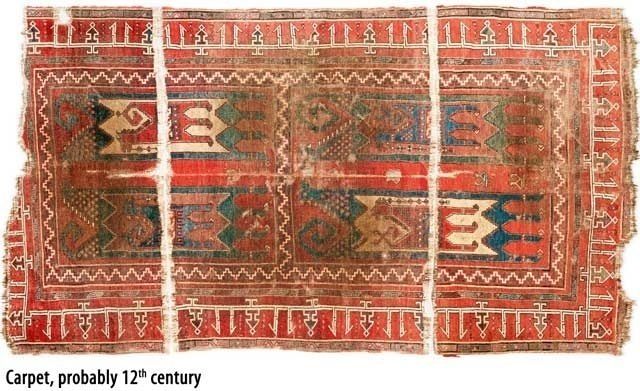

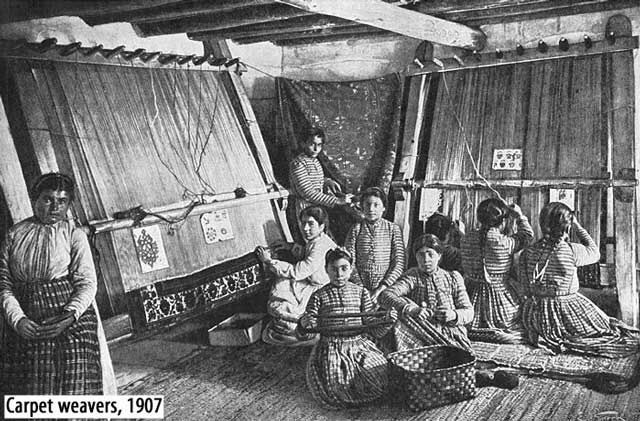

However, many scholars have suggested that the art of knotted-pile carpet weaving originated in Central Asia with the Turkic people, and was brought to the Middle East by the Seljuks sometime in the 11th or 12th century, the Seljuk Empire being a predecessor to the Ottoman Empire. The people who made the carpets were overwhelmingly women, and they would weave them for use in their own homes. The weaving of kilims and carpets even from a very early period was not only for utilitarian purposes; with all their beautiful and meaningful patterns and the colorful dyes, kilims and carpets are also certainly an art form.

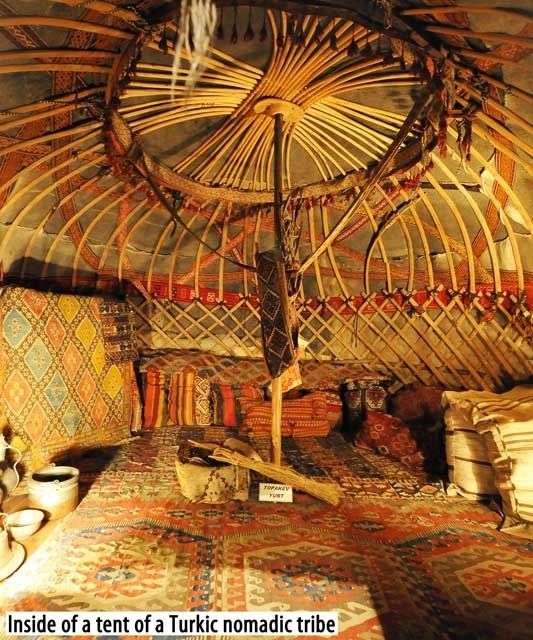

Kilims were especially important to the Turkic nomadic tribes because they were easy to make, fold, and transport. They have also been made by ancient peoples for much longer than knotted-pile carpets. They are known by slightly different names depending upon where they were made, such as cicim, sili, or zili. Generally, kilims are easier to make than many knotted-pile carpets, but some are made from thin strings of yarn and are remarkably detailed. Kilims almost always display bold geometric designs, sometimes with animals such as birds or phoenixes.

Knotted-pile carpets are more difficult to make than kilims, and were accorded a higher value in society.

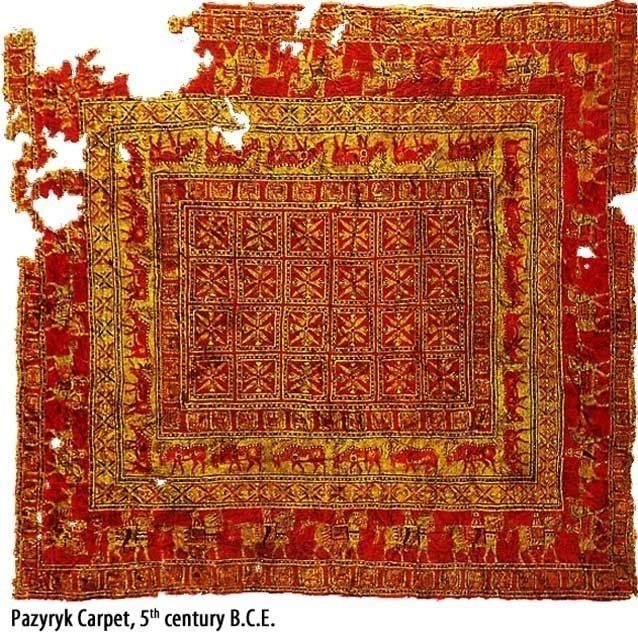

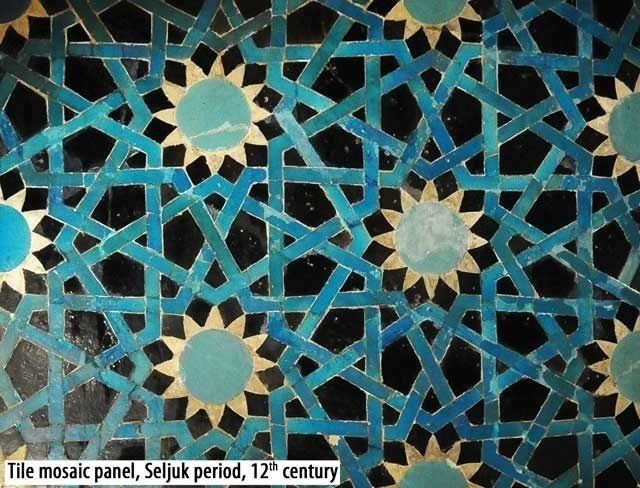

The earliest example of a knotted-pile carpet dates from the 5th century B.C.E. and is known as the Pazyryk Carpet. After this, not very much is known about the earliest examples of Turkic carpets since not many have survived. Instead, the history of the carpet becomes clearer during the Seljuk period, in the 13th century, when these carpets were used to decorate the inside of Seljuk mosques.

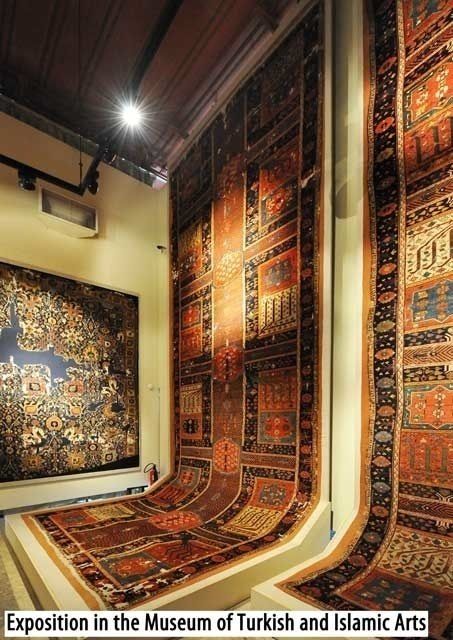

Many of these very old carpets can be seen in museums in Istanbul, such as the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts.

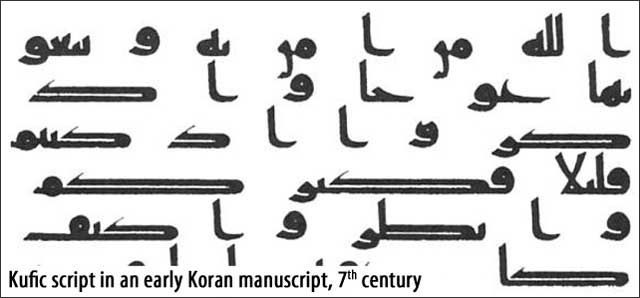

Seljuk carpets are known for their use of geometric shapes, and the border around the edge of the rug, which is often filled with the Kufic form of Arabic calligraphy.

Turkish carpets produced during the next several centuries after the Seljuks are categorized using their appearance in Western paintings. This is because when a wealthy merchant or nobleman in the West would commission his portrait to be painted, he would arrange the signs of his wealth around him to be included in the painting. In this way, anyone who looked at the painting would see at a glance that the man depicted was wealthy. Usually it was a man, but of course women also had such paintings commissioned. One of these signs of wealth was carpets.

Because the time period of the painting was known, along with the identity of the owner of the carpets, and perhaps even where the carpet was purchased, the incredibly detailed paintings helped to determine the history of Turkish carpets when they were matched with other carpets discovered around Anatolia. For example, scholars have concluded that the 14th century was when animal motifs began to appear in Turkish carpets due to the appearance of carpets with animal motifs in European paintings from that century.

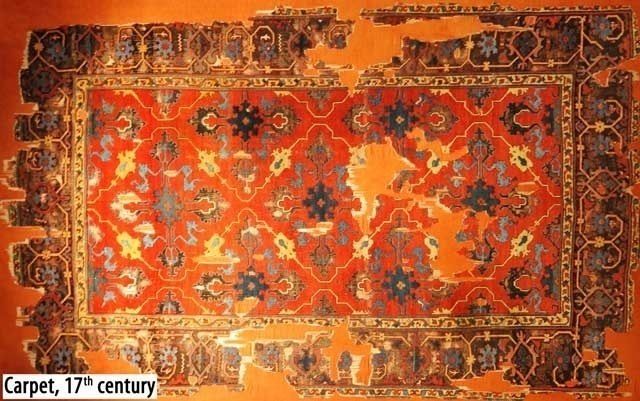

The Ottomans began to take over Anatolia and make their own carpets in the 14th century, but the 16th century was when Ottoman carpets began to take on a style of their own. Before this, they closely resembled Seljuk carpets. For one, in the Ottoman period, the animal motifs began to disappear and were replaced with more floral elements.

The height of Ottoman carpet weaving can be said to be in the 16th and 17th centuries. However, carpet weaving continued to develop well into the 18th and even 19th century.

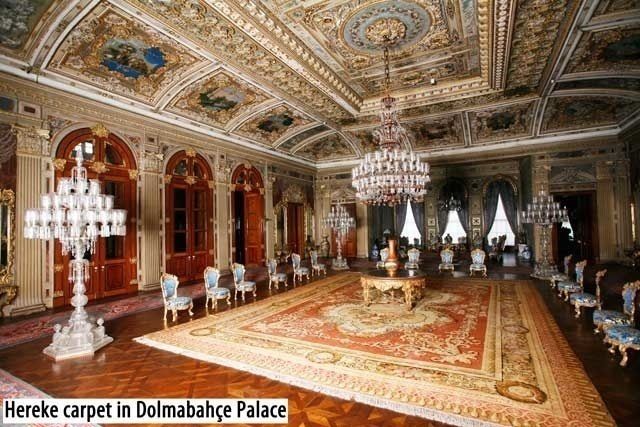

In 1891, the first carpet factory was opened by Sultan Abdülhamid II in Hereke, where many of the carpets you can see in Dolmabahçe Palace and other Ottoman palaces were woven.

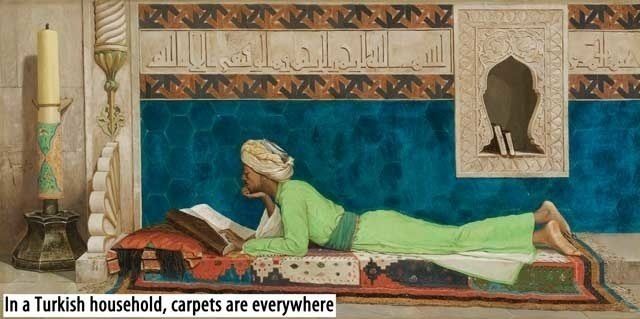

Carpets have, through centuries, had their natural place in all Ottoman and Turkish households as well as in mosques.

In the 20th century, however, the traditional art of carpet and kilim weaving began to decline when carpet-weaving machines were introduced, which then took the place of weavers. Despite the fact that they are increasingly hard to find, hand-woven, traditional carpets are still made in many regions of Anatolia.

However, the liveliness and innovation in this field has significantly diminished. Sadly, many consider kilim and carpet weaving to be a dying art form.

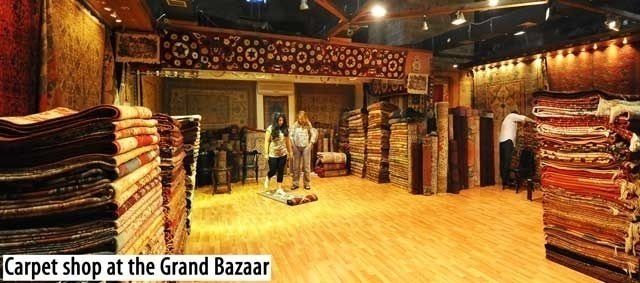

As for buying carpets in Turkey today, it doesn’t have to be an incredibly complicated or confusing transaction. The most important part of this process is finding a reliable carpet dealer.

The Grand Bazaar or Sultanahmet area are not the worst places to shop for carpets, and most tourists will be able to find a carpet seller they can trust in this area. In this case, if you are alone, knowing a few tips and tricks may help you understand what you are buying. Carpets made by hand are of course more expensive than carpets made by a machine. If the carpet at all smells like a machine or machine oil, it has undoubtedly been made by a machine, no matter what the carpet seller says.

A good quality carpet or kilim will have small, strong knots, or a small weave, that will not shed any material when they are pulled on. Turn the carpet over on its back: if you can distinctly make out the pattern on this side, and if you notice the knots being small and similarly sized, then it is probably well made.

The material of the carpet will affect the price as well. While most carpets are made out of dyed wool, the most expensive ones are made from silk.

Very high-quality carpets will be dyed with natural dyes, but be careful, because it is extremely difficult to tell a natural dye from an artificial dye. It is safe to assume that most carpets sold today have been dyed artificially, but this does not mean that they are ugly or worthless.

If you are looking for an antique carpet, or a carpet from a specific area, such as for instance Hereke, the price will increase again. Be aware that there are many tricks that are used to falsely ‘antique’ a carpet, such as putting it into a hut with goats for a month.

Of course, the complexities of carpet buying increase with the amount of money you want to spend. Therefore, if you are looking to purchase an antique or very expensive carpet, consulting a professional or a professional book is necessary. In any case, bargaining is part of the process of buying a carpet – just be sure to keep the bargaining process positive and lighthearted.

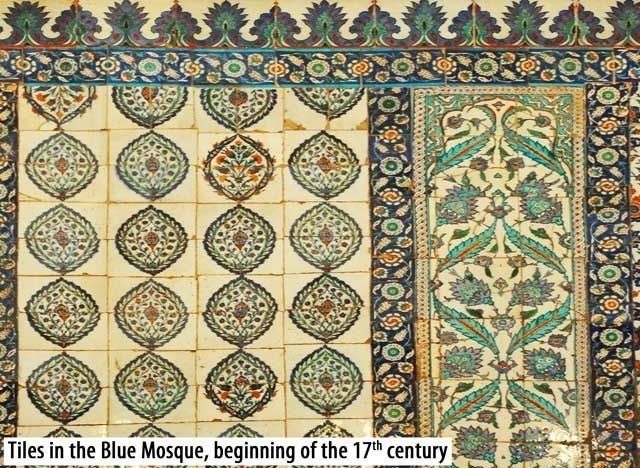

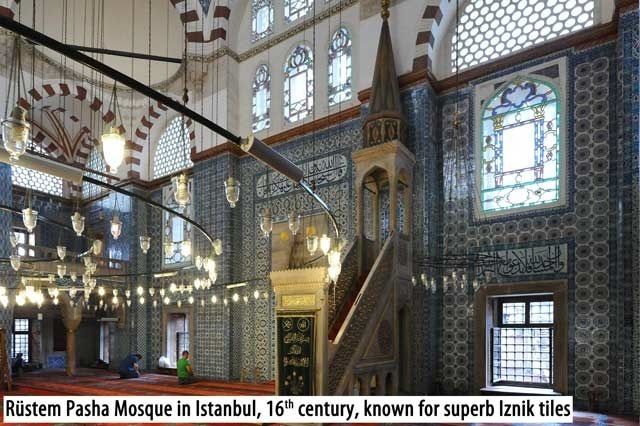

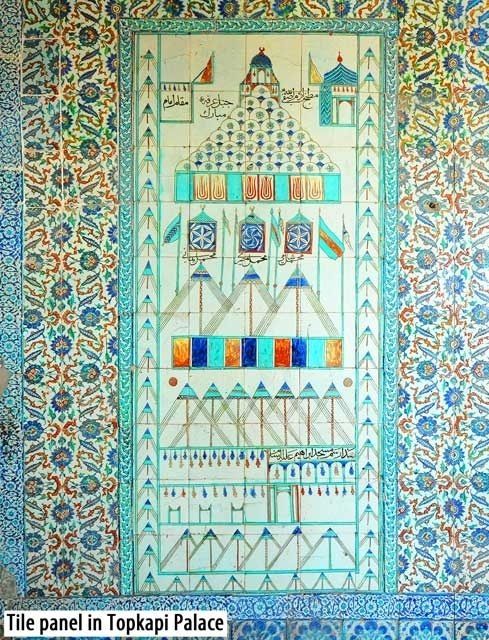

Tiles

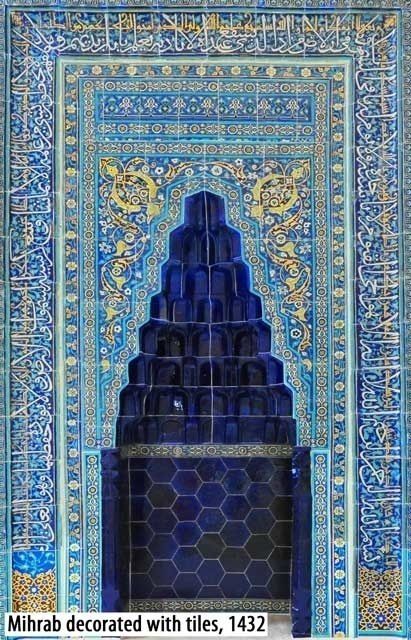

Turkish tiles are another very old art form that has its roots in the more utilitarian craft of pottery making. The Ottomans were undoubtedly influenced by the Seljuks’ use of tiles to decorate the exterior and interior of buildings, and developed their own tiles early on, before the conquest of Constantinople in 1453.

Tiles during this period were generally of one tone, often with the tiles themselves being different shapes. Gold leaf was sometimes applied to these tiles to add some design.

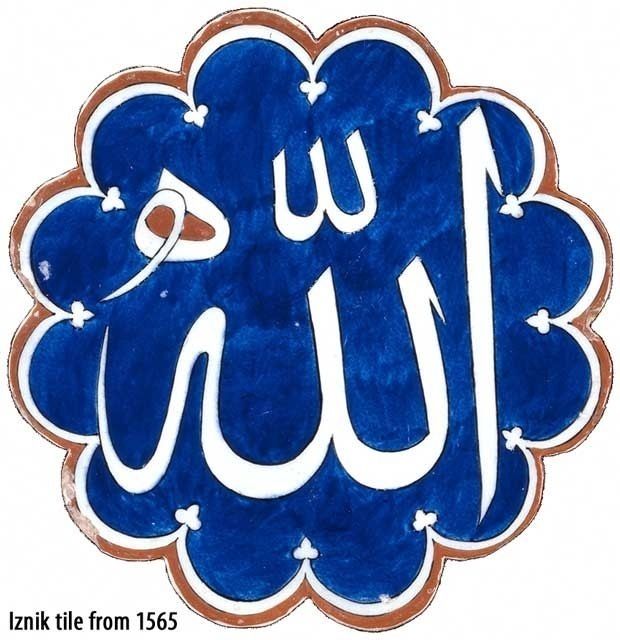

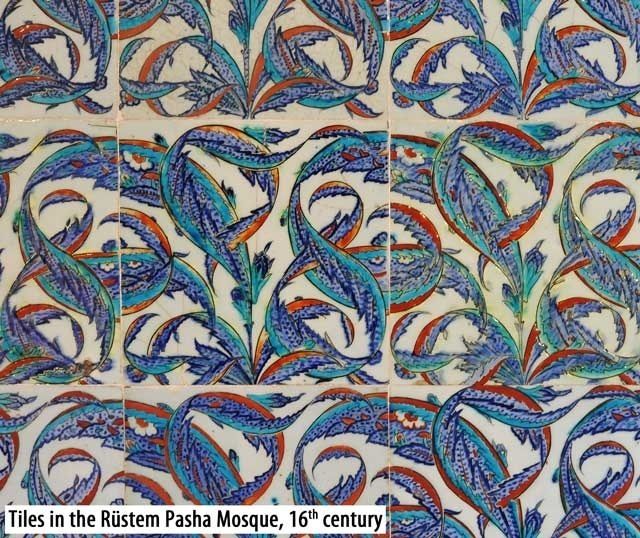

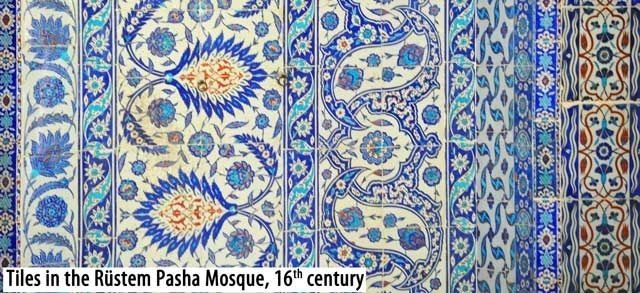

Tile making and pottery in general in the Ottoman Empire was highly influenced by that of the Chinese. One can certainly see the influences of Chinese pottery especially in the choices of patterns - chrysanthemums, swirling cloud-like figures, and colors - blue and white. However, no one can disagree that the Ottoman tile makers still found a way to express their own unique motifs, especially as the practice matured. But this took time, as did the development of the full array of colors in Iznik tiles.

First, only a dark cobalt blue was used in the designs; next, turquoise was introduced, then a soft green and a dark violet, which were soon replaced, in the middle of the 15th century, with the characteristic bright red, sometimes called bole red, and a vivid green.

The real innovation began in the late 15th century, when tile makers were able to achieve a solid white background upon which to base their other designs. And at the end of the 15th century, all of these colors could be used in the same piece.

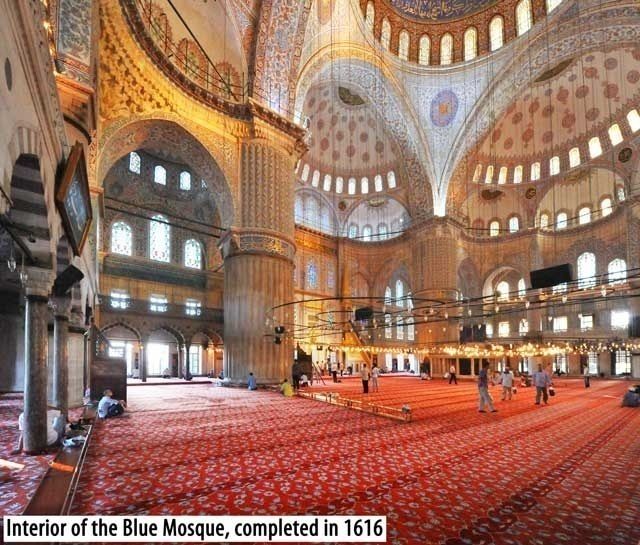

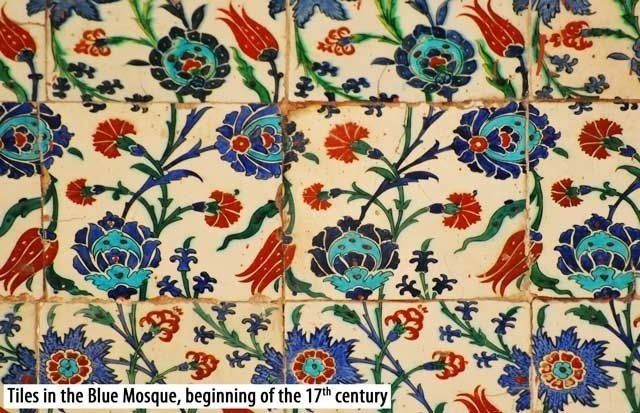

But it wasn’t until the 16th century that we see intricate designs on tiles made from glazes. The tiles during this period were usually just squares; the emphasis was upon the amazingly detailed designs drawn upon the tiles.

The city of Iznik (historically known as Nicaea) developed as the center of the tile-making industry, and was supported in part by the Ottoman sultans and other royalty who paid the tile makers large sums of money to create magnificent tiles for the palaces and imperial mosques.

In the mid-16th century, the Ottomans discovered how to create a deep red color, which was highly valued and rare, and is especially indicative of Iznik tiles of the highest quality. This color was extremely difficult to make, and craftsmen were able to achieve a consistent result only during the high period of Iznik tile production.

However, during the second half of the 16th century, Iznik tile production drastically deteriorated for a number of different reasons.

For one, the Ottoman Empire itself had begun its slow decline, and for another, pottery prices were kept artificially low by the government, thereby depreciating their worth and lowering standards. So it happened that by the early 17th century the unique quality and craftsmanship shown in the tile industry had faded.

Then, by the mid-17th century, the decline in the quality of the tiles was quite apparent. Most noticeably, it was during this century that the secret of making the rich red color was lost.

Strangely enough, but sometime in the 18th century all of the production secrets of the beautiful Iznik tiles were lost. Since instructions had never been written down in a record that survived the years, this cultural heritage disappeared after production quality declined to such an extent that there was no question the tiles being made were of a totally different nature from Iznik tiles. For hundreds of years, no more high-quality Iznik tiles were produced in Turkey.

Then, in the 1990s, Prof. Işıl Akbaygil decided to find the reason why some Ottoman mosque’s tiles were in good condition despite their age and others were not. This inquiry led her to rediscover and also revive the lost art of Iznik tile production. In 1993, she established a foundation called the Iznik Training and Education Foundation dedicated to the preservation of this historical art form, and to the production of Iznik tiles of the highest quality. Also to ensure that the secret of the fabulous Iznik tiles would never again be lost! They now produce quality Iznik tiles for the general public, the Turkish government, and for use in restorations.

There are a number of places in Istanbul, and throughout Turkey, which sell tiles utilizing patterns and motifs from the Iznik tiles; however, not all of these are created equally. The Iznik tiles that were produced during the 16th century are qualitatively different from many of the cheaper and less durable tiles and pottery sold in many souvenir shops today. Quality Iznik tiles simply feel heavier because they are not made from only clay or porcelain, but also contain quartz. In fact, Iznik-style tiles are up to 90% quartz.

The way in which the tiles are produced is quite interesting in itself. The material used to first form the shape is clay mixed with very finely ground quartz and glass. This was a technique used so that the piece could be fired at lower temperatures. One can feel that real Iznik tiles are much heavier than regular terracotta or porcelain. Because this initial mixture differs so much from normal clay, the pottery cannot be shaped on a pottery wheel and instead must be formed using molds. After the form is dry, a white under-glaze is poured on.

Then, a design is sketched onto a piece of paper, and tiny holes are made in the design. This is then laid over the tile, and a fine mist of charcoal dust is applied, so that it comes through the holes and the design can be seen on the tile. Next, the design is painted in different colors, fired in a furnace, and then a clear, shiny glaze is applied, giving the tile its smooth feel and shiny appearance.

All in all, it is a process that cannot be completed by any single individual, in a timely manner, at least. Therefore, true Iznik pottery pieces rarely have a single artist’s signature anywhere upon the piece.

Authentic Iznik tiles are still produced in this way, but they are much more expensive and harder to find than their lighter, cheaper alternatives.

It is easy to buy tiles or other ceramics in Istanbul around the Sultanahmet area, in the Spice Bazaar, or in the Grand Bazaar, and they range from very cheap to quite expensive. Even the high-quality quartz tiles can be found.

Simply shopping around for a good deal and then looking for the best quality work and something that appeals to you is all that’s required. Just be careful: some of the glazes used still contain lead, and should not be used for eating or drinking. Usually, if you can see a clean, white glaze underneath the designs, they are fine. If you are worried, do not use the plates for eating hot food.

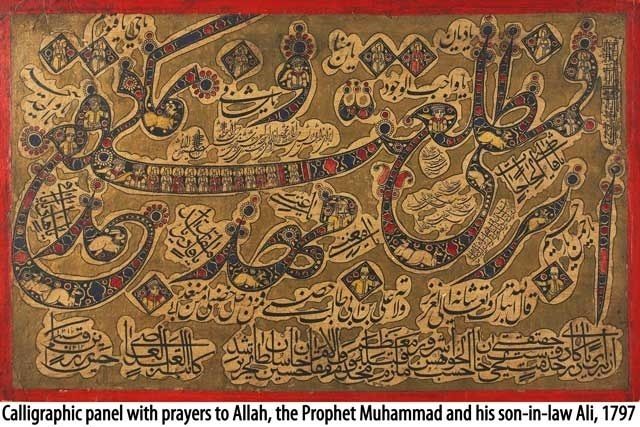

Calligraphy

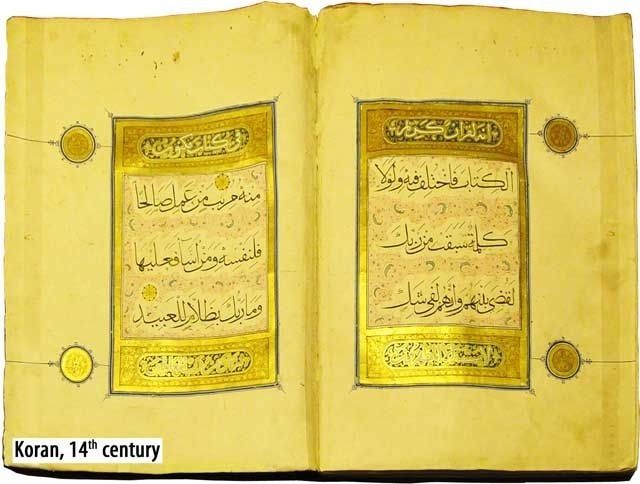

Calligraphy is perhaps the oldest and most celebrated art form of Islam. It is also the art form which best unites all the other arts in Islam. For example, calligraphy can be found on carpets, tiles, fabrics, gold and silver objects, and in miniatures and architecture. Probably the reason for calligraphy’s importance in the Islamic world comes from the importance of copying the Koran, and the Islamic restrictions regarding the depiction of figures of animals and humans in art. In fact, in the ancient world of Islam, one learned how to read and write, and found the importance in reading and writing, from the Koran and other religious texts. Therefore, the act of writing has always held a prominent place in Islam.

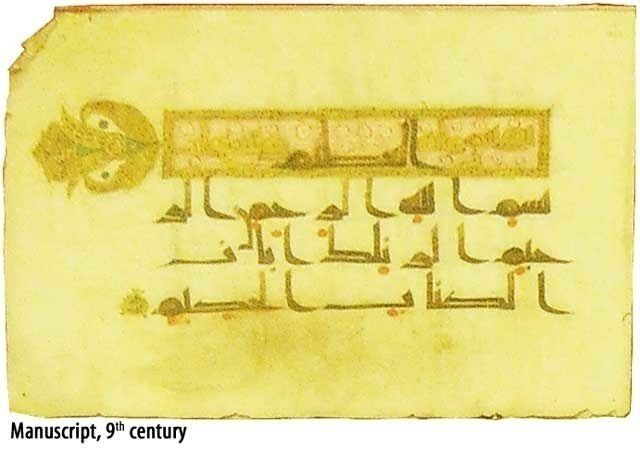

Some say that the art of calligraphy started in the early 7th century with Ali, who was the cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad. Since that time, different styles of calligraphy have appeared throughout the history of Islam in different areas and different time periods.

The first calligraphy style that was used to copy the Koran was the Kufic style, which is easily recognizable for its large characters and geometric, block-like script.

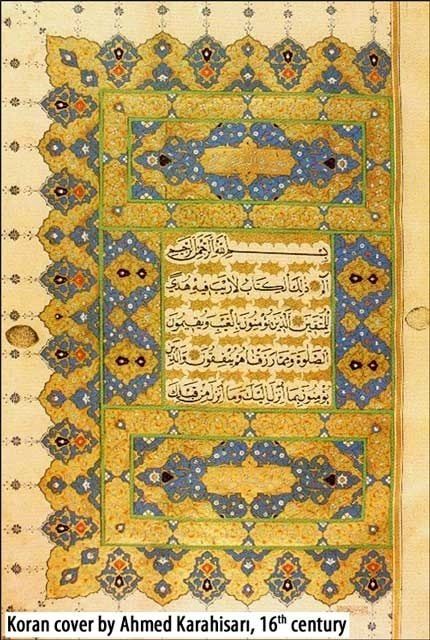

Later, many other different styles were invented, such as Thuluth, Naskh, Rīḥānī, Muḥaqqaq, Tawqi, and Riqaa, which were created during the Abbasid period around the 10th century, but these are more difficult to distinguish from one another if one is not familiar with Islamic calligraphy. One of the most influential Ottoman calligraphers was Ahmed Karahisarı, who lived and created beautiful calligraphic pieces during the 16th century.

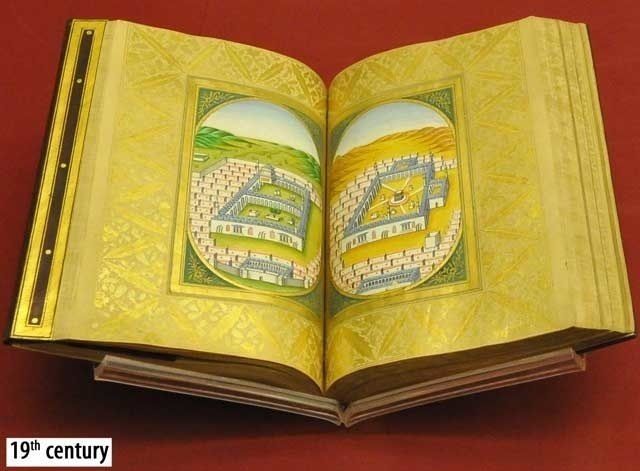

Although calligraphers had the practical task of creating enough Korans for there to be one in every Muslim home, they were doing far more than simply copying words. The Koran, which held the words of Allah as received by the Prophet Muhammad, was so revered that it could not be treated as any simple, ordinary object.

Each Koran was, indeed, a work of art. The pages were sometimes dyed shades of blue, pink, or brown, and often calligraphy was accompanied by the small drawings called illuminations or miniatures.

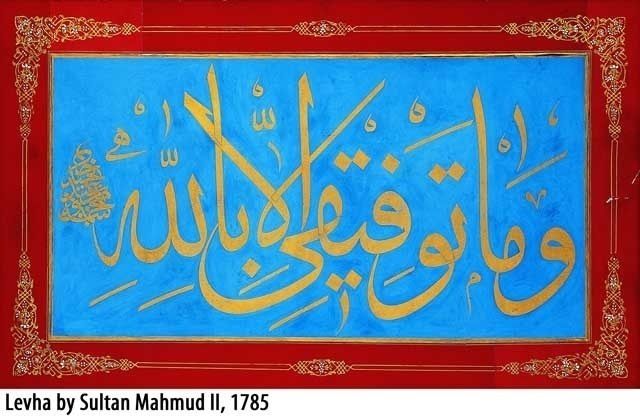

Pages containing verses from the Koran or other religious texts could combine calligraphy and miniatures, and then be framed and hung on a wall, in which case they were called levha.

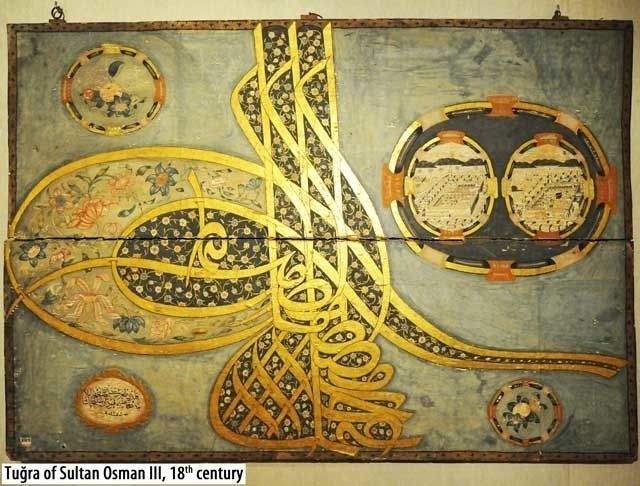

Tuğra, or official emblem or signature of the sultan, was also done in calligraphy, often with small painted additional design elements.

Calligraphy’s importance began to wane when the printing press was brought into the Ottoman Empire in the 18th century.

Then, when the Latin alphabet was adopted by the Republic of Turkey in the 20th century, Turkish calligraphy using Arabic script lost its importance almost entirely.

It is now only practiced by a few people in specialized organizations who are dedicated to preserving the art of calligraphy in Turkey. Therefore, while calligraphy is surely a part of Turkey’s cultural heritage, it is no longer a part of daily life.

With this said, calligraphy pieces are something nice to bring home from Istanbul. Often there are artisans around the Sultanahmet area who will write your name in calligraphy on a ceramic plate or dish – however, this is an entirely new development mostly geared towards tourists, and they also usually write in English.

In the Grand Bazaar, you can find some nice levha and other such items, and although they can make a very nice souvenir they are almost undoubtedly mass-produced.

If you want to find high-quality calligraphy, hand painted by a contemporary master, contacting an organization like Nakkaş Tezyini Sanatlar Merkezi is a good idea. Of course, purchasing a piece of calligraphy from such an organization will be like purchasing a work of contemporary art, so be prepared for much, much higher prices than what you will find in the bazaars.

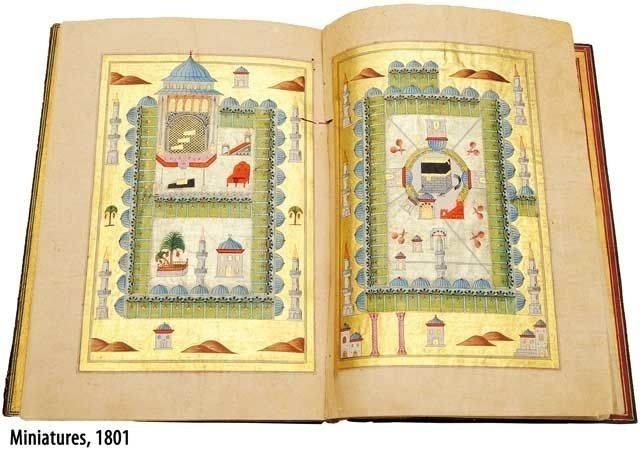

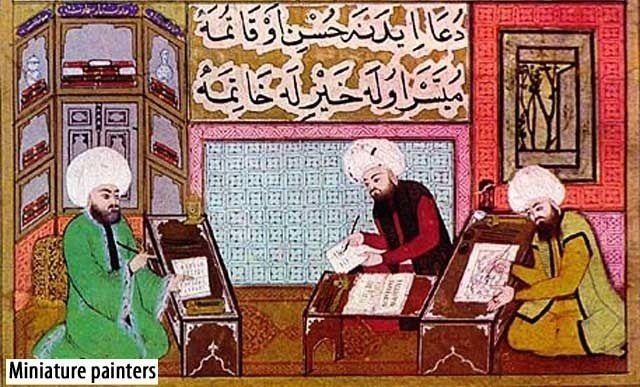

Miniatures

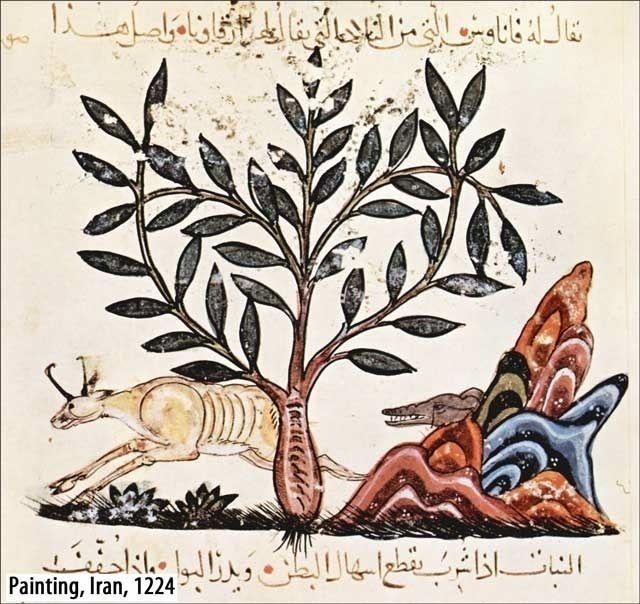

Cultures without the tradition of miniatures do not understand the importance of this art form. Technically speaking, miniatures are small paintings of plants, animals, people, or designs that are part of a book. In the West, miniatures are not considered paintings and are of a lesser art form. But for many cultures of the East, miniatures are highly valued and an extremely important part of their artistic traditions.

Miniatures began as a complement to calligraphy, an older and more valued form of art in the Islamic world. Turkish miniatures began to appear in Central Asia from around the 8th century. The Seljuks developed the art of miniatures further and certainly influenced Ottoman miniatures. However, Ottoman miniatures developed a distinct style and tradition separate from what had come before. One way in which they accomplished this was that they began to depict scenes that were faithful to the Ottoman world, such as Ottoman architecture and clothing styles. As simple as this may seem, it was different from the highly regulated, standardized art, which had come before it.

Probably you are familiar with Islam’s dislike, and sometimes even hatred, of the artistic depiction of people and animals, and so the concept of miniatures is confusing to you. Interestingly enough, it seems that in many of the Islamic empires, the palaces of powerful and wealthy individuals often supported figurative art in paintings and frescoes, and even displayed them on their walls. Indeed, such paintings could at one time even be found inside Topkapi Palace.

However, this is not to say that it was permissible everywhere, or that the Islamic ban on figurative art is a myth. It is simply that different people during different time periods had a more moderate interpretation of the Islamic ban of figural depictions. For some, this ban only related to sculpture. Sculpture was still avoided by every Muslim, and is not something that can be found in classical Ottoman art.

Furthermore, it is necessary to note that Ottoman miniatures have an entirely different aesthetic and purpose than Western paintings. For one, Eastern miniatures in general did not seek to display the realistic emotional or psychological lives of the painted subject. Realism was pursued only so far as it did not cross this line. In this way, although miniatures of a particular person could resemble them, they did not try explore and express the inner life of the person. Instead, they sought to depict ideal characteristics, such as beauty or bravery.

It was also necessary to keep the figures two-dimensional, so as not to make them too lifelike. This style is entirely different from traditional Western-style painting, and this is also why many of the Ottoman miniatures may seem boring or lifeless to someone not familiar with the different goal of miniatures.

At any rate, figurative art could never be found inside mosques, of course, and the normal Ottoman subject would not have had enough money to employ a miniature artist or buy such an art object.

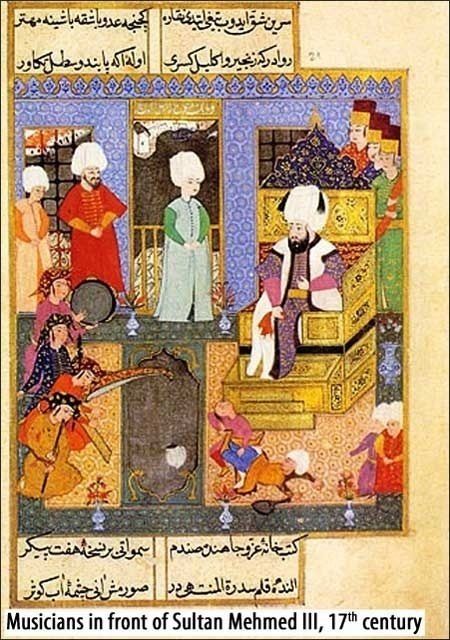

For this and other reasons, the art of miniature painting was limited to the guilds of miniature painters, which were sponsored by the Ottoman royalty and other wealthy individuals – and even within this, some time periods and sultans were more moderate than others were.

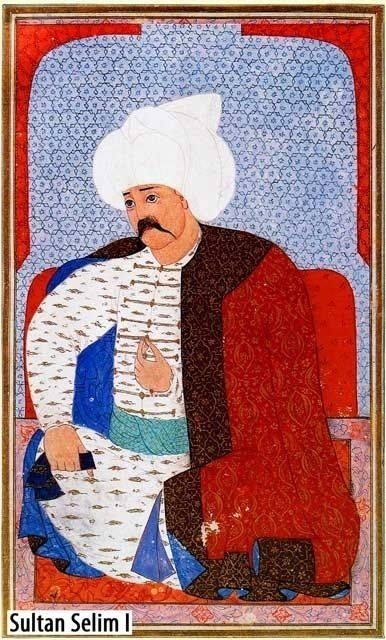

Because of this, the examples that we have of Ottoman miniatures revolve around the lives of the Ottoman royalty and other wealthy individuals. Some portraits have even survived, especially of the Ottoman sultans.

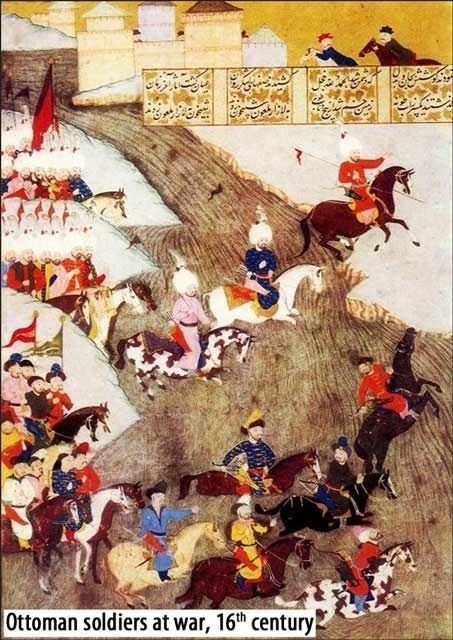

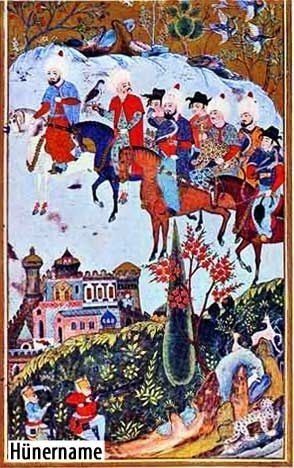

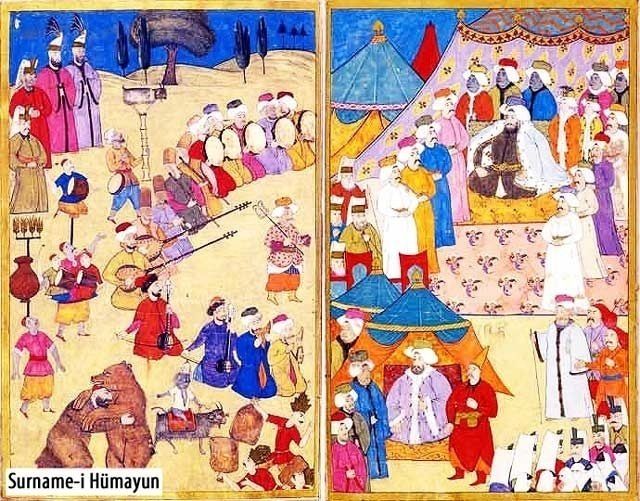

The most famous examples of Ottoman miniatures detail war expeditions, such as “Hünername” or “The Book of Accomplishments”.

But also festivals, such as “Surname-i Hümayun” or “The Book of Imperial Festivals”, which describes in words and depicts on miniatures the festival dedicated to a long circumcision ceremony during which Murad III’s son Prince Mehmed was circumcised in the late 16th century.

The miniatures became increasingly more realistic and therefore influenced by the West, during the later periods of the Ottoman Empire.

Eventually, however, the art of miniature painting was overshadowed by the influence of Western painting, and then finally the camera.

Today the art of miniature painting still exists in Turkey thanks to different foundations, which keep the art alive, as well as individual artists who have mastered the skill. This differs from the art of miniatures during Ottoman times, when individual artists were usually not emphasized, and certainly no single artist would sign the finished work as it was more of a collaborative effort.

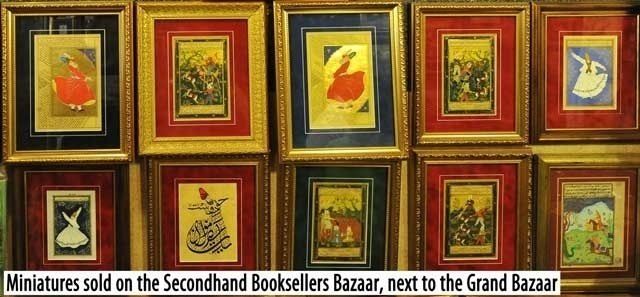

Just like calligraphy, lesser examples of miniatures are prevalent throughout the Sultanahmet area and in the bazaars and can be purchased rather inexpensively. On the other hand, if you want to buy a contemporary miniature, it will again be similar to buying a contemporary work of art, and you will pay accordingly. Miniature artists study for years and years, even decades, before they can be considered masters, and so it is reasonable that the prices for their work are quite high.

The courtyard of the Little Hagia Sophia has many beautiful examples for sale, and the Nakkaş organization also carries stunning miniatures, but not all of them may be for sale.

Ebru

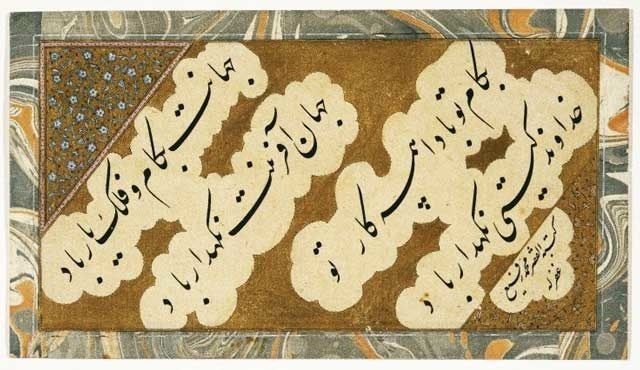

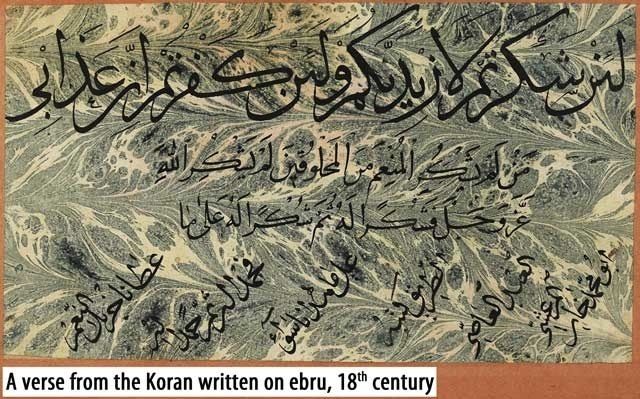

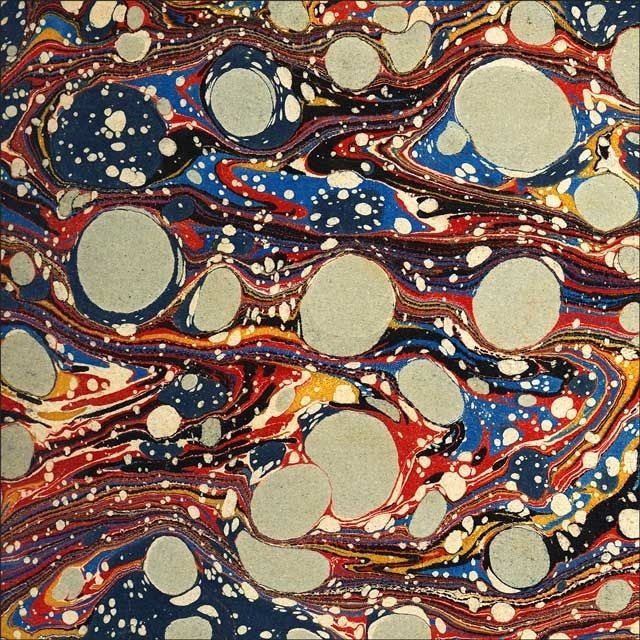

Ebru is the art of paper marbling. Unlike the other art forms we have discussed so far, ebru has been much less influenced by Islam, most likely because it is usually not involved with either figures or words. Paper marbling creates a pattern on paper, which is similar to the patterns that can be found on marble.

It is a technique that is found all over the world, and it is difficult to pinpoint the time period in which it began. However we know that it moved into the Ottoman territories from the Far East, by way of Persia, around the 13th century. As is the case with miniatures, an ebru artist would not sign his work. Sometimes, calligraphy would then be drawn on the ebru paper.

Interestingly enough, ebru paper was also used by Ottoman sultans for official documents. It was thought that since ebru was a highly refined art, it would be very difficult to forge such an item.

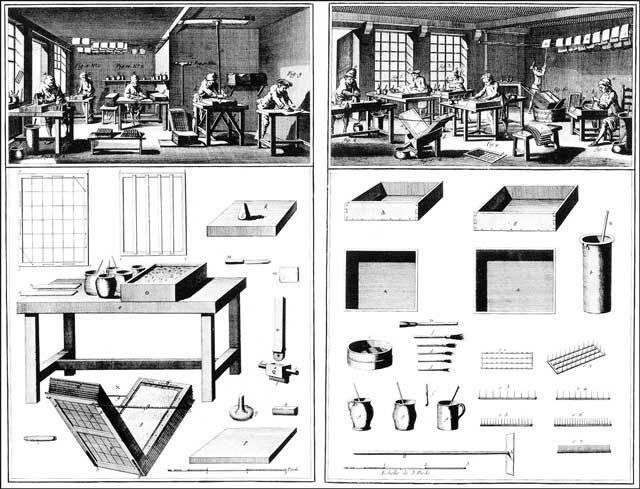

The process of making ebru is particularly interesting. First, a rectangular basin, the size of whatever paper the ebru will be printed upon, is filled with a mixture of water and gum tragacanth, which is a substance that is acquired from the roots of a plant native to Turkey. This mixture makes the water viscous.

Natural dyes are then prepared by mixing a colorful powder, usually made from a mineral oxide, with water. Another special substance, made from ox bile – a substance that is produced in the liver of an ox, is then added to the dyes, which prevents them from sinking in the water.

The ebru artist then uses a brush to flick dots of dye over the surface of the water, and then manipulates them with a series of different tools to create curves, waves, and spirals of colors.

Sometimes during this process, a very skilled ebru artist can also draw pictures of, say, whirling dervishes or flowers. When the artist is finished, he takes a thick paper and carefully lays it over the surface of the water. After the paper sets for a short period of time, it is removed from the basin and hung to dry.

Master ebru artists spent a lifetime mastering different techniques that would be sought-after both in the Ottoman Empire and in Europe.

Ebru is certainly still practiced today and is one of the more popular traditional Turkish arts.

It is quite easy to come across examples of ebru in the Sultanahmet area and beyond. However, there seem to be not so many ebru masters around as compared to Ottoman Empire times.

The travel magazine that SHOWS you around and tells STORIES, not just history.

Do you like to travel? But perhaps you don’t always have time. Even so you still might be curious about how people lived in those faraway palaces and castles, or maybe you just want to understand more about different cultures? Well, we have exactly what you need – the WanderStories travel magazine, where we tell WanderStories™.

WanderStories™ e-magazine Armchair Travel Guide tells you fascinating stories behind the history of interesting and famous sights in the cities around the world. In fact, we do it so well that you can visit the most extraordinary places around the world without even leaving the comfort of your armchair.

WanderStories™ travel magazine is unique because our storytelling style puts you alongside the best local guide who tells you fascinating stories, while a wealth of high quality photos brings your tour vividly to life.

You will get to know how real people, emperors and sultans, concubines and eunuchs, slaves and executioners, lived in the palaces you will visit; what gods the monks worshipped in these temples; how generals and soldiers, crusaders and gladiators, fought and won, … or died. You will learn about local traditions and customs, holidays and festivals, cuisine, even jokes.

Our promise: when you read the WanderStories travel magazine in the comfort of your armchair you will feel as if you are actually visiting the best sights in the city with the best local guide.

Please subscribe to the WanderStories travel e-magazine Armchair Travel Guide at: wanderstories.com/travel-magazine

Please buy the Kindle, iPad/iPhone or PDF versions or this and previous issues of Armchair Travel Guide at: wanderstories.com/travel-magazine-buy

Please get WanderStories travel guides at: wanderstories.com

Armchair Travel Guide

WanderStories™ travel magazine

Issue: 1, 2014

Copyright © 2014 WanderStories

Photos by WanderPhotos™

ISSN 2228-3870

All rights reserved. No part of this magazine may be reproduced or distributed in any form by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems without permission in writing from the publisher.

Disclaimer. Although the authors and publisher have made every effort to provide up-to-date and accurate information and have taken all reasonable care in preparing these publications they accept no responsibility for loss, injury or inconvenience sustained by any person relying on or using our publications and make no warranty about the accuracy or completeness of their content and, to the maximum extent permitted, disclaim all liability arising from their use.